19 Health and Physical Development for Young Adults

The Physiological Peak

People in their mid-twenties to mid-forties are considered to be in early adulthood. By the time we reach early adulthood, our physical maturation is complete, although our height and weight may increase slightly. Those in their early twenties are probably at the peak of their physiological development, including muscle strength, reaction time, sensory abilities, and cardiac functioning. The reproductive system, motor skills, strength, and lung capacity are all operating at their best. Most professional athletes are at the top of their game during this stage, and many women have children in the early-adulthood years (Boundless, 2016).

The aging process actually begins during early adulthood. Around the age of 30, many changes begin to occur in different parts of the body. For example, the lens of the eye starts to stiffen and thicken, resulting in changes in vision (usually affecting the ability to focus on close objects). Sensitivity to sound decreases; this happens twice as quickly for men as for women. Hair can start to thin and become gray around the age of 35, although this may happen earlier for some individuals and later for others. The skin becomes drier and wrinkles start to appear by the end of early adulthood. This includes a decline in response time and the ability to recover quickly from physical exertion. The immune system also becomes less adept at fighting off illness, and reproductive capacity starts to decline (Boundless, 2016).

Obesity

Although at the peak of physical health, a concern for early adults is the current rate of obesity. Results from the 2015 National Center for Health Statistics indicate that an estimated 70.7% of U.S. adults aged 20 and over are overweight and 37.9% are obese (CDC, 2015b). Body mass index (BMI), expressed as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2), is commonly used to classify overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9), obesity (BMI greater than or equal to 30.0), and extreme obesity (BMI greater than or equal to 40.0). The 2015 statistics are an increase from the 2013-2014 statistics that indicated that an estimated 35.1% were obese, and 6.4% extremely obese (Fryar, Carroll, & Ogden, 2014). In 2003-2004, 32% of American adults were identified as obese. The CDC also indicated that one’s 20s are the prime time to gain weight as the average person gains one to two pounds per year from early adulthood into middle adulthood. The average man in his 20s weighs around 185 pounds and by his 30s weighs approximately 200 pounds. The average American woman weights 162 pounds in her 20s and 170 pounds in her 30s. (Material in this chapter up to this point taken directly from Lally and Valentine-French (2017)

The American obesity crisis is also reflected in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2018) and worldwide (Wighton, 2016). In 2018, Statistics Canada reported that 2017 20% of those from 18 to 39 were obese and overall 27% of Canadians were obese. In contrast with the U.S. figures the overall rate of obesity in Canada has been relatively unchanging, at least from 2007 to 2017. In 2014, global obesity rates for men were measured at 10.8% and among women 14.9%. This translates to 266 million obese men and 375 million obese women in the world, and more people were identified as obese than underweight. Although obesity is seen throughout the world, more obese men and women live in China and the USA than in any other country. See the following interactive map for more information on adult obesity around the world: https://www.worldobesitydata.org/map/overview-adults#

Material in above paragraph is directly from Lally & Valentine-French (2017) with the exception of material on Canada obtained by Baird and material for table or figure by O’Neil, McCarthy, & Williams.

*Causes of Obesity

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2016), obesity originates from a complex set of contributing factors, including one’s environment, behavior, and genetics. Societal factors include culture, education, food marketing and promotion, the quality of food, and the physical activity environment available. Behaviors leading to obesity include diet, the amount of physical activity, and medication use. Lastly, there does not appear to be a single gene responsible for obesity. Rather, research has identified variants in several genes that may contribute to obesity by increasing hunger and food intake. Another genetic explanation is the mismatch between today’s environment and “energy-thrifty genes” that multiplied in the distant past, when food sources were unpredictable. The genes that helped our ancestors survive occasional famines are now being challenged by environments in which food is plentiful all the time. Overall, obesity most likely results from complex interactions among the environment and multiple genes.

Obesity Health Consequences

Obesity is considered to be one of the leading causes of death in the United States and worldwide. Additionally, the medical care costs of obesity in the United States were estimated to be $147 billion in 2008. According to the CDC (2016) compared to those with a normal or healthy weight, people who are obese are at increased risk for many serious diseases and health conditions including:

- All-causes of death (mortality)

- High blood pressure (Hypertension)

- High LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, or high levels of triglycerides (Dyslipidemia)

- Type 2 diabetes

- Coronary heart disease

- Stroke

- Gallbladder disease

- Osteoarthritis (a breakdown of cartilage and bone within a joint)

- Sleep apnea and breathing problems

- Some cancers (endometrial, breast, colon, kidney, gallbladder, and liver)

- Low quality of life

- Mental illness such as clinical depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders

- Body pain and difficulty with physical functioning

A Healthy, But Risky Time

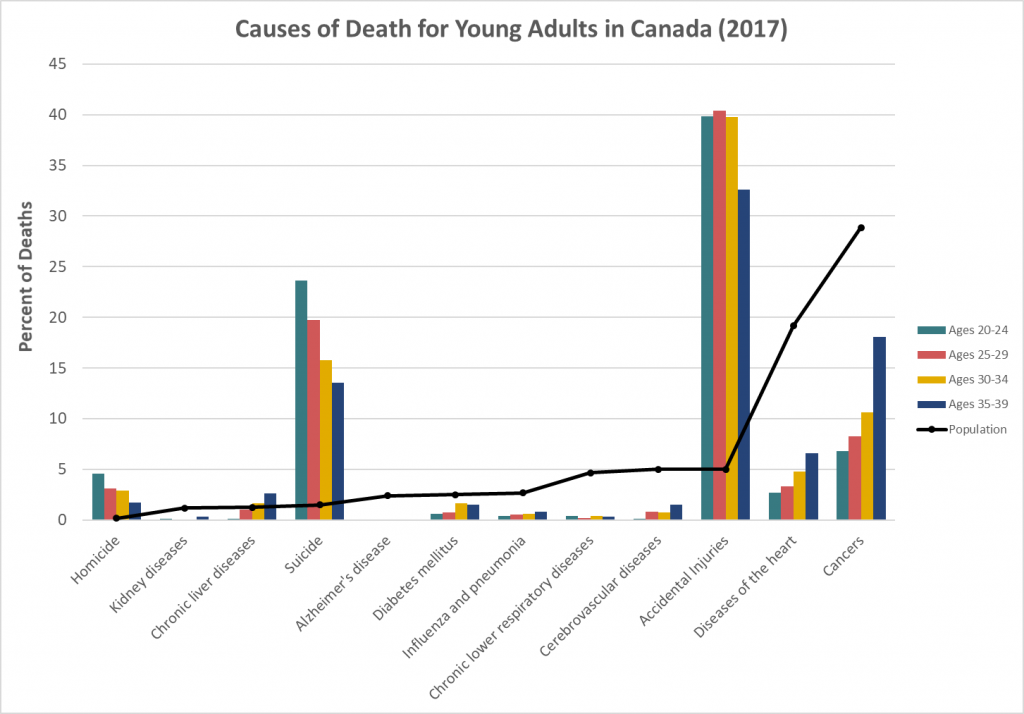

Doctor’s visits are less frequent in early adulthood than for those in midlife and late adulthood and are necessitated primarily by injury and pregnancy (Berger, 2005). However, the top five causes of death in emerging and early adulthood are non-intentional injury (including motor vehicle accidents), homicide, and suicide with cancer and heart disease completing the list (Heron, & Smith, 2007). Rates of violent death (homicide, suicide, and accidents) are highest among young adult males, and vary by race and ethnicity. Rates of violent death are higher in the United States than in Canada, Mexico, Japan, and other selected countries. Males are 3 times more likely to die in auto accidents than are females (Frieden, 2011).

*Material from here to here taken directly from Lally & Valentine-French (2017). Figure below is provided by O’Neil, McCarthy, & Williams.

*Alcohol Abuse

A significant contributing factor to risky behavior is alcohol. According to the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), 2016) 88% of people ages 18 or older reported that they drank alcohol at some point in their lifetime; 71% reported that they drank in the past year; and 57% reported drinking in the past month. Additionally, 6.7% reported that they engaged in heavy drinking in the past month. Heavy drinking is defined as drinking five or more drinks on the same occasion on each of five or more days in the past 30 days. Nearly 88,000 people (approximately 62,000 men and 26,000 women) die from alcohol-related causes annually, making it the fourth leading preventable cause of death in the United States. In 2014, alcohol-impaired driving fatalities accounted for 9,967 deaths (31% of overall driving fatalities).

The NIAAA defines binge drinking when blood alcohol concentration levels reach 0.08 g/dL. This typically occurs after four drinks for women and five drinks for men in approximately two hours. In 2014, 25% of people ages 18 or older reported that they engaged in binge drinking in the past month. According to the NIAAA (2015) “Binge drinking poses serious health and safety risks, including car crashes, drunk-driving arrests, sexual assaults, and injuries. Over the long term, frequent binge drinking can damage the liver and other organs,” (p. 1).

Alcohol and College Students

Results from the 2014 survey demonstrated a difference between the amount of alcohol consumed by college students and those of the same age who are not in college (NIAAA, 2016). Specifically, 60% of full-time college students’ ages 18–22 drank alcohol in the past month compared with 51.5% of other persons of the same age not in college. In addition, 38% of college students’ ages 18–22 engaged in binge drinking; that is, five or more drinks on one occasion in the past month, compared with 33.5% of other persons of the same age. Lastly, 12% of college students’ (ages 18–22) engaged in heavy drinking; that is, binge drinking on five or more occasions per month, in the past month. This compares with 9.5% of other emerging adults not in college.

The consequences for college drinking are staggering, and the NIAAA (2016) estimates that each year the following occur:

- 1,825 college students between the ages of 18 and 24 die from alcohol-related unintentional injuries, including motor-vehicle crashes.

- 696,000 students between the ages of 18 and 24 are assaulted by another student who has been drinking.

- Roughly 1 in 5 college students meet the criteria for an Alcohol Use Disorder.

- About 1 in 4 college students report academic consequences from drinking, including missing class, falling behind in class, doing poorly on exams or papers, and receiving lower grades overall. (p. 1)

- 97,000 students between the ages of 18 and 24 report experiencing alcohol-related sexual assault or date rape.

The role alcohol plays in predicting acquaintance rape on college campuses is of particular concern. “Alcohol use in one the strongest predictors of rape and sexual assault on college campuses,” (Carroll, 2016, p. 454). Krebs, Lindquist, Warner, Fisher and Martin (2009) found that over 80% of sexual assaults on college campuses involved alcohol. Being intoxicated increases a female’s risk of being the victim of date or acquaintance rape (Carroll,

2007). Females are more likely to blame themselves and to be blamed by others if they were intoxicated when raped. College students view perpetrators who were drinking as less responsible, and victims who were drinking as more responsible for the assaults (Untied, Orchowski, Mastroleo, & Gidycz, 2012).

Factors Affecting College Students’ Drinking: Several factors associated with college life affect a student’s involvement with alcohol (NIAAA, 2015). These include the pervasive availability of alcohol, inconsistent enforcement of underage drinking laws, unstructured time, coping with stressors, and limited interactions with parents and other adults. Due to social pressures to conform and expectations when entering college, the first six weeks of freshman year are an especially susceptible time for students. Additionally, more drinking occurs in colleges with active Greek systems and athletic programs. Alcohol consumption is lowest among students living with their families and commuting, while it is highest among those living in fraternities and sororities.

College Strategies to Curb Drinking: Strategies to address college drinking involve the individual-level and campus community as a whole. Identifying at-risk groups, such as first year students, members of fraternities and sororities, and athletes has proven helpful in changing students’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavior regarding alcohol (NIAAA, 2015). Interventions include education and awareness programs, as well as intervention by health professionals. At the college-level, reducing the availability of alcohol has proven effective by decreasing both consumption and negative consequences.

Non-Alcohol Substance Use: In the U.S. illicit drug use peaks between the ages of 19 and 22 and then begins to decline. Additionally, 25% of those who smoke cigarettes, 33% of those who smoke marijuana, and 70% of those who abuse cocaine began using after age 17 (Volkow, 2004). Emerging adults (18 to 25) are the largest abusers of prescription opioid pain relievers, anti-anxiety medications, and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder medication (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2015). In 2014 more than 1700 emerging adults died from a prescription drug overdose in the U.S. This is an increase of four times since 1999. Additionally, for every death there were 119 emergency room visits.

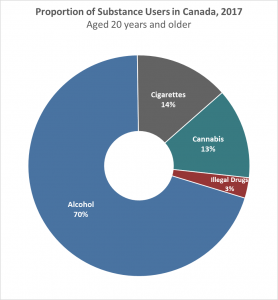

*Material from here to here taken directly from Lally & Valentine-French. Canadian material in next two paragraphs was curated by Baird and Figure at left was found and prepared by O’Neil, McCarthy, & Williams.

Canadian data (Orpana et al., 2018) show that mortality and disability related to opioid use increased dramatically from 1990 to 2014, while these rates decreased on a global level. In Canada overall effects were greater for men than women and among age groups were greatest for 25 to 29 year-olds. Although these increases in disability and death were less than those in the U.S., the authors note that Canada usually follows U.S. trends in the years following.

The 2017 Canadian Cannabis Survey indicated that 41% of people from 16 to 24 used marijuana at some level during the previous 12 months according to a report in The Globe and Mail by Anna Sharratt (Nov. 2, 2018). Dr. Abby Goldstein, a University of Toronto psychology professor noted that recent legalization offered an opportunity for societal decisions protecting students and others from the negative effects of cannabis use.

*Daily marijuana use is at the highest level in three decades in the U.S. (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2015). For those in college, 2014 data indicate that 6% of college students smoke marijuana daily, while only 2% smoked daily in 1994. For non-college students of the same age, the daily percentage is twice as high (approximately 12%). Additionally, daily cigarette smoking is lower for those in college as only 13% smoked in the past month, while for those not in college it was almost 25%.

Rates of violent death are influenced by substance use which peaks during emerging and early adulthood. Drugs impair judgment, reduce inhibitions, and alter mood, all of which can lead to dangerous behavior. Reckless driving, violent altercations, and forced sexual encounters are some examples. Drug and alcohol use increase the risk of sexually transmitted infections because people are more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior when under the influence. This includes having sex with someone who has had multiple partners, having anal sex without the use of a condom, having multiple partners, or having sex with someone whose history is unknown. Lastly, as previously discussed, drugs and alcohol ingested during pregnancy have a teratogenic effect on the developing embryo and fetus.

*Material from here to here taken directly from Lally & Valentine-French (2017). The rest of the chapter was written by Baird.

SUMMARY

As we glance back at this section on physical development and health in emerging and young adulthood, we can see again the relevance of the lifespan perspective. The opioid use crisis is a part of early twenty-first century life for those in their twenties, but not for earlier cohorts. It is not as severe in some other places around the world as it is in North America. Clearly societies have a major role in laying the ground for substance use disorders as well as in intervening.

Solving the problems raised by substance use also is best done from a lifespan perspective. We need to retain that idea of plasticity—opioid and other substance use disorders can be treated successfully at any age and need not persist through the rest of the lifespan. Recognizing that development is continuous leads to the idea that prevention efforts should start before the twenties since substance use often starts then as well as the mental health problems that can make people in their teens and twenties vulnerable to substance misuse (Greenbaum, 2019a). Psychologists and others working on innovations to treat pain and opioid use disorder find that a biopsychosocial approach is the most productive, and they suggest that our whole society needs a change in mindset from the idea that you treat pain with medicine to the idea that you treat pain with the whole panorama of approaches that affect the mind-body connection (Greenbaum). Think yoga, Tai Chi, meditation, relaxation therapy, psychoeducation, and counselling.

One way society affects problems for better or worse is the way we talk about each other and the problem, as we have discussed regarding chronological age. Researchers who study stigma and substance use advise us to use “person with an alcohol use disorder,” not “alcoholic;” “negative screen test,” not “clean;” and “medications for alcohol use disorder treatment,” not “medication-assisted treatment” (Greenbaum, 2019b).

Lifespan developmental psychologists in the American Psychological Association have compiled recommendations for maintaining and building resilience across the lifespan in their booklet entitled Life Plan for the Life Span (American Psychological Association [APA], 2018). As you probably would predict, they recommend a healthy diet, physical activity habit, and regular sleep. If you think about some of the ways we’ve talked about in which emotions can affect health, then you might predict correctly their recommendation that young adults work on their stress management and emotional regulation skills. Given how fast the health context for adult development changes, as well as our understanding of environmental influences, maybe the following recommendations also won’t surprise you. They advise that young adults should pay close attention to their physicians for information on preventive measures, that they educate themselves about prevention and health, that they develop effective advocacy skills for themselves and loved ones, and that they try to avoid harmful substances and events in the environment (APA, 2018).

Media Attributions

- 037-youngadultsfit © blackmachinex is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- 035-YoungAdultDeaths(v2)

- bingedrinking is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- 038-AdultSubstanceUse adapted by https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/181030/t001b-eng.htm