24 Psychosocial Development in Young Adulthood

Temperament and Personality in Adulthood

Temperament is defined as the innate characteristics of the infant, including mood, activity level, and emotional reactivity, noticeable soon after birth. Does one’s temperament remain stable through the lifespan? Do shy and inhibited babies grow up to be shy adults, while the sociable child continues to be the life of the party? Like most developmental research the answer is more complicated than a simple yes or no. Chess and Thomas (1987), who identified children as easy, difficult, slow-to-warm-up or blended, found that children identified as easy grew up to became well-adjusted adults, while those who exhibited a difficult temperament were not as well-adjusted as adults. Jerome Kagan (2002) has studied the temperamental category of inhibition to the unfamiliar in children. Infants exposed to unfamiliarity reacted strongly to the stimuli and cried loudly, pumped their limbs, and had an increased heart rate. Research has indicated that these highly reactive children show temperamental stability into early childhood, and Bohlin and Hagekull (2009) found that shyness in infancy was linked to social anxiety in adulthood.

An important aspect of this research on inhibition was looking at the response of the amygdala, which is important for fear and anxiety, especially when confronted with possible threatening events in the environment. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRIs) young adults identified as strongly inhibited toddlers showed heightened activation of the amygdala when compared to those identified as uninhibited toddlers (Davidson & Begley, 2012).

The research does seem to indicate that temperamental stability holds for many individuals through the lifespan, yet we know that one’s environment can also have a significant impact. Recall from our discussion on epigenesis or how environmental factors are thought to change gene expression by switching genes on and off. Many cultural and environmental factors can affect one’s temperament, including supportive versus abusive child-rearing, socioeconomic status, stable homes, illnesses, teratogens, etc. Additionally, individuals often choose environments that support their temperament, which in turn further strengthens them (Cain, 2012). In summary, because temperament is genetically driven, genes appear to be the major reason why temperament remains stable into adulthood. In contrast, the environment appears mainly responsible for any change in temperament (Clark & Watson, 1999).

Everybody has their own unique personality; that is, their characteristic manner of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating to others (John, Robins, & Pervin, 2008). Personality traits refer to these characteristic, routine ways of thinking, feeling, and relating to others. Personality integrates one’s temperament with cultural and environmental influences. Consequently, there are signs or indicators of these traits in childhood, but they become particularly evident when the person is an adult. Personality traits are integral to each person’s sense of self, as they involve what people value, how they think and feel about things, what they like to do, and, basically, what they are like most every day throughout much of their lives.

Five-Factor Model: There are hundreds of different personality traits, and all of these traits can be organized into the broad dimensions referred to as the Five-Factor Model (John, Naumann, & Soto, 2008). These five broad domains include: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (Think OCEAN to remember). This applies to traits that you may use to describe yourself. Table 4.24.1 provides illustrative traits for low and high scores on the five domains of this model of personality.

| Dimension | Description | Examples of behaviours predicted by the trait |

| Openness to experience | A general appreciation for art, emotion, adventure, unusual ideas, imagination, curiosity, and variety of experience | Individuals who are highly open to experience tend to have distinctive and unconventional decorations in their home. They are also likely to have books on a wide variety of topics, a diverse music collection, and works of art on display. |

| Conscientiousness | A tendency to show self- discipline, act dutifully, and aim for achievement | Individuals who are conscientious have a preference for planned rather than spontaneous behavior. |

| Extraversion | The tendency to experience positive emotions and to seek out stimulation and the company of others | Extroverts enjoy being with people. In groups they like to talk, assert themselves, and draw attention to themselves. |

| Agreeableness | A tendency to be compassionate and cooperative rather than suspicious and antagonistic toward others; reflects individual differences in general concern for social harmony | Agreeable individuals value getting along with others. They are generally considerate, friendly, generous, helpful, and willing to compromise their interests with those of others. |

| Neuroticism | The tendency to experience negative emotions, such as anger, anxiety, or depression; sometimes called “emotional instability” | Those who score high in neuroticism are more likely to interpret ordinary situations as threatening and minor frustrations as hopelessly difficult. They may have trouble thinking clearly, making decisions, and coping effectively with stress. |

Does personality change throughout adulthood? Previously the answer was no, but contemporary research shows that although some people’s personalities are relatively stable over time, others’ are not Lucas & Donnellan, 2011; Roberts & Mroczek, 2008). Longitudinal studies reveal average changes during adulthood in the expression of some traits (e.g., neuroticism and openness decrease with age and conscientiousness increases) and individual differences in these patterns due to idiosyncratic life events (e.g., divorce, illness). Longitudinal research also suggests that adult personality traits, such as conscientiousness, predict important life outcomes including job success, health, and longevity (Friedman et al., 1993; Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007).

The Harvard Health Letter (2012) identifies research correlations between conscientiousness and lower blood pressure, lower rates of diabetes and stroke, fewer joint problems, being less likely to engage in harmful behaviors, being more likely to stick to healthy behaviors, and more likely to avoid stressful situations. Conscientiousness also appears related to career choices, friendships, and stability of marriage. Lastly, a person possessing both self-control and organizational skills, both related to conscientiousness, may withstand the effects of aging better and have stronger cognitive skills than one who does not possess these qualities.

Attachment in Young Adulthood

Hazan and Shaver (1987) described the attachment styles of adults, using the same three general categories proposed by Ainsworth’s research on young children; secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent. Hazan and Shaver developed three brief paragraphs describing the three adult attachment styles. Adults were then asked to think about romantic relationships they were in and select the paragraph that best described the way they felt, thought, and behaved in these relationships (See Table 4.24.2).

| Which of the following best describes you in your romantic relationships? | |

| Secure | I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t often worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me. |

| Avoidant | I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, love partners want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being. |

| Anxious/Ambivalent | I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me or won’t stay with me. I want to merge completely with another person, and this sometimes scares people away. |

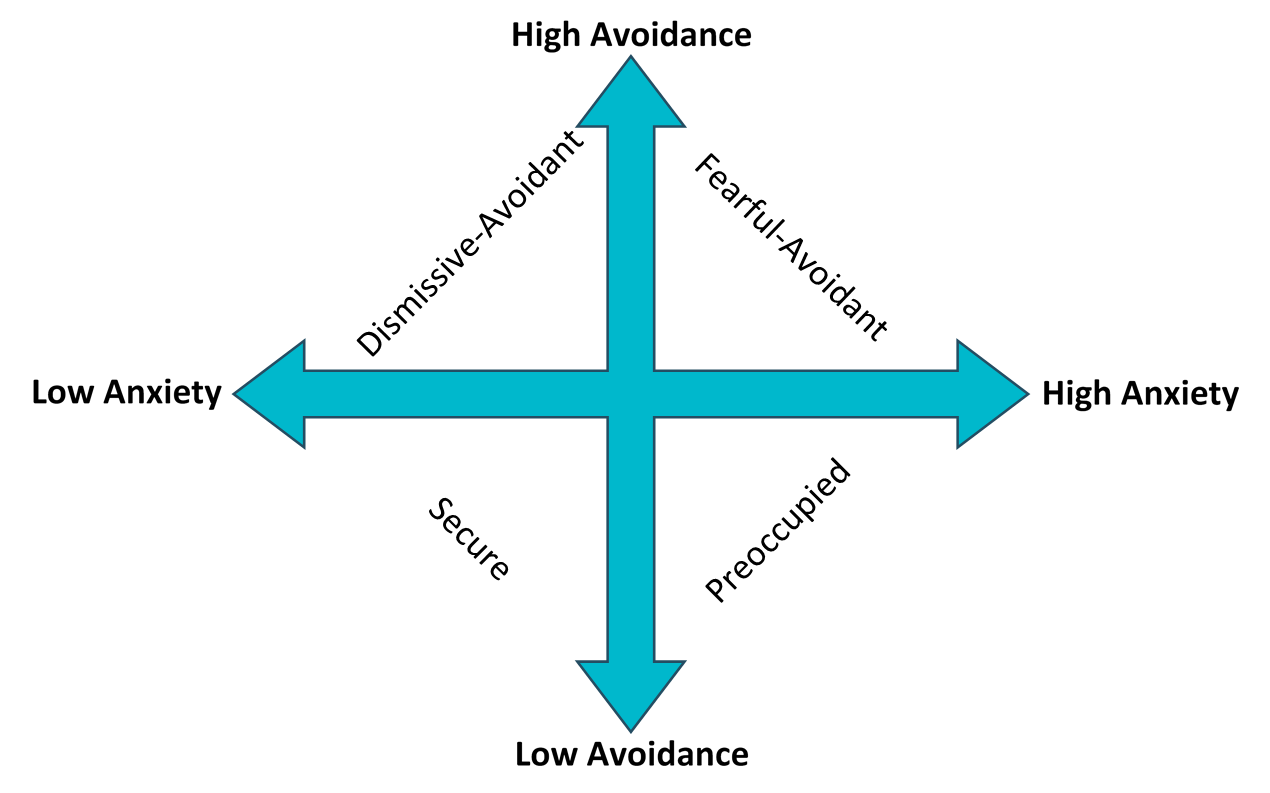

Bartholomew (1990) challenged the categorical view of attachment in adults and suggested that adult attachment was best described as varying along two dimensions; attachment related-anxiety and attachment-related avoidance. Attachment-related anxiety refers to the extent to which an adult worries about whether their partner really loves them. Those who score high on this dimension fear that their partner will reject or abandon them (Fraley, Hudson, Heffernan, & Segal, 2015). Attachment-related avoidance refers to whether an adult can open up to others, and whether they trust and feel they can depend on others. Those who score high on attachment- related avoidance are uncomfortable with opening up and may fear that such dependency may limit their sense of autonomy (Fraley et al., 2015). According to Bartholomew (1990) this would yield four possible attachment styles in adults; secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful- avoidant (see Image 4.24.1)

Securely attached adults score lower on both dimensions. They are comfortable trusting their partners and do not worry excessively about their partner’s love for them. Adults with a dismissing style score low on attachment-related anxiety, but higher on attachment-related avoidance. Such adults dismiss the importance of relationships. They trust themselves, but do not trust others, thus do not share their dreams, goals, and fears with others. They do not depend on other people, and feel uncomfortable when they have to do so.

Those with a preoccupied attachment are low in attachment-related avoidance, but high in attachment-related anxiety. Such adults are often prone to jealousy and worry that their partner does not love them as much as they need to be loved. Adults whose attachment style is fearful-avoidant score high on both attachment-related avoidance and attachment-related anxiety. These adults want close relationships, but do not feel comfortable getting emotionally close to others. They have trust issues with others and often do not trust their own social skills in maintaining relationships.

Research on attachment in adulthood has found that:

- Adults with insecure attachments report lower satisfaction in their relationships (Butzer, & Campbell, 2008; Holland, Fraley, & Roisman, 2012).

- Those high in attachment-related anxiety report more daily conflict in their relationships (Campbell, Simpson, Boldry, & Kashy, 2005).

- Those with avoidant attachment exhibit less support to their partners (Simpson, Rholes, Oriña, & Grich, 2002).

- Young adults show greater attachment-related anxiety than do middle-aged or older adults (Chopik, Edelstein, & Fraley, 2013).

- Some studies report that young adults show more attachment-related avoidance (Schindler, Fagundes, & Murdock, 2010), while other studies find that middle-aged adults show higher avoidance than younger or older adults (Chopik et al., 2013).

- Young adults with more secure and positive relationships with their parents make the transition to adulthood more easily than do those with more insecure attachments (Fraley, 2013).

Do people with certain attachment styles attract those with similar styles?

When people are asked what kinds of psychological or behavioral qualities they are seeking in a romantic partner, a large majority of people indicate that they are seeking someone who is kind, caring, trustworthy, and understanding, that is the kinds of attributes that characterize a “secure” caregiver (Chappell & Davis, 1998). However, we know that people do not always end up with others who meet their ideals. Are secure people more likely to end up with secure partners, and, vice versa, are insecure people more likely to end up with insecure partners? The majority of the research that has been conducted to date suggests that the answer is “yes.” Frazier, Byer, Fischer, Wright, and DeBord (1996) studied the attachment patterns of more than 83 heterosexual couples and found that, if the man was relatively secure, the woman was also likely to be secure.

One important question is whether these findings exist because (a) secure people are more likely to be attracted to other secure people, (b) secure people are likely to create security in their partners over time, or (c) some combination of these possibilities. Existing empirical research strongly supports the first alternative. For example, when people have the opportunity to interact with individuals who vary in security in a speed-dating context, they express a greater interest in those who are higher in security than those who are more insecure (McClure, Lydon, Baccus, & Baldwin, 2010). However, there is also some evidence that people’s attachment styles mutually shape one another in close relationships. For example, in a longitudinal study, Hudson, Fraley, Vicary, and Brumbaugh (2012) found that, if one person in a relationship experienced a change in security, his or her partner was likely to experience a change in the same direction.

Do early experiences as children shape adult attachment?

The majority of research on this issue is retrospective; that is, it relies on adults’ reports of what they recall about their childhood experiences. This kind of work suggests that secure adults are more likely to describe their early childhood experiences with their parents as being supportive, loving, and kind (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). A number of longitudinal studies are emerging that demonstrate prospective associations between early attachment experiences and adult attachment styles and/or interpersonal functioning in adulthood. For example, Fraley, Roisman, Booth-LaForce, Owen, and Holland (2013) found in a sample of more than 700 individuals studied from infancy to adulthood that maternal sensitivity across development prospectively predicted security at age 18. Simpson, Collins, Tran, and Haydon (2007) found that attachment security, assessed in infancy in the strange situation, predicted peer competence in grades one to three, which, in turn, predicted the quality of friendship relationships at age 16, which, in turn, predicted the expression of positive and negative emotions in their adult romantic relationships at ages 20 to 23.

It is easy to come away from such findings with the mistaken assumption that early experiences “determine” later outcomes. To be clear: Attachment theorists assume that the relationship between early experiences and subsequent outcomes is probabilistic, not deterministic. Having supportive and responsive experiences with caregivers early in life is assumed to set the stage for positive social development. But that does not mean that attachment patterns are set in stone. In short, even if an individual has far from optimal experiences in early life, attachment theory suggests that it is possible for that individual to develop well-functioning adult relationships through a number of corrective experiences, including relationships with siblings, other family members, teachers, and close friends. Security is best viewed as a culmination of a person’s attachment history rather than a reflection of his or her early experiences alone. Those early experiences are considered important, not because they determine a person’s fate, but because they provide the foundation for subsequent experiences.

Relationships with Parents and Siblings

In early adulthood the parent-child relationship has to transition toward a relationship between two adults. This involves a reappraisal of the relationship by both parents and young adults. One of the biggest challenges for parents, especially during emerging adulthood, is coming to terms with the adult status of their children. Aquilino (2006) suggests that parents who are reluctant or unable to do so may hinder young adults’ identity development. This problem becomes more pronounced when young adults still reside with their parents. Arnett (2004) reported that leaving home often helped promote psychological growth and independence in early adulthood.

Sibling relationships are one of the longest-lasting bonds in people’s lives. Yet, there is little research on the nature of sibling relationships in adulthood (Aquilino, 2006). What is known is that the nature of these relationships change, as adults have a choice as to whether they will maintain a close bond and continue to be a part of the life of a sibling. Siblings must make the same reappraisal of each other as adults, as parents have to with their adult children. Research has shown a decline in the frequency of interactions between siblings during early adulthood, as presumably peers, romantic relationships, and children become more central to the lives of young adults. Aquilino (2006) suggests that the task in early adulthood may be to maintain enough of a bond so that there will be a foundation for this relationship in later life. Those who are successful can often move away from the “older-younger” sibling conflicts of childhood, toward a more equal relationship between two adults. Siblings that were close to each other in childhood are typically close in adulthood (Dunn, 1984, 2007), and in fact, it is unusual for siblings to develop closeness for the first time in adulthood. Overall, the majority of adult sibling relationships are close (Cicirelli, 2009).

Erikson: Intimacy vs. Isolation

Erikson’s (1950, 1968) sixth stage focuses on establishing intimate relationships or risking social isolation. Intimate relationships are more difficult if one is still struggling with identity. Achieving a sense of identity is a life-long process, as there are periods of identity crisis and stability. However, once identity is established intimate relationships can be pursued. These intimate relationships include acquaintances and friendships, but also the more important close relationships, which are the long-term romantic relationships that we develop with another person, for instance, in a marriage (Hendrick & Hendrick, 2000).

Factors influencing Attraction

Because most of us enter into a close relationship at some point, it is useful to know what psychologists have learned about the principles of liking and loving. A major interest of psychologists is the study of interpersonal attraction, or what makes people like, and even love, each other.

Similarity

One important factor in attraction is a perceived similarity in values and beliefs between the partners (Davis & Rusbult, 2001). Similarity is important for relationships because it is more convenient if both partners like the same activities and because similarity supports one’s values. We can feel better about ourselves and our choice of activities if we see that our partner also enjoys doing the same things that we do. Having others like and believe in the same things we do makes us feel validated in our beliefs. This is referred to as consensual validation and is an important aspect of why we are attracted to others.

Self-Disclosure

Liking is also enhanced by self-disclosure, the tendency to communicate frequently, without fear of reprisal, and in an accepting and empathetic manner. Friends are friends because we can talk to them openly about our needs and goals and because they listen and respond to our needs (Reis & Aron, 2008). However, self-disclosure must be balanced. If we open up about our concerns that are important to us, we expect our partner to do the same in return. If the self-disclosure is not reciprocal, the relationship may not last.

Proximity

Another important determinant of liking is proximity, or the extent to which people are physically near us. Research has found that we are more likely to develop friendships with people who are nearby, for instance, those who live in the same dorm that we do, and even with people who just happen to sit nearer to us in our classes (Back, Schmukle, & Egloff, 2008).

Proximity has its effect on liking through the principle of mere exposure, which is the tendency to prefer stimuli (including, but not limited to people) that we have seen more frequently. The effect of mere exposure is powerful and occurs in a wide variety of situations. Infants tend to smile at a photograph of someone they have seen before more than they smile at a photograph of someone they are seeing for the first time (Brooks-Gunn & Lewis, 1981), and people prefer side- to-side reversed images of their own faces over their normal (nonreversed) face, whereas their friends prefer their normal face over the reversed one (Mita, Dermer, & Knight, 1977). This is expected on the basis of mere exposure, since people see their own faces primarily in mirrors, and thus are exposed to the reversed face more often.

Mere exposure may well have an evolutionary basis. We have an initial fear of the unknown, but as things become more familiar they seem more similar and safe, and thus produce more positive affect and seem less threatening and dangerous (Harmon-Jones & Allen, 2001; Freitas, Azizian, Travers, & Berry, 2005). When the stimuli are people, there may well be an added effect. Familiar people become more likely to be seen as part of the ingroup rather than the outgroup, and this may lead us to like them more. Leslie Zebrowitz and her colleagues found that we like people of our own race in part because they are perceived as similar to us (Zebrowitz, Bornstad, & Lee, 2007).

Friendships

In our twenties, intimacy needs may be met in friendships rather than with partners. This is especially true in the United States today as many young adults postpone making long-term commitments to partners, either in marriage or in cohabitation. The kinds of friendships shared by women tend to differ from those shared by men (Tannen, 1990). Friendships between men are more likely to involve sharing information, providing solutions, or focusing on activities rather than discussion problems or emotions. Men tend to discuss opinions or factual information or spend time together in an activity of mutual interest. Friendships between women are more likely to focus on sharing weaknesses, emotions, or problems. Women talk about difficulties they are having in other relationships and express their sadness, frustrations, and joys. These differences in approaches lead to problems when men and women come together. She may want to vent about a problem she is having; he may want to provide a solution and move on to some activity. But when he offers a solution, she thinks he does not care.

Friendships between men and women become more difficult because of the unspoken question about whether the friendships will lead to a romantic involvement. Consequently, friendships may diminish once a person has a partner or single friends may be replaced with couple friends.

Love

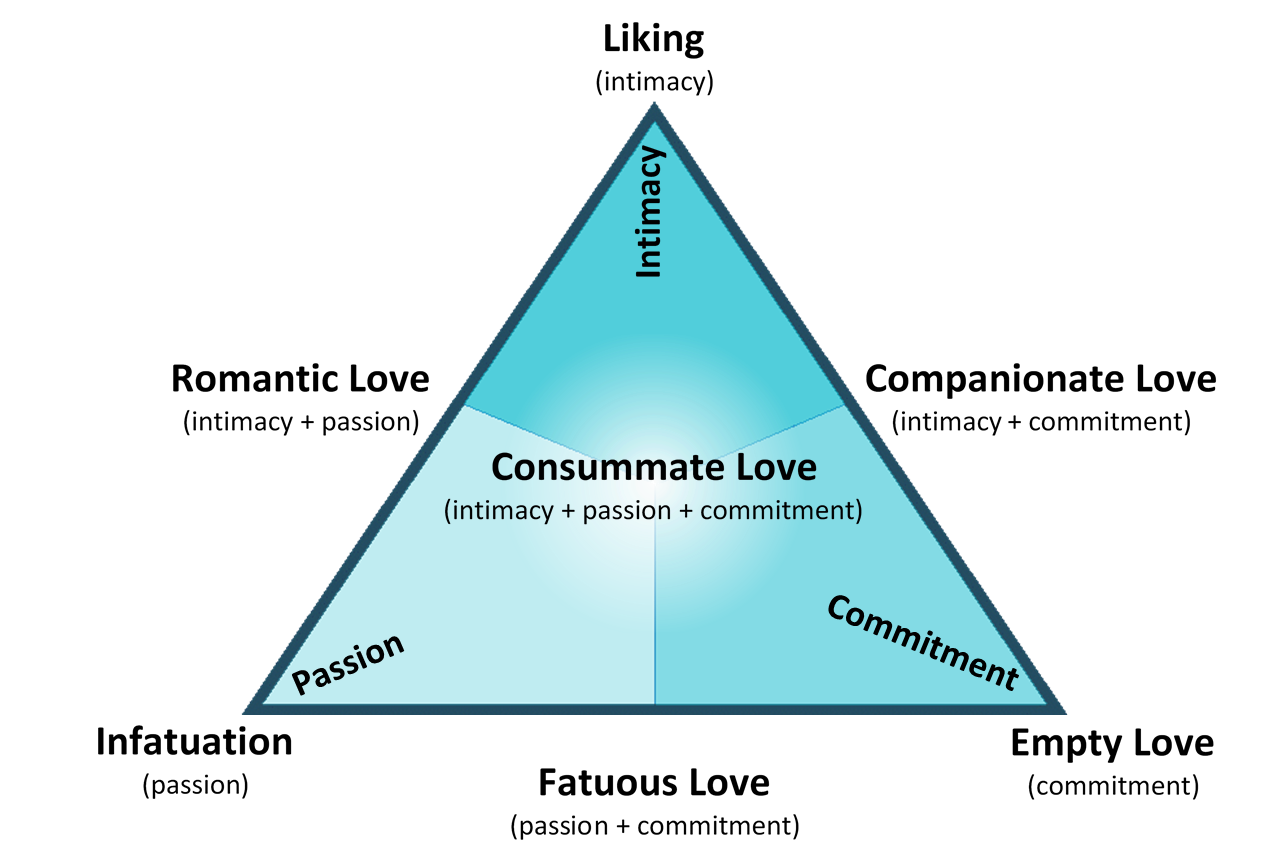

Sternberg (1988) suggests that there are three main components of love: Passion, intimacy, and commitment (see Figure 7.24). Love relationships vary depending on the presence or absence of each of these components. Passion refers to the intense, physical attraction partners feel toward one another. Intimacy involves the ability the share feelings, personal thoughts and psychological closeness with the other. Commitmentis the conscious decision to stay together. Passion can be found in the early stages of a relationship, but intimacy takes time to develop because it is based on knowledge of the partner. Once intimacy has been established, partners may resolve to stay in the relationship. Although many would agree that all three components are important to a relationship, many love relationships do not consist of all three. Let’s look at other possibilities.

Liking: In this relationship, intimacy or knowledge of the other and a sense of closeness is present. Passion and commitment, however, are not. Partners feel free to be themselves and disclose personal information. They may feel that the other person knows them well and can be honest with them and let them know if they think the person is wrong. These partners are friends. However, being told that your partner “thinks of you as a friend” can be a devastating blow if you are attracted to them and seeking a romantic involvement.

Infatuation: Perhaps, this is Sternberg’s version of “love at first sight”. Infatuation consists of an immediate, intense physical attraction to someone. A person who is infatuated finds it hard to think of anything but the other person. Brief encounters are played over and over in one’s head; it may be difficult to eat and there may be a rather constant state of arousal. Infatuation is rather short-lived, however, lasting perhaps only a matter of months or as long as a year or so. It tends to be based on physical attraction and an image of what one “thinks” the other is all about.

Fatuous Love: However, some people who have a strong physical attraction push for commitment early in the relationship. Passion and commitment are aspects of fatuous love. There is no intimacy and the commitment is premature. Partners rarely talk seriously or share their ideas. They focus on their intense physical attraction and yet one, or both, is also talking of making a lasting commitment. Sometimes this is out of a sense of insecurity and a desire to make sure the partner is locked into the relationship.

Empty Love: This type of love may be found later in a relationship or in a relationship that was formed to meet needs other than intimacy or passion, including financial needs, childrearing assistance, or attaining/maintaining status. Here the partners are committed to staying in the relationship for the children, because of a religious conviction, or because there are no alternatives. However, they do not share ideas or feelings with each other and have no physical attraction for one another.

Romantic Love: Intimacy and passion are components of romantic love, but there is no commitment. The partners spend much time with one another and enjoy their closeness, but have not made plans to continue. This may be true because they are not in a position to make such commitments or because they are looking for passion and closeness and are afraid it will die out if they commit to one another and start to focus on other kinds of obligations.

Companionate Love: Intimacy and commitment are the hallmarks of companionate love. Partners love and respect one another and they are committed to staying together. However, their physical attraction may have never been strong or may have just died out over time. Nevertheless, partners are good friends and committed to one another.

Consummate Love: Intimacy, passion, and commitment are present in consummate love. This is often perceived by western cultures as “the ideal” type of love. The couple shares passion; the spark has not died, and the closeness is there. They feel like best friends, as well as lovers, and they are committed to staying together.

The text in this chapter is all directly from Lally & Valentine-French (2017). Two photographs have been chosen and substituted by O’Neil, McCarthy, and Williams.

Media Attributions

- 046-AttachmentStyles

- 048-FamilyMeal © The Big Lunch is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Heading south by the dawn’s light. © Jamie McCaffrey is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- 047-SternbergsLove

the basic foundation of personality, usually assumed to be biologically determined and present early in life, including such characteristics as energy level, emotional responsiveness, demeanor, mood, response tempo, behavioral inhibition, and willingness to explore.

the theory that characteristics of an organism, both physical and behavioral, arise from an interaction between genetic and environmental influences rather than from one or the other.

the enduring configuration of characteristics and behavior that comprises an individual’s unique adjustment to life, including major traits, interests, drives, values, self-concept, abilities, and emotional patterns. Personality is generally viewed as a complex, dynamic integration or totality shaped by many forces, including hereditary and constitutional tendencies; physical maturation; early training; identification with significant individuals and groups; culturally conditioned values and roles; and critical experiences and relationships. Various theories explain the structure and development of personality in different ways, but all agree that personality helps determine behavior.

a model of personality in which five dimensions of individual differences—extraversion, neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness to experience—are viewed as core personality structures. Unlike the Big Five personality model, which views the five personality dimensions as descriptions of behavior and treats the five-dimensional structure as a taxonomy of individual differences, the FFM views the factors as psychological entities with causal force. The two models are frequently and incorrectly conflated in the scientific literature, without regard for their distinctly different emphases.

the interest in and liking of one individual by another, or the mutual interest and liking between two or more individuals.

the act of revealing personal or private information about one’s self to other people. In relationships research, self-disclosure has been shown to foster feelings of closeness and intimacy.

the finding that individuals show an increased preference (or liking) for a stimulus as a consequence of repeated exposure to that stimulus. This effect is most likely to occur when there is no preexisting negative attitude toward the stimulus object, and it tends to be strongest when the person is not consciously aware of the stimulus presentations.

1. an intense, driving, or overwhelming feeling or conviction. Passion is often contrasted with emotion, in that passion affects a person unwillingly.

2. intense sexual desire.

an interpersonal state of extreme emotional closeness such that each party’s personal space can be entered by any of the other parties without causing discomfort to that person. Intimacy characterizes close, familiar, and usually affectionate or loving personal relationships and requires the parties to have a detailed knowledge or deep understanding of each other.

obligation or devotion to a person, relationship, task, cause, or other entity or action. In relationships, this is the conscious decision to stay together.