31 Cognitive Development in Middle Adulthood

Brain Functioning

The brain at midlife has been shown to not only maintain many of the abilities of young adults, but also gain new ones. Some individuals in middle age actually have improved cognitive functioning in some areas (Phillips, 2011). The brain continues to demonstrate plasticity and rewires itself in middle age based on experiences. Research has demonstrated that healthy middle-aged and older adults sometimes use more of their brains than younger adults in performing the same mental task. This is usually interpreted as the brain making up for negative changes in brain functioning with age by using more of the brain. Some studies show that older adults who perform the best on tasks are more likely to demonstrate bilateralization than those who perform worst. Additionally, the amount of white matter in the brain, which is responsible for forming connections among neurons, increases into the 50s in some people before it declines. Maintaining and building on physical and mental health promotes this positive trajectory.

Emotionally, the middle aged brain is calmer, less neurotic, more capable of managing emotions, and better able to negotiate social situations (Phillips, 2011). Older adults tend to focus more on positive information and less on negative information than those younger. In fact, they also remember positive images better than those younger. Additionally, the older adult’s amygdala responds less to negative stimuli. Lastly, in general adults in middle adulthood make better financial decisions than they did when younger. As knowledge banks (crystallized intelligence) increase, we show better economic understanding as we transition from being younger to being between younger and older adulthood.

Physical activity, mental challenge, and social engagement promote the ongoing dynamism of development and increase the likelihood that a person in middle age will show improvements in some areas of thinking. Communities and societies can do a lot to support and foster this growth. Intergenerational teams, classes, organizations, and communities can synergize societal growth and support the development of each cohort.

Crystalized versus Fluid Intelligence

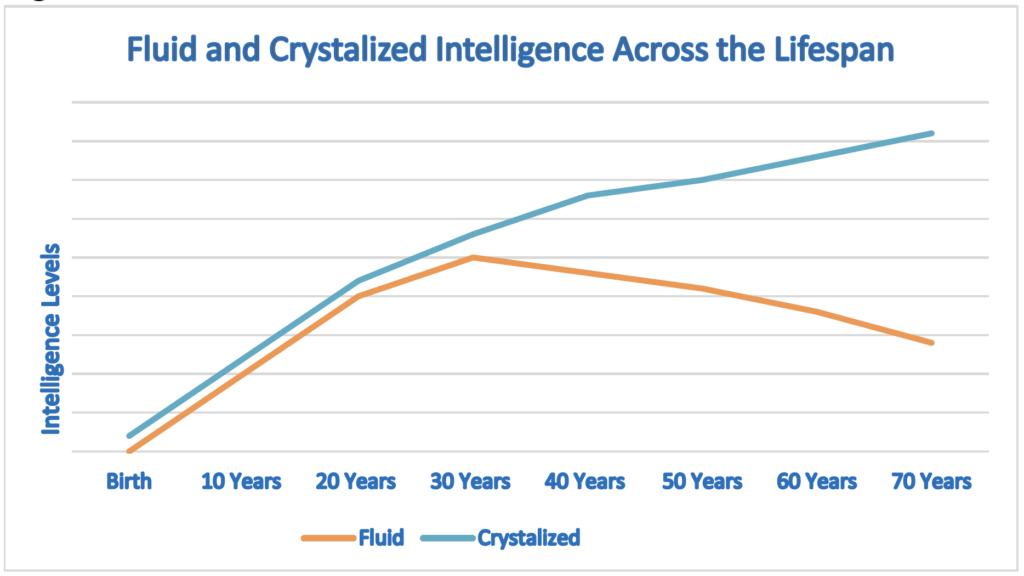

Intelligence is influenced by heredity, culture, social contexts, personal choices, and certainly age. One distinction in specific intelligences noted in adulthood, is between fluid intelligence, which refers to the capacity to learn new ways of solving problems and performing activities quickly and abstractly, and crystallized intelligence, which refers to the accumulated knowledge of the world we have acquired throughout our lives (Salthouse, 2004). These intelligences are distinct, and crystallized intelligence increases with age, while fluid intelligence tends to decrease with age (Horn, Donaldson, & Engstrom, 1981; Salthouse, 2004).

Research demonstrates that older adults have more crystallized intelligence as reflected in semantic knowledge, vocabulary, and language. As a result, adults generally outperform younger people on measures of history, geography, and even on crossword puzzles, where this information is useful (Salthouse, 2004). It is this superior knowledge, combined with a slower and more complete processing style, along with a more sophisticated understanding of the workings of the world around them, that gives older adults the advantage of “wisdom” over the advantages of fluid intelligence which favor the young (Baltes, Staudinger, & Lindenberger, 1999; Scheibe, Kunzmann, & Baltes, 2009).

The differential changes in crystallized versus fluid intelligence help explain why older adults do not necessarily show poorer performance on tasks that also require experience (i.e., crystallized intelligence), although they show poorer memory overall. A young chess player may think more quickly, for instance, but a more experienced chess player has more knowledge to draw on.

Seattle Longitudinal Study

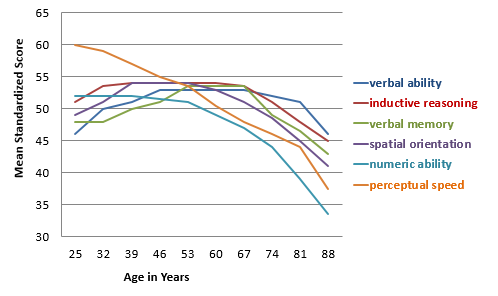

The Seattle Longitudinal Study has tracked the cognitive abilities of adults since 1956. Every seven years the current participants are evaluated and new individuals are also added. Approximately 6000 people have participated thus far, and 26 people from the original group are still in the study today. Current results demonstrate that middle-aged adults perform better on four out of six cognitive tasks than those same individuals did when they were young adults. Verbal memory, spatial skills, inductive reasoning (generalizing from particular examples), and vocabulary increase with age until one’s 70s (Schaie, 2005; Willis & Shaie, 1999). However, numerical computation and perceptual speed decline in middle and late adulthood (see Image 5.31.2).

Cognitive skills in the aging brain have been studied extensively in pilots, and similar to the Seattle Longitudinal Study results, older pilots show declines in processing speed and memory capacity, but their overall performance seems to remain intact. According to Phillips (2011) researchers tested pilots age 40 to 69 as they performed on flight simulators. Older pilots took longer to learn to use the simulators, but performed better than younger pilots at avoiding collisions.

Flow is the mental state of being completely present and fully absorbed in a task (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). When in a state of flow, the individual is able to block outside distractions and the mind is fully open to producing. Additionally, the person is achieving great joy or intellectual satisfaction from the activity and accomplishing a goal. Further, when in a state of flow, the individual is not concerned with extrinsic rewards. Csikszentmihalyi (1996) used his theory of flow to research how some people exhibit high levels of creativity as he believed that a state of flow is an important factor to creativity (Kaufman & Gregoire, 2016). Other characteristics of creative people identified by Csikszentmihalyi (1996) include curiosity and drive, a value for intellectual endeavors, and an ability to lose our sense of self and feel a part of something greater. In addition, he believed that the tortured creative person was a myth and that creative people were very happy with their lives. According to Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi (2002) people describe flow as the height of enjoyment. The more they experience it, the more they judge their lives to be gratifying. The qualities that allow for flow are well-developed in middle adulthood.

Tacit knowledge is knowledge that is pragmatic or practical and learned through experience rather than explicitly taught, and it also increases with age (Hedlund, Antonakis, & Sternberg, 2002). Tacit knowledge might be thought of as “know-how” or “professional instinct.” It is referred to as tacit because it cannot be codified or written down. It does not involve academic knowledge, rather it involves being able to use skills and to problem-solve in practical ways. Tacit knowledge can be understood in the workplace and used by blue collar workers, such as carpenters, chefs, and hair dressers.

MIDDLE ADULTS RETURNING TO EDUCATION

Midlife adults in the United States often find themselves in college classrooms. In fact, the rate of enrollment for older Americans entering college, often part-time or in the evenings, is rising faster than traditionally aged students. Students over age 35, accounted for 17% of all college and graduate students in 2009, and are expected to comprise 19% of that total by 2020 (Holland, 2014). Up to at least 2010 in Canada enrolment growth was faster in students of traditional university/college age , although the number of older university and college students also was rising (Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada, 2011).

In some cases, older students are developing skills and expertise in order to launch a second career, or to take their career in a new direction. Whether they enroll in school to sharpen particular skills, to retool and reenter the workplace, or to pursue interests that have previously been neglected, older students tend to approach the learning process differently than younger college students (Knowles, Holton, & Swanson, 1998).

The mechanics of cognition, such as working memory and speed of processing, gradually decline with age. However, they can be easily compensated for through the use of higher order cognitive skills, such as forming strategies to enhance memory or summarizing and comparing ideas rather than relying on rote memorization (Lachman, 2004). Although older students may take a bit longer to learn material, they are less likely to forget it quickly. Adult learners tend to look for relevance and meaning when learning information. Older adults have the hardest time learning material that is meaningless or unfamiliar. They are more likely to ask themselves, “Why is this important?” when being introduced to information or when trying to memorize concepts or facts. Older adults are more task-oriented learners and want to organize their activity around problem-solving. However, these differences may decline as new generations, equipped with higher levels of education, begin to enter midlife.

To address the educational needs of those over 50, The American Association of Community Colleges (2016) developed the Plus 50 Initiative that assists community college in creating or expanding programs that focus on workforce training and new careers for the plus-50 population. Since 2008 the program has provided grants for programs to 138 community colleges affecting over 37, 000 students. The participating colleges offer workforce training programs that prepare 50 plus adults for careers in such fields as early childhood educators, certified nursing assistants, substance abuse counselors, adult basic education instructors, and human resources specialists. These training programs are especially beneficial as 80% of people over the age of 50 say they will retire later in life than their parents or continue to work in retirement, including in a new field.

Gaining Expertise: The Novice and the Expert

Expertise refers to specialized skills and knowledge that pertain to a particular topic or activity. In contrast, a novice is someone who has limited experiences with a particular task. Everyone develops some level of “selective” expertise in things that are personally meaningful to them, such as making bread, quilting, computer programming, or diagnosing illness. Expert thought is often characterized as intuitive, automatic, strategic, and flexible.

- Intuitive: Novices follow particular steps and rules when problem solving, whereas experts can call upon a vast amount of knowledge and past experience. As a result, their actions appear more intuitive than formulaic. A novice cook may slavishly follow the recipe step by step, while a chef may glance at recipes for ideas and then follow her own procedure.

- Automatic: Complex thoughts and actions become more routine for experts. Their reactions appear instinctive over time, and this is because expertise allows us to process information faster and more effectively (Crawford & Channon, 2002).

- Strategic: Experts have more effective strategies than non-experts. For instance, while both skilled and novice doctors generate several hypotheses within minutes of an encounter with a patient, the more skilled clinicians’ conclusions are likely to be more accurate. In other words, they generate better hypotheses than the novice. This is because they are able to discount misleading symptoms and other distractors and hone in on the most likely problem the patient is experiencing (Norman, 2005). Consider how your note taking skills may have changed after being in school over a number of years. Chances are you do not write down everything the instructor says, but the more central ideas. You may have even come up with your own short forms for commonly mentioned words in a course, allowing you to take down notes faster and more efficiently than someone who may be a novice academic note taker.

- Flexible: Experts in all fields are more curious and creative; they enjoy a challenge and experiment with new ideas or procedures. The only way for experts to grow in their knowledge is to take on more challenging, rather than routine tasks.

Expertise takes time. It is a long-process resulting from experience and practice (Ericsson, Feltovich, & Prietula, 2006). Middle-aged adults, with their store of knowledge and experience, are likely to find that when faced with a problem they have likely faced something similar before. This allows them to ignore the irrelevant and focus on the important aspects of the issue. Expertise is one reason why many people often reach the top of their career in middle adulthood.

However, expertise cannot fully make-up for all losses in general cognitive functioning as we age. The superior performance of older adults in comparison to younger novices appears to be task specific (Charness & Krampe, 2006). As we age, we also need to be more deliberate in our practice of skills in order to maintain them. Charness and Krampe (2006) in their review of the literature on aging and expertise, also note that the rate of return for our effort diminishes as we age. In other words, increasing practice does not recoup the same advances in older adults as similar efforts do at younger ages.

Media Attributions

- 072-IntelligenceLifespan

- 073-SeattleLongitudinalStudy © Lally & Valentine