7.5: Spotlight on Social Media Use

This chapter is designed to provide you with an opportunity to reflect on various aspects of professional communication in the digital age. Each curated “Spotlight” section, while not exhaustive, provides some background into an aspect of digital communication followed by a “Getting Plugged In”, “Getting Real”, or a “Getting Competent” section, which asks you to apply your own insight to a series of guided questions.

Self-Presentation and Public Image

In general, we strive to present a public image that matches up with our self-concept, but we can also use self-presentation strategies to enhance our self-concept (Hargie, 2011). When we present ourselves in order to evoke a positive evaluative response, we are engaging in self-enhancement. In the pursuit of self-enhancement, a person might try to be as appealing as possible in a particular area or with a particular person to gain feedback that will enhance one’s self-esteem. For example, a singer might train and practice for weeks before singing in front of a well-respected vocal coach but not invest as much effort in preparing to sing in front of friends. Although positive feedback from friends is beneficial, positive feedback from an experienced singer could enhance a person’s self-concept. Self-enhancement can be productive and achieved competently, or it can be used inappropriately. Using self-enhancement behaviors just to gain the approval of others or out of self-centeredness may lead people to communicate in ways that are perceived as phony or overbearing and end up making an unfavorable impression (Sosik, Avolio, & Jung, 2002, p. 217).

Spotlight: “Getting Plugged In”

Spotlight: “Getting Plugged In”

Self-Presentation Online: Social Media, Digital Trails, and Your Reputation

Although social networking has long been a way to keep in touch with friends and colleagues, the advent of social media has made the process of making connections and those all-important first impressions much more complex. Just looking at Facebook as an example, we can clearly see that the very acts of constructing a profile, posting status updates, “liking” certain things, and sharing various information via Facebook features and apps is self-presentation (Kim & Lee, 2011, p. 360). People also form impressions based on the number of friends we have and the photos and posts that other people tag us in. All this information floating around can be difficult to manage. So how do we manage the impressions we make digitally given that there is a permanent record?

Research shows that people overall engage in positive and honest self-presentation on Facebook (Kim & Lee, 2011, p. 360). Since people know how visible the information they post is, they may choose to only reveal things they think will form favorable impressions. But the mediated nature of Facebook also leads some people to disclose more personal information than they might otherwise disclose in a public/ semipublic forum. These hyperpersonal disclosures may result in negative impressions/ reactions from other users. In general, the ease of digital communication, not just on Facebook, has presented new challenges for our self-control and information management. Sending someone a sexually provocative image used to take some effort before the age of digital cameras, but now “sexting” (sending an explicit photo) takes a few seconds. Some people who would have likely not engaged in such behavior before are more tempted to do that now, and it is the desire to present oneself as desirable or cool that leads people to send photos they may later regret having sent (DiBlasio, 2012). New technology in the form of apps is trying to give people a little more control over the exchange of digital information. An iPhone app called “Snapchat” allows users to send photos that will only be visible for a few seconds. Although this isn’t a guaranteed safety net, the demand for such apps is increasing.This confirms the point that we all now leave digital trails of information that can be useful in terms of our self-presentation but can also create new challenges in terms of managing the information floating around from which others may form impressions of us.

- What impressions do you want people to form of you based on the information they can see on your Facebook page?

- Have you ever used social media or the Internet to do “research” on a person? What things would you find favorable and unfavorable?

- Do you have any guidelines you follow regarding what information about yourself you will put online or not? If so, what are they? If not, why?

Return to the Chapter Section menu

Self-Disclosure and Interpersonal Communication

Theories of Self-Disclosure

Social penetration theory states that as we get to know someone, we engage in a reciprocal process of self-disclosure that changes in breadth and depth and affects how a relationship develops. Depth refers to how personal or sensitive the information is, and breadth refers to the range of topics discussed (Greene, Derlega, & Mathews, 2006, pp. 412-13). You may recall Shrek’s declaration that ogres are like onions in the movie Shrek. While certain circumstances can lead to a rapid increase in the depth and/or breadth of self-disclosure, the theory states that in most relationships people gradually penetrate through the layers of each other’s personality like we peel layers from an onion.

The theory also argues that people in a relationship balance needs that are sometimes in tension, which is a dialectic. This could be compared to walking a tightrope: we have to lean to one side and eventually lean to another side to keep ourselves balanced and avoid falling. The constant back and forth allows us to stay balanced, even though we may not always be even, or standing straight up. One of the key dialectics that must be negotiated is the tension between openness and closedness (Greene, Derlega, & Mathews, 2006, pp. 412-13). We want to make ourselves open to others through self-disclosure, but we also want to maintain a sense of privacy.

We may also engage in self-disclosure for the purposes of social comparison. Social comparison theory states that we evaluate ourselves based on how we compare with others (Hargie, 2011). We may disclose information about our intellectual aptitude or athletic abilities to see how we relate to others. This type of comparison helps us decide whether we are superior or inferior to others in a particular area. Disclosures about abilities or talents can also lead to self-validation if the person to whom we disclose reacts positively. By disclosing information about our beliefs and values, we can determine if they are the same as or different from those of others. Last, we may disclose fantasies or thoughts to another to determine whether they are acceptable or unacceptable. We can engage in social comparison as the discloser or the receiver of disclosures, which may allow us to determine whether or not we are interested in pursuing a relationship with another person.

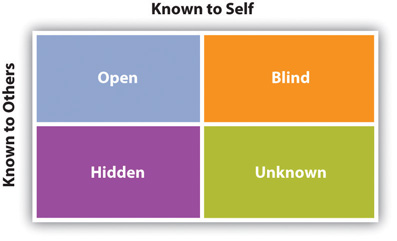

The final theory of self-disclosure that we will discuss is the Johari window, which is named after its creators Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham (Luft, 1969). The Johari window can be applied to a variety of interpersonal interactions in order to help us understand what parts of ourselves are open, hidden, blind, and unknown. To understand the concept, think of a window with four panes. As you can see in Figure 7.5.1 “Johari Window”, one axis of the window represents things that are known to us, and the other axis represents things that are known to others. The upper left pane contains open information that is known to us and to others. The amount of information that is openly known to others varies based on relational context. When you are with close friends, there is probably a lot of information already in the open pane, and when you are with close family, there is also probably a lot of information in the open pane. The information could differ, though, as your family might know much more about your past and your friends more about your present. Conversely, there isn’t much information in the open pane when we meet someone for the first time, aside from what the other person can guess based on our nonverbal communication and appearance.

Figure 7.5.1 Johari Window

The bottom left pane contains hidden information that is known to us but not to others. As we are getting to know someone, we engage in self-disclosure and move information from the “hidden” to the “open” pane. By doing this, we decrease the size of our hidden area and increase the size of our open area, which increases our shared reality. The reactions that we get from people as we open up to them help us form our self-concepts and also help determine the trajectory of the relationship. If the person reacts favorably to our disclosures and reciprocates disclosure, then the cycle of disclosure continues and a deeper relationship may be forged.

The upper right pane contains information that is known to others but not to us. For example, we may be unaware of the fact that others see us as pushy or as a leader. We can see that people who have a disconnect between how they see themselves and how others see them may have more information in their blind pane. Engaging in perception checking and soliciting feedback from others can help us learn more about our blind area.

The bottom right pane represents our unknown area, as it contains information not known to ourselves or others. To become more self-aware, we must solicit feedback from others to learn more about our blind pane, but we must also explore the unknown pane. To discover the unknown, we have to get out of our comfort zones and try new things. We have to pay attention to the things that excite or scare us and investigate them more to see if we can learn something new about ourselves. By being more aware of what is contained in each of these panes and how we can learn more about each one, we can more competently engage in self-disclosure and use this process to enhance our interpersonal relationships.

Spotlight: “Getting Plugged In”

Self-Disclosure and Social Media

Facebook and Twitter are undoubtedly dominating the world of online social networking, and the willingness of many users to self-disclose personal information ranging from moods to religious affiliation, relationship status, and personal contact information has led to an increase in privacy concerns. Facebook and Twitter offer convenient opportunities to stay in touch with friends, family, and coworkers, but are people using them responsibly? Some argue that there are fundamental differences between today’s digital natives, whose private and public selves are intertwined through these technologies, and older generations (Kornblum, 2007). Even though some colleges are offering seminars on managing privacy online, we still hear stories of self-disclosure gone wrong, such as the football player from the University of Texas who was kicked off the team for posting racist comments about President Obama or the student who was kicked out of a private Christian college after a picture of him dressed in drag surfaced on Facebook. However, social media experts say these cases are rare and that most students are aware of who can see what they’re posting and the potential consequences (Nealy, 2009, p. 13). The issue of privacy management on Facebook is affecting parent-child relationships, too, and as the website “Oh Crap. My Parents Joined Facebook.” shows, the results can sometimes be embarrassing for the college student and the parent as they balance the dialectic between openness and closedness once the child has moved away.

- How do you manage your privacy and self-disclosures online?

- Do you think it’s ethical for school officials or potential employers to make admission or hiring decisions based on what they can learn about you online? Why or why not?

- Are you or would you be friends with a parent on Facebook? Why or why not? If you already are friends with a parent, did you change your posting habits or privacy settings once they joined? Why or why not?

Return to the Chapter Section menu

Crisis Communication

Crisis communication is a fast-growing field of study within communication studies as many businesses and organizations realize the value in finding someone to prepare for potential crises, interact with stakeholders during a crisis, and assess crisis responses after they have occurred. Crisis communication occurs as a result of a major event outside of normal expectations that has potential negative results, runs the risk of escalating in intensity, may result in close media or government scrutiny, and creates pressure for a timely and effective response (Zaremba, 2010, pp. 20-22) Some examples of crises include natural disasters, management/employee misconduct, product tampering or failure, and workplace violence.

The need for crisis communication professionals is increasing, as various developments have made organizations more susceptible to crises (Coombs, 2012, p. 14). Since the 1990s, organizations have increasingly viewed their reputations as assets that must be protected. Whereas reputations used to be built on word-of-mouth communication and one-on-one relationships, technology, mass media, and now social media have made it easier for stakeholders to praise or question an organization’s reputation. A Facebook post or a Tweet can now turn into widespread consumer activism that organizations must be able to respond to quickly and effectively. In addition, organizations are being held liable for “negligent failure to plan,” which means that an organization didn’t take “reasonable action to reduce or eliminate known or reasonably foreseeable risks that could result in harm” (Coombs, 2012, p. 14). Look around your classroom and the academic building you are in. You will likely see emergency plans posted that may include instructions on what to do in situations ranging from a tornado, to a power outage, to an active shooter. As a response to the mass shooting that took place at Virginia Tech in 2006, most colleges and universities now have emergency notification systems and actively train campus police, faculty, and staff on what to do in the case of an active shooter on campus. Post–Virginia Tech, a campus’s failure to institute such procedures could be deemed as negligent failure to plan if a similar incident were to occur on that campus.

Crisis communicators don’t just interact with the media; they communicate with a variety of stakeholders. Stakeholders are the various audiences that have been identified as needing information during a crisis. These people and groups have a “stake” in the organization or the public interest or as a user of a product or service. Internal stakeholders are people within an organization or focal area, such as employees and management. External stakeholders are people outside the organization or focal area such as customers, clients, media, regulators, and the general public (Zaremba, 2010, pp. 20-22).

Four main areas of crisis communication research are relationships, reputation, responsibility, and response (Zaremba, 2010, pp. 20-22). Relationships and reputation are built and maintained before a crisis occurs. Organizations create relationships with their stakeholders, and their track record of quality, customer service, dependability, and communication determines their reputation. Responsibility refers to the degree to which stakeholders hold an organization responsible for the crisis at hand. Judgments about responsibility vary depending on the circumstances of a crisis. An unpreventable natural disaster will be interpreted differently than a product failure resulting from cutting corners on maintenance work to save money. Response refers to how an organization reacts to a crisis in terms of its communication and behaviors.

Spotlight: “Getting Real”

Crisis Communication Professionals

Crisis communication professionals create crisis communication plans that identify internal and external audiences that need information during crisis events. Effective crisis communication plans can lessen the impact of or even prevent crises. Aside from that, communicators also construct the messages to be communicated to the stakeholders and select the channels through which those messages will be sent. The crisis communicator or another representative could deliver a speech or press conference, send messages through social media, send e-mail or text message blasts out, or buy ad space in newspapers or on television (Zaremba, 2010, , pp. 20-22).

Crisis communicators must have good public speaking skills. Communicating during a crisis naturally increases anxiety, so it’s important that speakers have advanced skills at managing anxiety and apprehension. In terms of delivery, while there are times when impromptu responses are necessary—for example, during a question-and-answer period—manuscript or extemporaneous delivery are the best options. It is also important that a crisis communicator be skilled at developing ethos, or credibility as a speaker. This is an important part of the preparatory stages of crisis communication, when relationships are formed and reputations are established. The importance of ethos is related to the emphasis on honesty and disclosure over stonewalling and denial.

A myth regarding crisis communicators is that their goal is to “spin” a message to adjust reality or create an illusion that makes their organization look better. While some crisis communicators undoubtedly do this, it is not the best practice in terms of effectiveness, competence, or ethics. Crisis communication research and case studies show that honesty is the best policy. A quick and complete disclosure may create more scrutiny or damage in the short term, but it can minimize reputational damage in the long term (Zaremba, 2010, pp. 20-22). Denying a problem, blaming others instead of taking responsibility, or ignoring a problem in hopes that it will go away may prolong media coverage, invite more investigation, and permanently damage an organization’s image.

- Why do you think extemporaneous and manuscript delivery are the preferred delivery methods for crisis communicators? What do these delivery styles offer that memorized and impromptu do not? In what situations would it be better to have a manuscript? To deliver extemporaneously?

- How do social media sources of information impact companies and public institutions’ ability to “spin” a message?

Return to the Chapter Section menu

Monetizing The Internet and Digital Media

The birth of the Internet can be traced back to when government scientists were tasked with creating a means of sharing information over a network that could not be interrupted, accidentally or intentionally. More than thirty years ago, those government scientists created an Internet that was much different from what we think of as the Internet today. The original Internet was used as a means of sharing information among researchers, educators, and government officials. That remained its main purpose until the Cold War began to fade and the closely guarded information network was opened up to others. At this time, only a small group of computer enthusiasts and amateur hackers made use of the Internet, because it was still not accessible to most people. Some more technological advances had to occur for the Internet to become the mass medium that it is today.

Tim Berners-Lee is the man who made the Internet functional for the masses. In 1989, Berners-Lee created new computer-programming codes that fixed some problems that were limiting the growth of the Internet as a mass medium (Biagi, 2007, p. 173-74). The main problem was that there wasn’t a common language that all computers could recognize and use to communicate and connect. He solved this problem with the creation of the hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP), which allows people to make electronic connections or links to information on other computers or servers. He also invented hypertext markup language (HTML), which gave users a common language with which to create and design online content. Berners-Lee also invented the first browser, which allowed people to search out information and navigate the growing number of interconnections among computers. Berners-Lee named his new network the “World Wide Web,” and he put all his inventions into the public domain so that anyone could use and adapt them for free, which undoubtedly contributed to the web’s exploding size. The growing web was navigable using available browsers, but it was sometimes like navigating in the ocean with no compass, a problem that led to the creation of search engines.

A major source of revenue generated by the Internet goes to Internet service providers (ISPs), who charge customers for Internet access. The more reliable and fast the connection, the more expensive the service. Unsurprisingly, old media providers like cable companies (who were competing against satellite companies) and phone companies (who were also struggling after the growth of cell phone and e-mail communication) are the largest providers of high-speed Internet access. In the late 2000s, these companies were bringing in more than $30 billion a year from these services (Biagi, 2007, p. 173-74).

Many others make money from the web through traditional exchanges of goods or services for money or by selling space to advertisers. These methods of commerce are not new, as they were used in print, radio, and television. Online auction sites like eBay and online stores like Amazon simply moved a traditional commercial exchange to cyberspace. Advertising online, however, is different in some ways from advertising in other media. Old media advertisers measure their success with ads based on a corresponding increase or decrease in sales—a method that is not very precise or immediate. Online advertisers, on the other hand, can know exactly how many people see their ads based on the number of site visitors, and they can measure how effective their ad is by how many people click on it. This allows them to revise, pull, or buy more of an ad quickly based on the feedback. Additionally, certain online environments provide even more user data to advertisers, which allows them to target ads. If you, for example, search for “vacation rentals on Lake Michigan” using a search engine, ads for lake houses or vacation spots may also show up. The social networks that people create on the Internet also create potential for revenue generation. In fact, many people have started to take advantage of this potential by monetizing their personal or social media sites, which you can read more about in the “Getting Real” box.

Spotlight: “Getting Real”

Monetizing the Web: Entrepreneurship and Digital/Social Media

People have been making money off the web for decades now, but sites like eBay really opened their eyes, for the first time, to the possibility of spinning something they already have/ already do into extra cash. Anyone can establish a web presence through starting a website, building a profile on an existing website like a blog-hosting service, or using an already existing space like a Facebook or Twitter account they already have. If you are interested in trying to make money that way, you’d have to think about what you can offer and who might want that. For example, if you have a blog that attracts a regular stream of readers because they like your posts about the weekend party scene in your city, you might be able to utilize a service like Google’s AdSense to advertise on your page and hope that some of your readers click the ads. In this case, you’re offering content that attracts readers to advertisers. This is a pretty traditional way of making money through advertising, just as with newspapers and billboards.

Less conventional means of monetizing the web involve harnessing the power of social media. In this capacity, you can extend your brand or the brand of something/someone else. To extend your brand, you first have to brand yourself. Determine what you can offer people—consulting in your area of expertise such as voice lessons, entertainment such as singing at weddings, delivering speeches or writing about your area of expertise, and so on. Then create a web presence that you can direct people back to through your social media promotion. If you have a large number of followers on Twitter, for example, other brands may want to tap into your ability to access that audience to have you promote their product or service. If you follow any celebrities on Twitter, you are well aware that many of their tweets link to a product that they say they love or a website that’s offering a special deal. The marketing agency Adly works with celebrities and others who have a large Twitter audience to send out sponsored tweets from more than 150 different advertisers (Friel, 2011). Some movie studios now include in actors’ contracts terms that require them to make a certain number of social mentions of the project on all their social media sites. Another online company, MyLikes, works with regular people, too, not just celebrities, to help them monetize their social media accounts (Davila, 2012).

- How do you think your friends would react if you started posting messages that were meant to make you money rather than connect with them?

- Do you have a talent, service, or area of expertise that you think you could spin into some sort of profit using social or digital media?

- What are some potential ethical challenges that might arise from celebrities using their social media sites for monetary gain? What about for people in general?

Return to the Chapter Section menu

New Media and Society

Media studies pioneer Marshall McLuhan emphasized, long before what we now call “new media” existed, that studying media and technology can help us understand our society. He didn’t believe that we could study media without studying society, as the two are bound together (Siapera, 2012). The ongoing switch from analogue to digital, impersonal to personal/social, and one-way to dialogic media is affecting our society in multiple ways.

The days of analogue media are coming to an end — indeed, they are over in many places. Digital television conversion is complete in North America and the European Union, and many old media formats are being digitalized—for example, books and documents scanned into PDFs, old home movies being turned into DVDs, and record players with USB outputs digitizing people’s vinyl collections.

These technological changes haven’t solved some problems carried over from old media. Some of the same problems with representation and access for which the mass media were criticized are still present in new media, despite its democratizing potential. As discussed earlier, new media increase participation and interactivity, giving audience members and users more control over content and influence over media decisions. However, as media critics point out, participants are not equally distributed (Jenkins, 2006). Research shows that new media users, especially heavy users who are more actively engaged, tend to be male, middle class, and white.

Still, many scholars and reporters have noted the democratizing effect of new media — the ways in which new media distribute power to the people through their personal and social characteristics. This is, at least in part, a positive and more active and participative alternative to passive media consumption (Siapera, 2012). Instead of the powerful media outlets exclusively having control over what is communicated to audiences and serving as the sole gatekeeper, media-audience interactions are now more like a dialogue. The personal access to media and growing control over media discourses by users allows people to more freely express opinions, offer criticisms, and question others—communicative acts that are all important for a functioning democracy.

A recent national survey found that people in the fifteen to twenty-five age group are using new media to engage with peers on political issues.[1] The survey found that young people are defying traditional notions of youthful political apathy by using new media platforms to do things like start online political groups, share political videos using social media, or circulate news stories about political issues.

These activities were not included in previous research done on the political habits of young people because those surveys typically focused on more traditional forms of political engagement like voting, joining a political party, or offline campaigning. Political engagement using new media is viewed as more participatory, since people can interact with their peers without having to go through official channels or institutions. But the research also found that this type of participatory political engagement also led to traditional engagement, as those people were twice as likely to vote in the actual election.[2]

In addition, although the digital divide is a continuing ethical issue, new media have had a more positive effect on places that are often left out of such technological development. For example, although many people in developing countries still do not have access to dependable electricity or water, they may have access to a cell phone or the Internet through NGO programs or Internet cafés. Many people, especially North Americans, may think the days of Internet cafés (also called cyber cafés) are over. Although Internet cafés were never as popular or numerous on our continent, communal and public Internet access is still an important part of providing access to the Internet all around the world (Liff & Lægran, 2003).

Spotlight: “Getting Plugged In”

Social Media and the 2012 Presidential Election

The US presidential election of 2012 has been called the “social media election.” For the first time, many people took to their Facebook timelines and/or Twitter feeds to announce who they planned on voting for or to encourage others to vote for a particular candidate. In fact, about 25 percent of registered voters told their Facebook friends and Twitter followers who they would vote for (Byers, 2012). Candidates are aware of the growing political power of social media, as evidenced by the fact that, for the first time, major campaigns now include a “digital director” as one of their top-level campaign staffers (Friess, 2012). These “social media gurus” are responsible for securing targeted advertising on outlets such as Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Pinterest, and Reddit (among others), which now have the capability to narrowcast to specific geographical areas and user demographics. Digital directors are also responsible for developing strategies to secure Facebook “likes,” Twitter followers, and retweets. Smartphones also present new options for targeted messaging, as some ads on mobile apps were “geotargeted” to people riding a certain bus or attending a specific public event (Friess, 2012).

Aside from new methods of advertising, social media also helped capture the much-anticipated 2012 Election Day, including some of the barriers or problems people experienced. People used YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook to document and make public their voting experience. One voter in Pennsylvania recorded a video of a voting machine that kept switching to Romney/Ryan every time the person tried to choose Obama/Biden, and before the day was over, the video already had more than two million views (Balke, 2012). People also used social media to document long lines at polling places and to share the incoming election results. 20 million tweets were posted on election night and the hashtag “#election2012” was used more than 11 million times. When Obama’s campaign tweeted “Four more years” after he had been declared the winner, it was retweeted more than 225,000 times (Bello, 2012).

- How did you and/or your friends and family use social media during recent election events at the local or federal level?

- What are some of the positives and negatives of the increasingly central role that social media play in politics?

Return to the Chapter Section menu

New Media and Interpersonal Relationships

New media have been the primary communication change of the past few generations. Some scholars in sociology have decried the negative effects of new technology on society and relationships in particular, saying that the quality of relationships is deteriorating and the strength of connections is weakening (Richardson & Hessey, 2009, p. 29).

Facebook greatly influenced our use of the word friend, although people’s conceptions of the word may not have changed as much. When someone “friends you” on Facebook, it doesn’t automatically mean that you now have the closeness and intimacy that you have with some offline friends — and research shows that people don’t regularly accept friend requests from or send them to people they haven’t met, preferring instead to have met a person at least once (Richardson & Hessey, 2009, p. 29). Some users, though, especially adolescents, engage in what is called “friend-collecting behavior,” which entails users friending people they don’t know personally or that they wouldn’t talk to in person in order to increase the size of their online network (Christofides, Muise, & Desmarais, 2012). As we will discuss later, this could be an impression management strategy, as the user may assume that a large number of Facebook friends will make him or her appear more popular to others.

Although many have critiqued the watering down of the term friend when applied to SNSs, specifically Facebook, some scholars have explored how the creation of these networks affects our interpersonal relationships and may even restructure how we think about our relationships. Even though a person may have hundreds of Facebook friends that he or she doesn’t regularly interact with on- or offline, just knowing that the network exists in a somewhat tangible form (catalogued on Facebook) can be comforting. Even the people who are distant acquaintances but are “friends” on Facebook can serve important functions. A dormant network is a network of people with whom users may not feel obligated to explicitly interact, but whose existence is still perceived as comforting by users. Such networks can be beneficial, because when needed, a person may be able to more easily tap into that dormant network than they would an offline extended network. It’s almost like being friends on Facebook keeps the communication line open, because both people can view the other’s profile and keep up with their lives even without directly communicating. This can help sustain tenuous friendships or past friendships and prevent them from fading away, which is a common occurrence as we go through various life changes.

A key part of interpersonal communication is impression management, and some forms of new media allow us more tools for presenting ourselves than others. Social networking sites (SNSs) in many ways are platforms for self-presentation. Even more than blogs, web pages, and smartphones, the environment on an SNS like Facebook or Twitter facilitates self-disclosure in a directed way and allows others who have access to our profile to see our other “friends.” This convergence of different groups of people (close friends, family, acquaintances, friends of friends, colleagues, and strangers) can present challenges for self-presentation. Although Facebook is often thought of as a social media outlet for teens and young adults, research shows half of all US adults have a profile on Facebook or another SNS (Vitak & Ellison, 2012). The fact that Facebook is expanding to different generations of users has coined a new phrase—“the graying of Facebook.” This is due to a large increase in users over the age of fifty-five. In fact, it has been stated the fastest-growing Facebook user group is women fifty-five and older — which, for instance, went up more than 175 percent between 2008-2009 (Gates, 2009). So now we likely have people from personal, professional, and academic contexts in our Facebook network, and those people are now more likely than ever to be from multiple generations. The growing diversity of our social media networks creates new challenges as we try to engage in impression management.

We should be aware that people form impressions of us based not just on what we post on our profiles but also on our friends and the content that they post on our profiles. In short, as in our offline lives, we are judged online by the company we keep (Walther et al., 2008, p. 29). The difference is, though, that via Facebook a person (unless blocked or limited by privacy settings) can see our entire online social network and friends, which doesn’t happen offline. The information on our Facebook profiles is also archived, meaning there is a record that doesn’t exist for offline interactions. Recent research found that a person’s perception of a profile owner’s attractiveness is influenced by the attractiveness of the friends shown on the profile. In short, a profile owner is judged more physically attractive when his or her friends are judged as physically attractive, and vice versa. The profile owner is also judged as more socially attractive (likable, friendly) when his or her friends are judged as physically attractive. The study also found that complimentary and friendly statements made about profile owners on their wall or on profile comments increased perceptions of the profile owner’s social attractiveness and credibility. An interesting, but not surprising, gender double standard also emerged. When statements containing sexual remarks or references to the profile owner’s excessive drinking were posted on the profile, perceptions of attractiveness increased if the profile owner was male and decreased if female (Walther et al., 2008, p. 29).

Self-disclosure is a fundamental building block of interpersonal relationships, and new media make self-disclosures easier for many people because of the lack of immediacy, meaning the fact that a message is sent through electronic means arouses less anxiety or inhibition than would a face-to-face exchange. SNSs provide opportunities for social support. Research has found that Facebook communication behaviors such as “friending” someone or responding to a request posted on someone’s wall lead people to feel a sense of attachment and perceive that others are reliable and helpful (Vitak & Ellison, 2012). Much of the research on Facebook, though, has focused on the less intimate alliances that we maintain through social media. Since most people maintain offline contact with their close friends and family, Facebook is more of a supplement to interpersonal communication. Since most people’s Facebook “friend” networks are composed primarily of people with whom they have less face-to-face contact in their daily lives, Facebook provides an alternative space for interaction that can more easily fit into a person’s busy schedule or interest area. For example, to stay connected, both people don’t have to look at each other’s profiles simultaneously.

The space provided by SNSs can also help reduce some of the stress we feel in regards to relational maintenance or staying in touch by allowing for more convenient contact. The expectations for regular contact with our Facebook friends who are in our extended network are minimal. An occasional comment on a photo or status update or an even easier click on the “like” button can help maintain those relationships. However, when we post something asking for information, help, social support, or advice, those in the extended network may play a more important role and allow us to access resources and viewpoints beyond those in our closer circles. Research shows that many people ask for informational help through their status updates (Vitak & Ellison, 2012).

These extended networks serve important purposes, one of which is to provide access to new information and different perspectives than those we may get from close friends and family. For example, since we tend to have significant others that are more similar to than different from us, the people that we are closest to are likely to share many or most of our beliefs, attitudes, and values. Extended contacts, however, may expose us to different political views or new sources of information, which can help broaden our perspectives.

The content in this section hopefully captures what I’m sure you have already experienced in your own engagement with new media—that new media have important implications for our interpersonal relationships, and that some professional aspects relate to that, too.

Spotlight: “Getting Competent”

Using Social Media Competently

While we can’t control all the information about ourselves online or the impressions people form, we can more competently engage with social media so that we are getting the most out of it in both personal and professional contexts.

A quick search on Google for “social media dos and don’ts” will yield over 100,000 results, which shows that there’s no shortage of advice about how to competently use social media. Let’s go over a few (source: Doyle, 2012).

Be consistent. Given that most people have multiple social media accounts, it’s important to have some degree of consistency. At the top level of your profile (the part that isn’t limited by privacy settings), include information that you don’t mind anyone seeing.

Know what’s out there. The top level of many social media sites is visible in Google search results. About once a month, do a Google search using your full name between quotation marks. Make sure you’re logged out of all your accounts and then click on the various results to see what others can see.

Think carefully before you post. Software enabling people to take “screen shots”/ download videos and tools that archive web pages can be used without your knowledge to create records of what you post. While it is still a good idea to go through your online content and “clean up” materials that may form unfavorable impressions, it is even a better idea to not post that information in the first place. Posting something about how you hate school or your job or a specific person may be done in the heat of the moment and forgotten, but a potential employer might find that information and form a negative impression even if it’s months or years old.

Be familiar with privacy settings. If you are trying to expand your social network, it may be counterproductive to put your Facebook or Twitter account on “lockdown,” but it is beneficial to know what levels of control you have and to take advantage of them. For example, you can use a “Limited Profile” list on Facebook for new contacts or people with whom you are not very close. You can also create groups of contacts on various social media sites so that only certain people see certain information.

Be a gatekeeper for your network. Do not accept friend requests or followers that you do not know. Not only could these requests be sent from “bots” that might skim your personal info or monitor your activity; they could be from people who might make you look bad. Remember, we learned earlier that people form impressions based on those with whom we are connected. You can always send a private message asking the person making the request how he/she knows you, or look up his/her name or username on Google or another search engine.

- Identify information that you might want to limit for each of the following audiences: friends, family, and employers.

- Google your name (use multiple forms and put them in quotation marks). Do the same with any usernames that are associated with your name (e.g., you can Google your Twitter handle or an e-mail address). What information came up? Were you surprised by anything?

- What strategies can you use to help manage the impressions you form on social media?

Return to the Chapter Section menu

References

Biagi, S. (2007). Media/Impact: An introduction to mass media. Wadsworth.

Coombs, W. T. (2012). Ongoing crisis communication: Planning, managing, and responding (3rd ed.). Sage.

Christofides, E., Muise, A. & Desmarais, S. (2012). “Hey Mom, What’s on Your Facebook?” Comparing Facebook disclosure and privacy in adolescents and adults Social Psychological and Personality Science 3(1), 48-54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611408619

Davila, D. (2011). How Twitter celebrities monetize their accounts. Idaconcpts. http://idaconcpts.com/2011/01/11/how-twitter-celebrities-monetize-their-accounts.

DiBlasio, N. (2012, May 7). Demand for photo-erasing iPhone app heats up sexting debate. USA Today. http://content.usatoday.com/communities/ondeadline/post/2012/05/demand-for-photo-erasing-iphone-app-heats-up-sexting-debate/1.

Doyle, A. (2012). Top 10 Social Media Dos and Don’ts. http://jobsearch.about.com/od/onlinecareernetworking/tp/socialmediajobsearch.htm.

Gates, A. (2009, March 19). For Baby Boomers, the joys of Facebook. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/22/nyregion/new-jersey/22Rgen.html.

Greene, K., Derlega, V.D. and Mathews, A. (2006). Self-disclosure in personal relationships. In A. L. Vangelisti & D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (pp. 409–427). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606632.023

Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled interpersonal interaction: Research, theory, and practice. Routledge.

Kim, J. & Lee, J.-E. R. (2011). The Facebook paths to happiness: Effects of the number of Facebook friends and self-presentation on subjective well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 14(6), 359-364. DOI: 10.1089/cyber.2010.037

Kornblum, J. (2007, October 23). Privacy? That’s old-school: Internet generation views openness in a different way. USA Today, 1D.

Luft, J. (1969). Of human interaction. National Press Books.

Nealy, M. J. (2009). The new rules of engagement. Diverse: Issues in Higher Education 26(3), 13.

Richardson, K. & Hessey, S. (2009) Archiving the self? Facebook as biography of social and relational memory. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 7, 25-38. https://doi.org/10.1108/14779960910938070

Sosik, J. J., Avolio, B. J., & Jung, D.I. (2012). Beneath the mask: Examining the relationship of self-presentation attributes and impression management to charismatic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 13, 216-24s. DOI: 10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00102-9

Vitak, J. & Ellison, N. B. (2013). “There’s a network out there you might as well tap”: Exploring the benefits of and barriers to exchanging informational and support-based resources on Facebook. New Media and Society 15(2), 243-259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812451566

Walther, J. B., Van Der Heide, B., Kim, S.-Y., Westerman, D. and Tom Tong, S. (2008). The role of friends’ appearance and behavior on evaluations of individuals on Facebook: Are we known by the company we keep? Human Communication Research 34(1), 28-49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2007.00312.x

Zaremba, A. J. (2010). Crisis communication: Theory and practice. M. E. Sharp.