Introduction

Let’s get started! Introductions are important trust builders.

Henry L. Stimson

This is a book about trust. More specifically, it’s about what I call trust systems. I’ll discuss what these are in more detail through the book, but for an introduction, think of it this way: A system is things working together to do something. A trust system is no different.

A trust system is a collection of three necessary and sufficient things:

- people

- process

- place

We can look at these things in isolation and examine how they all work together to help agents in a trust relationship make decisions — where the decisions come from and how they got there. People in the trust system are the agents in an interaction. They think about, act on, and otherwise engage with trust as a phenomenon. Processes are how trust is thought about, measured, decided. Places are the environments or contexts (real or virtual or imagined) that the trust decisions are made in. Trust is highly contextual, so it’s important to think about that. For instance, I would trust my brother to drive me to the airport but not to fly the plane. The plane and the car are places in the trust system between my brother and myself where, of course, the process is flying or driving. Sometimes, process and place can be quite difficult to peel apart, but that’s okay. So much for a system. We’ll come back to it in much more detail, particularly when we talk about how[1] trust works.

Another question may have occurred to you as you read. What, exactly, is trust? That’s a more difficult question to answer than you might think. I mean, it’s pretty easy for anyone to tell you what trust means to them (some languages don’t have a separate word for trust, though). But what is it, well for all of us, specifically (or generally)?

Put simply, it’s complicated.

A basic way of looking at it, that I’ve used in a lot of my work, is wonderfully described by Piotr Cofta (Cofta, 2007): trust is a way of accepting the fact that we can’t control everything that happens around us. As Niklas Luhmann (Luhmann, 1979) would put it, it’s a way of simplifying the decisions we have to make every day, and not think about the many things that, if we did think about them, would make us not want to get out of bed in the morning. Things like crossing the road. Things like riding a bike in heavy traffic. Things that we take on trust: that people driving a big red bus won’t deliberately try to drive over us, for instance.

Trust is the foundation of a functioning society because of this (Bok, 1982). It is the acceptance of risk in a society where we can’t control everyone. It exists because risk exists and we can’t just stand still and do nothing. It’s a social construct that doesn’t even exist outside our heads but that, if it is betrayed, can hurt us. And, whilst we can’t control people, trusting them allows us to shape their behaviour in interesting ways. As a matter of fact, as I type you can see this kind of thing playing out in places where COVID vaccinations and mask mandates exist – a lack of trust in people to act in the best interests of those around them leads to societal impositions and fractures.

All very well, but why study trust?

There are a few reasons. It’s a fascinating phenomenon which, as you already heard, makes societies work. It’s a slippery phenomenon that defies singular definitions. And yet, what would we do without it? It is almost impossible to imagine an environment or society where trust isn’t, and if we can, it’s dystopian and horrific, truly a Hobbesian world where life is ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.’ Indeed there have been examples of such societies, and it’s probably possible to see them today (more’s the pity) where the lives of people are severely constrained. But we won’t get too far into that particular problem of humankind. At least, not yet.

If you’ll forgive a personal anecdote in what is a personal exploration, the time that trust became much more interesting to me was when I was doing some research for my PhD back in the ’90s. I was trying to understand how individual artificial autonomous agents[2] in a society of multiple other self-interested autonomous agents could make decisions about each other in a meaningful way. As you do when you’re starting on a Ph.D., I was reading a lot. One PhD thesis I came upon was a great one by Jeff Rosenschein. You can grab the thesis from here. In it, things like working together for agents were discussed in great detail. And on page 32 of the thesis there was this line:

“It is essential for our analysis that the agents are known to be trustworthy; the model would have to be developed further to deal with shades of trustworthy behaviour on the part of agents.”

I think I sat there for some time looking at that sentence and wondering to myself exactly what was meant by trustworthy and by extension (it seemed to me at the time) trust. And that’s how it all began.

You see, it’s all very well to insist that trust has to exist in such situations or societies (because we made them and they are made of us). That kind of misses the point though, because when we let these ‘agents’ go to do their work we are no longer in a state of control. This includes self-driving cars, an AI that tweets, algorithms that trade in stocks, an AI that monitors students as they do their exams online, an AI that predicts recidivism, and much more. Whilst trust has been a human province for as long as there have been humans, we’re now in a situation where we really can’t afford to ignore the artificial autonomous entities around us. Like it or not, this has something to do with trust.

In this book, I build on a foundation of the cumulative understanding of trust from many centuries of work. I take it and examine it in the light of computational systems, those autonomous agents I mentioned before. Since 1990 and that line in Rosenchein’s Ph.D. thesis, I have worked on what has come to be called computational trust[3]. Simply put, it’s the exploration of how trust might be incorporated into the decisions artificial autonomous agents make. More, it’s an aspect of how we as humans might think about these agents.

Some would say that thinking about trusting an autonomous agent or an AI is a misunderstanding for the simple reason that we can’t trust AI. Indeed, we don’t need to because we can build in things like reliability and accountability and transparency (Bryson, 2018). Accountability is a big one here, and we’ll come back to it, but really this kind of argument is all about control and controlling the computational (autonomous) systems around us. Because when we control the thing, we don’t actually need to trust it at all. Because when the thing is completely transparent to us, we don’t need to trust it. We can see it and how it works (and why).

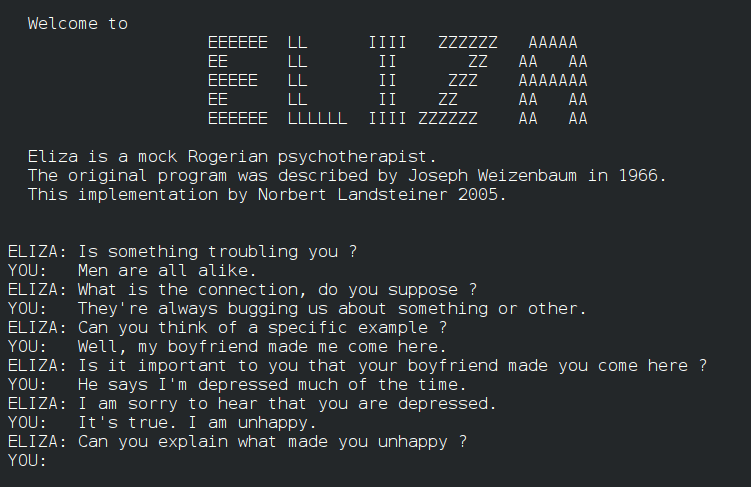

That’s possibly true if we want to see humans as rational creatures who do sensible things. They aren’t and they don’t. Human beings see technology as a social actor. As Reeves and Nass found out a long time ago – and as we will see a bit more when I start talking about Trustworthy AI – people see media and computers (and by extension artificial actors) as social actors (Reeves & Nass, 1996). Anyone who has heard of Eliza and Weizenbaum (1976) would tell you, people see artificial things differently than we would, perhaps, want them to.

This doesn’t mean that it’s correct to think this way. It doesn’t mean it’s incorrect either. it’s just a reality. And that means that we can either tell people not to do it and be ignored. Or we can help them do it better.

There’s another reality that is just as important. There is constant pressure these days to make AI more ‘trustworthy’ so that people will trust it more. This is interesting not because it is right or wrong, but because it totally misses the point: what are we trusting the AI for? What are we expecting it to do for us, and what is the context we are expecting it in. And it wouldn’t stop there in any case because as anyone who has interacted with dogs or cats or horses or many other animals before could tell you, you can both trust and be trusted by them. The real question is, “What for?”

Actually, the real question is more like this: why do you think someone would trust something or someone else just because it (or they) is trustworthy. That’s not how trust works.

To compare with humans, anyone paying attention to the world around them would hear about things like the lack of trust in politicians, or the need to think about trusting reporters more, or scientists more, and so on.. The question is the same. What for? As we will see shortly, Onora O’Neill has her own views about this.

- I see ↵

- What are these? A simple explanation is that they are bits of code that are independent from our control out there doing things 'for' us. It can get a bit more complex because, you see, robots can be seen as such agents. And then it gets even more complex because we can, hopefully, take the idea and apply it to biological organisms like animals and other people. It's all quite fun. ↵

- To toot my own horn, I created the field. ↵