Module 1: Designing for connection

1.4 Learner–instructor connection: Designing courses with personality

Key principles: The importance of presence and humanizing yourself

Online classes are not meant to be like your favorite slow-cooker recipe. They are not “set and forget.” It’s impossible to foster meaningful relationships with that approach.

(Darby & Lang, 2019, p. 87)

Many of the skills you have developed through teaching face-to-face apply in the virtual learning context as well. However, relative to an in-person course, you may need to put in a little more thought, effort, intention, and planning to find ways to close the transactional distance that is inherent online. Spending some time to think carefully about how you will “show up” for your learners in your virtual course is probably one of the most important things you can do. In fact, research shows that the most significant factor in predicting learner success in virtual courses is the instructor presence and interpersonal interactions (Xu & Smith, 2013; Jaggars & Xu, 2016). How you show up in term plays a huge role in bringing your course to life and showing learners that there is a real person who is present and cares about their learning. We will discuss high-impact strategies for fostering and growing your instructor presence in a later module on learner-instructor interaction.

Instructor presence, however, should not be an afterthought or something that you do only after your course is designed and developed. It can be woven throughout the design of your virtual course so that students never feel totally alone in their learning and have an ongoing sense of your instructional presence, guiding them even when you (or another course instructor) are not immediately there with them. For instance, the feeling of presence can come through in how you instruct and guide students through assessments, how you design and present the course content, and in how you plan for and build in learner support.

© Svetikd/E+/Getty Images (instructor); © Svetikd/E+/Getty Images (student) (Copyrighted image. Do not copy, modify, or redistribute).

Quick tips and tricks: Quality not quantity

Building in meaningful opportunities for interaction and connection with your learners does not have to be terribly time consuming. Research shows that it’s not the quantity of interactions with students that predicts learner success, but rather the quality of those interactions. Some simple ways to build in quality/meaningful support for your learners include

- swapping out long synchronous sessions for short check-ins or Q and A sessions with a defined topic—more time on camera does not equal stronger connections; keep session short and specific, so learners know what they are showing up for (see the additional reading on synchronous sessions in the Going deeper section below);

- consider having students submit questions prior to live sessions, allowing you to address areas of concern, or organize sessions strategically around important course milestones (e.g., an upcoming assignment, ahead of a midterm or debriefing after it, etc.);

- prescheduling weekly reminders can help keep learners on track (both in the content they need to review and assessments they need to complete) and give them the sense that you are paying attention—these can be set up ahead of time in most learning management systems (LMSs) by scheduling the date and time of announcements (Hint: schedule announcements to appear at different times of the day, so they don’t feel too automated to students), and/or

- providing learners with whole-class feedback on assessments—if time constraints or class size prevents you from being able to provide individualized feedback, send out an announcement (text or video) that summarizes what learners generally did well and struggled with and how they can improve for the next assessment. Consider posting an A+ assessment (with the learner’s permission and anonymized) that can help learners see how to modify their own approach next time.

Going deeper

The following articles provide primary research evidence of the significant impact instructor presence has on learner outcomes in virtual courses.

- Jaggars, S., & Xu, D. (2016, April). How do online course design features influence student performance? Computers & Education, 95, 270–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.01.014

- Xu, D., & Smith, S. (2013, February). Adaptability to online learning: Differences across types of students and academic subject areas. Teacher’s College, Columbia University. https://eric.ed.gov/?q=Adaptability+to+online+learning%3a+Differences+across+types+of+&id=ED539911

The following is an article that provides some guidance on how to integrate live synchronous sessions into an asynchronous course.

- Lowenthal, P., Dunlap, J., & Snelson, C. (2017). Live synchronous web meetings in asynchronous online courses: Reconceptualizing virtual office hours. Online Learning, 21(4), 177–194. http://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v21i4.1285

Let them “see” you

Your learners are interested in you and the more you can help them get to know you as an individual, the more connected they tend to become to the content, motivated to work hard, and less likely to commit academic integrity violations. There are many ways for your personality to come through in your course, which does not require you to go on camera, if that is not something you are comfortable with.

That does not mean you need to share all the details of your life and you do not need to try to be something or someone you are not. You do not need to try to be funny if you are naturally more serious nor do you need to be especially buttoned-up if that’s not who you are. We are all different, have different teaching personas, and have different levels of comfort around sharing about ourselves, but that shouldn’t keep you from being seen by your students.

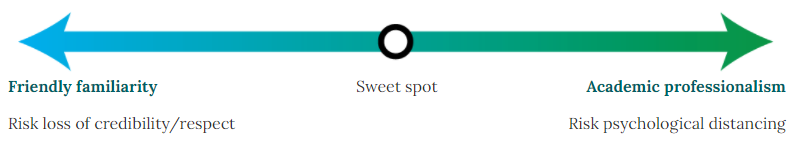

One of the benefits to asynchronous virtual learning, is that you get to carefully craft how you introduce yourself, how you present yourself, and what you share about yourself. The key is to be authentic and find the sweet spot that feels right for you, between friendly familiarity (too far in this direction can impact credibility and professionalism), and academic professionalism (too far this way may keep you feeling far away and unrelatable).

Credit: University of Waterloo

What instructors have to say:

“Being personable does not mean you need to get personal.”

(Prof. James Skidmore, online instructor)

If you want to keep your sharing to the realm of your professional life, that is great, but don’t let that stop you from sharing with your learners what you are passionate about, what drives you in your field, where you may have encountered challenges in your academic or professional life, and how you overcame those challenges. Remember enthusiasm is infectious!

What learners have to say:

“I like the personalization myself … [it] takes away a lot of those “barriers” we get in online courses with our instructors. Puts a person to the name. And those personalities! So much passion for what they do … it’s clear, and motivating. You don’t want to disappoint them.”

(Julie, online learner)

Key principles: Vulnerability and encouraging courageous learning

Asking your learners to be open to learning, allowing themselves to be changed, and to truly connect requires courage, because let’s face it, real and deep learning is hard. Learning is effortful, we risk making mistakes or failing, we bump up against our limitations, and need to persevere through those uncomfortable feelings of uncertainty and confusion in order to get to those beautiful ‘ah-ha’ moments. For many of us (and your learners), prior life experiences, inside and outside the classroom, have taught us that really trying and learning can hurt, especially if learning (and the inevitable mistakes and failures that go along with learning) was ever met with shaming. Shaming is particularly harmful when it comes from someone who had/has power over us, such a parent, boss, or teacher.

Recognizing your power: To help or to harm

As an instructor, your relationship with learners includes an inherent power differential, which can make it especially scary for learners to be open and vulnerable, to reach outside their comfort zone, and really learn. If you want your learners to really show up for your course, whatever that looks like (e.g., engaging in an online discussion or turning on their camera in a synchronous session), it is important to look at how the design of your course, assessments, and how you set up and model interactions with your learners can either

- reinforce feelings of insecurity and shame learners may have around learning or

- give learners the courage, encouragement, and confidence to put in the kind of effort that may make them feel vulnerable, but also make transformational learning possible.

We highly recommend the following resource and the linked video, in particular, as a means of deepening your understanding of the power you hold as an instructor and how you might encourage your learners to really “show up” and how you “show up” for your learners can inspire the kind of courageous and transformation learning that contribute to rewarding teaching and learning.

Going deeper

If you would like to learn more about vulnerability and inspiring courageous learning in your students consider the following resource link and fantastic video from Brené Brown. Brené Brown is an inspiring speaker, instructor, social worker, and researcher the following resources draw on her work on brave and daring leadership and strategies for applying this to the classroom. While some of the resources on this website are targeted at primary and secondary school educators, much of this applies to postsecondary education.

If you have about 30 mins, we highly recommend the following talk by Brené Brown where she discusses the role of vulnerability and courage in learning and the profoundly important role teachers and instructors play in helping or hurting learners.

Transcript for Brené Brown | Daring Classrooms | SXSWedu 2017 available on YouTube.

Credit: Brené Brown, 2017

Strategies in action: Introducing yourself, the course, and welcoming learners

The following strategies foster

- connection: learner–instructor, learner–content;

- significant learning (modelling): application, integration, caring, and human connection; and

- context: all (STEM, Arts, large-class, small-class, novice-learners, advanced-learners)

Welcome announcements and videos

Inviting students into the course at the outset can be done by posting a text-based announcement and/or a welcome video. These can be created ahead of time, but they are often executed right at the start of term by the instructor or course facilitator. For this reason, we cover these strategies and examples in Module 3 Facilitating for Connection in the section called “Instructor Presence During Term.”

Liquid syllabus

A liquid syllabus is another way of providing learners with an orientation to the course, one that is hosted on a public, accessible, mobile-friendly website rather than in an LMS.

The following resource is a quick and helpful overview of what a liquid syllabus is:

Michelle Pacansky-Brock: Liquid Syllabus – An Overview

Here is a link to an example liquid syllabus:

Liquid Syllabus: History of Still Photo

Even if you are not in a position to create a stand-alone site such as this, you may be inspired by the sections of Michelle Pecansky-Brock’s liquid syllabus and maybe be able to create a version of this in your LMS:

- Welcome

- My commitment to you

- How this course works

- My teaching philosophy

- Our pact

- Equity statement

- Week 1 success kit

- Michelle’s six tips for success

- How to get your questions answered

Strategies in action: Providing learners with your professional perspective

Share interesting details on how your research/work connects to course topics, tips on how to work effectively or how you have overcome challenges when you were first learning the discipline, and/or share commentary on emerging trends (discipline-specific or lay-media) and how you interpret them through

- prerecorded videos,

- discussion boards,

- announcements, or

- live sessions.

The following strategies foster

- connection: learner–instructor, learner–content;

- significant learning (modelling): application, integration, caring, and human connection; and

- context: all (STEM, Arts, large class, small class, novice learners, advanced learners)

Your learners DO want to hear what you have to say, and not just read the literature! If you work ‘out in the field’, consider filming an interesting workplace or professional experience using your smartphone (ensure to seek permission before filming). This could be the lab, the office, or outside in urban or rural environments.

Quick tips and tricks: Videos that are not perfect, but are human

If you are creating videos, they do not need to be polished, just grab your smart phone and start recording. Often these short impromptu videos feel more authentic and personable—more human than a high production video.

The following video is longer and more elaborate than the short videos we are talking about in this section, but the beginning of this video helps to illustrate how real and engaging a lower quality recording can be. It’s not perfect, the camera is a little wobbly, the instructor recording is speaking to the person doing the demo and laughs, which can help the viewer feel more connected and like they are watching real people. Then the instructor turns the camera on himself and talks right to you.

Transcript for Can Silence Actually Drive You Crazy? available on YouTube.

Credit: Veritasium, 2014

Strategies in action: Modelling and Inspiring connections with your learners

These following strategies foster

- connection: Learner–instructor, learner-learner, learner-content;

- significant learning: Foundational knowledge, Application, Integration, Learning to Learn, Caring, and Human Connection; and

- context: All (STEM, Arts, large class, small class, novice learners, advanced learners).

Digital stories

Sharing with learners why you are interested in a topic and/or showing them how topics relate to personally relevant or real-world issues can really help spark their own interest and connection with you, each other, and content. Digital stories is a strategy that starts with the instructor creating a short video that highlights a personal or real-world connection to a course topic and then inviting learners to create their own digital story. These can be shared in the class by posting them in a discussion forum in your LMS. Keep this activity low-stakes (not heavily graded), to take some of the pressure to perform off and allow students to really explore and be creative!

Show rather than tell: Examples, demonstrations, and clarifying expectations

Providing learners with explicit instructions is often not sufficient for them to really understand the nuances of many academic and discipline-specific skills, such as academic writing, discourse, debate, or critical thinking. Providing learners with applied examples is an important way to model these critical or more nuanced skills which many learners struggle with.

When we simply tell learners to write a paper or consider questions and post to an online discussion, we are assuming that learners already know how to engage in this type of academic behaviour. However, even learners in higher-level courses struggle with these skills, and some have never had the opportunity to try it out, get feedback on, or observe well-executed examples. Modelling is critical for all those academic behaviours and learning outcomes that really go beyond fact memorization. Below are a couple of strategies that can make a huge difference in the quality of learner-learner interactions and performance on assessments.

Assessment expectations

Provide learners with examples of exemplar assessments (e.g., writing samples, efficient code, or effective ways of solving a problem in your discipline) before learners start to work through their assessments. Annotating an example of a learner assessment, highlighting what the learner did, why it worked, or how it could be improved, helps to model the kind of self-monitoring and metacognition that is required for evaluating one’s own work. Learners often get this feedback and modelling when it’s too late to impact their performance in the course (e.g., a final paper).

Discussion forum expectations

If your course has a discussion forum, but there is little guidance around how learners should interact, write out some guidelines around learner conduct in online discussions:

- Provide some examples of what a meaningful discussion contribution would look like.

- Outline the importance of professional academic discourse (explain what this means) and use of respectful language.

- What are the consequences if someone violates these guidelines?

- Provide some online discussion tips for students.

Pop into your learners’ online discussions, providing occasional comments that help move discussions forward and modelling academic discourse and the types of skills you hope learners will develop (e.g., productive debate, critical thinking, and problem-solving).

Going deeper

The following is a resource that provides some good examples of discussion protocols and designing seminar courses:

See one, do one, teach one

When designing your assessments, you might consider the see one, do one, teach one model, where

- you demonstrate a skill or you provide examples of either your own work or the work of other learners (with their permission);

- learners experiment and try themselves and possibly submit an example of their work as a low-stakes assessment for feedback; and

- learners teach that skill or information to other learners, as either a whole class activity or in smaller groups. This could be done in short video presentations or could be done through a discussion forum, where learners take the lead in facilitating on online discussion forum (if the class is large, break learners into smaller groups of about 5–10 learners).

Quick tips and tricks: Accessing institutional supports

Explore what central institutional resources are available to you and your learners at your institution to help your learners build soft skills. Some academic and student support units may be available to run a custom live or recorded webinar for the needs of the course. This can be an interesting way to teach soft skills with little additional resources but big impact.

- Does your institution have a writing centre that can provide a workshop?

- Does your institution have a librarian who can provide guidance on how to conduct research for large project/paper in your discipline?

- Does your institution have an accessibility services representative who can talk about design considerations for your course to help ensure your course is accessible?

- Does your institution have a student success office or wellness centre that has resource you can share with your students to get them started on the right foot and know where to go if they need help that goes beyond your course?

Strategies in action: Creating opportunities for feedback on learning

The following strategies foster

- connection: learner–instructor, learner–content;

- significant learning: learning to learn; and

- context: all (STEM, Arts, large class, small class, novice learners, advanced learners).

Guidance on providing learner support

The most important factor for giving learners a sense of being supported is demonstrating how and when they can get help when they need it. It is important that support/help is

- accessible to all learners: This means not just being available at one time or through a single modality, such as video conferencing. Try to make yourself available through a variety of channels, such as email, discussion forums, and online office hours;

- timely: The recommendation is email responses within 24 hours, Monday to Friday. You may have a different time frame or there may be days where you won’t be able to respond to learners. If so, make sure that those days or times when you are less available are clear to learners so they can plan around your schedule. Keep in mind that many learners do their learning at night and/or on the weekend and may be in different time zones; and

- setting clear policies and expectations: Ensure you clearly communicate all course assignment deadlines (and significant milestones), turnaround time on receiving feedback/grades, and a clear and rationalized late policy. This way learners can plan their whole semester from day one according to their other responsibilities and know what to do if they run into problems. This helps build mutual respect and accountability for the upcoming learning journey which may inevitably have bumps and challenges along the way.

(Darby & Lang, 2019, p. 89)

Scaffolded assignments

One earth, one health: Advocacy brief assessment

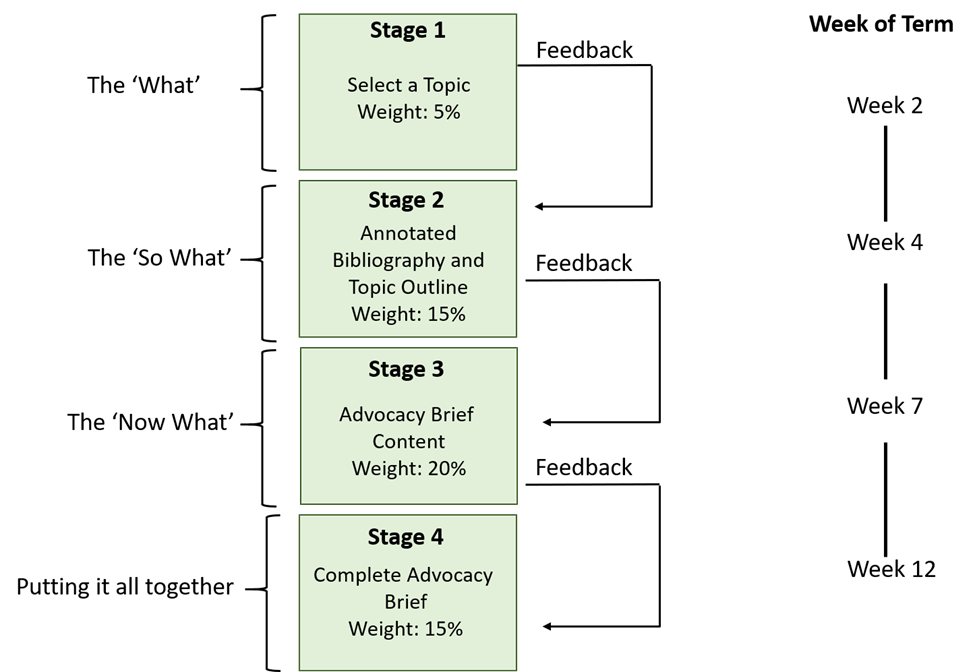

In the following example, the term assignment is scaffolded over Weeks 2 to 12 with four stages. Each stage of the assignment includes a student submission for evaluation as well as feedback from the instructor. This scaffolded approach to this assignment provides opportunities for students to develop skills in analysis and comprehension of course material, but also to respond and apply feedback to subsequent stages of the assignment. The first three stages and the provided feedback are collectively applied to the final submission of a complete advocacy brief in Stage 4.

Assignment: A climate change plan for a real-world community

For this Geography and Environmental Management group assignment students prepare a climate change plan for a real-world community that does not yet have a plan in place through a scaffolded process.

Stages include

- team contract,

- selection of case study community,

- outline of proposal and references,

- proposal and references, and

- presentation and discussion.

Climate Change Plan Assignment Example (PDF)

Credit: Dr. Mark Seasons, School of Planning, University of Waterloo

Rubrics

Designing grading rubrics for each of your assessments is one of the most important strategies for communicating to learners what your expectations are and transparency around how they will be assessed.

Philosophy – Critical thinking: Personal reflection assignment rubric

This rubric is for an assignment on a personal reflection on fallacies and asks students to reflect on two situations where they used faulty reasoning. They are asked to address five points:

- Describe a situation where you have used a fallacy.

- Identify the fallacy that you used.

- Explain why this is an example of that fallacy.

- Correct your reasoning.

- Include reasonable strategies for avoiding this fallacy in the future.

Philosophy Rubric Example (PDF)

Credit: Shannon Buckley, General Arts and Science, Interdisciplinary Studies, Conestoga College

Going deeper

If you are interested in learning more about designing really useful rubrics, the VALUE Rubrics is a great resource for creating rubrics that assess intellectual and practical skills, personal and social responsibility, and integrative and applied learning. You will want to ensure that your rubrics are well aligned with the significant learning goals of the course, the LOs you shared with learners, and of course the expectations you outline in the assignment instructions.

Strategies in action: Seeking learner feedback

These following strategies foster

- connection: Learner–instructor and

- context: all (STEM, Arts, large class, small class, novice learners, advanced learners).

Getting to know your learners with surveys

Surveys and polls can be a quick and easy way to get a sense of who is in your course. Recall in a previous activity, Reflect and Apply: Getting to Know your Learners, we included some questions about who your learners are, which might be helpful as a starting place for creating your own survey questions to get to know students. Below are some more examples and guidance.

Personally identified surveys

Nonanonymous surveys can be helpful to get to know individuals and can be very useful for sorting learners into intentional groups. You may choose to assign groups based on different factors, but one of the most helpful ways to group is by location/time zone, as this will make working in teams much easier.

Anonymous surveys

Anonymous surveys can be helpful in collecting more personal and honest information from learners without requiring them to self-disclose their identities or be concerned that they will be singled out, judged, or evaluated for what they have shared. This will give you an overview of who is in the class and the diversity of perspectives and goals.

Here is an example survey you might use as a starting place, from Michelle Pacanksey-Brock: Getting to Know You Survey

Closing the loop: Sharing survey results

Learners often enjoy and benefit from seeing how their classmates responded to surveys and seeing the diversity in the class. Consider sharing anonymous aggregate results from the introduction survey as a course announcement. This also helps to close the communication loop, shows your learners that you have done something constructive with the information they shared, and provides learners with something in return for the time they spent filling out the survey.

Teaching 3-2-1

Get feedback from learners on their learning and foster learner reflection. An excellent way to foster learner reflection and to receive feedback from learners on their learning progress and potential bottlenecks. Learners write about

- three (3) things they learned in the week’s content;

- two (2) things they found particularly interesting, and

- one (1) question they need clarifying.

Reflect and apply: Creating the conditions for courageous learning

Identify a couple of strategies you can apply to help create a safe environment in your virtual course that encourages learners to be open, to make mistakes, and engage in courageous learning.

How to complete this activity and save your work:

Type your response to the questions in the box below. Your answers will be saved as you move forward to the next question (note: your answers will not be saved if you navigate away from this page). Your responses are private and cannot be seen by anyone else.

When you complete the below activity and wish to download your responses or if you prefer to work in a Word document offline, please follow the steps below:

- Navigate through all tabs or jump ahead by selecting the “Export” tab in the left-hand navigation.

- Hit the “Export document” button.

- Hit the “Export” button in the top right navigation.

To delete your answers simply refresh the page or move to the next page in this course.

Going deeper

You can find more on humanizing learning from Michelle Pacansky-Brock at the following links:

References and credits

Darby, F., & Lang, J. M. (2019). Small teaching online: Applying learning science in online classes. John Wiley & Sons.

Jaggars, S. & Xu, D. (2016). How do online course design features influence student performance? Computers & Education, 95, 270–284.

Xu, D., & Smith, S. (2013). Adaptability to online learning: Differences across types of students and academic subject areas. Teacher’s College, Columbia University. https://eric.ed.gov/?q=Adaptability+to+online+learning%3a+Differences+across+types+of+&id=ED539911

The “Strategies in Action: Welcoming Your Learners” section of this page is derived from original Fostering Engagement: Facilitating Courses in Higher Education – 3.c Strategies for building student-facilitator interaction by K.E. Wilson and D. Opperwall. The original work is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, except where otherwise noted. This derivative work, “Strategies in Action: Welcoming Your Learners” has been adapted from the original through modification of text, images, and headings and retains the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.