4 Yvonne Williams

A Sparkle of Light

Iraboty Kazi

Sunlight actually becomes part of a window; for while a painting is made visible by light falling on its surface, stained glass is revealed by outdoor light passing through the glass to the interior of the building. To paint a window so that it accepts this “partnership with the sun,” and is responsive to every passing cloud – even to the sparkle of light reflected from leaves moving in the wind, is to give it its full interest. It is then alive, and leaving the class of static art, becomes something not only in Space, but in Time.

— Yvonne Williams

A leader, educator, and one of the first women to establish her own career in the male-dominated practice of twentieth-century Canadian stained glass, Yvonne Williams (1901-1997) forged a distinct and influential style that contributed to the development of modern stained glass in North America.

Yvonne Williams was born on September 9, 1901 in Port of Spain, Trinidad to Canadian parents, John Sewell Williams and Elizabeth Catherine Kilgour Lockery. She later attributed her love of colour to her childhood on the tropical island. She showed interest in art at an early age, as she began “modelling in clay and plasticine” as a child. Later, from the ages of ten to sixteen, she took part in the Royal College of Art School programme, which she remembered “more as a development of seeing rather than expressing.”[1] In 1918, her family moved to Canada and settled in Grimsby, Ontario.[2] She enrolled at the Ontario College of Art (now Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD)) in 1922 to study sculpture but soon moved to painting because she “missed the colour terribly.”[3] She painted with the likes of Arthur Lismer, Fred Varley, and J.E.H. MacDonald and won the Governor General’s Gold Medal for excellence in life drawing and design. Williams’ increasing interest in stained glass led her to stay an additional year after her graduation to focus on metal and glass art with instructor Edith Grace Coombs (1890 – 1986). She graduated from college in 1926.

Her decision to pursue a career as a stained glass artist was, as she stated, “a peculiar choice for a career in 1927; more so for a woman, and even more so in Canada.”[4] She made her first window at Pringle & London Glaziers in Toronto in 1926 in partnership with the craftsman George London.[5] He later joined her workshop, and the two had a life-long working relationship. In the winter of 1927, Williams began work at the studio of F. J. Hollister, a prominent Toronto-based stained glass artist, but she soon moved on to study in studios in St. Louis and Philadelphia.[6] Initially, she struggled to establish her practice but after a six-month trip to England, France, and Italy, she returned home with the intent of receiving formal training in stained glass design. From 1928 to 1930, she apprenticed in Boston in the studio of Charles Connick (1875-1945), a well-known painter, muralist, and stained glass designer who championed the ideals of the Gothic Revival and whose style she emulated in her early works.[7] The two shared similar ideas about stained glass and Connick became a guiding figure throughout her life.

Following her return to Toronto, Williams opened her first studio in 1934 with Esther Johnson in a house she rented from Arthur Lismer,[8] whom she met at OCAD. She initially struggled to launch her career. With the deprivations of the Depression and competition from bigger commercial studios, Williams did artistic odd jobs and window decorating to make ends meet.[9] Interestingly, in her article with Jeffrey Kraegel, “In Partnership with the Sun: The Life and Work of Yvonne Williams,” glass artist Sarah Hall stated that “Yvonne claimed that the Great Depression was a good time to start a studio. Architects weren’t very busy, and had ample time to view her portfolio.”[10] Williams’ demonstration of stained glass techniques at the Canadian National Exhibition piqued the interest of an architect, Bruce Brown, who commissioned her to do two small windows in the Necropolis Chapel at Riverdale Cemetery, Toronto. This was followed by a commission for a window at Holy Rosary Church, Toronto and a growing number of commissions. As her reputation grew and the economy picked up, business got steadily better and by 1948, there was a two-year waiting list for her windows.

With a rising number of commissions, Williams designed and built a large studio on 3 Caribou Road in North Toronto in the late 1940s.[11] The Yvonne Williams Studio was in operation for nearly thirty years and produced over four hundred commissions for both public and private buildings – churches, schools, hospitals and residences – across the country from British Columbia to North West Territories.[12] The studio was recognized in and outside the industry for the high standard of quality of its productions. For example, writing in Mayfair 1954, Robert Fulford stated, “She stands as the Canadian leader of a school that is pushing stained glass past its traditional boundaries into the rewarding fields of symbolism and impressionism.”[13] The studio was also recognized in the Canadian stained glass community for its unique organization in a fashion akin to the European Art and Crafts glass houses, a departure from the strict hierarchy and sharply defined tasks of a traditional glass studio.[14] Many of the Williams Studio commissions were done collaboratively or by a single artist. Hall explains:

Artists working at the studio could also execute their own commissions there, with complete autonomy. Although the designs, cartoons and glass painting were done by the artists, the cutting, glazing and installations were done by craftsman George London. . . In dividing up the work at the studio, Yvonne relied on her magic formula, which was based on percentages for each part of the job of making a window. Thus the artist who cartooned a work would be paid for that part, while another would receive the portion for the painting, and so on.[15]

Williams invited artists such as Ellen Simon, Gustav Weisman, Rosemary Kilbourn, and Stephen Taylor to collaborate with her on numerous commissions, thus providing indispensable training and experience to younger artists.[16]

In addition to stained glass design, Williams was notable for her written works[17] on the value of creative stained glass and was in demand as a public speaker and educator. In the interest of engaging people in the artistic and studio process, she gave tours of her studio and invited clients and students to see how the work was produced.[18] “Through education, practice and evolution, Yvonne attained a distinct cohesion of technique and inspired artistic vision.”[19] Williams made no apology for what she called, “the egocentricity of artists.” She stated: “For stained glass artists, it’s the necessity to exist in divisions: half fine art and half handicraft; half philosophy and half business.”[20]

Although Williams’ commissions were largely of figurative compositions for religious sites, she created significant works for secular and private buildings. Regardless of the subject or the location, Williams maintained her high standards, experimented with abstract designs, and stressed the importance of “a partnership with the sun” for the project’s success; “It is then alive, and leaving the class of static art, becomes something not only in space, but in time.”[21] Williams’ artwork was highly influential in the development of modern stained glass in Canada. Firsthand observations of Medieval stained glass and the Gothic revivalist style of her mentor, Connick, inspired her early work in the 1930s and 1940s. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, her “windows show a continuous progress over the years, moving through various painting techniques, while the designs themselves move progressively towards abstraction.”[22] In her illustrious career, she brought attention to stained glass as a medium expressing the ideas of contemporary society.

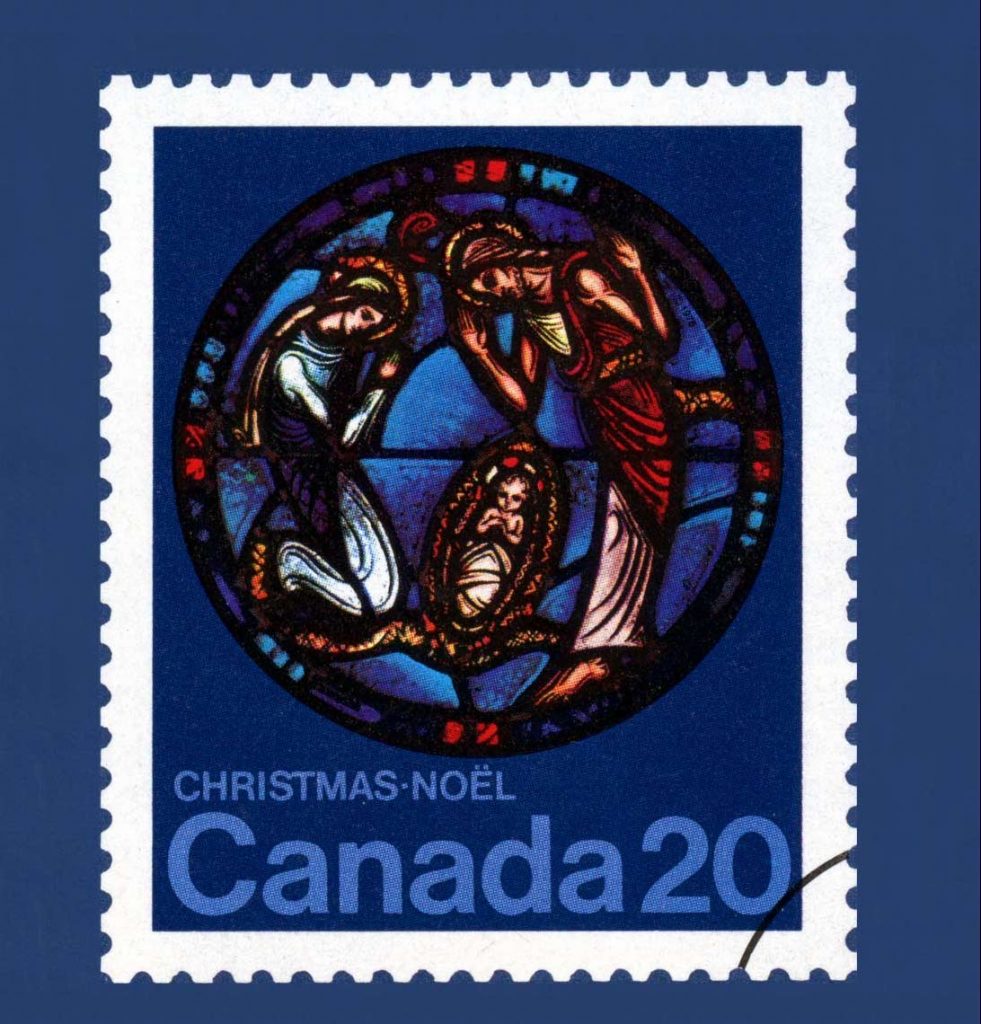

Williams’ innovative style and works in buildings throughout Canada have been recognized in the artistic and architectural communities. This brought her several prestigious awards, including the Allied Arts Medal from the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada and in 1965, election to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts.[23] In 1975, samples of her work were included in A Tribute to Ten Women Artists, an exhibition organized by the Sisler Gallery, Toronto, that featured other notable artists such as Paraskeva Clark, Yvonne McKague Housser, and Doris McCarthy.[24] In 1976, one of William’s stained glass designs was used for the twenty-cent stamp, and in 1997, her depiction of the nativity scene was printed on the fifty-two cent Christmas stamp. The 1976 stamp is on display in the stamp collection gallery at the Canadian Museum of History.

Her hundreds of commissions, her many awards, her pioneering reputation – all of these reveal a woman with a vision and the determination to follow it through. Underlying it all was profound artistry and an understanding and love for light and colour.[25] Even after her retirement, Williams continued to design windows and maintained an active interest in the work and ideas of younger artists following her pioneering career work.[26] She died on September 25, 1997, in Parry Sound, Ontario at the age of 96.

[1] Colin S. MacDonald, “Williams, Yvonne,” The Dictionary of Canadian Artists. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 2009.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Sarah Hall and Jeffrey Kraegel, “In Partnership with the Sun: The Life and Work of Yvonne Williams,” Sarah Hall Studio (Toronto), March/April 2000.

[4] Ibid.

[5] MacDonald, “Williams, Yvonne.”

[6] Hall and Kraegel, “In Partnership with the Sun.”

[7] MacDonald, “Williams, Yvonne.”

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid

[10] Hall and Kraegel, “In Partnership with the Sun.”

[11] MacDonald, “Williams, Yvonne.”

[12] Ibid

[13] Ibid

[14] Hall and Kraegel, “In Partnership with the Sun.”

[15] Ibid.

[16] MacDonald, “Williams, Yvonne.”

[17] Her written works include: “Stained Glass,” Bulletin of the Stained Glass Association of America 24.9 (Sept. 1929): 12-13; “Some Speculations on the Future of Stained Glass – A Canadian View,” Stained Glass 39 (Spring 1944): 21-23; “Processes and Craftsmanship in Stained Glass”, Journal, Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (August 1946): 199-201; with Ellen Simon. “The Stained Glass Windows of St. Michael and All Angels Church,” 1982.

[18] Artists: Williams, Yvonne,” Canadian Women Artists History Initiative. July 29, 2014.

[19] Hall and Kraegel, “In Partnership with the Sun.”

[20] McCarthy, Pearl. “Art and Artists.” Globe and Mail (Toronto) Dec. 12, 1936: 11.

[21] MacDonald, “Williams, Yvonne.”

[22] Hall and Kraegel, “In Partnership with the Sun.”

[23] Ibid.

[24] MacDonald, “Williams, Yvonne.”

[25] Hall and Kraegel, “In Partnership with the Sun.”

[26] MacDonald, “Williams, Yvonne.”