13 Understanding Death

Anne Baird

One way to understand death and dying is to look more closely at what defines physical death and social death.

Death Defined: According to the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) (Uniform Law Commissioners, 1980), death is defined clinically as the following:

- An individual who has sustained either (1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, or (2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem, is dead. A determination of death must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.

The UDDA was approved for the United States in 1980 by a committee of national commissioners, the American Medical Association, the American Bar Association, and the President’s Commission on Medical Ethics. This act has since been adopted by most states and provides a comprehensive and medically factual basis for determining death in all situations.

Death Process: For those individuals who are terminal and death is expected, a series of physical changes occur. Bell (2010) identifies some of the major changes that occur in the weeks, days, and hours leading up to death (pp. 5, 176-177):

| Weeks Before Passing | Days Before Passing | Days to Hours Before Passing |

|

|

|

Social death begins much earlier than physical death (Pattison, 1977). Social death occurs when others begin to dehumanize and withdraw from someone who is terminally ill or has been diagnosed with a terminal illness (Glaser & Strauss, 1966). Dehumanization includes ignoring them, talking about them if they were not present, making decisions without consulting them first, and forcing unwanted procedures.Sweeting and Gilhooly (1997) further identified older people in general, and people with a loss of personhood, as having the characteristics necessary to be treated as socially dead. More recently, the concept has been used to describe the exclusion of people with HIV/AIDS, younger people living with terminal illness, and the preference to die at home (Brannelly, 2011). Those diagnosed with conditions such as AIDS or cancer may find that friends, family members, and even health care professionals begin to say less and visit less frequently. Meaningful discussions may be replaced with comments about the weather or other topics of light conversation. Doctors may spend less time with patients after their prognosis becomes poor.

Why do others begin to withdraw? Friends and family members may feel that they do not know what to say or that they can offer no solutions to relieve suffering. They withdraw to protect themselves against feeling inadequate or from having to face the reality of death. Health professionals, trained to heal, may also feel inadequate and uncomfortable facing decline and death. People in nursing homes may live as socially dead for years with no one visiting or calling. Social support is important for quality of life, and those who experience social death are deprived from the benefits that come from loving interaction with others (Bell, 2010).

Why would younger or healthier people dehumanize those who are incapacitated, older, or unwell? One explanation is that dehumanization is the result of the healthier person placing a protective distance between themselves and the incapacitated, older, or unwell person (Brannelly, 2011). This keeps the well person from thinking of themselves as becoming ill or in need of assistance. Another explanation is the repeated experience of loss that paid caregivers experience when working with terminally ill and older people requires a distance which protects against continual grief and sadness, and possibly even burnout.

Most Common Causes of Death

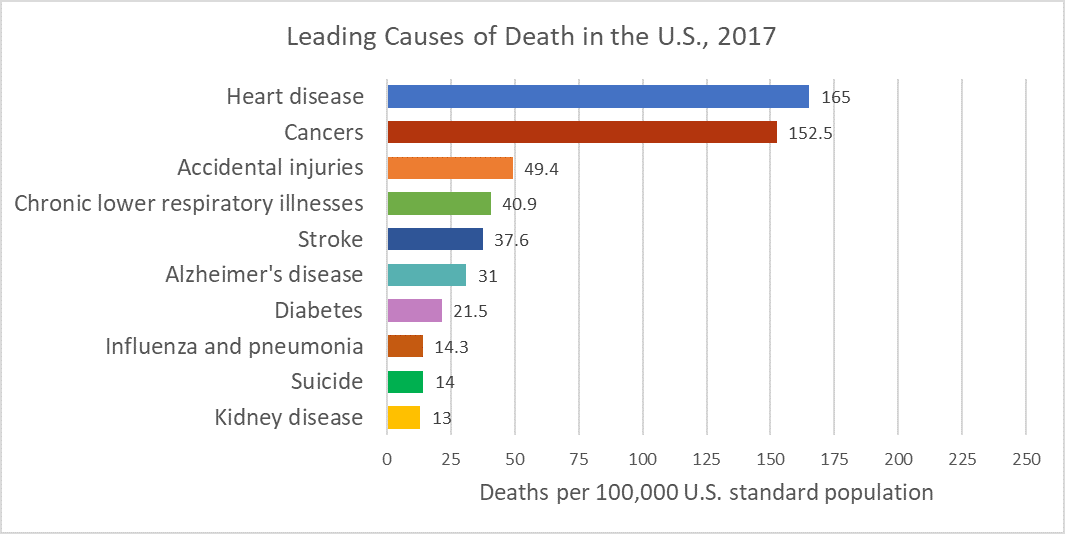

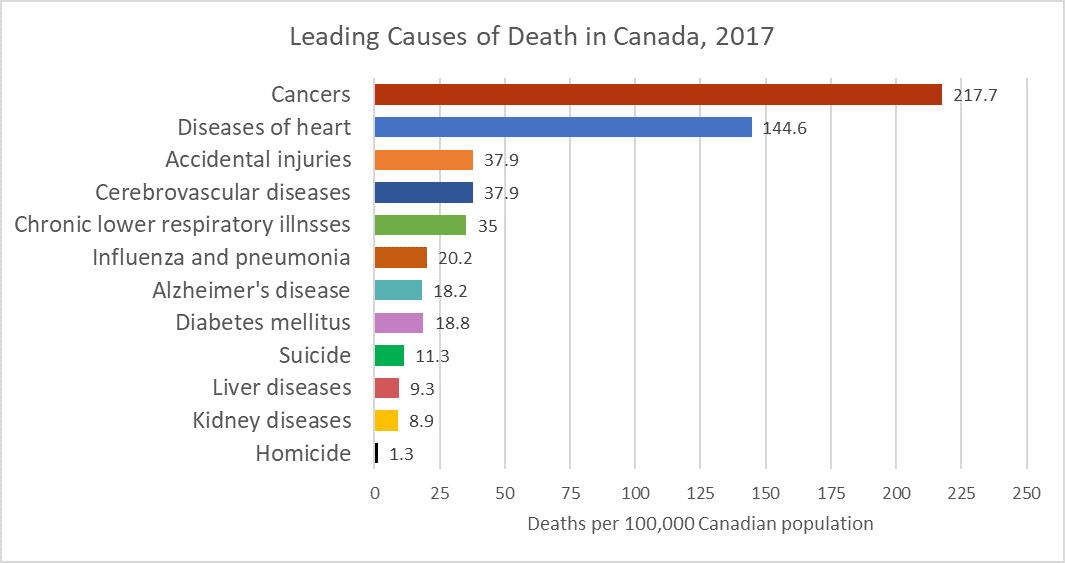

In 1900, the most common causes of death were infectious diseases, which brought death quickly. Today, the most common causes of death are chronic diseases in which a slow and steady decline in health ultimately results in death. In 2017, heart disease, cancer, and accidental injuries were the leading causes of death (image 3.12.2 adapted from CDC, 2017). Canada has similar leading causes with slight differences in the overall numbers and order (image 3.12.3 adapted from Statistics Canada, 2017).

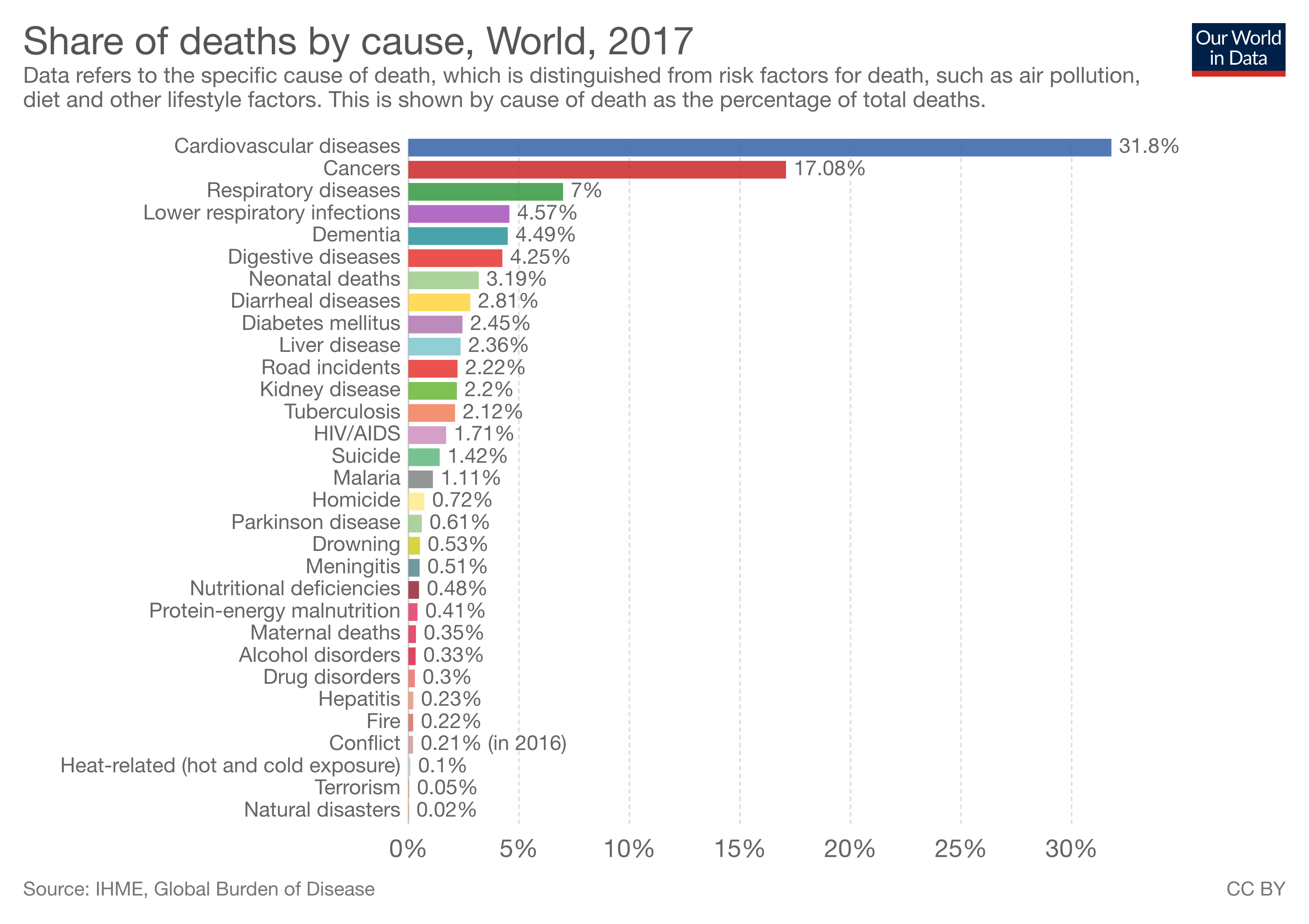

The World: The most recent statistics analyzed by the World Health Organization were in 2012, and non- communicable deaths; that is, those not passed from person- to-person, were responsible for 68% of deaths (WHO, 2016). The four most common noncommunicable diseases were cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and chronic lung diseases. In contrast, communicable diseases, such as HIV and other infectious diseases, neonatal and maternal mortality, and nutritional problems caused 23% of the deaths combined, and injuries caused the remaining 9% of the deaths. Image 3.12.4 depicts slightly more recent data from 2017 (Our World in Data).

The causes of death vary by age. In infancy, congenital problems and other birth complications are the largest contributors to infant mortality. Accidents, known as unintentional injury, become the leading cause of death throughout childhood and early adulthood. In middle and late adulthood cancer and heart disease become the leading killers.

Tobacco use is attributed as one of the top killers, and is often the hidden cause behind many of the diseases that result in death, such as heart disease and chronic lung diseases (WHO, 2016).

These statistics hide the differences in the causes of death among high versus low income nations. In high-income countries, defined as having a per capita annual income of $12,476 or more, 70% of deaths are among people aged 70 and older. Only 1% of deaths occur in children under 15 years of age. People predominantly die of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, cancers, dementia, or diabetes. Lower respiratory infections remain the only leading infectious cause of death in such nations. In contrast, in low-income countries, defined as having a per capital annual income of $1025 or less, almost 40% of deaths are among children under age 15, and only 20% of deaths are among people aged 70 years and older. People predominantly die of infectious diseases such as lower respiratory infections, HIV/AIDS, diarrheal diseases, malaria and tuberculosis. These account for almost one third of all deaths in these countries. Complications of childbirth due to prematurity, birth asphyxia, and birth trauma are among the leading causes of death for newborns and infants in the poorest of nations (WHO, 2016).

WHERE DO PEOPLE DIE?

Gathering statistics on the location of death is not a simple matter. Those with terminal illnesses may be going through the process of dying at home or in a nursing home, only to be transported to a hospital in the final hours of their life. Thus, it should not be a surprise that in the United States, more Americans die in hospitals than in any other settings. Internationally, 54% of deaths in over 45 nations occurred in hospitals, with the most frequent occurring in Japan (78%) and the least frequent occurring in China (20%), according to a study by Broad et al. (2013). They also found that for older adults, 18% of deaths occurred in some form of residential care, such as nursing homes, and that for each decade after age 65, the rate of dying in a such settings increased 10%. In addition, the number of women dying in residential care was considerably higher than for males.

Development Perceptions of Death and Death Anxiety

The concept of death changes as we develop from early childhood to late adulthood. Cognitive development, societal beliefs, familial responsibilities, and personal experiences all shape an individual’s view of death (Batts, 2004; Erber & Szuchman, 2015; National Cancer Institute, 2013).

Infancy: Certainly infants do not comprehend death, however, they do react to the separation caused by death. Infants separated from their mothers may become sluggish and quiet, no longer smile or coo, sleep less, and develop physical symptoms such as weight loss.

Early Childhood: As you recall from Piaget’s preoperational stage of cognitive development, young children experience difficulty distinguishing reality from fantasy. It is therefore not surprising that young children lack an understanding of death. They do not see death as permanent, assume it is temporary or reversible, think the person is sleeping, and believe they can wish the person back to life. Additionally, they feel they may have caused the death through their actions, such as misbehavior, words, and feelings.

Middle Childhood: Although children in middle childhood begin to understand the finality of death, up until the age of 9 they may still participate in magical thinking and believe that through their thoughts they can bring someone back to life. They also may think that they could have prevented the death in some way, and consequently feel guilty and responsible for the death.

Late Childhood: At this stage, children understand the finality of death and know that everyone will die, including themselves. However, they may also think people die because of some wrong doing on the part of the deceased. They may develop fears of their parents dying and continue to feel guilty if a loved one dies.

Adolescence: Adolescents understand death as well as adults. With formal operational thinking, adolescents can now think abstractly about death, philosophize about it, and ponder their own lack of existence. Some adolescents become fascinated with death and reflect on their own funeral by fantasizing on how others will feel and react. Despite a preoccupation with thoughts of death, the personal fable of adolescence causes them to feel immune to the death. Consequently, they often engage in risky behaviors, such as substance use, unsafe sexual behavior, and reckless driving thinking they are invincible.

Early Adulthood: In adulthood, there are differences in the level of fear and anxiety concerning death experienced by those in different age groups. For those in early adulthood, their overall lower rate of death is a significant factor in their lower rates of death anxiety. Individuals in early adulthood typically expect a long life ahead of them, and consequently do not think about, nor worry about death.

Middle Adulthood: Those in middle adulthood report more fear of death than those in either early and late adulthood. The caretaking responsibilities for those in middle adulthood is a significant factor in their fears. As mentioned previously, middle adults often provide assistance for both their children and parents, and they feel anxiety about leaving them to care for themselves.

Late Adulthood: Contrary to the belief that because they are so close to death, they must fear death, those in late adulthood have lower fears of death than other adults. Why would this occur? First, older adults have fewer caregiving responsibilities and are not worried about leaving family members on their own. They also have had more time to complete activities they had planned in their lives, and they realize that the future will not provide as many opportunities for them. Additionally, they have less anxiety because they have already experienced the death of loved ones and have become accustomed to the likelihood of death. It is not death itself that concerns those in late adulthood; rather, it is having control over how they die.

Media Attributions

- 022-SocialDeath

- 023-USDeaths2 adapted by Ashlyne O'Neil

- 024-CanadaDeaths2 adapted by Ashlyne O'Neil

- Graph Causes of death worldwide 2017

- 024-MelancholyTeen

- 024-OlderAdults2

the permanent cessation of physical and mental processes in an organism. In the United States in the early 1980s, the American Medical Association and the American Bar Association drafted and approved the Uniform Determination of Death Act, in which death is defined as either the irreversible cessation of core physiological functioning (i.e., spontaneous circulatory and respiratory functions) or the irreversible loss of cerebral functioning (i.e., brain death). Given the emergence of sophisticated technologies for cardiopulmonary support, brain death is more often considered the essential determining factor, particularly within the legal profession.

1. a pattern of group behavior that ignores the presence or existence of a person within the group. Social death occurs in situations in which verbal and nonverbal communication would be expected to include all participants but in which one or more individuals are excluded. See shunning; ostracism.

2. the social effect of individuals’ reactions to a living person as if he or she is dead, as sometimes seen among people in the presence of a comatose patient or someone with severe dementia.