Module 1: Designing for connection

1.3 Setting the stage for significant and courageous learning

Key principles: Human learning

Human learning, in the human brain, is a social process, that is relational by nature and marked by attention to and observation of other humans and their behaviour. The processes involved in learning how to walk and speak is not fundamentally different from learning how to build a website or formulate a well-supported academic argument. We learn through observation, and practice when we have the courage to engage, put in effort, make mistakes, fail, and then try again. Teaching is achieved not just by telling, but by showing, modeling, and providing specific and timely encouragement and constructive feedback.

Asking learners to be open, to put in effort, and to change as a result of the learning they will do in your course is difficult work requiring a degree of vulnerability, and therefore courage. We’ll look more closely at this in the next section in this module, where you’ll also find resources from Brené Brown and her model for creating daring classrooms. Significant and transformational learning is grounded in trust and transformational teaching is an act of caring.

Reflect and apply: Reflection on transformational learning and courageous learning strategies

How to complete this activity and save your work:

Type your response to the questions in the box below. Your answers will be saved as you move forward to the next question (note: your answers will not be saved if you navigate away from this page). Your responses are private and cannot be seen by anyone else.

When you complete the below activity and wish to download your responses or if you prefer to work in a Word document offline, please follow the steps below:

- Navigate through all tabs or jump ahead by selecting the “Export” tab in the left-hand navigation.

- Hit the “Export document” button.

- Hit the “Export” button in the top right navigation.

To delete your answers simply refresh the page or move to the next page in this course.

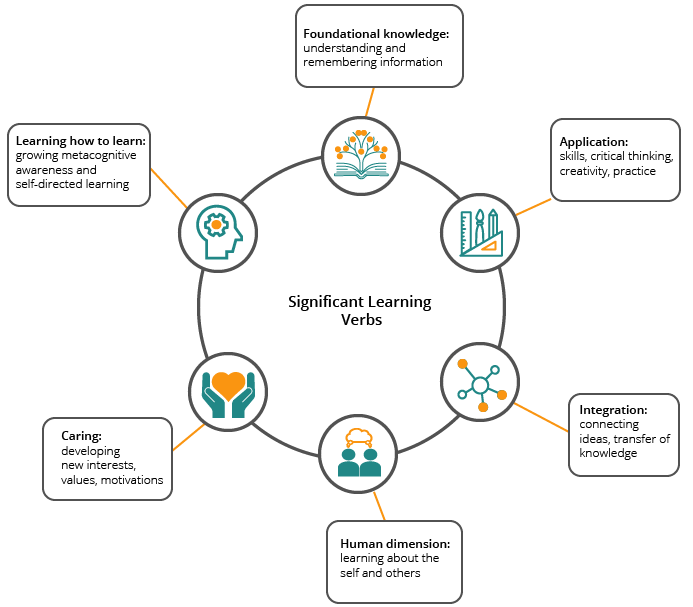

Taxonomy of significant learning

One helpful framework for designing significant and transformational learning experiences is Fink’s taxonomy of significant learning (Fink, 2003). This taxonomy is rooted in the notion that learning involves a change or transformation in the learner. There are six key dimensions in the Taxonomy of Significant Learning that we can use to guide the design (setting course goals, learning outcomes, design of content and assessments of learning) of virtual courses.

Foundational knowledge

This dimension is essentially what many instructors think of first when describing their course or explaining what they teach. This includes the content, concepts, and information that you want your learners to grasp and involves operationalizing how you will assess foundational knowledge. As an area of learning assessment, foundational knowledge, is most commonly the focus of assessments, especially in introductory courses, but there are often other important goals instructors have for even their most novice students.

Application

This dimension is about taking earlier learning or knowledge and applying it in a new context or through hands-on engagement and experimentation. This can include critical appraisal and evaluation, reflection, and expansive, creative, and/or practical thinking and problem-solving.

Integration

This dimension is all about making connections and the transfer of learning to new contexts. This can include connecting concepts across the course, different courses within a program or discipline, different disciplines, or to other aspects of one’s life, profession, and society.

Human dimension

This dimension reflects learning about the self and others and relates to the kind of sense making, significance, and relevance realization that helps learners deeply connect and be transformed by learning. This dimension is grounded in the self and the social connections learners are able to make and grow.

Caring

This dimension reflects a shift in what learners care about and involves the development of learners’ interests, motivations, values, and feelings and can translate into significant effort and the courage to do hard things.

Learning to learn

This dimension is about the process of learning to learn, developing the kind of metacognition and insight into one’s own learning, and/or the discipline of study that enables learners to move towards more self-directed learning. This is the foundation for life-long learning.

Key principles: SMART learning outcomes for transformational learning

When designing or redesigning a virtual course it is helpful to start by identifying your goals for learning in your course—i.e., which dimensions of significant learning you expect your course to foster and your learners to achieve. Then identify how you will assess whether your learners have met these goals. You can then write the course-level learning outcomes (LOs), which describe to students in clear and explicit terms what you expect them to learn and how they will be expected to demonstrate their learning.

Useful LOs take the guess work and interpretation that students need to do around vague words like “understand” and “know” by telling them how you and your discipline measure understanding and knowing. LOs are best phrased as actions (using verbs) and are SMART:

- Specific: clearly state what is to be done (action) that will be assessed

- Measurable: indicate how the outcome will be measured

- Achievable: realistic given the topic of the course, the stage or learning the learner is at, and time and resource constraints

- Relevant: aligns with the goals of the course/module

- Time-bound: clear and reasonable bounds on the time expected for the outcome to be demonstrated

The importance of LOs for course authors, instructors, & learners

Taking some time before you design and develop your course to think through and articulate your LOs can help you make important and time-saving decisions about what content to include, how to present that content, and designing assessments that really measure the learning that matters. The importance of making this plan is analogous to planning a road trip:

- the significant learning goals (your learners’ destination)

- a plan for how you will help learners achieve those goals (the route to get to the destination)

- a way of checking that they achieved the goals (ways of assessing that they arrived at the intended destination)

A course without a clear destination, route, and/or a way of knowing whether one has arrived can make course design decisions particularly difficult and inefficient. Knowing where you want learners to end up and how you will know they got there will help you to work efficiently in

- selecting the topics you will teach (what is essential vs. what is enrichment or supplementary),

- how you will teach them (what methods will transmit the content and enable them to transform that into significant learning), and

- the assessments you need to evaluate whether learners met these goals of significant learning.

Sharing these LOs with students is essentially like giving them the road map to the course and ensures that all of this is transparent. Helping learners understand what is important to you and the goals of the course helps them to manage their time, focus on what is important and relevant, self-assess their own learning, and prepare for assessment.

Creating SMART LOs using significant learning verbs

Let’s take a closer look at each of the dimensions of significant learning and learning outcome verbs commonly associated with each.

Table. Fink’s six dimensions of significant learning and measurable learning outcomes.

| DIMENSION OF SIGNIFICANT LEARNING | LEARNING OUTCOMES |

|---|---|

| FOUNDATIONAL KNOWLEDGE |

|

| APPLICATION |

|

| INTEGRATION |

|

| HUMAN DIMENSION |

|

| CARING |

|

| LEARNING TO LEARN |

|

Going deeper

To learn more about Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant learning:

- Fink, L. D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences. Jossey Bass.

The following resource provides an account of how a developmental psychologist applied Fink’s Taxonomy and redesigned her courses (as did 5 of her colleagues) and the results of her pre-post study that showed significant improvement in learning:

For more information on developing significant learning outcomes and a list of more useful verbs see the following resources:

For more information on taking a nonhierarchical and EDDI approach to developing SMART LOs, visit the following interactive tool. You’ll be able to see examples there and export your initial ideas for creating new learning outcomes using this holistic framework:

For further learning on how to appropriately consider this framework, refer to Module 2.6 The Road to Decolonizing and Indigenizing a Virtual Course.

Key principles: Three types of connection for significant learning

In translating Fink’s dimensions of significant learning to the virtual context, it is important to think about how learners will interact with you, the content and skills training, and their peers, as these three basic forms of connection are critical to humanizing learning. Think about it this way:

- Fink’s taxonomy is helpful for identifying the key goals/learning outcomes that matter to you, your discipline and/or program and

- the three types of connection/interaction are how (what we do) to achieve those goals in a virtual course.

Michael G. Moore (1989) highlighted these three essential types of connection or interactions that are important for learners to succeed in a given course, especially one taken at a distance.

The three basic forms of connection are

Moore’s interactions are the discreet spheres or spaces in which opportunities for authentic engagement and significant learning can be found. We can think of these three forms of interaction as the touchpoints, points of connection, transmission, and interaction through which significant virtual learning occurs. We will elaborate on these modes of connection (both in the design and delivery of virtual courses), providing strategies and examples of the many ways you can create opportunities for these connection points in virtual courses and how they can be used to foster significant learning across the six dimensions.

Strategies in action: Alignment tables

Alignment tables are useful for creating a map to your virtual course and will set the direction of your approach to course design and delivery, including

- your course goals (prioritized dimensions of significant learning),

- learning outcomes,

- assessments, and

- identifying the modes of interaction and connection that will enable the transfer of knowledge and learning (learner–instructor, learner–learner, learner–content).

The following are example alignment tables from a range of courses:

- English Literature course (Waterloo)

- Intro to Stats course (Waterloo)

- Psychology – Basic Processes of Behaviour (Conestoga)

- Capstone II – Organizational Consulting Project (Conestoga)

Reflect and apply: Aligning learning outcomes, assessments, and connection

(Re)create alignment tables for your own course by

- reflecting on the significant learning goals that are most important to you and/or required by the department/program (maybe make a prioritized list);

- brainstorming how you might assess whether your learners are meeting these goals;

- writing learning outcomes that use verbs that describe how each dimension/goal will be assessed or how learners will be asked to demonstrate the achievement of that goal; and

- identifying whether your assessments rely on or involve all three forms of connection/interaction (learner–instructor, learner–learner, learner–content). Assessments most commonly focus on learner-content interaction. Can you find opportunities to build all three forms of connection into this course plan that will help enrich the significant learning you have planned through interactions with you, TAs, and their peers?

Note: Throughout this course we encourage you to come back to this table and adjust and modify if you come across a new strategy that helps you create opportunities for all three forms of connection and/or richer connections.

Remember that you can work in this page or offline in a Word document by going to the last item on this list “Export” to download the questions and your answers. Alternatively, if you prefer to work in a table format, we have included downloadable templated alignment tables at the bottom of this interaction.

How to complete this activity and save your work:

Complete the alignment chart by typing your details in the boxes below. Your answers will be saved as you move forward to the next question (note: your answers will not be saved if you navigate away from this page). Your responses are private and cannot be seen by anyone else.

When you complete the below activity and wish to download your responses or if you prefer to work in a Word document offline, please follow the steps below:

- Navigate through all tabs or jump ahead by selecting the “Export” tab in the left-hand navigation.

- Hit the “Export document” button.

- Hit the “Export” button in the top right navigation.

To delete your answers simply refresh the page or move to the next page in this course.

Templated alignment tables

Course-Level (DOCX)

Module-Level (DOCX)

References and credits

Fink, L. D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences. Jossey Bass.

Moore, M. G. (1989). Three types of interaction. The American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1–6.