Module 3: Course Design and Implementation

Turning Program Vision into Curriculum

Lauren Anstey

Imagine building a house with no blueprint. The contractors have all the right skills and tools to construct the foundation and the walls of the home, but they need to know the overall configuration and design of the home to build something that’s not only structurally sound but is ultimately functional and aesthetically pleasing for the people who will live in it day-to-day.

The blueprint is designed to reflect the builder’s or homeowner’s desired functionality, design, and architectural intentions. For example, the roof of a barn has been intentionally designed as gambrel shaped, or a Tudor archway is planned as the entryway of a home taking inspiration from the Medieval architecture in England and Wales. There is intentionality behind the blueprint that reflects early decision-making and overall design.

This is an analogy for course design. A course design team may have the requisite skills for designing and building courses for the program, and yet they need the ‘blueprint’ to guide the overall structure of the course explicitly and purposefully. The ‘blueprint’ in this case is a curriculum design plan that may inform how learning will be facilitated, the sequence of course events, how learners will be assessed, how aspects of a course relate to one another, and how the course relates to other courses in the program. Just as a developer plans a whole neighbourhood by designing and building multiple houses that are each unique yet similar in their common architectural design, an academic program can plan for a cohesive whole – a common architectural design that intersects each course in the program while also allowing each course design to be unique to the needs of the learning outcomes, instructor, and students.

Your program has already begun to build the ‘blueprint’ by articulating the program’s vision. In Module 2: Why Have a Program Vision? a program vision was defined as the high-level goal or “why” statement that forms the foundation of any program framework. The vision is central to understanding the program and its needs and is something to return to regularly to ensure the desired purpose and values for the program remain in focus. A program’s vision is directly influential upon the program’s curriculum. However, there’s an important distinction to make here. While the program’s vision is the high-level intention and foundation to the program’s framework, the curriculum is the enacted qualities of teaching and learning within and across courses. If the vision is the “why?” of the program, the curriculum is the “how?” and “through what pedagogical means?” will learners engage in achieving that “why?”

After articulating a program vision and set of program learning outcomes, “the next task was to consider how to translate these lofty goals and desired outcomes into a set of educational experiences that would provide students with the necessary skills and knowledge to succeed in achieving those outcomes,” say program developers Backenroth and Sinclair (2014, p. 130). Structural and curricular decisions had to be made as “guided by our existential vision” (p. 130).

While your vision may be lofty, existential, and high-level, your robust curriculum plan will be enacted, nuanced, and fine-detailed. This unit will help you take the program vision and advance it into an aligned and cohesive curriculum plan that will serve to guide course-by-course design and development.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this unit, you will be able to:

- Translate overall program vision, outcomes, and students’ needs into a curriculum plan shaping course development

- Select models of curriculum design for framing a cohesive and habitual approach to course development

You will take away:

- Strategies and ideas for creating a curriculum design plan with their team

This unit focuses on the Program Vision, Course Design, and Teaching and Learning elements of the Online Program Ecosystem. Read more about the ecosystem in Module 1, Unit 1: Collaborating to Create the Online Learner Life Cycle and its Ecosystem

Designing a new course or a series of new courses is a rare opportunity to create conditions for success from the start. The success of your online program will be measured by your ability to enact the program’s vision and foster students’ learning toward achieving intended outcomes. This learning ultimately happens at the course level. Make key course design decisions now, at the start of the design process. This will not only result in a well-designed program that consists of cohesive, innovative courses, but it will also save time as courses get designed and developed in connection to the overall program vision rather than needing to be reworked or redesigned later on, once misalignments have been flagged.

Core Components, Philosophies, Pedagogies, or Forms of Engagement Shaping Curriculum

You might be wondering what shapes curriculum design (hint: it’s not the content). This section intends to present various sources of inspiration that will help address this question. We might ask:

What core components, philosophies, pedagogies, or forms of engagement would you expect to see if observing the teaching and learning happening within the courses that comprise your program?

It is by no means the intention of this module to outline and present all the possible components, philosophies, pedagogies, and forms of engagement that could be drawn upon in shaping that ‘blueprint’ for course design. It’s impossible! In fact, some of the best ‘blueprints’ are shaped by pulling on disciplinary perspectives or disparate and creative ideas that arise out of deeply contextualized conversations between visionaries of the program. It is the intention of this section to offer a few starting points and critical questions for guiding that conversation so that creative and transformative possibilities can arise as a new signature quality of your program. You’ll also notice this unit is not focused on clarifying course content. This is not about the key concepts and material that will be covered in courses. This is about how students will learn and instructors will teach rather than what instructors will teach or students will learn.

Pre-Check: Assess your Readiness for Exploring Models

Before entering into a process of course planning based on alignment to program outcomes, there are a few things you can consider in assessing readiness. Answer the questions below to assess your readiness to engage in an exploration of course design models.

What core components, philosophies, pedagogies, or forms of engagement would you expect to see if observing the teaching and learning happening in the courses that make up your program?

You can keep track of your written reflections in the Program Design and Implementation Workbook.

Various Perspectives on Core Components, Philosophies, Pedagogies, and Approaches

This section offers an initial overview of the various perspectives that may resonate with program leaders as they explore the main question of this unit further: What core components, philosophies, pedagogies, or forms of engagement would you expect to see if observing the teaching and learning happening within the courses that comprise your program?

You can keep track of your written reflections in the Program Design and Implementation Workbook in the Unit Reflection section for this module.

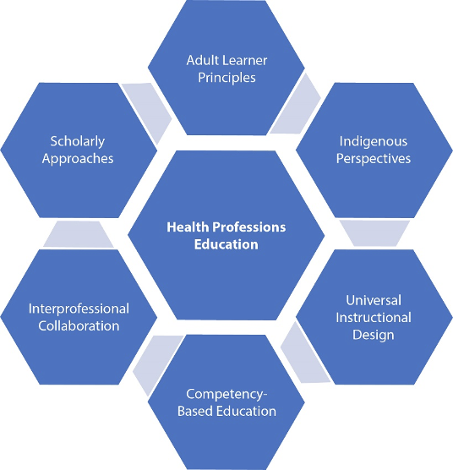

Core Components

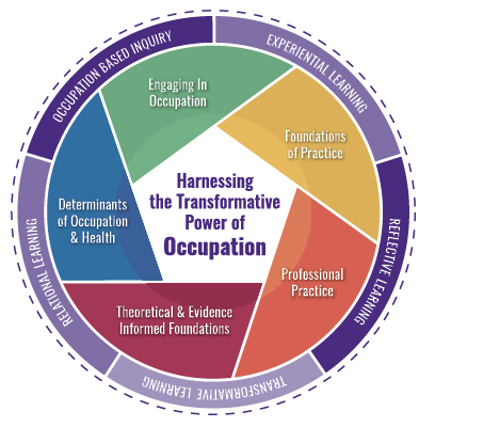

Core components or key characteristics of a program are the essential factors, traits, and qualities that consistently shape the program’s curriculum. Consider these three examples (keep in mind – these examples and the visual representation of core components reflected in each are the polished versions after much deliberation and iteration!):

Denise Stockley (Co-Director of the Master’s in Health Professions Education, Queen’s University) is interviewed to explain what Example 1 represents, how she and colleagues first came up with the model, and how the model continues to be utilized in the program.

Philosophy of Teaching

Borrowing from the concept of a Teaching Philosophy, this section is focused on developing and articulating a Program Teaching Philosophy as a frame of reference for informing curriculum and course design. Schönwetter et al. (2002) defined a teaching philosophy statement as “a systematic and critical rationale that focuses on the important components defining effective teaching and learning in a particular discipline and/or institutional context” (p. 84). Commonly expressed by individual instructors in articulating their teaching philosophy that informs their teaching practice, here we extend the concept of a teaching philosophy to the program. Though it may become expressed as a statement (possibly even as part of your program vision statement), what’s important here is to consider the distinctive aims, values, beliefs, and convictions that provide an organizing vision of the [program’s] direction and a rationale towards which [program] efforts are geared” (p. 84).

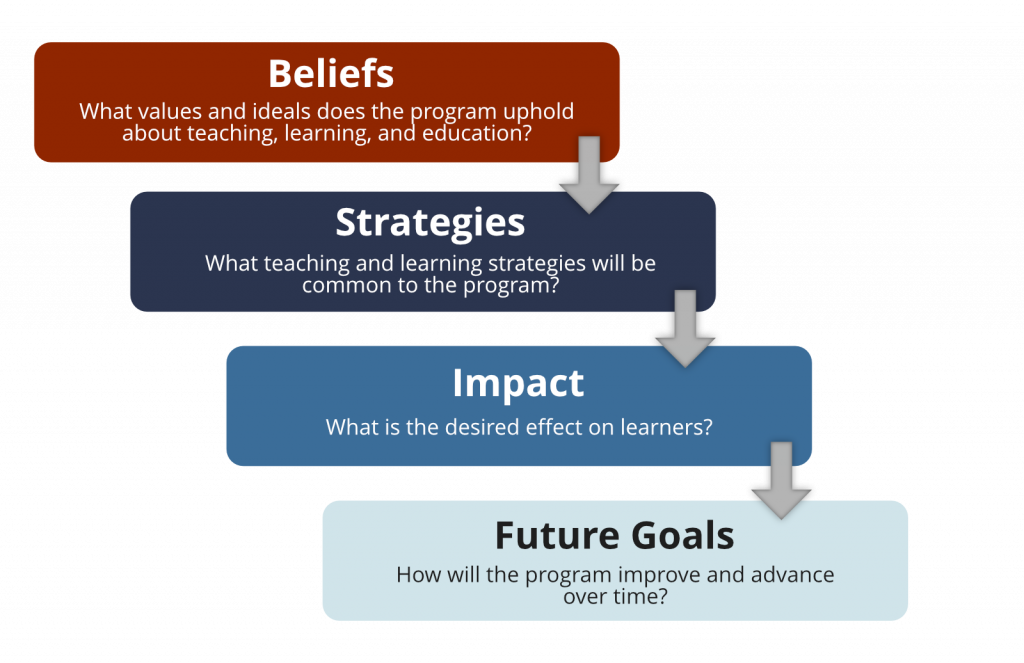

As a personal philosophy statement, a program’s philosophy identifies:

- Beliefs (what values and ideals the program upholds about teaching, learning, and education?)

- Strategies (what teaching and learning strategies will be common to the program?)

- Impact (what is the desired effect on learners?)

- Future Goals (How will the program improve and advance over time?)

The following questions have been adapted from the literature (Schönwetter et al., 2002; Kenny et al., 2018) that typically guides individual instructors on articulating and writing their statement to apply at a program level. While at first you may reflect on these questions independently as you read, these questions are intended as conversation starters for members of the program design team, such that a program philosophy is developed collaboratively. For this reason, you can download the Program Philosophy Slide Deck as a resource for facilitating conversation with your group.

Collaborative approaches invite us to consider whose beliefs, values, and goals are shaping this process, and who’s missing, undervalued or underrepresented. Before leading this conversation, consider how equity-deserving persons and under-represented perspectives can be included, centred, and prioritized so that the program’s philosophy is inclusive, diverse, and equity-driven.

Beliefs

- What are our beliefs about teaching and learning in this program?

- What assumptions are we making about the essential skills, knowledge, and values we aim to teach through this program?

- Why do we hold these beliefs?

- What attributes and values do we wish to impart to students?

- What code of ethics guides teaching in the program?

Strategies

- What does good teaching look like in this program?

- What kinds of student-teacher relationships do we strive for in this program?

- What themes pervade teaching in the program?

- Under what opportunities and parameters will enable students to learn effectively in this program?

Impact

- How will we measure successful teaching in the program? What does successful teaching look like?

- What habits, attitudes, methods will mark successful teaching in the program?

- What are we trying to achieve with our students?

Future Goals

- What are our future goals and aspirations for the program?

- Where will we be in 7 years?

Signature Pedagogies

Signature Pedagogies are “the types of teaching that organize the fundamental ways in which future practitioners are educated for their new professions” (Schulman, 2005). They are the pervasive and routine ways of teaching and learning that cut through all topics and courses and typically entail public student performance. In other words, what kinds of performances might students need to engage in and demonstrate to express their growth into becoming future practitioners of the discipline?

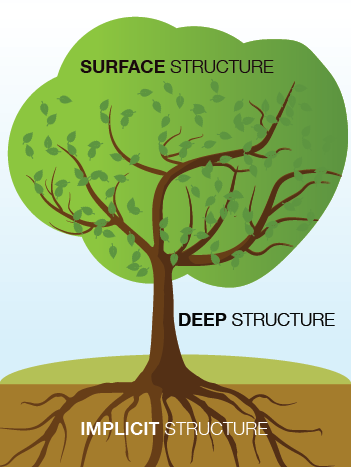

There are three dimensions to a signature pedagogy:

- Surface Structure: Concrete, operational acts of showing and demonstrating, of questioning and answering, of interacting and withholding.

- Deep Structure: A set of assumptions about how best to impart a certain body of knowledge and know-how

- Implicit Structure: A moral dimension that comprises a set of beliefs about professional attitudes, values, and dispositions.

The following questions are based on Shulman’s concept of Signature Pedagogies. While at first you may reflect on these questions independently as you read, these questions are intended as conversation starters for members of the program design team, such that the team might identify those pervasive pedagogies of your program that will “cut through all topics and courses.” For this reason, you can download the Signature Pedagogies Slide Deck as a resource for facilitating conversation with your group.

Thinking of the teaching and learning practices perceived, imagined, or planned for the program, reflect on these types of questions that target each of the three dimensions –

Surface Structure:

- What are or what should be concrete, operational acts of showing and demonstrating learning within this field of study?

Deep Structure:

- What assumptions are we making about how best to impart knowledge and know-how within this program?

Implicit Structure:

- What professional attitudes, values, and dispositions comprise this program?

- What teaching and learning practices would you be proud to see included in the courses comprising this program?

- What is unique or special about what you do when you’re teaching in the areas/topics that will become a part of this program?

- What pedagogical practices will enable students to think, perform, or act with integrity for the profession/engagement in the field? Why is this a valuable pedagogy for the program?

Forms of Engagement

Various models of education – particularly those representing conceptions of student engagement and/or online student engagement more specifically – can inspire conversations regarding program curriculum and course design. Below, two such models are introduced: (1) Community of Inquiry, and a (2) Holistic Framework for Student Success.

Community of Inquiry

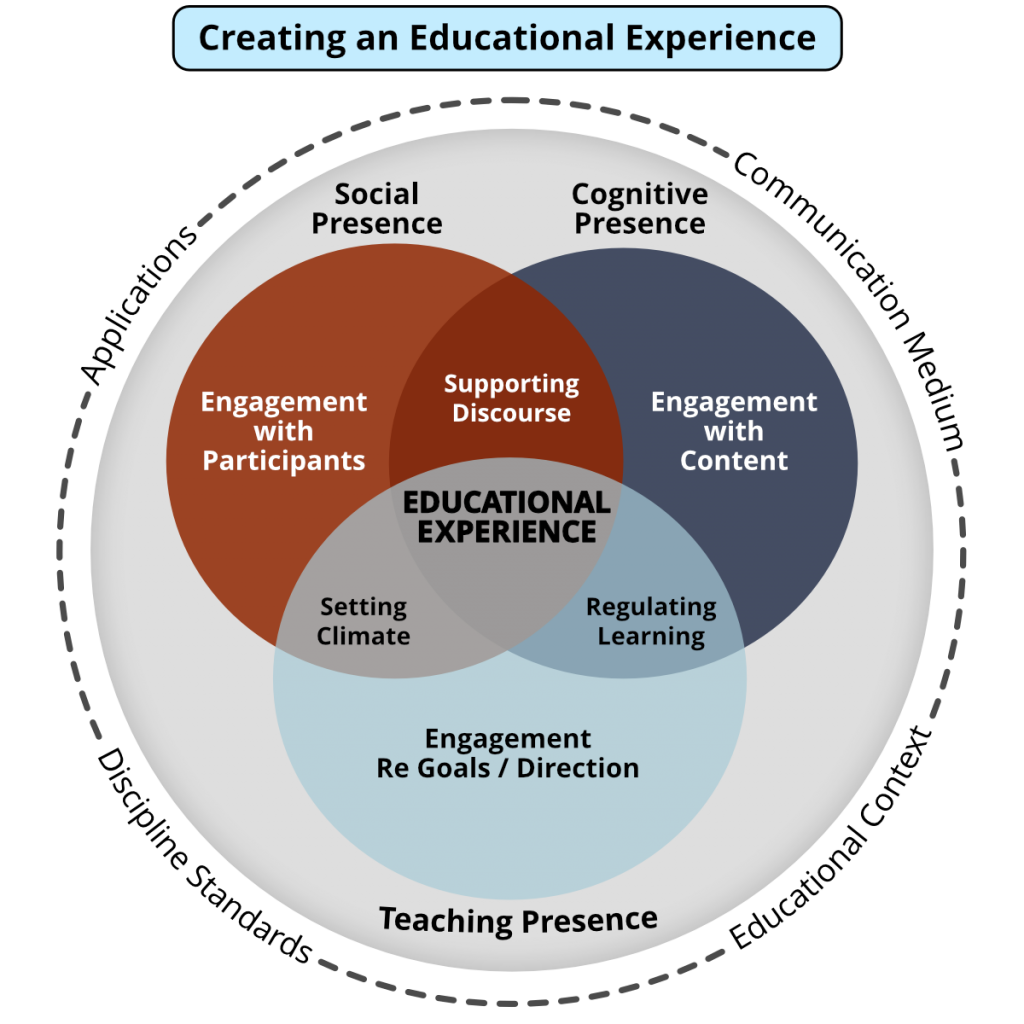

The Community of Inquiry (CoI) model was specifically developed to capture online teaching as a “complex process that requires rethinking the role of the instructor, student interactions, and meaningful ways of learning” (Garrison et al., n.d.). “The CoI framework gets at the heart of establishing and sustaining online educational experiences” (Perova-Mello & Pitterson, 2020) through a process of “creating a deep and meaningful (collaborative-constructivist) learning experience through the development of three interdependent elements – social, cognitive, and teaching presence” (Garrison et al., n.d.). For many online educators, the CoI framework has played a critical role in thoughtful design of online education, by offering “practical ways of helping students learn through active participation and shared meaning making” (Perova-Mello & Pitterson, 2020).

In the CoI model, teaching presence is the design, facilitation, and direct instruction. It is the thoughtful ways in which instructors design and organize their teaching and the course curriculum, how they facilitate discourse by setting the learning environment within a course, and how they engage in direct instruction (for example, how they present information or summarize discussion), while “social presence is described as the ability to project one’s self and establish personal and purposeful relationships” (Garrison, 2007, p. 63). This presence recognizes the social aspects of learning where group cohesion is shaped by effective and open communication between learners. Cognitive presence is, “the exploration, construction, resolution and confirmation of understanding through collaboration and reflection” (Garrison, 2007, p. 65). Drawing heavily on concepts of inquiry and experiential learning (such as the foundational works of Dewey and Kolb), cognitive presence is informed by a cycle of practical inquiry where “participants move deliberately from understanding the problem or issue through to exploration, integration and application” (p. 65).

Conceptualize your program as a Community of Inquiry.

How do teaching, social, and cognitive presence get reflected in your program? The following questions are organized based on each of the CoI presence areas. While at first you may reflect on these questions independently as you read, these questions are intended as conversation starters for members of the program design team, such that the team might identify draw on elements of cognitive, social, and teaching presence to articulate the defining nature of the program and course curriculum. For this reason, you can download the Community of Inquiry Slide Deck as a resource for facilitating conversation with your group.

Teaching Presence

- What course design elements and eLearning tools could be commonly used to support teaching presence through design, facilitation, and direct instruction?

- How and when throughout the program will instructors directly facilitate and instruct students? What does this look like for the program?

- Thinking about how instructors might set a particular course climate, are there commonalities between courses that students would expect to experience in each course they take?

- Generally, how might instructors facilitate discourse within the program? What characteristics do instructors teaching in the program share? When do the unique qualities/characteristics of individual instructors strongly align with the overall intentions of the program?

- How will learners receive feedback from their instructors throughout the program?

Social Presence

- What course design elements, including eLearning tools, could be commonly used to support social presence, (emotional affective) expressions, open communication, and group cohesion?

- How will students be supported to develop trust and interact among peers?

- What etiquette or moral guidelines characterize what open and effective communication among learners looks like for the program?

- When and how will students work together?

Cognitive Presence

- What course design elements could be commonly used to support students’ exploration, construction, resolution and confirmation of understanding through collaboration and reflection?

- How will students be supported to move deliberately from understanding the problem or issue through to exploration, integration, and application both within courses and across courses?

- When and how will learners be first introduced to concepts and how will they be encouraged to explore those concepts?

- When and how will learners engage in analysis and synthesis?

- When and how will learners pause to reflect on learning?

Holistic Framework for Student Success

The second model presented here is the Holistic Framework for Student Success designed by Yunyi Chen (Centre for Teaching and Learning, Queen’s University). The tool below walks curriculum designers through a process for designing curriculum around Fink’s (2003) Taxonomy of Significant Learning, as oriented and integrated with Indigenous Ways of Knowing.

Curriculum Design Models

Exploring the various core components, philosophies, pedagogies, or forms of engagement that will shape your curriculum has hopefully offered new ways of articulating the design principles that will guide curriculum development, carrying the thread of program vision into the curricular considerations of teaching and learning. Next, your goal is to advance this principled start into a scaffold for curriculum design. For that, we need to purposely consider curricular structures in terms of sequence and degree of interconnectedness between significant components of learning. In other words: What learning will happen when and in what order? To what degree will pieces of the curriculum intersect, relate, or connect to one another?

Click through the interactive object below to learn more about four ways of structuring and designing curriculum.

Unit Reflection and Resources

Overall, this unit has presented a wide range of models, approaches, and frameworks for conceptualizing a program’s curriculum. These ideas are intended to inspire and inform your approaches to building a cohesive and habitual approach to course development that reflects the program’s vision and essential qualities of learning. With a shared understanding of the core components, philosophies, pedagogies, or forms of engagement that enact the program’s vision into the curriculum, you’ll be in a position to work these values into the fabric of students’ learning experiences.

Reflecting on this unit, consider:

- What resonates?

- Which elements of this unit resonate with you and other leaders of the program?

- How do you plan to adopt or adapt the pieces that resonate with your program curriculum design work?

Actionable Tasks

What’s next? On reflection of what resonates, consider as well what your next steps will be with this information. How will you proceed in working with these ideas as you progress with program developments?

How can this be used to drive conversation? One of the most critical elements of curriculum design is ongoing conversation with key stakeholders such as program leaders, identified instructors, course developers, future students, and other stakeholders as identified.