2.5 Applying the Communication Process

Our goal as communicators is to use our understanding of the communication process to make sure that when we send a message, the circle of our Context of Production overlaps as much as possible with the audience’s Context of Use.

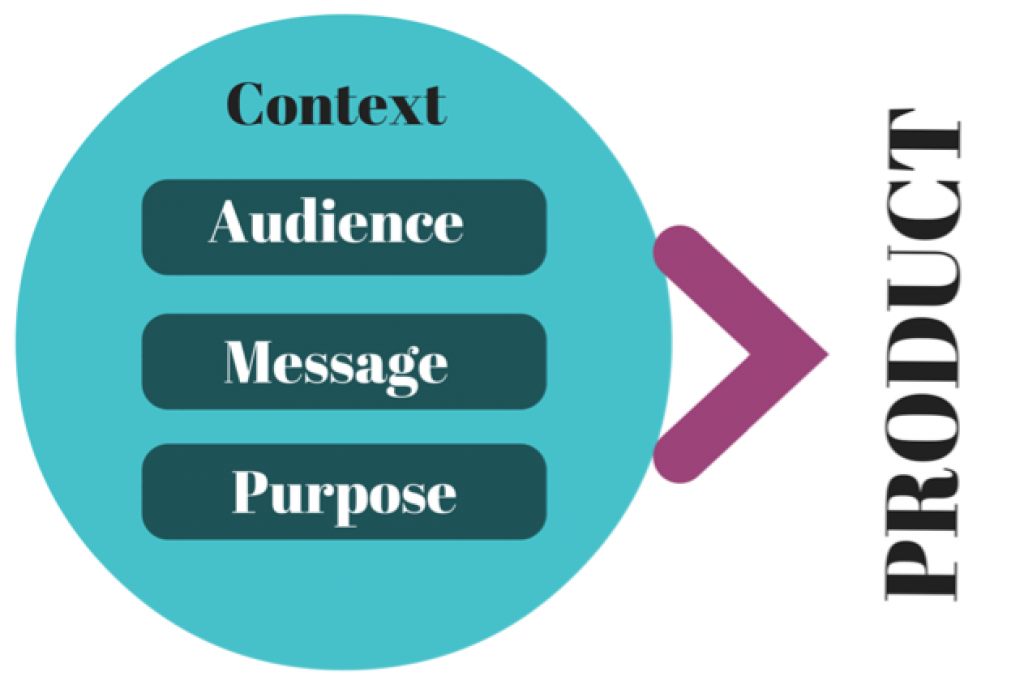

Another way to look at the communications process is to think of CMAPP, which stands for Context, Message, Audience and Purpose. The context is the situations that impact communication. The message is what people say, and the audience is the person or group involved in the communication. The reason for communicating is the purpose, and the product is the form of communication.

To communicate effectively, you should undertake the following steps.

1) Determine the Message’s Purpose

In their book The Essentials of Technical Communication, Elizabeth Tebeaux and Sam Dragga (2014) note that in the workplace, you “write to create change.” By this, they mean that every piece of communication done in the workplace has some sort of purpose. You don’t send an email or write a proposal just for fun. You write to change something. Maybe you want to change something small, like having your coworker send you a file, or maybe you want to make a big change, like convincing another company to buy goods or services from you. But every piece of writing in the workplace should exist for a reason.

Before you can start communicating, you need to know the purpose of the message. What do you want your audience to do? Sometimes, the purpose is obvious. If you’re applying for a grant, for example, the purpose is to win the grant and earn the money. Sometimes, however, the purpose is not so clear. Let’s say that you receive an angry email from a customer. Depending on your relationship to the customer and the nature of their complaint, you may respond with the purpose of keeping the customer’s business, you may respond to break bad news in a way that the audience will at least respect, or you may not respond at all.

2) Analyze your Audience

The audience any piece of writing is the intended or potential reader or readers. This should be the most important consideration in planning, writing, and reviewing a document. You “adapt” your writing to meet the needs, interests, and background of the readers who will be reading your writing.

The principle seems absurdly simple and obvious. It’s much the same as telling someone, “Talk so the person in front of you can understand what you’re saying.” It’s like saying, “Don’t talk rocket science to your six-year-old.” Do we need a course in that? Doesn’t seem like it. But, in fact, lack of audience analysis and adaptation is one of the root causes of most of the problems you find in business documents.

Audiences, regardless of category, must also be analyzed in terms of characteristics such as the following:

- Background—knowledge, experience, training: One of your most important concerns is just how much knowledge, experience, or training you can expect in your readers. Often, business communicators are asked to be clear, but what’s clear to you might not be clear to someone else. For example, imagine that you’re a software developer who’s developing an app for a client. Unfortunately, your code had a number of bugs, which put you behind schedule. If you give a highly technical explanation of why the bugs occurred, you will likely confuse your client. If you simply say “we ran into some bugs,” your client might not be satisfied with the explanation. Your job would be to figure out how much technical knowledge your audience has, then find a way to communicate the problem clearly.

- Needs and interests: To plan your document, you need to know what your audience is going to expect from that document. Imagine how readers will want to use your document and what will they demand from it. For example, imagine you are writing a manual on how to use a new smart phone—what are your readers going to expect to find in it? Will they expect it to be in print or will they look for the information online? Would they rather watch a series of Youtube videos?

- Different cultures: If you write for an international audience, be aware that formats for indicating time and dates, monetary amounts, and numerical amounts vary across the globe. Also be aware that humour and figurative language (as in “hit a home run”) are not likely to be understood outside of your own culture. Ideally, your company should employ someone from within that culture to ensure that the message is appropriate, especially if it’s an important message.

- Other demographic characteristics: There are many other characteristics about your readers that might have an influence on how you should design and write your document—for example, age groups, type of residence, area of residence, gender, political preferences, and so on.

Audience analysis can get complicated by other factors, such as mixed audience types for one document and wide variability within the audience.

- More than one audience: You may often find that your business message is for more than one audience. For example, it may be seen by technical people (experts and technicians) and administrative people (executives). What to do? You can either write all the sections so that all the audiences of your document can understand them (good luck!), or you can write each section strictly for the audience that would be interested in it, then use headings and section introductions to alert your audience about where to go and what to avoid in your report.

- Wide variability in an audience: You may realize that, although you have an audience that fits into only one category, there is a wide variability in its background. This is a tough one—if you write to the lowest common denominator of reader, you’re likely to end up with a cumbersome, tedious book-like thing that will turn off the majority of readers. But if you don’t write to that lowest level, you lose that segment of your readers. What to do? Most writers go for the majority of readers and sacrifice that minority that needs more help. Others put the supplemental information in appendices or insert cross-references to beginners’ books.

In the workplace, communicators analyze their audience in a number of ways. If your audience is specific (for example, if you’re writing a report to a particular person), you may draw on past experience, ask a colleague, Google the person or even contact them to ask how they would best like the information. If you’re communicating to a large group, you might use analytics, do user testing or run a focus group.

Unless your project is important, you may not have time to undertake sophisticated audience analysis. In this case, you should follow the most important maxim of workplace communication: don’t waste people’s time. In general, clear, plain language that is clearly arranged will please most audiences. We’ll talk more about Plain Language in the next chapter.

3) Craft Your Message

Let’s say you’ve analyzed your audience until you know them better than you know yourself. What good is it? How do you use this information? How do you keep from writing something that will still be incomprehensible or useless to your readers?

The business of writing to your audience takes a lot of practice. The more you work at it, the more you’ll develop an intuition about how most effectively to reach your audience. But there are some controls you can use to have a better chance to connect with your readers. The following “controls” mostly have to do with making information more understandable for your specific audience:

- Add information readers need to understand your document. Check to see whether certain key information is missing—for example, a critical series of steps from a set of instructions, important background that helps beginners understand the main discussion, or definitions of key terms.

- Omit information your readers do not need. Unnecessary information can also confuse and frustrate readers—after all, it’s there so they feel obligated to read it. For example, you can probably chop theoretical discussion from basic instructions.

- Change the level of the information you currently have. You may have the right information but it may be “pitched” at too high or too low a technical level. It may be pitched at the wrong kind of audience—for example, at an expert audience rather than a technician audience. This happens most often when product-design notes are passed off as instructions.

- Add examples to help readers understand. Examples are one of the most powerful ways to connect with audiences, particularly in instructions. Even in non-instructional text, for example, when you are trying to explain a technical concept, examples are a major help—analogies in particular.

- Change the level of your examples. You may be using examples, but the technical content or level may not be appropriate to your readers.

- Change the organization of your information. Sometimes, you can have all the right information but arrange it in the wrong way. For example, there can be too much background information up front (or too little) such that certain readers get lost. Sometimes, background information needs to be consolidated into the main information—for example, in instructions it’s sometimes better to feed in chunks of background at the points where they are immediately needed.

- Strengthen transitions. It may be difficult for readers, particularly non-specialists, to see the connections between the main sections of your report, between individual paragraphs, and sometimes even between individual sentences. You can make these connections much clearer by adding transition words and by echoing key words more accurately. Words like “therefore,” “for example,” “however” are transition words—they indicate the logic connecting the previous thought to the upcoming thought.

- Write stronger introductions—both for the whole document and for major sections. People seem to read with more confidence and understanding when they have the “big picture”—a view of what’s coming, and how it relates to what they’ve just read. Therefore, make sure you have a strong introduction to the entire document—one that makes clear the topic, purpose, audience, and contents of that document. And for each major section within your document, use mini-introductions that indicate at least the topic of the section and give an overview of the subtopics to be covered in that section.

- Create topic sentences for paragraphs and paragraph groups. It can help readers immensely to give them an idea of the topic and purpose of a section (a group of paragraphs) and in particular to give them an overview of the subtopics about to be covered.

- Change sentence style and length. How you write—down at the individual sentence level—can make a big difference too. In instructions, for example, using imperative voice and “you” phrasing is vastly more understandable than the passive voice or third-personal phrasing. Passive, person-less writing is harder to read—put people and action in your writing. Similarly, go for active verbs as opposed to be verb phrasing. All of this makes your writing more direct and immediate—readers don’t have to dig for it. Sentence length matters as well. An average of somewhere between 15 and 25 words per sentence is about right; sentences over 30 words are often mistrusted.

- Work on sentence clarity and economy. This is closely related to the previous “control” but deserves its own spot. Often, writing style can be so wordy that it is hard or frustrating to read. When you revise your rough drafts, put them on a diet—go through a draft line by line trying to reduce the overall word, page or line count by 20 percent. Try it as an experiment and see how you do. You’ll find a lot of fussy, unnecessary detail and inflated phrasing you can chop out.

- Use more or different graphics. For non-specialist audiences, you may want to use more graphics—and simpler ones at that. Graphics for specialists are more detailed and more technical.

- Break text up or consolidate text into meaningful, usable chunks.For non-specialist readers, you may need to have shorter paragraphs.

- Add cross-references to important information. In technical information, you can help non-specialist readers by pointing them to background sources. If you can’t fully explain a topic on the spot, point to a section or chapter where it is.

- Use headings and lists. Readers can be intimidated by big dense paragraphs of writing, uncut by anything other than a blank line now and then. Search your rough drafts for ways to incorporate headings—look for changes in topic or subtopic. Search your writing for listings of things—these can be made into vertical lists. Look for paired listings such as terms and their definitions—these can be made into two-column lists. Of course, be careful not to force this special formatting—don’t overdo it.

- Use special typography, and work with margins, line length, line spacing, type size, and type style. You can do things like making the lines shorter (bringing in the margins), using larger type sizes, and other such tactics. Certain type styles are believed to be friendlier and more readable than others.

4) Choose Your Medium/Product

Analyzing your purpose, audience and message will lead you to your medium, which is how the message is communicated. Should your message be a letter? A memo? An email? A text? A GIF?

For example, we have discussed a simple and traditional channel of written communication: the hard-copy letter mailed in a standard business envelope and sent by postal mail. But in today’s business environment, this channel is becoming increasingly rare as electronic channels become more widely available and accepted.

When is it appropriate to send an instant message or text message versus a conventional e-mail? What is the difference between a letter and a memo? Between a report and a proposal? Writing itself is the communication medium, but each of these specific channels has its own strengths, weaknesses, and understood expectations that are summarized in Table 2.5.1.

| Channel | Strengths | Weaknesses | Expectations | When to choose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instant message or text message |

Very fast Good for rapid exchanges of small amounts of informationInexpensive |

Informal Not suitable for large amounts of information Abbreviations lead to misunderstandings |

Quick response |

Informal use among peers at similar levels within an organization You need a fast, inexpensive connection with a colleague over a small issue and limited amount of information |

|

Fast Good for relatively fast exchanges of information “Subject” line allows compilation of many messages on one subject or project Easy to distribute to multiple recipients Inexpensive |

May be overlooked or deleted without being read. Large attachments may cause the e-mail to be caught in recipient’s spam filter (though this can be remedied by using Dropbox) Tone may be lost, causing miscommunications. |

Normally a response is expected within 24 hours, although norms vary by situation and organizational culture |

You need to communicate but time is not the most important consideration You need to send attachments (provided their file size is not too big) |

|

| Fax |

Fast Provides documentation |

Very few businesses have a fax machine anymore, unless you work in the legal or medical field. |

Normally, a long (multiple page) fax is not expected |

You want to send a document whose format must remain intact as presented, such as a medical prescription or a signed work order |

| Memo |

Official but less formal than a letter Clearly shows who sent it, when, and to whom |

Memos sent through e-mails can get deleted without review Sending to many recipients (without using an email delivery CRM like MailChimp) can cause your message to get stuck in a spam filter. |

Normally used internally in an organization to communicate directives from management on policy and procedure, or documentation |

You need to communicate a general message within your organization |

| Letter |

Formal Letterhead represents your company and adds credibility |

May get filed or thrown away unread Cost and time involved in printing, stuffing, sealing, affixing postage, and travel through the postal system |

Specific formats associated with specific purposes |

You need to inform, persuade, deliver bad news or negative message, and document the communication |

| Report |

Can require significant time for preparation and production |

Requires extensive research and documentation |

Specific formats for specific purposes |

You need to document the relationship(s) between large amounts of data to inform an internal or external audience |

| Proposal |

Can require significant time for preparation and production |

Requires extensive research and documentation |

Specific formats for specific purposes |

You need to persuade an audience with complex arguments and data |

By choosing the correct channel for a message, you can save yourself many headaches and increase the likelihood that your writing will be read, understood, and acted upon in the manner you intended.

In terms of writing preparation, you should review any electronic communication before you send it. Spelling and grammatical errors will negatively impact your credibility. With written documents, we often take time and care to get it right the first time, but the speed of instant messaging, text messaging, or emailing often deletes this important review cycle of written works. Just because the document you prepare in a text message is only one sentence long doesn’t mean it can’t be misunderstood or expose you to liability. Take time when preparing your written messages, regardless of their intended presentation, and review your work before you click “send.”

To further explore the CMAPP model, click on the hotspots below.

Let’s wrap up by seeing these principles in action.

Attribution

“Applying the Communication Process” from Business Writing For Everyone by Arley Cruthers is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.