15 Assessing the Affective Domain in Child and Youth Care

Paola Ostinelli

MARCH 2021

The foundation of evaluation, outcomes, and objectives in post-secondary education has traditionally been based on Bloom’s Taxonomy which outlines cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains of learning (Armstrong, n.d.; Camelia, Ferris & Cropley, 2018; Centre for Teaching Excellence, n.d.; Oughton & Pierre, 2002; Wu et al., 2019). While it can be argued that the cognitive domain is most easily evaluated, with a variety of research to support its use, there are elements of education in many professions, such as the evaluation of ethical practice, that go beyond the cognitive domain.

Specific academic programs, such as those in the helping professions, are based on a foundation of ethical practice, demonstrating relational skills, utilizing empathy, and connecting with others. Practitioners in these fields do not have external tools with which to practice; instead, they use the self as a tool. One such profession is the field of Child and Youth Care. Students are taught based on a provincial code of ethics and professional competencies which outline foundational knowledge relating to the profession. Shaw (2011) describes teaching Child and Youth Care as follows: “we support learners to understand how they will show up on the floor and in their relationships, how their values, beliefs, thoughts, ideas, and previous experiences will show up as they engage in practice” (p. 165). Evaluating a math equation or a life-saving procedure can be seemingly more tangible than evaluating one’s core beliefs!

Assessing a student’s interest or understanding of a topic in the helping professions, can be done more concretely. Currently, the evaluation in post-secondary education seems to be on focused on the cognitive domain, however values and beliefs cannot be accurately evaluated on cognition alone. With the use of activities and evaluations relevant to the affective domain, instructors can more accurately evaluate student learning on topics such as understanding the importance of ethical practice, and students experience a sense of mastering this crucial skill.

The Affective Domain

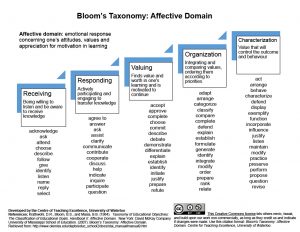

The affective domain has been described as evaluating an “emotional response concerning one’s attitudes, values and appreciation for motivation in learning” (Centre for Teaching Excellence, n.d.). This was not included in the original publication of the taxonomy; instead, it was part of an updated publication titled “The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook II: Affective Domain” (Krathwohl et al., 1964 as cited in Allen & Friedman, 2010; Lynch et al., 2009).

Allen and Freidman (2010) describe values as “a concept or an ideal that we feel strongly about, so much so that it influences the way in which we understand other ideas and interpret events.” (p. 3). With this description in mind, using the example of values or ethics when exploring the affective domain, one can gain a better understanding of how learning can be measured beyond the cognitive domain.

The following H5P activity gives an overview of the five levels that are evaluated within the affective domain, and provides a brief description for each.

This material is an adaptation of Bloom’s Taxonomy: Affective Domain. Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo and is licensed CC BY-NC 2.0

In recent years, there has been an increasing amount of research available on this domain which has focused on fields such as engineering, science, mathematics (STEM), and health professions and how the affective domain can be relevant in terms of evaluating how well students internalize information and integrate their learning into their own value system (Wu et al., 2019; Batt, 2015; Adelson & McCoach, 2011; Allen & Friedman, 2010; Boyd et al., 2006; Baker, 2004). These fields, however, do not encompass all professions. More research is needed which focuses on fields in the helping professions, such as Child and Youth Care, where values and ethics are an important component to the profession. There has been some research carried out in the field of Social Work around the use of the affective domain (Allen & Friedman, 2010) which links student learning ethics, values, and their own practice, along with affective assessment in the form of completing reflections. This can be further extended to other fields in the helping professions, such as Child and Youth Care since there are some similarities among the teaching of ethical values and professional standards.

The field of Child and Youth Care is rooted in relational practice (Garfat, Freeman, Gharabaghi & Fulcher, 2019). This is highlighted throughout the program and scaffolded into various courses. In terms of practice, Child and Youth Care Practitioners have a Code of Ethics to follow (OACYC, 2020) as well as a set of competencies which guide our practice within the “Competencies for Professional Child & Youth Work Practitioners” (Association for Child and Youth Care Practice, 2010). Ensuring students have a strong understanding of the Code of Ethics, and the expectations of what a Child and Youth Care Practitioner does when working with children, youth, and families, is important. Before a student goes out to their first field placement, it is important to instill the values and ethics of the field, and to have students make the connection to their own beliefs and values. Having knowledge of the code of ethics is one thing; being able to not only apply their learning but also integrate their learning into their very practice is of even greater importance. Evaluating the later levels of the affective domain (organizing and characterizing) give insight into deeper learning that the student has made.

When educating students, the focus has traditionally been on providing information, outlining the Code of Ethics, and incorporating activities and learning opportunities which evaluate a student’s understanding of the competencies. The practical component comes in with the use of field placement experiences, which have their own evaluation criteria. In the classroom… how might this understanding be evaluated? And how do we evaluate this before a student enters the field? By using descriptions connected to the affective domain, an instructor can scaffold and measure learning using a variety of activities and methods of evaluation geared specifically to elements such as ethical decision making. Although the affective domain has been highlighted as being difficult to evaluate (Allen & Friedman, 2010; Baker, 2004; Batt, 2015; Oughton & Pierre, 2002), there are ways to achieve this through class activities, assignments, and targeted evaluation strategies.

Activities and Evaluation

The University of Waterloo’s Centre for Teaching Excellence (n.d.) provides a list of performance verbs that can be used when designing learning outcomes, see Figure 1 below.

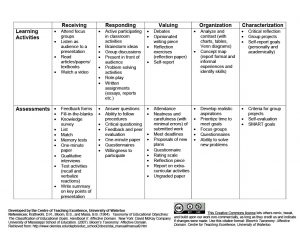

The document also outlines various learning activities and assessments for different levels within the affective domain taxonomy that can be used to evaluate learning, such as group discussions, debates, and journaling as assignments, listed in Figure 2 below.

Research supports the use of these learning opportunities (Batt, 2015; Allen & Friedman, 2010; Oughton & Pierre, 2002). Other examples include code-oriented teaching (teaching a Code of Ethics, specifically), and integrating theories and ethical principles to relevant case studies (Avci, 2017; Weston, 2011).

The affective domain is fitting when evaluating areas of learning such as empathy, ethics, among others. Allen & Friedman (2010) explored affective learning in social work practice. Research has found that reflection (Batt, 2015), connection and regular communication with instructors, and students receiving timely verbal and written feedback from their instructor (Baker, 2004) are among the most effective methods of predicting student mastery, as well as forms of evaluating elements of the affective domain. One of the most widely used methods of evaluating learning in the Child and Youth Care field has been the use of reflection. Examples of resources that utilize reflection include Budd (2020) and Burns (2016). These texts offer examples that outline the reflective process in detail, utilize reflection, and critical thinking, and provide practical applications to the field of Child and Youth Care. Both include reflection prompts, activities, self-evaluation questions and descriptions that relate to our practice working with young people and families. When faculty utilize tools such as these texts, it is important to create opportunities for students to apply their learning in the classroom and find the relevance to their work in the field. The activities described echo suggestions by Lee (2019) who outlines the benefits of teaching ethical dilemmas. “Introducing ethical dilemmas in the classroom can open up opportunities not only for debate and critical thinking, but also for personal growth, empathy for other viewpoints, and self-reflection” (Lee, 2019, p. 1). Using Child and Youth Care-specific examples and opportunities for learning ties in well with Lee’s suggestions. These are also relevant to other helping professions and can be adapted to fit individual program needs.

Creative problem solving is also important in understanding ethics (Weston, 2011); this can be done using case studies, outlining a situation a student may encounter in the field, and provide an opportunity to work with others (in groups or teams) to problem solve and gain an understanding of personal morals. This can then then be applied to the understanding of ethics, both personal as well as those outlined by the field through a Code of Ethics, such as those in Child and Youth Care practice (OACYC, 2020). Oughton and Pierre (2002) also describe the use of student journals being completed before and after a situation, which can explore a student’s change in attitude, as well as their application of learning to other courses and their work in the field.

In addition to these assignment examples, it is equally important to outline how learning is being evaluated. This can be straightforward when evaluating specific questions to a case study, or the learning gained from a debate or a group assignment, but this becomes slightly more difficult when evaluating a student’s understanding of ethics. One way to evaluate this is by using a rubric. The Association of American Colleges and Universities (2017) has developed a rubric which can be used to evaluate ethical reasoning, which is part of a collection of rubrics created to evaluate various learning outcomes such as intellectual and practical skills, personal and social responsibility, which. The ethical reasoning rubric is organized into sub-categories including “ethical self-awareness,” “understanding different ethical perspectives/ concepts, “ethical issue recognition,” “application of ethical perspectives/ concepts,” and “evaluation of different ethical perspectives/ concepts.”

Using this rubric as a guide can provide Child and Youth Care program instructors a measurable tool for evaluating complex concepts such as ethical practice. While generally applicable, it can be used as a starting point and adapted to meet the need of a given assignment, project, or activity to be more relevant and meaningful for students. For example, when evaluating a student’s understanding of the OACYC Code of Ethics (OACYC, 2020) case studies can be creating outlining different scenarios, from which students must apply their understanding and learning in a variety of ways. The description of the assignment or project would incorporate descriptive verbs from the affective domain taxonomy, and the evaluation would assess their awareness and understanding, application of information, tailoring the rubric to better fit with the assignment.

Using the rubric as a starting point, a student’s self-awareness, understanding of the concepts, ability to recognize an ethical dilemma or concern, as well as their ability to apply concepts/elements of the OACYC Code of Ethics can be evaluated in a measurable format along with providing individualized feedback.

While more research needs to take place around best practices for evaluating the affective domain in the field of Child and Youth Care and other helping professions, these examples provide a good starting point from which Child and Youth Care faculty and instructors can evaluate assignments and activities created to teach students about ethics and have students internalize learning to reflect in their beliefs and values as they enter the field. These examples and principles can be applied to any profession beyond Child and Youth Care where ethics and values are important to evaluate. Specific skills, ethical values, standards of practice, as well as professional conduct are among the pillars of the helping professions such as Early Childhood Education, social work, education, human services, criminal justice, in addition to STEM and health professions. A student’s understanding of information can be evaluated using learning outcomes based on the cognitive domain, but a student’s personal, internal synthesis and changes in beliefs and values are more appropriately and fulsomely evaluated using the affective domain within Bloom’s Taxonomy. The taxonomy was developed over 50 years ago; the time has come to update the assessments we use to reflect all domains of learning. By upgrading evaluation methods to accurately assess not only skill sets and understanding of information, but also how their values are shaped and transformed upon entering the field, we can support more than just academic success for our students. We can help to strengthen their personal and professional success throughout their career.

References

Adelson, J. L., & McCoach, D. B. (2011). Development and psychometric properties of the Math and Me Survey: Measuring third through sixth graders’ attitudes toward mathematics. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 44(4), 225–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175611418522

Allen, K., & Friedman, B.D. (2010). Affective learning: A taxonomy for teaching social work values. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 7(2).

Armstrong, P. (n.d.). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Center for Teaching, Vanderbilt University. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/

Association for Child and Youth Care Practice. (2010). Competencies for Professional Child & Youth Work Practitioners. https://www.cyccb.org/images/pdfs/2010_Competencies_for_Professional_CYW_Practitioners.pdf

Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2017). VALUE: Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education. https://www.umass.edu/oapa/sites/default/files/pdf/tools/rubrics/ethical_reasoning_value_rubric.pdf

Avci, E. (2017). Learning from experiences to determine quality in ethics education. International Journal of Ethics Education. 2, 3-16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40889-016-0027-6

Baker, J. D. (2004). An investigation of relationships among instructor immediacy and affective and cognitive learning in the online classroom. The Internet and Higher Education, 7, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2003.11.006

Batt, A. (2015). Teaching and evaluating the affective domain in paramedic education. Canadian Paramedicine. 38, 22-23.

Broussard, J. D. & Teng, E. J. (2019). Models for enhancing the development of experiential learning approaches within mobile health technologies. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 50(3). 195-203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pro0000234

Budd, D. (2020). Reflective practice in child and youth care. Canadian Scholars Press.

Burns, M. (2016). The self in child and youth care. Child Care Press.

Camelia, F., Ferris, T. L. J., & Cropley, D. H. (2018). Development and Initial Validation of an Instrument to Measure Students’ Learning About Systems Thinking: The Affective Domain. IEEE Systems Journal. 12(1). 115-124. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSYST.2015.2488022

Centre for Teaching Excellence. (n.d.) Bloom’s Taxonomy. University of Waterloo. Retrieved from: https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/sites/ca.centre-for-teaching-excellence/files/uploads/files/affective_domain_-_blooms_taxonomy.pdf

Garfat, T., Freeman, J., Gharabaghi, K., & Fulcher, L. (2019). Characteristics of a relational child and youth care approach. In Garfat, T., Fulcher, L., & Digney, J. (Ed.), Making Moments Meaningful in Child and Youth Care Practice (2nd ed., pp. 6-44). CYC-net Press.

Lee, L. (2019, July 18). The benefits of teaching ethical dilemmas. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/article/benefits-teaching-ethical-dilemmas

Ontario Association of Child and Youth Care. (2020). Code of Ethics. https://oacyc.org/code-of-ethics/

Oughton, J. & Pierre, E. (2002). Feeling the measure: Evaluating affective outcomes. https://oucqa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Oughton-Pierre-11.45-12.45-Seymour-Room-Presentation-Slide.pdf

Shaw, K. (2011). Child and Youth Care Education: On Discovering the Parallels to Practice. Relational Child and Youth Care Practice. 24(1/2).

Weston, A. (2011). A practical companion to ethics. Oxford University Press.

Wu, W.-H., Kao, H.-Y., Wu, S.-H., & Wei, C.-W. (2019). Development and Evaluation of Affective Domain Using Student’s Feedback in Entrepreneurial Massive Open Online Courses. Frontiers in Psychology, 10:1109. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01109

About the Author

Paola is a member of the Child and Youth Care faculty at Centennial College since 2016. She has been teaching since 2010, and has worked in the field of Child and Youth Care for over 15 years in community, mental health, school, hospital, and residential treatment settings.

Media Attributions

- Bloom’s Taxonomy: Affective Domain © Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Bloom’s Taxonomy: Affective Domain. © Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license