Module 1: Designing for connection

1.5 Learner–content connection: Designing valuable learning experiences

Key principles: Course content design for humans

Content is at the heart of learning. Learners come to postsecondary institutions to discover new information, identify important problems and their solutions, encounter new ideas, and learn new processes. In short, engaging with content is nearly always a learner’s primary goal.

Learners interact with content any time they encounter a new fact, idea, theory, or principle presented to them by another person in a course, whether by reading, watching, listening, or viewing something. In his seminal work on interaction in distance education, Michael Moore (1989) locates learner–content interaction at the heart of all learning experiences.

Without [learner–content interaction] there cannot be education, since it is the process of intellectually interacting with content that results in changes in the learner’s understanding, the learner’s perspective, or the cognitive structures of the learner’s mind.

Moore (1989)

Identifying learner–content interactions

Let’s begin by thinking about the types of learner–content interaction that will take place in your virtual course. Not all virtual courses deliver content in the same way, and most courses use a variety of methods for content delivery. Some common learner-content interactions for virtual courses include

- assigned readings (textbooks, articles, primary sources, etc.);

- written lecture materials or transcripts of lectures;

- illustrative images;

- charts and graphs (often static, but may be animated);

- video or audio lectures;

- narrated PowerPoint presentations;

- embedded or linked multimedia content (such as films, YouTube videos, podcasts, etc.);

- links to popular media, current news events, or blogs;

- research assignments (in which learners curate content themselves); and

- content sharing between learners (such as in a discussion, class wiki, or group project).

The key to designing virtual learning materials and virtual course content in a way that really engages students and fosters those connections that lead to significant learning is to understand how humans engage with virtual materials, what helps them and guides them into these materials, and what hinders them and pushes them away. In other words, virtual content and activities will be most effective if they are grounded in knowledge of how humans function in online contexts, how they learn, what motivates learners to really engage, and what frustrates learners and leads them to shut them down. We can turn to two key areas in human research to ground our design strategies in evidence:

- User experience (UX) research tells us how humans interact with web interfaces.

- Human psychological research tells us how humans attend to and process information, remember information, and learn.

A framework developed by the Centre for Extended Learning at the University of Waterloo provides guidance on how to create quality learning materials that foster learner-content connection and significant learning.

© fizkes/iStock/Getty Images (left); marrio31/E+/Getty Images (right) (Copyrighted image. Do not copy, modify, or redistribute).

Key principles: Creating valuable learner–content interactions

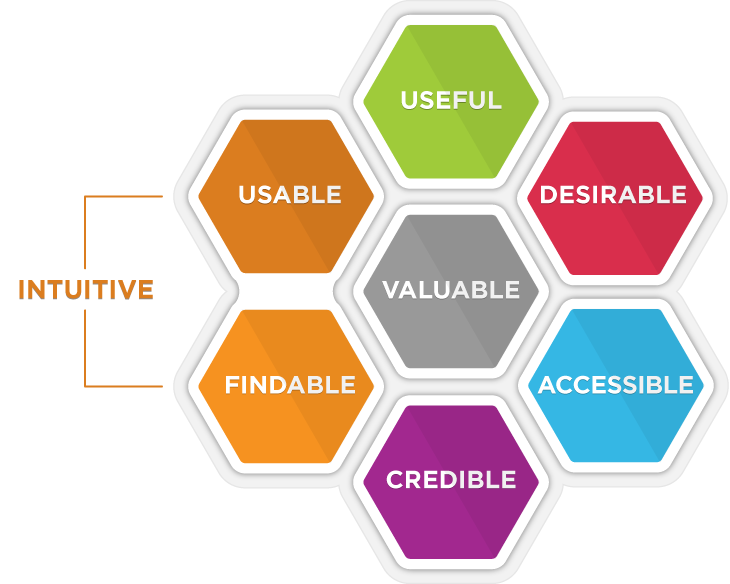

The User Experience Design for Learning (UXDL) Honeycomb is a framework that provides a great foundation in key principles of virtual content and activities design. This framework was adapted, with permission, from Peter Morville’s UX Honeycomb. The UX Honeycomb provides principles of UX design for the web and the UXDL adapts this framework to the context of learning online, grounding each principle in psychological research on human information processing, memory, and learning.

Since I created the User Experience Honeycomb in 2004, it has been adopted and adapted by people and organizations all over the world. But the [UXDL] framework that CEL has developed for creating valuable online learning experiences is my favorite application yet.

Peter Morville, UXDL Honeycomb

Each cell of the UXDL framework provides specific and practical guidance for post-secondary educators who want to create virtual learning experiences that take their learners and the medium of virtual learning into consideration, creating Desirable, Useful, Accessible, Credible, and Intuitive (Findable and Usable) learning experiences. Each of these principles are aligned with how humans learn and process information, helping to leverage the affordance of the virtual environment and mitigate limitations.

Credit: University of Waterloo, UXDL Honeycomb. Adapted with permission from Peter Morville.

Going deeper

The UXDL framework has been validated with undergraduate learners at the University of Waterloo in a research study that included 800 survey participants and over 100 hrs of user experience testing sessions using courses across the disciplines (arts and humanities, social science, and STEM courses). The research reveals that learners value online learning experiences that are aligned with the UXDL framework. To learn more about what learners have to say you can read this primary research:

- Troop, M., White, D., Wilson, K.E., & Zeni, P. (2020). The user experience design for learning (UXDL) framework: The undergraduate perspective. The Canadian Journal of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2020.3.8328

Designing courses that are desirable

Visceral Design

(Beauty)

Behavioural Design

(Function)

Reflective Design

(Reflection)

Human Design

(Connection)

UXDL Honeycomb

The Desirable cell of the UXDL framework captures the importance of creating content that can evoke the kind of affective (emotional) responses from your learners that are conducive to significant learning and demonstrates to your learners that you also care about their learning and experiences in your course. When we talk about the affective dimension of learning we are not just referring to basic emotions (joy, sadness, anger, fear, etc.,) but are also referring to important cognitive emotions, such as curiosity, interest, surprise, and motivation, as well as more negative emotions such as confusion, frustration, embarrassment, or even shame. We want to foster those positive learning emotions and mitigate some of those negative cognitive emotions.

Creating a desirable course is not simply about making your course look pretty, rather it is about taking into consideration the elements in your course design that influence the emotions that modulate significant learning. While it may be easier to see the connection between affective design and how that design may impact significant learning in the caring, integration, and human dimensions, a course designed with these desirable principles in mind can impact learning in each of the other dimensions through the interest, motivation, learner buy-in, relevance realization, and reflection they facilitate.

The Desirable cell emphasizes the important role of the following strategies on virtual learner experience:

- Good visceral design and the role of aesthetic appeal on learner experience and buy-in.

- Good behavioural design and the impact of how your course functions on learners.

- Good reflective design and how design can lead learners towards deeper understanding, self-relevance, and reflection.

- Good human design that highlights the critical role that humanizing learning plays in design, which much of this course is about.

Some negatively perceived cognitive emotions can be helpful in small doses and are a natural part of learning, such as mild confusion, as that is often what precedes a real shift in understanding, but we never want a learner to feel shame around their efforts to learn. The strategies encompassed by the Desirable cell are part of helping learners care (a significant goal of learning) about the content. Emotions have a cool way of changing how we think and process information. Implementing a couple key strategies to create desirable learning experiences in content and assessment design can bolster those helpful cognitive emotions in your course and can go a long way to improving learner experiences and outcomes in your course.

Going deeper

To learn more about these Desirable strategies view the following page, which provides a brief description of each strategy with some examples.

Designing courses that are useful

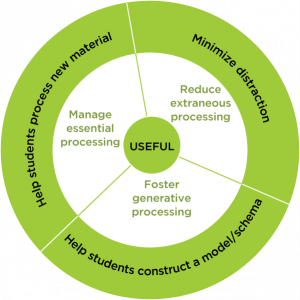

The Useful cell of the UXDL honeycomb emphasizes the importance of and provides guidance on how to

- avoid cognitive overload in how you present information to your learners;

- help learners select, organize, and integrate information to construct meaning and enhance retention;

- reduce extraneous processing so learners do not need to overcome unnecessary distractions and are guided through the content to what is most relevant;

- manage essential processing so that learners are not unnecessarily dividing their attention and information is presented in manageable and meaningful chunks; and

- foster generative processing by presenting content in a way that helps learners organize and integrate information within the course and with their prior knowledge and provides them with valuable opportunities to test and get feedback on their learning.

Going deeper

To learn more about these Useful strategies view the following page, which provides a brief description of each strategy and examples.

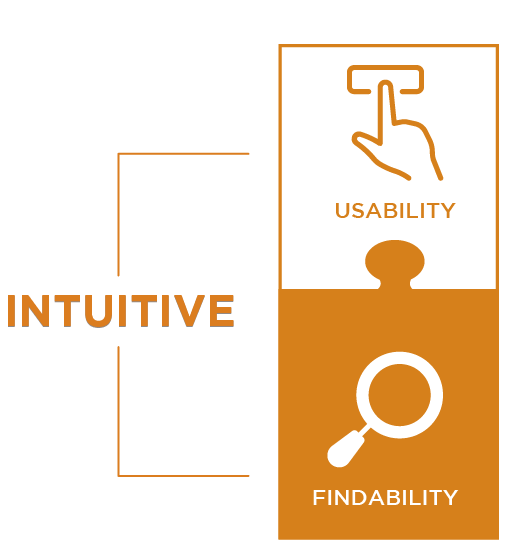

Designing courses that are intuitive

Courses that are difficult to navigate or are not intuitive tend to evoke unhelpful negative emotions and lead to frustration as learners grapple with navigating the course rather than focusing on the content and activities. This cell in the UXDL framework is composed of two cells that are closely yoked, Usability and Findability.

- Findability refers to course navigation, content and activities that are easy to find.

- Usability refers to how easy it is to use, engage with or complete content, activities, or assignments once they are found.

When we design a course that is intuitive (where things are easy to find and easy to use), we remove some of the unnecessary negative emotions and effort that learners need to put into finding and using our course materials, so they can focus on the learning.

Going deeper

To learn more about these Intuitive design strategies view the following page, which provides a brief description of some strategies and an outline of how you can get feedback on your course design by conducting your own UX testing with learners to identify where they may struggle.

Three ways to get feedback on the intuitiveness (findability/usability) of your course:

- If you would like to do your own UX testing with a sample of learners (5 is recommended) here are some resources to help you set that up:

Wondering about why 5 UX participants is the magic number? This article explains:

- If you have TA support, you could ask your TAs to navigate the course and let you know if anything was unclear or confusing, where they got lost or struggled to find something, and what is working well and what may not be working as intended. Create a find and seek activity (list of tasks that will take them all through the course looking for important information), which will also help to serve as the TAs’ orientation to your course.

- Instructor peer-review each other’s courses for UX. With a colleague with whom you feel comfortable sharing your virtual course, test the UX of each other’s course and provide constructive feedback to each other. This has the added benefit of putting you in the role of the learner, which can bring fresh insight into the learner experience that may help you further improve the navigation in your own course.

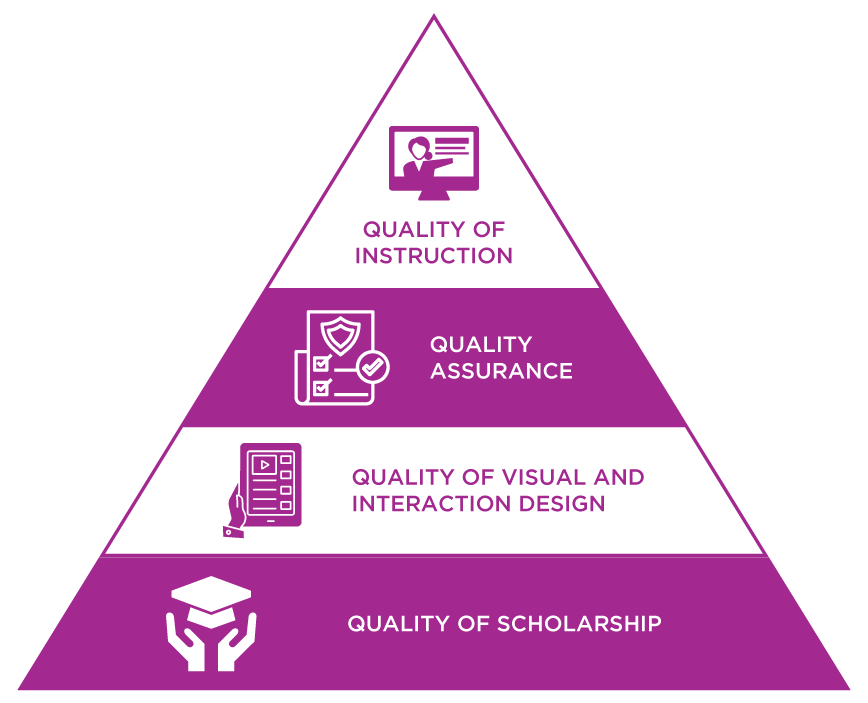

Designing courses that are credible

Credibility really comes through all the facets of a quality virtual course, from how you as an instructor present yourself and support learners, to the intuitiveness of the course, to how it looks and feels, to whether materials are presented in a useful way for learners. Credibility is about building rapport, trust, and a relationship in which learners see you as an expert in the field and trust you as a teacher.

Credibility captures strategies that demonstrate

- quality of scholarship through how you have designed and authored the course and models the kind of scholarship you expect learners to demonstrate in their learning, such as proper citation style;

- quality of visual and interaction design through pleasant visual design that gives the sense that the course is current, up-to-date, relevant, and shows learners that you care. Learners frequently make the association between a pleasant visual design and credibility of the material and reputation of the instructor. A simple, clean design can go a long way;

- quality of assurance one that is free of grammatical and spelling errors, uses software that is set up properly and works efficiently, and is accessible for all learners. Prompt in-term technical support contributes to a quality learning experience for learners studying online; and

- quality of instruction through clearly articulating to learners your expectations of them and how they will be assessed (e.g., through learning outcomes and well-aligned content, activities, and assessments) and being available for and engaging with your learners throughout the term.

Going deeper

To learn more about these Credible design strategies view the following page:

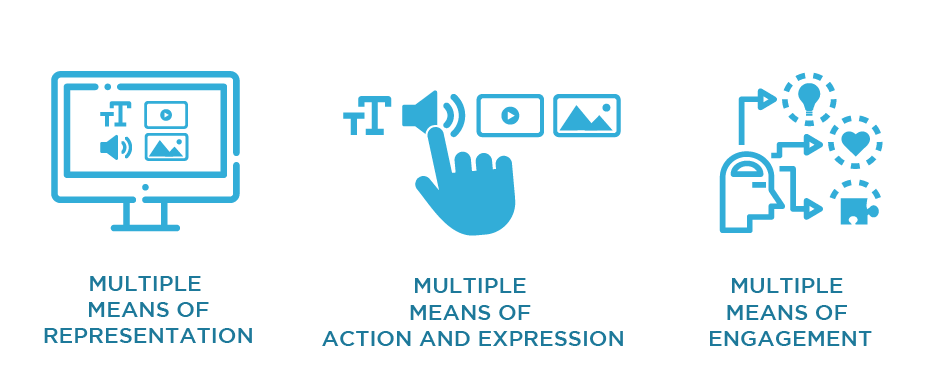

Designing courses that are accessible

This cell of the UXDL framework provides a brief overview of the importance of creating courses that are accessible for all learners. Access is probably one of the most important factors to consider in designing your course, as without access learners are isolated and excluded from learning. Further, it is not just learners who have self-identified as having a disability that benefit from strategies that make a course more universally accessible. As a starting point, the Accessible cell of the UXDL framework provides some guidance on making a course more accessible, for example you can

- provide multiple means of representation or present content and information in different ways,

- provide multiple means of action and expression or allow learners to express what they know in different ways, and

- provide multiple means of engagement or offer options to stimulate interest and motivate learners.

In the next module of this course we are going to talk more about accessibility and the idea of designing your course in a way that makes it more universally accessible to more people known as Universal Design for Learning.

Going deeper

To learn more about these Accessible strategies view the following page, which provides a brief description of each strategy and examples.

Strategies in action: Examples of UXDL applied to virtual courses

The following strategies foster

- connection: learner-content;

- significant learning: foundational knowledge, integration, care, learning to learn; and

- context: all virtual courses, across disciplines and class sizes

Creating a valuable learning environment with limited resources

Even if you have limited time and resources at hand and you are working with a text-based Learning Management System (LMS) as your main content delivery method, there are many simple, yet effective ways to create an effective, humanized learning experience for your learners. Here are some tips to enhance the UXDL of simple, text-based LMS courses:

- Complete your LMS profile: Upload a profile picture to the system and complete any other default information so your presence in the online space is solidified.

- Present a credible start to the course: Ensure that by the first day of class you have uploaded your syllabus, a timeline of activities and assessments for the whole semester (all module/content open/start dates, assignment deadlines, etc.), welcome announcement for your course (with photo and/or video), and the first week’s material, including all assignment descriptions (rubrics can be released later if needed). Even if you still have much work to prepare for the rest of the semester, the learner can gain confidence in what the expectations are from them and get comfortable with your style of teaching and content presentation. Consider creating a liquid syllabus, as was demonstrated in an earlier section in this module.

- Create the skeleton of the rest of the course: Decide how you will release subsequent content and create ‘shells’ for this content (if not yet created or updated) by the first day of the course, setting to release at a certain date; this way (a) you already have logically thought through the entirety of the virtual presentation of your materials, and (b) learners can anticipate when they will receive access to future content as the release date (but not the content) will be visible to them.

- Help learners navigate and understand how course information (concepts and knowledge) is structured: Break your content down into short meaningful chunks, making use of

- hierarchical headings (learners can better navigate and find concepts and understand how concepts are scaffolded and/or related),

- bolding and indentation/tabs (ensure important information stands out), and

- bulleted and numbered lists (help to break up text and depict concepts in easy-to-remember format).

- Be consistent: Even if all you do is present some short text, embed a short overview video/presentation/mini lecture, and post a couple articles/resources in your LMS as the core of the learning content for each of your modules, present it in a consistently formatted style, paying attention how you name links and files. Simple can be great, as long as there is attention to detail!

- Avoid duplication of critical information (mistakes happen). For example, only listing due dates in one place (i.e., the course schedule) makes it easier for you to make changes, means the learner only needs to check one location to find that important information, and they will not second guess it or run into conflicting information elsewhere in the course.

- Provide a way for learners to interact with each other in the first week, whether through a discussion board or a collaborative application (more on this in the next section of this module).

- Consider creating summary graphics: Even if you don’t have time/resources to develop a highly interactive course module/page, could you increase the significant learning in your course by creating word maps/flow charts/frameworks to present to learners with each module of content, to help them connect various ideas and concepts together? These types of image can be easily constructed in common software like Microsoft PowerPoint and saved as images.

Credit: Dr. Paul Wehr, Department of Psychology, and Centre for Extended Learning, University of Waterloo

These strategies help with

- credibility: The learners can easily appreciate the care you put in to prepare the learning space for them, as they will be able to quickly find all the information they need for the first week of the course, and be able to understand and predict the expectations of them for the rest of the course; and

- findability and usability: Even if the page is still in progress, a framework is presented of how the virtual space will “grow” with time, bringing confidence and assurances to the learner. Pages that are well structured, with clear headings help the learner navigate the content and find concepts.

Quick tips and tricks: Limited resources, keep it simple

The remainder of the examples in this section are courses that engaged collaborative teams in their creation (e.g., the instructor(s) with institutional/departmental multimedia professionals, instructional designers, coders, etc.) however, the principles highlighted in these examples can be achieved even if you have few resources to enhance the value and positive impact of

- text-based courses in an LMS,

- slides,

- instructor notes, and

- assessment design and instructions.

Civil engineering videos for a blended course

The University of Waterloo Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering’s Wayne Brodland and Rania Al-Hammoud have developed a series of educational videos that can be used in blended or fully online virtual courses. These videos are created to augment key experiential learning activities that learners would undertake in Brodland’s and Al-Hammoud’s Intro to Civil Engineering course. In-class time constraints mean that learners are not able to complete all of these hands-on learning activities. With this suite of videos, learners can vicariously experience each of Professor Brodland’s hands-on learning models through a blended learning approach.

Here the creators made careful use of

- segmenting: this is achieved by breaking content into small, easily digestible segments (~5–10 mins), which gives learners the key information in meaningful chunks and also gives them a natural pause that helps them regulate their attention;

- signalling: this is done with words and highlighting on-screen that directs the eye to relevant points in the video;

- visceral, behavioural, reflective, and human design: these principles are modeled here through the carefully created and higher production value videos, with relatable examples that encourage learners to recall moments where they have experienced the forces described in the video, so as to build a more intuitive sense of how these forces work in the world and are more than just equations; and

- credibility: The production quality of the course materials and the modeling of academic standards, such as proper use of citations lend credibility to these videos.

Transcript for Engineering Models Channel — Introduction available on YouTube.

(Engineering Models Channel, 2018)

This video provided a brief introduction to all the different instructional videos in this Youtube channel. To see these UXDL principles in action consider watching some of these Engineering Models videos highlighted in the introduction video in full. If you teach Civil Engineering or topics related to these videos, the creator, Professor Wayne Brodland also has designed activities, as well as instructions on how to create the physical models in the videos if you would like to use them for in-class activities.

Mechanics Models (additional teaching materials and resources)

Math course example

This module was created by the Mathematics Department at the University of Waterloo. This example demonstrates

- segmenting: Videos are broken into small chunks and each video is subdivided further;

- accessibility: There is a text alternative for learners that don’t learn best from video; and

- foster generative processing through feedback on learning: This course provides valuable self-assessment quizzes that provide learners with not only feedback on their learning, but help them understand where they are going wrong.

Introductory video on the scientific method

The Scientific Method example below is an open resource describing how the scientific method works by using global climate change as an example. It uses the following UXDL principles to help learners select, organize, and integrate relevant information:

- Multimedia: The resource includes a combination of text, images, video, and interaction, which helps learners to attend to and stay focused on the material but also to learn it efficiently, as they organize and integrate the visual and verbal representations and actively engage in meaning-making;

- Coherence: Content is well-structured and uses lots of white space; images do a great job of depicting spatial relationships and are used to enhance understanding or otherwise contribute to the experience of reading the text;

- Segmenting: Text-based content is broken into easily readable chunks with images, video, and interactions interspersed throughout to aid understanding;

- Signalling: This is done with icons and call-out boxes; and

- Credibility: The production quality of the video in particular, and the proper use of citations lend credibility to the resource.

Credit: Keith Delaney, Faculty of Earth and Environmental Sciences, and Centre for Extended Learning, University of Waterloo

Chemistry for engineers module

This example course is an open course on Chemistry for Engineers, which uses the following UXDL principles to help learners select, organize, and integrate relevant information:

- Multimedia: organizational visuals paired with text help learners construct a schema of the concepts introduced, actively engaging them in meaning-making

- Coherence: content is well-structured and uses lots of white space; images are used to depict spatial relationships and to put human faces on the theories introduced

- Segmenting: text-based content is broken into easily readable chunks with images interspersed to aid understanding

- Signalling: done here with the theorist call-out box and the highlighted words inside the box

- Reflection and testing effect: learners have the opportunity to get feedback on their learning through concept checks

Chemistry for Engineers: 2. States of Matter

Credit: Jason Grove, Department of Engineering, and Centre for Extended Learning, University of Waterloo

Sustainable cities module

The following open module, on Sustainable Cities: Adding an African Perspective is another good example of several UXDL principles.

The following video from this course provides an example of the modality principle. The modality principle involves pairing spoken words with visuals to reduce cognitive load and facilitate learning of essential but cognitively complex material.

Transcript for Population Projections available on YouTube.

Credit: Nadine Ibrahim, Department of Engineering, and Centre for Extended Learning, University of Waterloo

Strategies in action: Authentic and personally meaningful assessments

This strategy fosters

- connection: learner–content;

- significant learning: foundational knowledge, application, integration, care, human dimension; and

- context: across disciplines and class sizes (group assignment modifications for larger classes).

Individual advocacy assignment

Sometimes it can be difficult to bring personal relevance to “hard science” courses. One way to counter this is to think of how learners can advocate for a cause or issue related to the course materials. This can bring in social, environmental, ethical, political, or other dimensions which may not be directly covered by core course content.

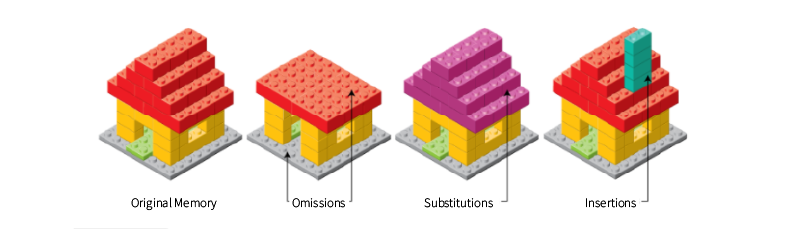

In this example, learners in a fourth-year undergraduate neuroscience course have the opportunity to understand the personal and situational challenges and experiences of individuals living with learning and memory disorders. The assignment requires students to study the clinical characteristics of the disorder, treatment options, and community support program available to support the integration of these individuals into society.

There are two paths learners can take with the assignment:

- A more advocacy-focused approach involving interviewing a patient with the disorder (or their caregiver) and writing an individual advocacy report.

- An approach more focused on a scholarly review of the disorder and a review of treatment and community resources available to patients with that disorder in general.

Skills developed in this assignment:

- Scholarship and caring: students exercise their ability to use scholarly research to review the scientific understanding of this disorder, and have developed their capacity for empathy and advocacy after learning and considering the lived experience of individuals with the disorder.

- Communication: students practice writing with different audiences in mind – their disorder review will be geared towards peers or academics, while the advocacy component should be geared to a lay person in the community.

- Learning to learn: students provide a short critical review of another student’s report on a different disorder, giving them an opportunity to learn about another disorder and practice their peer review skills.

The learners are provided with

- a detailed assignment description that ensures both paths of the assignment remained equivalent in amount of work expected from the learner;

- support and connections to local organizations should they need help finding an interviewee;

- a date mid-way in the semester to declare their topic and interview plan (if applicable) for approval;

- a template for a basic letter of Information and consent form that learners who will be interviewing individuals could use; and

- a grading rubric used to guide peer-review and evaluation by the instructor.

What instructors have to say:

“The Disorder/Advocacy assignment is the capstone assignment of the course. After being exposed the neuroscience of learning and memory and various ethical issues throughout the modules, students now do a deep dive into a learning and memory disorder of their choice and consider the ethical and advocacy challenges around how individuals with that disorder are cared for and integrated into society. Many students love this assignment and feel that it really prepares them for their future in healthcare. For those who chose to do the interview with an affected individual, it can be a transformational experience. Their eyes are opened to the bigger picture of medicine – not just knowing how organs work and how medicines treat illness – but the challenge of treating the whole person within the context they live. I have received incredible, very moving, and sometimes publication-worthy papers from my top students. As an instructor, reading these has been the highlight of my teaching career.”

(Dr. Susan Boehnke, online instructor)

Credit: Dr. Susan Boehnke, Centre for Neuroscience Studies, Queen’s University.

Strategies in action: Activities and assignments that build learner–content connection

The K. Patricia Cross Academy offers a huge number of example activities and assessments that you can use to help increase student engagement across a wide variety of courses and settings. Below you will find links to a few examples that we think you will find valuable when designing your course (please scroll down to find videos on how to adapt each technique to the online environment). Each of these examples helps to bridge the distance between students and course content by employing principles like

- signalling relevance by connecting course content to current events, or by signalling the significance of readings and other content through guided exercises;

- encouraging collaboration between students by creating opportunities for students to learn content together in active ways that go beyond the traditional web forum; and

- encouraging metacognition through reflection on content and sharing reflections so that students have a chance to stop and think about what they are learning and why, and to share these reflections for the benefit of others.

The following strategies foster

- connection: learner–content;

- significant learning: foundational knowledge, integration, application, caring, learning to learn; and

- context: all class sizes and disciplines.

Contemporary issues journal

The contemporary issues journal is an activity in which students take time to think about the connections between what they are learning and a contemporary issue or current events.

Team Jeopardy

Team Jeopardy is a synchronous activity (which can be done online with video conferencing) that allows students to learn content actively together with a jeopardy-style quiz game.

Three-minute messages activity

Three-minute messages is an activity in which students distill key concepts and share their presentations with one another to help clarify difficult ideas for themselves and share the benefit of such clarifications.

Active reading documents activity

Active reading documents is a guided reading activity that allows you to infuse some instructor presence into student reading time through guided reading activities that can be completed asynchronously.

Guided notes activity

Guided notes is an activity that creates further structure surrounding lecture content so that students can more efficiently process and assimilate new information.

Lecture engagement log

Lecture engagement log is an activity that encourages metacognition among students as they engage with lecture materials and other content, and provides further instructor presence especially during asynchronous lecture delivery.

Online resource scavenger hunt activity

Online resource scavenger hunt is an activity that helps learners engage with course content while providing them with the opportunity to practice performing the difficult and important task of navigating online resources to find relevant and reliable information/sources online.

Reflect and apply: Designing with the learner in mind

Identify some implementable design strategies from the User Experience for Design for Learning Framework that you can apply in your own course to help learners better connect with content, activities, and assignments. Use the table below to

- identify a strategy for each cell in the UXDL framework that you could implement at some point;

- identify the specific strategy that interests you;

- outline for yourself some ideas about how or where you’ll implement it; and

- help you select strategies that will have the highest impact in your course; identify how that strategy may align or support some of your course goals and/or help learners prepare for assessments and/or how this may help address one of the challenges you or your learners have experienced in your course (or you are worried about experiencing).

| UXDL Cell (Desirable, Useful, Intuitive, Accessible, Credible) | Specific principle in this UXDL Cell | Approach/Strategy (What you will do in your course) | Alignment and/or challenges mitigated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Example:

Useful |

Example:

Foster generative processing |

Example:

I will build in ungraded self-assessment quizzes at the end of each module |

Example:

This is aligned with Course goals

Assessments

This helps mitigate the previous issues of

|

| Desirable | |||

| Useful | |||

| Credible | |||

| Intuitive | |||

| Accessible |

References and credits

Troop, M., White, D., Wilson, K. E., & Zeni, P. (2020). The User Experience Design for Learning (UXDL) Framework: The undergraduate student perspective. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2020.3.8328

University of Waterloo, UXDL Honeycomb

The sections “Course Content Design for Humans” and “Identifying Learner–Content Interactions” is derived from the original Fostering Engagement: Facilitating Online Courses in Higher Education, Unit4a by K.E. Wilson and D. Opperwall, which is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. The derivative work, “Course Content Design for Humans” and “Identifying Learner–Content Interactions” has been adapted through modification of text, images, and headings and retains the CC BY-NC-SA International 4.0 license.