1.2: The Communication Process

Learning Objectives

- Identify and define the components of the transmission model of communication.

- Identify and define the components of the interaction model of communication.

- Identify and define the components of the transaction model of communication.

- Compare and contrast the three models of communication.

- Use the transaction model of communication to analyze a recent communication encounter.

Models of communication simplify the process by providing a visual representation of the various aspects of a communication encounter. In so doing, while somewhat limiting, models allow us to see specific aspects and steps of the process of communication, define communication, and apply communication concepts. When you become aware of how communication functions, you can think more deliberately through your communication encounters, which can help you better prepare for future communication and learn from your previous communication (something we previously defined as engaging in metacognitive learning practices). The three models of communication we will briefly discuss are the transmission, interaction, and transaction models.

The transmission model and the interaction model include the following parts: participants (senders and/or receivers), messages (verbal or nonverbal content being conveyed), encoding, decoding, and channels. The internal cognitive process that allows participants to send, receive, and understand messages is the encoding and decoding process. Encoding is the process of turning thoughts into communication. As we will learn later, the level of conscious thought that goes into encoding messages varies. Decoding is the process of turning communication into thoughts (“understanding” the message — but, again, the level of awareness and insight involved varies). Of course, we don’t just communicate verbally—we have various options, or channels for communication. Encoded messages are sent through a channel, or a sensory route on which a message travels, to the receiver for decoding. While communication can be sent and received using any sensory route (sight, smell, touch, taste, or sound), most communication occurs through visual (sight) and/or auditory (sound) channels.

Transmission Model of Communication

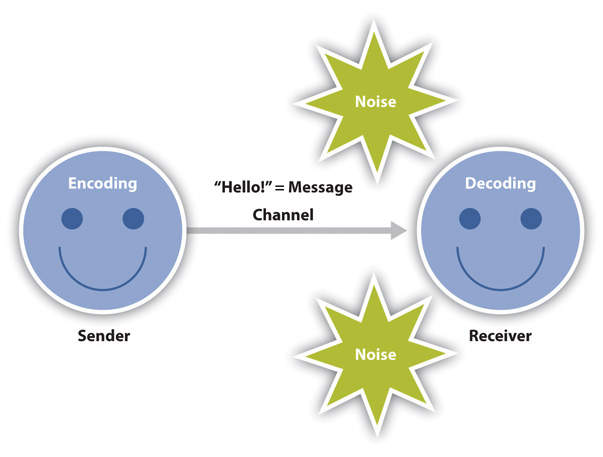

The transmission model of communication describes communication as a linear, one-way process in which a sender intentionally transmits a message to a receiver (Ellis & McClintock, 1990, p. 71). This model focuses on the sender and the message within a communication encounter. Although the receiver is included in the model, this role is viewed as more of a target or end point rather than part of an ongoing process. We are left to presume that the receiver either successfully receives and understands the message or does not. The scholars who designed this model extended on a linear model proposed by Aristotle that included a speaker, a message, and a hearer. They were also influenced by the advent and spread of new communication technologies of the time such as telegraphy and radio, and you can probably see these technical influences within the model (Shannon & Weaver, 1949, p. 16). Think of how a radio message is sent from a person in the radio studio to you listening in your car. The sender is the radio announcer who encodes a verbal message that is transmitted by a radio tower through electromagnetic waves (the channel) and eventually reaches your (the receiver’s) ears via an antenna and speakers in order to be decoded. Radio announcers do not know with certainty if you received their message, but if the equipment is working and the channel is free of static, the message was (likely) successfully received.

Since this model is sender and message focused, responsibility is put on the sender to ensure the message is successfully conveyed. This model emphasizes clarity and effectiveness, but it also acknowledges that there are barriers to effective communication, including noise. Noise is anything that interferes with a message being sent between participants in a communication encounter. Even if a speaker sends a clear message, noise may interfere with a message being accurately received and decoded.

The transmission model of communication accounts for environmental and semantic noise:

- Environmental noise is any physical noise present in a communication encounter. Other people talking in a crowded diner could interfere with your ability to transmit a message and have it successfully decoded.

- Semantic noise is any noise that occurs in the encoding and decoding process when participants do not understand a symbol. To use a technical example, FM antennae can’t decode AM radio signals and vice versa. Likewise, most French speakers can’t decode Swedish and vice versa. Semantic noise can also interfere in communication between people speaking the same language because many words have multiple or unfamiliar meanings.

Although the transmission model may seem simple or even underdeveloped to us today, the creation of this model allowed scholars to examine the communication process in new ways, which eventually led to more complex models and theories of communication that we will discuss more later. This model is not rich enough to fully capture dynamic face-to-face interactions, but there are instances in which communication is one-way and linear — especially computer-mediated communication (CMC). As the following “Getting Plugged In” box explains, CMC is integrated into many aspects of our lives. It has opened up new ways of communicating and brought some new challenges. Think of text messaging for example. The transmission model of communication is well suited for describing the act of text messaging since the sender isn’t sure that the meaning was effectively conveyed or that the message was received. Noise can also interfere with the transmission of a text. If you use an abbreviation the receiver doesn’t know or the phone autocorrects to something completely different than what you meant, then semantic noise has interfered with the message transmission.

Spotlight: “Getting Plugged In”

Computer-Mediated Communication

Many of you reading this textbook probably can’t remember a time without CMC. If that’s the case, then you’re what some scholars have called “the digital generation.” CMC has changed the way we teach and learn, communicate at work, stay in touch with friends, initiate romantic relationships, search for jobs, manage our money, get our news, and participate in our democracy. But the increasing use of CMC has also raised some questions and concerns, even among those of you who are of the digital generation.

In all Professional Communication courses we teach, many of our students choose to do their final research projects on social media use in their industry/field. Many are interested in studying the effects of CMC on employees’ personal and professional lives and relationships.

This desire to study and question CMC may stem from a perception regarding the seeming loss or devaluing of face-to-face (FtF) communication. Additionally, CMC also raises concerns about privacy, cyberbullying, and lack of civility in online interactions. We will continue to explore such issues in the “Getting Plugged In” feature box in each chapter. The following questions emphasize the influence CMC has in your daily communication:

- In a typical day, what types of CMC do you use?

- What are some ways that CMC reduces stress in your life? What are some ways that CMC increases stress in your life? Overall, which of these do you experience more?

- Do you think that today’s society sees less value in FtF communication than we used to? Why/ why not?

Exercises

Getting integrated: Let us examine the following message from a first-year student to a professor:

“Hi there,

I won’t be able to make it to class today. Could you let me know if I’ll be missing anything important?

Kimmie”

The student probably wants to show concern for the missed class. (Otherwise, the students wouldn’t email the professor.) Is that what the message expresses, though?

- Analyze the message and identify any aspects that should be revised.

- Rewrite the message to make it more effective as an expression of the sender’s true intentions.

Interaction Model of Communication

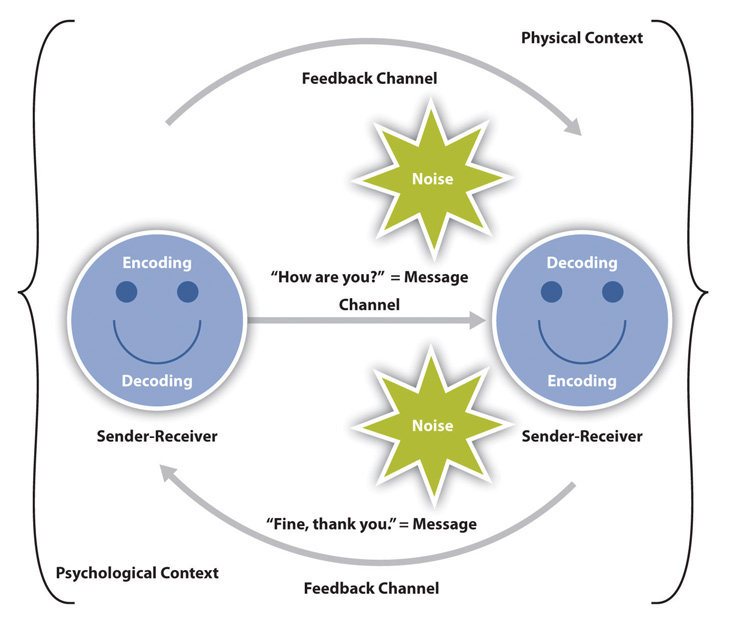

The interaction model of communication describes communication as a process in which participants alternate positions as sender and receiver and generate meaning by sending messages and receiving feedback within physical and psychological contexts (Schramm, 1997). Rather than illustrating communication as a linear, one-way process, the interaction model incorporates feedback, which makes communication a more interactive, two-way process. Feedback includes messages sent in response to other messages. For example, your instructor may respond to a point you raise during class discussion or you may point to the filing cabinet when your coworker asks you where the client file is. The inclusion of a feedback loop also leads to a more complex understanding of the roles of participants in a communication encounter. Rather than having one sender, one message, and one receiver, this model has two sender-receivers who exchange messages. Each participant alternates roles as sender and receiver — sometimes in a deliberate and fully conscious manner, but often very quickly and without full conscious control.

The interaction model is less message-focused and more interaction-focused. While the transmission model focused on how a message was transmitted and whether or not it was received, the interaction model is more concerned with the communication process itself. This model acknowledges that some messages may not be received due to overload (several messages received simultaneously), that some messages are unintentionally sent, etc. Communication isn’t judged effective or ineffective based on whether or not one message was successfully transmitted and received.

The interaction model takes physical and psychological context into account.

- Physical context includes the environmental factors in a communication encounter. The size, layout, temperature, and lighting of a space influence our communication. Imagine being interviewed in a comfortable office by three people vs. in a cold room with uncomfortable chairs by 10 people; having optimal lighting or a source of light in your face; being on a stage as opposed to being in a relatively small meeting room; etc.

- Psychological context includes the mental and emotional factors in a communication encounter. Stress, anxiety, and emotions are just some examples of psychological influences that can affect our communication. Consider contexts such as having to deliver a presentation an hour after receiving some troubling personal news — or how likely you are to disregard a person’s otherwise unacceptable behaviours when you are “love struck.”

Feedback and context help make the interaction model a more useful illustration of the communication process, whereas the next model, the transaction model, views communication as a powerful tool that shapes our realities beyond individual communication encounters.

Transaction Model of Communication

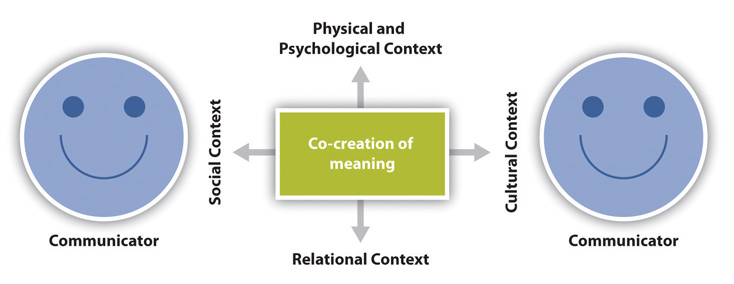

The transaction model differs from the transmission and interaction models in significant ways, including the conceptualization of communication, the role of sender and receiver, and the role of context (Barnlund, 1970). This model describes communication as a process in which communicators generate social realities within social, relational, and cultural contexts. In this model, we don’t just communicate to exchange messages; we communicate to create relationships, form intercultural alliances, shape our self-concepts, and engage with others in dialogue to create communities. In short, we don’t communicate about our realities; communication helps to construct our realities.

Instead of labeling participants as senders and receivers, the people in a communication encounter are referred to as communicators. Unlike the interaction model, which suggests that participants alternate positions as sender and receiver, the transaction model suggests that we are simultaneously senders and receivers. For example, on an interview, as you send verbal messages about your interests and background, the employer reacts nonverbally. You don’t wait until you are done sending your verbal message to start receiving and decoding the nonverbal messages of the employer. Instead, you are simultaneously sending your verbal message and receiving the employer’s nonverbal messages. This is an important addition to the model because it allows us to understand how we are able to adapt our communication—for example, a verbal message—in the middle of sending it based on the communication we are simultaneously receiving from our communication partner.

The transaction model also includes a more complex understanding of context. The interaction model portrays context as physical and psychological influences that enhance or impede communication. While these contexts are important, they focus on message transmission and reception. The transaction model considers how social, relational, and cultural contexts frame and influence our communication encounters.

1. Social context refers to the stated rules or unstated norms that guide communication. As we are socialized into our various communities, we learn rules and implicitly pick up on norms for communicating (e.g., don’t lie to people, don’t interrupt people, don’t pass people in line, greet people when they greet you, thank people when they pay you a compliment, etc.). Parents and teachers often explicitly convey these rules to their children or students. Rules may be stated over and over, and there may be punishment for not following them.

Norms are social conventions that we internalize (or at least learn to recognize) through observation, practice, and trial and error. We may not even know we are breaking a social norm until we notice people looking at us strangely or someone corrects or teases us. For example, as a new employee you may over- or underdress for the company’s holiday party because you don’t know the norm for formality. Although there probably isn’t a stated rule about how to dress at the holiday party, you will notice your error without someone having to point it out, and you will likely not deviate from the norm again in order to save yourself any further embarrassment.

Even though breaking social norms doesn’t result in the formal punishment that might be a consequence of breaking a social rule, the social awkwardness we feel when we violate social norms is usually enough to teach us that these norms are powerful even though they aren’t made explicit like rules. Norms even have the power to override social rules in some situations. To go back to the examples of common social rules mentioned before, we may break the rule about not lying if the lie is meant to save someone from feeling hurt. We often interrupt close friends when we’re having an exciting conversation, but we wouldn’t be as likely to interrupt a professor while they are lecturing. Since norms and rules vary among people and cultures, relational and cultural contexts are also included in the transaction model in order to help us understand the multiple contexts that influence our communication.

2. Relational context includes the previous interpersonal history and type of relationship we have with a person. We communicate differently with someone we just met versus someone we’ve known for a long time. Initial interactions with people tend to be more highly scripted and governed by established norms and rules, but when we have an established relational context, we may be able to bend or break social norms and rules more easily. For example, you would likely follow social norms of politeness and attentiveness and might spend the whole day cleaning the house for the first time you invite your new neighbors to visit. Once the neighbors are in your house, you may also make them the center of your attention during their visit. If you end up becoming friends with your neighbors and establishing a relational context, you might not think as much about having everything cleaned and prepared or even giving them your whole attention during later visits.

Communication norms and rules also vary based on the type of relationship people have. For example, there are certain communication rules and norms that apply to a supervisor-supervisee relationship that don’t apply to a brother-sister relationship and vice versa. (Given the managerial/ leadership focus of our textbook and course, such considerations will be explored in detail in several future chapters.)

3. Cultural context includes various aspects of identities such as race, gender, nationality, ethnicity, sexual orientation, class, and ability. It is important for us to understand that whether we are aware of it or not, we all have multiple cultural identities that influence our communication. Typically, people whose identities have been historically marginalized are regularly aware of how their cultural identities influence their communication and how others communicate with them. Conversely, people with identities that are dominant or in the majority may rarely, if ever, think about the role their cultural identities play in their communication.

When cultural context comes to the forefront of a communication encounter, it can be difficult to manage. Since intercultural communication creates uncertainty, it can deter people from communicating across cultures or lead people to view intercultural communication as negative. But if you avoid communicating across cultural identities, you will likely not get more comfortable or competent as a communicator. Intercultural communication has the potential to enrich various aspects of our lives. In order to communicate well within various cultural contexts, it is important to keep an open mind and avoid making assumptions about others’ cultural identities. While you may be able to identify some aspects of the cultural context within a communication encounter, there may also be cultural influences that you can’t see. A competent communicator shouldn’t assume to know all the cultural contexts a person brings to an encounter, since not all cultural identities are visible. As with the other contexts, it requires skills to adapt to shifting contexts, and the best way to develop these skills is through practice and reflection.

Key Takeaways

- Communication models are not complex enough to truly capture all that takes place in a communication encounter, but they can help us examine the various steps in the process in order to better understand our communication and the communication of others.

- The transmission model of communication describes communication as a one-way, linear process in which a sender encodes a message and transmits it through a channel to a receiver who decodes it. The transmission of the message many be disrupted by environmental or semantic noise. This model is usually too simple to capture FtF interactions but can be usefully applied to computer-mediated communication.

- The interaction model of communication describes communication as a two-way process in which participants alternate positions as sender and receiver and generate meaning by sending and receiving feedback within physical and psychological contexts. This model captures the interactive aspects of communication but still doesn’t account for how communication constructs our realities and is influenced by social and cultural contexts.

- The transaction model of communication describes communication as a process in which communicators generate social realities within social, relational, and cultural contexts. This model includes participants who are simultaneously senders and receivers and accounts for how communication constructs our realities, relationships, and communities.

Exercises

- Getting integrated: How might knowing the various components of the communication process help you in your academic life, your professional life, and your civic life?

- What communication situations does the transmission model best represent? The interaction model? The transaction model?

- Use the transaction model of communication to analyze a recent communication encounter you had. Sketch out the communication encounter and make sure to label each part of the model (communicators; message; channel; feedback; and physical, psychological, social, relational, and cultural contexts).

References

Barnlund, D. C. (1970). A transactional model of communication. In Kenneth K. Sereno and C. David Mortensen (Eds.), Foundations of communication theory (83-92). Harper and Row.

Ellis, R. and McClintock, A.. (1990). You take my meaning: Theory into practice in human communication. Edward Arnold.

Schramm, W. (1997). The beginnings of communication study in America. Sage.

Shannon, C. and Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. University of Illinois Press, 1949.