29 Health Concerns in Middle Adulthood

Heart Disease

According to the most recent National Vital Statistics Reports (Xu, Murphy, Kochanek, & Bastian, 2016) heart disease continues to be the number one cause of death for Americans as it claimed 23.5% of those who died in 2013. Heart disease develops slowly over time and typically appears in midlife (Hooker & Pressman, 2016).

It is the number two cause of death for Canadians as of 2016 (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2017). The death rate for Canadians with known heart disease fell by 23% from 2000/2001 to 2012/2013 (Public Health Agency of Canada. While heart disease remains the number one cause of death worldwide (World Health Organization, 2013), research (Dagenais et al., 2019) suggests that cancer eventually will become the primary cause of death in middle age worldwide as more and more heart attacks and strokes are prevented or successfully treated. Cancer will emerge as the number 1 cause of death sooner in higher income nations in which access to treatment for heart disease is more available (Dagenais).

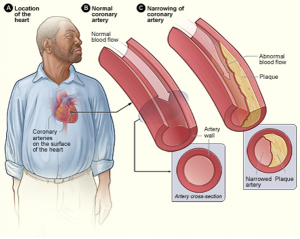

Heart disease can include heart defects and heart rhythm problems, as well as narrowed, blocked, or stiffened blood vessels referred to as cardiovascular disease. The blocked blood vessels prevent the body and heart from receiving adequate blood. Atherosclerosis, or a buildup of fatty plaque in the arteries, is the most common cause of cardiovascular disease. The plaque buildup thickens the artery walls and restricts the blood flow to organs and tissues. Cardiovascular disease can lead to a heart attack, chest pain (angina), or stroke (Mayo Clinic, 2014a). Figure 8.5 illustrates atherosclerosis.

Symptoms of cardiovascular disease differ for men and women. Males are more likely to suffer chest pain, while women are more likely to demonstrate shortness of breath, nausea, and extreme fatigue. Symptoms can also include pain in the arms, legs, neck, jaw, throat, abdomen or back (Mayo Clinic, 2014a). According to the Mayo Clinic (2014a) there are many risk factors for developing heart disease, including medical conditions, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, and obesity. Other risk factors include:

- Advanced Age

- increased risk for narrowed arteries and weakened or thickened heart muscle.

- Sex

- males are at greater risk, but a female’s risk increases after menopause.

- Family History

- increased risk, especially if male parent or brother developed heart. disease before age 55 or female parent or sister developed heart disease before age 65.

- Smoking

- nicotine constricts blood vessels and carbon monoxide damages the inner lining.

- Poor Diet

- a diet high in fat, salt, sugar, and cholesterol.

- Stress

- unrelieved stress can damage arteries and worsen other risk factors.

- Poor Hygiene

- establishing good hygiene habits can prevent viral or bacterial infections that can affect the heart. Poor dental care can also contribute to heart disease.

Complications of heart disease can include heart failure, when the heart cannot pump enough blood to the meet the body’s needs, and a heart attack, when a blood clot blocks the blood flow to the heart. This blockage can damage or destroy a part of the heart muscle, and atherosclerosis is a factor in a heart attack. Treatment for heart disease includes medication, surgery, and lifestyle changes including exercise, healthy diet, and refraining from smoking.

Sudden cardiac arrest is the unexpected loss of heart functioning, breathing, and consciousness, often caused by an arrhythmia or abnormal heartbeat. The heart beat may be too quick, too slow, or irregular. With a healthy heart, it is unlikely for a fatal arrhythmia to develop without an outside factor, such as an electric shock or illegal drugs. If not treated immediately, sudden cardiac arrest can be fatal and result in sudden cardiac death.

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a serious health problem that occurs when the blood flows with a greater force than normal. One in three American adults (70 million people) have hypertension and only half have it under control (Nwankwo, Yoon, Burt, & Gu, 2013). Hypertension can strain the heart, increase the risk of heart attack and stroke, or damage the kidneys (CDC, 2014a). Uncontrolled high blood pressure in early and middle adulthood can also damage the brain’s white matter (axons), and may be linked to cognitive problems later in life (Maillard et al., 2012). Normal blood pressure is under 120/80 as defined by the CDC in the US (see Table 8.1). About one in four Canadians from 20 to 79 has hypertension as defined by a different standard (over130/80), according to a Statistics Canada report (DeGuire et al., 2019). The first number in a blood pressure reading is the systolic pressure, which is the pressure in the blood vessels when the heart beats. The second number is the diastolic pressure, which is the pressure in the blood vessels when the heart is at rest. High blood pressure is sometimes referred to as the silent killer, as most people with hypertension experience no symptoms.

| Systolic Pressure | Diastolic Pressure | |

| Normal | Under 120 | Under 80 |

| Prehypertension (at risk) | 120-139 | 80-89 |

| Hypertension | 140 or higher | 90 or higher |

Risk factors for high blood pressure include:

- Family history of hypertension

- Diet that is too high in sodium, often found in processed foods, and too low in potassium

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Obesity

- Too much alcohol consumption

- Tobacco use, as nicotine raises blood pressure (CDC, 2014b).

Making lifestyle changes can often reduce blood pressure in many people.

Cancer

The Canadian Cancer Society reported that cancer was projected to be the main cause of death in 2017 in that country (Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee, 2018). After heart disease, cancer was the second leading cause of death for Americans in 2013 as it accounted for 22.5% of all deaths (Xu et al., 2016). According to the National Institutes of Health (2015), cancer is the name given to a collection of related diseases in which the body’s cells begin to divide without stopping and spread into surrounding tissues. These extra cells can divide and form growths called tumors, which are typically masses of tissue. Cancerous tumors are malignant, which means they can invade nearby tissues. When removed malignant tumors may grow back. Unlike malignant tumors, benign tumors do not invade nearby tissues. Benign tumors can sometimes be quite large, and when removed usually do not grow back. Although benign tumors in the body are not cancerous, benign brain tumors can be life threatening.

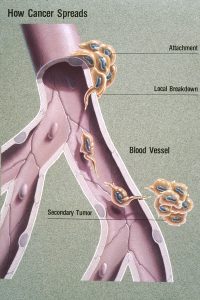

Cancer cells can prompt nearby normal cells to form blood vessels that supply the tumors with oxygen and nutrients, which allows them to grow. These blood vessels also remove waste products from the tumors. Cancer cells can also hide from the immune system, a network of organs, tissues, and specialized cells that protects the body from infections and other conditions. Lastly, cancer cells can metastasize, which means they can break from where they first formed, called the primary cancer, and travel through the lymph system or blood to form new tumors in other parts of the body. This new metastatic tumor is the same type as the primary tumor (National Institutes of Health, 2015). Figure 8.6 illustrates how cancers can metastasize.

Cancer can start almost anywhere in the human body. While normal cells mature into very distinct cell types with specific functions, cancer cells do not and continue to divide without stopping. Further, cancer cells are able to ignore the signals that normally tell cells to stop dividing or to begin a process known as programmed cell death which the body uses to get rid of unneeded cells. With the growth of cancer cells, normal cells are crowded out and the body is unable to work the way it is supposed to. For example, the cancer cells in lung cancer form tumors which interfere with the functioning of the lungs and how oxygen is transported to the rest of the body.

There are more than 100 types of cancer. The American Cancer Society assemblies a list of the most common types of cancers in the United States. To qualify for the 2016 list, the estimated annual incidence had to be 40,000 cases or more. The most common type of cancer on the list is breast cancer, with more than 249,000 new cases expected in 2016. The next most common cancers are lung cancer and prostate cancer. Table 5.29.1 lists the estimated number of new cases and deaths for each common cancer type (American Cancer Society, 2016).

| U.S.A. | Canada | |

| Breast | 124.7 | 69.2 |

| Prostate | 109.2 | 59.9 |

| Lung & Bronchus | 60.5 | 63.5 |

| Colorectum | 39.3 | 57.9 |

| Uterine Corpus | 26.2 | 18.4 |

| Melanoma | 21.2 | 21.5 |

| Urinary Bladder | 20.3 | 26.9 |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 18.9 | 26.0 |

| Kidney and Renal Pelvis | 16.4 | 16.6 |

| Thyroid | 14.4 | 15.9 |

| Leukemia | 13.8 | 15.6 |

| Pancreas | 12.7 | 12.5 |

| Oral Cavity & Pharynx | 11.6 | 13.0 |

| Ovary | 11.4 | 7.0 |

| Cervix | 7.6 | 4.1 |

| Stomach | 6.6 | 9.6 |

| Brain & Nervous System | 6.5 | 6.9 |

| Testis | 5.5 | 3.1 |

Cholesterol

Cholesterol is a waxy fatty substance carried by lipoprotein molecules in the blood. It is created by the body to create hormones and digest fatty foods, and is also found in many foods. Your body needs cholesterol, but too much can cause heart disease and stroke. Two important kinds of cholesterol are low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL). A third type of fat is called triglycerides. Your total cholesterol score is based on all three types of lipids (see Table 5.29.2). Total cholesterol is calculated by adding HDL plus LDL plus 20% of the Triglycerides.

| Normal Level | |

| Total Cholesterol | Less than 200 mg/dL* |

| LDL | Less than 100 mg/dL |

| HDL | 40 mg/dL or higher |

| Triglycerides | Less than 150 mg/dL |

| *Cholesterol levels are measured in milligrams (mg) of cholesterol per deciliter (dL) of blood | |

LDL cholesterol makes up the majority of the body’s cholesterol, however, it is often referred to as “bad” cholesterol because at high levels it can form plaque in the arteries leading to heart attack and stroke. HDL cholesterol, often referred to as “good” cholesterol, absorbs cholesterol and carries it back to the liver, where it is then flushed from the body. Higher levels of HDL can reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke. Triglycerides are a type of fat in the blood used for energy. High levels of triglycerides can also increase your risk for heart disease and stroke when coupled with high LDL and low HDL. All adults 20 or older should have their cholesterol checked. In early adulthood, doctors may check every few years if the numbers have previously been normal, and there are no other signs of heart disease. In middle adulthood, this may become part of the annual check-up (CDC, 2015).

Risk factors for high cholesterol include: A family history for high cholesterol, diabetes, a diet high in saturated fats, trans fat, and cholesterol, physical inactivity, and obesity. Almost 32% of American adults have high LDL cholesterol levels, and the majority do not have it under control, nor have they made lifestyle changes (CDC, 2015).

Diabetes

Diabetes (Diabetes Mellitus) is a disease in which the body does not control the amount of glucose in the blood. This disease occurs when the body does not make enough insulin or does not use it the way it should (NIH, 2016a). Insulin is a type of hormone that helps glucose in the blood enter cells to give them energy. In adults, 90% to 95% of all diagnosed cases of diabetes are type 2 (American Diabetes Association (ADA), 2016). Type 2 diabetes usually begins with insulin resistance, a disorder in which the cells in the muscles, liver, and fat tissue do not use insulin properly (CDC, 2014d). As the need for insulin increases, cells in the pancreas gradually lose the ability to produce enough insulin. In some Type 2 diabetics, pancreatic beta cells will cease functioning, and the need for insulin injections will become necessary. Some people with diabetes experience insulin resistance with only minor dysfunction of the beta cell secretion of insulin. Other diabetics experience only slight insulin resistance, with the primary cause being a lack of insulin secretion (CDC, 2014d).

One in three adults are estimated to have prediabetes, and 9 in 10 of them do not know. According to the CDC (2014d) without intervention, 15% to 30% of those with prediabetes will develop diabetes within 5 years. In 2012, 29 million people (over 9% of the population) were living with diabetes in America, mostly adults age 20 and up. Table 5.29.3 shows the numbers in percentage of adults, by age and gender, living with diabetes. The median age of diagnosis is 54 (CDC, 2014d). During middle adulthood, the number of people with diabetes dramatically increases; with 4.3 million living with diabetes prior to age 45, to over 13 million between the ages of 45 to 64; a four-fold increase. Men are slightly more likely to experience diabetes than are women.

| Percent in U.S.A., 2015 | Percent in Canada, 2018 | ||

| 18-44 | 3.1 | 18-34 | 0.9 |

| 45-64 | 10.9 | 35-49 | 3.9 |

| 65 and over | 9.4 | 50-64 | 10.3 |

| 65 and over | 17.9 | ||

| Women | 6.8 | Women | 6.2 |

| Men | 6.7 | Men | 8.1 |

Diabetes also affects ethnic and racial groups differently. Non-Hispanic Whites (7.6%) are less likely to be diagnosed with diabetes than are Asian Americans (9%), Hispanics (12.8%), non- Hispanic Blacks (13.2%), and American Indians/Alaskan Natives (15.9%). However, these general figures hide the variations within these groups. For instance the rate of diabetes was less for Central, South, and Cuban Americans than for Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans, and four times less for Alaskan Natives than the American Indians of southern Arizona (CDC, 2014d). Among Canadians, those with European ancestors have lower risks of diabetes than those with South Asian, Hispanic American, Chinese, or African ancestors. Additionally people from these ethnic groups develop diabetes at younger ages and with lower BMIs than Canadians with European ethnic backgrounds (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2011). Both genetic and behavioral differences underlie these ethnic disparities. Rates of diabetes in Canada vary among peoples broadly classified as First Nations. First Nations peoples living on reserve have the most elevated rates compared to the general Canadian population, while the rate of diabetes in Inuits is the same as the general population.

The risk factors for diabetes include:

- Those over age 45

- Obesity

- Family history of diabetes

- History of gestational diabetes (see Chapter 2)

- Race and ethnicity

- Physical inactivity

- Diet.

Diabetes has been linked to numerous health complications. Adults with diabetes are 1.7 times more likely to have cardiovascular disease, 1.8 times more likely to experience a heart attack, and 1.5 times more likely to experience stroke than adults without diabetes. Diabetes can cause blindness and other eye problems. In diabetics age 40 or older, 28.5% showed signs of diabetic retinopathy, damage to the small blood vessels in the retina that may lead to loss of vision. More than 4% showed advanced diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes is linked as the primary cause of almost half (44%) of new cases of kidney failure each year. About 60% of non-traumatic limb amputations occur in people with diabetes. Diabetes has been linked to hearing loss, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), gum disease, and neuropathy (nerve disease) (CDC, 2014d).

Typical tests for diabetes include a fasting glucose test and the A1C (See Table 5.29.4). Fasting glucose levels should be under 100mg/dl (ADA, 2016). The A1C provides information about the average levels of blood glucose over the last 3 months (NIH, 2014a). The A1C should be under 5.7, where a 5.0 = 97mg/dl and a 6.0 = 126 mg/dl (ADA, 2016).

| Normal | Prediabetes | Diabetes | |

| Fasting Glucose | Below 100 mg/dL | 100-125 mg/dL | 126 mg/dL + |

| A1C | Under 5.7 | 5.7-6.9 | 7 + |

| Adapted from the American Diabetes Association (2016) | |||

Metabolic Syndrome is a cluster of several cardiometabolic risk factors, including large waist circumference, high blood pressure, and elevated triglycerides, LDL, and blood glucose levels, which can lead to diabetes and heart disease (Crist et al., 2012). The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the U.S. is approximately 34% and is especially high among Hispanics and African Americans (Ford, Li, & Zhao, 2010). Prevalence increases with age, peaking in one’s 60s (Ford et al., 2010). Metabolic syndrome increases morbidity from cardiovascular disease and diabetes (Hu et al., 2004; Malik, 2004). Hu and colleagues found that even having one or two of the risk factors for metabolic syndrome increased the risk of mortality. Crist et al. (2012) found that increasing aerobic activity and reducing weight led to a drop in many of the risk factors of metabolic syndrome, including a reduction in waist circumference and blood pressure, and an increase in HDL cholesterol.

Arthritis

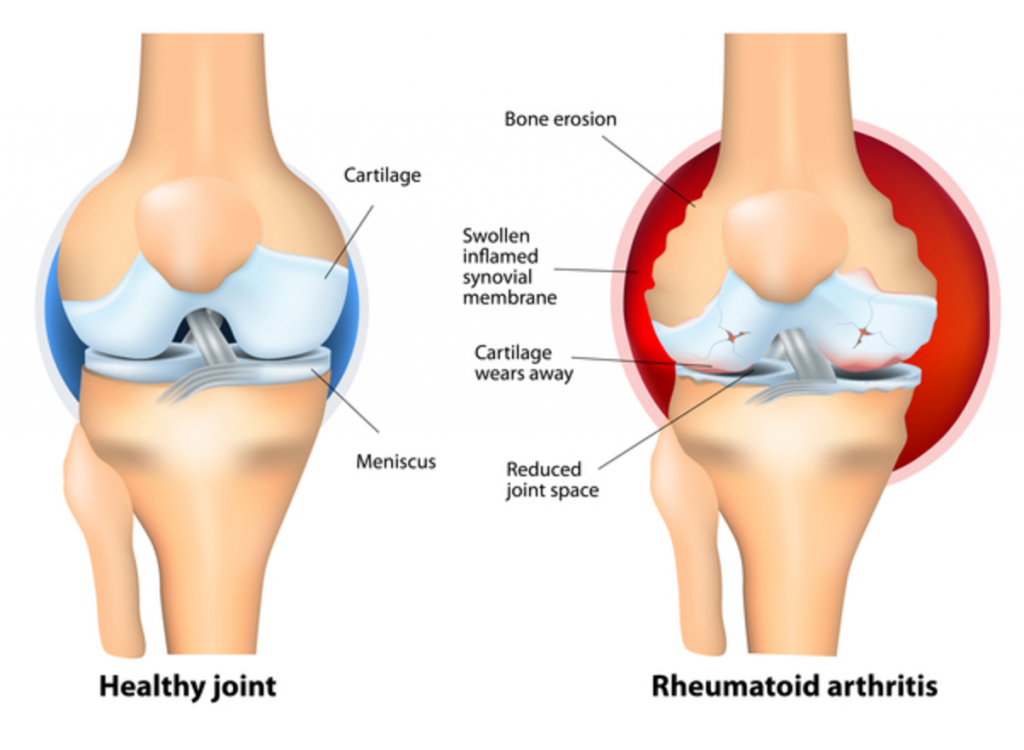

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an inflammatory disease that causes pain, swelling, stiffness, and loss of function in the joints (NIH, 2016b). RA occurs when the immune system attacks the membrane lining the joints (see Image 5.29.3). RA is the second most common form of arthritis after osteoarthritis, which is normal wear and tear on the joints. Unlike osteoarthritis, RA is symmetric in its attack of the body, thus, if one shoulder is affected so is the other. In addition, those with RA may experience fatigue and fever. Below are the common features of RA (NIH, 2016b).

Features of Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Tender, warm, swollen joints

- Symmetrical pattern of affected joints

- Joint inflammation often affecting the wrist and finger joints closest to the hand

- Joint inflammation sometimes affecting other joints, including the neck, shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, ankles, and feet

- Fatigue, occasional fevers, a loss of energy

- Pain and stiffness lasting for more than 30 minutes in the morning or after a long rest

- Symptoms that last for many years

- Variability of symptoms among people with the disease.

About 1.5 million people (approximately 0.6%) of Americans experience rheumatoid arthritis. It occurs across all races and age groups, although the disease often begins in middle adulthood and occurs with increased frequency in older people. Like some other forms of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis occurs much more frequently in women than in men. About two to three times as many women as men have the disease (NIH, 2016b). The lifetime risk for RA for women is 3.6% and 1.7% for men (Crowson, et al., 2011).

Genes play a role in the development of RA. However, individual genes by themselves confer only a small risk of developing the disease, as some people who have these particular genes never develop RA. Scientists think that something must occur to trigger the disease process in people whose genetic makeup makes them susceptible to rheumatoid arthritis. For instance, some scientists also think hormonal factors may be involved. In women who experience RA, the symptoms may improve during pregnancy and flare after pregnancy. Women who use oral contraceptives may increase their likelihood of developing RA. This suggests hormones, or possibly deficiencies or changes in certain hormones, may increase the risk of developing RA in a genetically susceptible person (NIH, 2016b).

Rheumatoid arthritis can affect virtually every area of a person’s life, and it can interfere with the joys and responsibilities of work and family life. Fortunately, current treatment strategies allow most people with RA to lead active and productive lives. Pain-relieving drugs and medications can slow joint damage, and establishing a balance between rest and exercise can also lessen the symptoms of RA (NIH, 2016b).

Digestive Issues

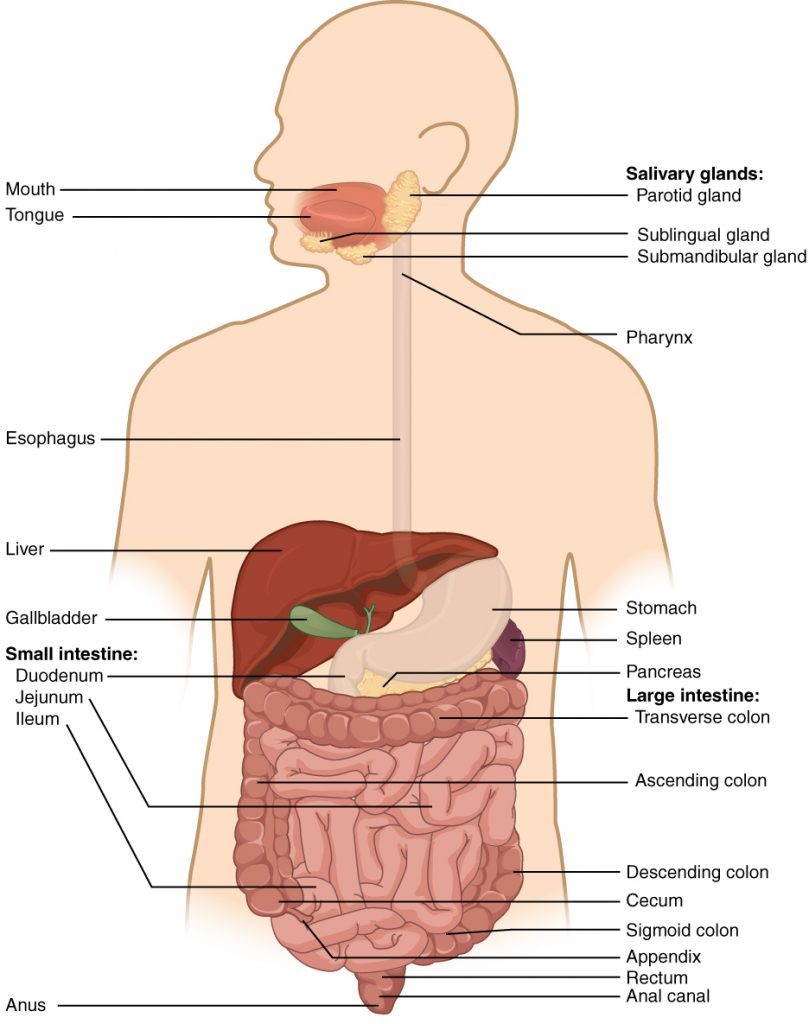

Heartburn, also called acid indigestion or pyrosis, is a common digestive problem in adults and is the result of stomach acid backing up into the esophagus. Prolonged contact with the digestive juices injures the lining of the esophagus and causes discomfort. Heartburn that occurs more frequently may be due to gastroesophageal reflux disease, GERD. Normally the lower sphincter muscle in the esophagus keeps the acid in the stomach from entering the esophagus. In GERD this muscle relaxes too frequently and the stomach acid flows into the esophagus. In the U.S. 60 million people experience heartburn at least once a month, and 15 million experience it every day. Prolonged problems with heartburn can lead to more serious complications, including esophageal cancer, one of the most lethal forms of cancer in the U.S. Problems with heartburn can be linked to eating fatty or spicy foods, caffeine, smoking, and eating before bedtime (American College of Gastroenterology, 2016a).

Gallstones are hard particles, including fatty materials, bile pigments, and calcium deposits, that can develop in the gallbladder. Ranging in size from a grain of sand to a golf ball, they typically take years to develop, but in some people have developed over the course of a few months. About 75% of gallstones do not create any symptoms, but those that do may cause sporadic upper abdominal pain when stones block bile or pancreatic ducts. If stones become lodged in the ducts, it may necessitate surgery or other medical intervention as it could become life-threatening if left untreated (American College of Gastroenterology, 2016b).

Gallstones are present in about 20% of women and 10% of men over the age of 55 (American College of Gastroenterology, 2016b). Risk factors include a family history of gallstones, diets high in calories and refined carbohydrates (such as, white bread and rice), diabetes, metabolic syndrome, Crohn’s disease, and obesity, which increases the cholesterol in the bile and thus increases the risk of developing gallstones (NIH, 2013).

Sleep

According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (Kasper, 2015) adults require at least 7 hours of sleep per night to avoid the health risks associated with chronic sleep deprivation. Less than 6 hours and more than 10 hours is also not recommended for those in middle adulthood (National Sleep Foundation, 2015). Not surprisingly, many Americans do not receive the 7-9 hours of sleep recommended. In 2013, only 59% of U.S. adults met that standard, while in 1942, 84% did (Jones, 2013). This means 41% of Americans receive less than the recommended amount of nightly sleep. Additional results included that in 1993, 67% of Americans felt they were getting enough sleep, but in 2013 only 56% felt they received as much sleep as needed. Additionally, 43% of Americans in 2013 believed they would feel better with more sleep.

Sleep problems: According to the Sleep in America poll (National Sleep Foundation, 2015), 9% of Americans report being diagnosed with a sleep disorder, and of those 71% have sleep apnea and 24% suffer from insomnia. Pain is also a contributing factor in the difference between the amount of sleep Americans say they need and the amount they are getting. An average of 42 minutes of sleep debt occur for those with chronic pain, and 14 minutes for those who have suffered from acute pain in the past week. Stress and overall poor health are also key components of shorter sleep durations and worse sleep quality. Those in midlife with lower life satisfaction experienced greater delay in the onset of sleep than those with higher life satisfaction. Delayed onset of sleep could be the result of worry and anxiety during midlife, and improvements in those areas should improve sleep. Lastly, menopause can affect a woman’s sleep duration and quality (National Sleep Foundation, 2016).

Children in the home and sleep: As expected, having children at home affects the amount of sleep one receives. According to a 2016 National Center for Health Statistics analysis (CDC, 2016) having children decreases the amount of sleep an individual receives, however, having a partner can improve the amount of sleep for both males and females. Table 5.29.5 illustrates the percentage of individuals not receiving seven hours of sleep per night based on parental role.

| Demographic | Mothers/Women | Fathers/Men |

| Single Parent | 43.5% | 37.5% |

| Parent with Partner | 31.2% | 34.1% |

| without Children | 29.7% | 32.3% |

| Adapted from the the CDC, 2016 | ||

Negative consequences of insufficient sleep: There are many consequences of too little sleep, and they include physical, cognitive, and emotional changes. Sleep deprivation suppresses immune responses that fight off infection, and can lead to obesity, memory impairment, and hypertension (Ferrie et al., 2007; Kushida, 2005). Insufficient sleep is linked to an increased risk for colon cancer, breast cancer, heart disease and type 2 diabetes (Pattison, 2015). A lack of sleep can increase stress as cortisol (a stress hormone) remains elevated which keeps the body in a state of alertness and hyperarousal which increases blood pressure.

Sleep is also associated with longevity. Dew et al. (2003) found that older adults who had better sleep patterns also lived longer. During deep sleep a growth hormone is released which stimulates protein synthesis, breaks down fat that supplies energy, and stimulates cell division. Consequently, a decrease in deep sleep contributes to less growth hormone being released and subsequent physical decline seen in aging (Pattison, 2015).

Sleep disturbances can also impair glucose functioning in middle adulthood. Caucasian, African American, and Chinese non-shift-working women aged 48–58 years who were not taking insulin-related medications, participated in the Study of Women’s Health across the Nation (SWAN) Sleep Study and were subsequently examined approximately 5 years later (Taylor et al., 2016). Body mass index (BMI) and insulin resistance were measured at two time points. Results indicated that irregular sleep schedules, including highly variable bedtimes and staying up much later than usual, are associated in midlife women with insulin resistance, which is an important indicator of metabolic health, including diabetes risk. Diabetes risk increases in midlife women, and irregular sleep schedules may be an important reason because irregular bedtime schedules expose the body to varying levels of light, which is the most important timing cue for the body’s circadian clock. By disrupting circadian timing, bedtime variability may impair glucose metabolism and energy homeostasis.

Exercise, Nutrition, and Weight

The impact of exercise

Exercise is a powerful way to combat the changes we associate with aging. Exercise builds muscle, increases metabolism, helps control blood sugar, increases bone density, and relieves stress. Unfortunately, fewer than half of midlife adults exercise and only about 20 percent exercise frequently and strenuously enough to achieve health benefits. Many stop exercising soon after they begin an exercise program, particularly those who are very overweight. The best exercise programs are those that are engaged in regularly, regardless of the activity. A well-rounded program that is easy to follow includes walking and weight training. Having a safe, enjoyable place to walk can make the difference in whether or not someone walks regularly. Weight lifting and stretching exercises at home can also be part of an effective program. Exercise is particularly helpful in reducing stress in midlife. Walking, jogging, cycling, or swimming can release the tension caused by stressors. Learning relaxation techniques can also have healthful benefits. Exercise can be thought of as preventative health care. Promoting exercise for the 78 million “baby boomers” may be one of the best ways to reduce health care costs and improve quality of life (Shure & Cahan, 1998).

According to the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2008), the following are exercise guidelines for adults:

- Adults should avoid being inactive. Any activity will result in some health benefits.

- For substantial health benefits, adults should engage in at least 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity exercise OR at least 75 minutes of vigorous intensity aerobic activity. Aerobic activity should occur for at least 10 minutes and preferably spread throughout the week.

- For more extensive health benefits, adults can increase their aerobic activity to 300 minutes per week of moderate intensity OR 150 minutes per week of vigorous intensity aerobic activity.

- Adults should also participate in muscle-strengthening activities that are moderate or high intensity and involve all major muscle groups on two or more days per week.

Nutritional concerns

Aging brings about a reduction in the number of calories a person requires (see Table 5.29.6 for estimated caloric needs in middle-aged adults). Many Americans respond to weight gain by dieting. However, eating less does not typically mean eating right and people often suffer vitamin and mineral deficiencies as a result. All adults need to be especially cognizant of the amount of sodium, sugar, and fat they are ingesting.

|

Males |

Females |

|||||

| Age | Sedentary | Moderately Active | Active | Sedentary | Moderately Active | Active |

| 36-40 | 2400 | 2600 | 2800 | 1800 | 2000 | 2200 |

| 41-45 | 2200 | 2600 | 2800 | 1800 | 2000 | 2200 |

| 46-50 | 2200 | 2400 | 2800 | 1800 | 2000 | 2200 |

| 51-55 | 2200 | 2400 | 2800 | 1600 | 1800 | 2200 |

| 56-60 | 2200 | 2400 | 2600 | 1600 | 1800 | 2200 |

| 61-65 | 2000 | 2400 | 2600 | 1600 | 1800 | 2000 |

| Adapted from 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans | ||||||

Excess Sodium: According to dietary guidelines, adults should consume less than 2,300mg (1 teaspoon) per day of sodium. The American Heart Association (2016) reports that the average sodium intake among Americans is 3440mg per day. Processed foods are the main culprits of excess sodium. High sodium levels in the diet is correlated with increased blood pressure, and its reduction does show corresponding drops in blood pressure. Adults with high blood pressure are strongly encouraged to reduce their sodium intake to 1500mg (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Agriculture (USHHS & USDA), 2015).

Excess Fat: Dietary guidelines also suggests that adults should consume less than 10 percent of calories per day from saturated fats. The American Heart Association (2016) says optimally we should aim for a dietary pattern that achieves 5% to 6% of calories from saturated fat. In a 2000 calorie diet that is about 120 calories from saturated fat. In the average American diet about 34.3% of the diet comes from fat, with 15.0% from saturated fat (Berglund et al., 1999). Diets high in fat not only contribute to weight gain, but have been linked to heart disease, stroke, and high cholesterol.

Added Sugar: According to the recent Dietary Guidelines for Americans (USHHS & USDA, 2015) eating healthy means adults should consume less than 10 percent of calories per day from added sugars. Yet, currently about 15% of the calories in the American adult diet come from added sugars, or about 22 teaspoons of sugar per day (NIH, 2014c). Excess sugar not only contributes to weight gain, but diabetes and other health problems.

Metabolism and Weight Gain

One of the common complaints of midlife adults is weight gain, especially the accumulation of fat in the abdomen, which is often referred to as the middle-aged spread (Lachman, 2004). Men tend to gain fat on their upper abdomen and back, while women tend to gain more fat on their waist and upper arms. Many adults are surprised at this weight gain because their diets have not changed, however, their metabolism has slowed during midlife. Metabolism is the process by which the body converts food and drink into energy. The calories consumed are combined with oxygen to release the energy needed to function (Mayo Clinic, 2014b). People who have more muscle burn more calories, even at rest, and thus have a higher metabolism.

However, as you get older, the amount of muscle decreases. Consequently, fat accounts for more of one’s weight in midlife and slows down the amount of calories burned. To compensate, midlife adults have to increase their level of exercise, eat less, and watch their nutrition to maintain their earlier physique.

Obesity: As discussed in the early adulthood chapter, obesity is a significant health concern for adults throughout the world, and especially America. Obesity rates continue to increase, and being overweight is associated with a myriad of health conditions including diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease. New research is now linking obesity to Alzheimer’s disease. Chang et al. (2016) found that being overweight in midlife was associated with earlier onset of Alzheimer’s disease. The study looked at 1,394 men and women who were part of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Their average age was around 60, and they were followed for 14 years. Results indicated that people with the highest body mass index, or BMI, at age 50 were more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease. In fact, each one-point increase in BMI was associated with getting Alzheimer’s six to seven months earlier. Those with the highest BMIs also had more brain changes typical of Alzheimer’s, even if they did not have symptoms of the disease. Scientists speculate that fat cells may produce harmful chemicals that promote inflammation in blood vessels throughout the body, including in the brain. The conclusion of the study was that a healthy BMI at midlife may delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Concluding Thoughts

Many of the changes that occur in midlife can be easily compensated for, such as buying glasses, exercising, and watching what one eats. However, the percentage of middle adults who have a significant health concern has increased in the past 15 years.

According to the 2016 United Health Foundation’s America’s Health Rankings Senior Report, the next generation of seniors will be less healthy than the current seniors (United Health Foundation, 2016). The study compared the health of middle-aged Americans (50-64 years of age) in 2014 to middle-aged Americans in 1999. Results indicated that in the past 15 years the prevalence of diabetes has increased by 55% and the prevalence of obesity has increased by 25%. At the state level, Massachusetts ranked first for healthy seniors, while Louisiana ranked last. Illinois ranked 36th, while Wisconsin scored higher at 13th.

What can we conclude from this information? Lifestyle has a strong impact on the health status of midlife adults, and it becomes important for midlife adults to take preventative measures to enhance physical well-being. Those midlife adults who have a strong sense of mastery and control over their lives, who engage in challenging physical and mental activity, who engage in weight bearing exercise, monitor their nutrition, receive adequate sleep, and make use of social resources are most likely to enjoy a plateau of good health through these years (Lachman, 2004).

Media Attributions

- 063-Artherosclerosis © NIH: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Metastasis_illustration

- 065-RheumatoidArthritis © National Library of Medicine, US is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 066-DIgestiveSystem © OpenStax College is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license