4 Labor, Material and Equipment Utilization

4.1 Historical Perspective

Good project management in construction must vigorously pursue the efficient utilization of labor, material and equipment. Improvement of labor productivity should be a major and continual concern of those who are responsible for cost control of constructed facilities. Materials management, which includes procurement, inventory, shop fabrication and field servicing, requires special attention for cost reduction. The use of new equipment and innovative methods has made possible wholesale changes in construction technologies in recent decades. Organizations which do not recognize the impact of various innovations and have not adapted to changing environments have justifiably been forced out of the mainstream of construction activities.

Observing the trends in construction technology presents a very mixed and ambiguous picture. On the one hand, many of the techniques and materials used for construction are essentially unchanged since the introduction of mechanization in the early part of the twentieth century. For example, a history of the Panama Canal construction from 1904 to 1914 argues that:

[T]he work could not have been done any faster or more efficiently in our day, despite all technological and mechanical advances in the time since, the reason being that no present system could possibly carry the spoil away any faster or more efficiently than the system employed. No motor trucks were used in the digging of the canal; everything ran on rails. And because of the mud and rain, no other method would have worked half so well. [1]

In contrast to this view of one large project, one may also point to the continual change and improvements occurring in traditional materials and techniques. Bricklaying provides a good example of such changes:

Bricklaying…is said not to have changed in thousands of years; perhaps in the literal placing of brick on brick it has not. But masonry technology has changed a great deal. Motorized wheelbarrows and mortar mixers, sophisticated scaffolding systems, and forklift trucks now assist the bricklayer. New epoxy mortars give stronger adhesion between bricks. Mortar additives and cold-weather protection eliminate winter shutdowns. [2]

Add to this list of existing innovations the recent emergence of commercial robotic bricklaying. Automated prototypes for masonry construction continue to be introduced. Iterative automation advances continue as well, including self-leveling pallets, and 3D printing. Technical change is certainly occurring in construction, although it may occur at a slower rate than in other sectors of the economy.

The United States and Canadian construction industries often point to factors which cannot be controlled by them as major explanatory factors in cost increases and lack of technical innovation. These include the imposition of restrictions for protection of the environment and historical districts, requirements for community participation in major construction projects, labor laws which allow union strikes to become a source of disruption, regulatory policies including building codes and zoning ordinances, and tax laws which inhibit construction abroad. However, the construction industry should bear a large share of blame for not realizing earlier that the technological edge held by the large U.S. construction firms has eroded in face of stiff foreign competition. Many past practices, which were tolerated when U.S. contractors had a technological lead, must now be changed in the face of stiff competition. Otherwise, the U.S. construction industry will continue to find itself in trouble. This holds true for Canadian firms.

With a strong technological base, there is no reason why the construction industry cannot catch up and reassert itself to meet competition wherever it may be. Individual design and/or construction firms must explore new ways to improve productivity for the future. Of course, operational planning (including implementation of “best practices”) for construction projects is still important, but such tactical planning has limitations and has reached the point of diminishing return because much that can be wrung out of the existing practices have already been tried. Project cost and schedule performance and project productivity continue to vary between projects, but they have not improved substantially over the last several decades. What is needed the most is strategic planning to usher in a revolution which can improve productivity by an order of magnitude or more. Strategic planning should look at opportunities and ask whether there are potential options along which new goals may be sought on the basis of existing resources. No one can be certain about the success of various development options for the design professions and the construction industry. However, with the availability of today’s high technology, some options have good potential of success because of the social and economic necessity which will eventually push barriers aside. Ultimately, decisions for action, not plans, will dictate future outcomes.

4.2 Labor Productivity

Productivity in construction is often broadly defined as output per labor hour. Since labor constitutes a large part of the construction cost, and the quantity of labor hours in performing a task in construction is more susceptible to the influence of management than are materials or capital, this productivity measure is often referred to as labor productivity. However, it is important to note that labor productivity is a measure of the overall effectiveness of an operating system in utilizing labor, equipment and capital to convert labor efforts into useful output, and it is not a measure of the capabilities of labor alone. For example, by investing in a piece of new equipment to perform certain tasks in construction, output may be increased for the same number of labor hours, thus resulting in higher labor productivity.

Construction output may be expressed in terms of functional units or constant dollars. In the former case, labor productivity is associated with units of product per labor hour, such as cubic meters of concrete placed per hour or kilometers of highway paved per hour. In the latter case, labor productivity is identified with value of construction (in constant dollars) per labor hour. The value of construction in this regard is not measured by the benefit of constructed facilities, but by construction cost. Labor productivity measured in this way requires considerable care in interpretation. For example, wage rates in construction declined in the US during the period 1970 to 1990, and since wages are an important component in construction costs, the value of construction put in place per hour of work declined as a result, suggesting lower productivity.

Productivity at the Job Site

Contractors and owners are often concerned with the labor activity at job sites. For this purpose, it is convenient to express labor productivity as functional units per labor hour for each type of construction task. However, even for such specific purposes, different levels of measure may be used. For example, cubic yards of concrete placed per hour is a lower level of measure than miles of highway paved per hour. Lower-level measures are more useful for monitoring individual activities and estimating project costs, while higher-level measures may be more convenient for developing industry-wide standards of performance.

While each contractor or owner is free to use its own system to measure labor productivity at a site, it is a good practice to set up a system which can be used to track productivity trends over time and in varied locations. Cost codes for categories of work must be standardized. Only the largest contractors have the discipline to do this. The data is typically rigorously protected as proprietary information. Considerable efforts are required to collect information regionally or nationally over a number of years to produce useful results. The productivity indices compiled from statistical data should include parameters such as the performance of major crafts, typical crew and equipment spreads (groups), effects of project size, type and location, degree of best practices implementation, and other major project performance influences. When unavailable internally, a source for this kind of data that has been available publicly for over one hundred years is the series of cost estimating manuals and indices published by RSMeans, such as their “Building construction costs with RSMeans data, 2022, Doheny, Matthew, editor.; R.S. Means Company, corporate body. 2021”. These can be purchased from the company’s web site or accessed through many university libraries which have purchased access to the data. The authors’ choice to share this information should not be taken as an endorsement. It can be useful if its limitations are understood. For example, the data may be updated less often that internal corporate data.

In order to develop industry-wide standards of performance, there must be a general agreement on the measures to be used for compiling data. Then, the job site productivity data collected by various contractors and owners can be correlated and analyzed to develop certain measures for each major segment of the construction industry. Thus, a contractor or owner can compare its performance with that of the industry average and discover performance relationships with different practices. Attempts to do this for some sectors of the construction industry have been ongoing for many years at the Construction Industry Institute associated with the University of Texas at Austin, and at times by other groups.

Productivity Factor

Labor productivity should not be confused with “productivity factor” or “PF”. The PF is a ratio of estimated productivity and actual productivity as measured on a particular project. It is widely used on larger pro jects to indicate whether the project or parts of the project are proceeding better or worse than planned, thus it serves as a sort of feedback for the project manager. It can be used as a leading indicator for future performance of the project, and it can be used to project final cost or duration to completion of the project, within confidence limits.

Productivity in the Construction Industry

Because of the diversity of the construction industry, a single index for the entire industry is neither meaningful nor reliable. Productivity indices may be developed for major segments of the construction industry nationwide and regionally if reliable statistical data can be obtained for separate industrial segments. For this general type of productivity measure, it is more convenient to express labor productivity as constant dollars per labor hours since dollar values are more easily aggregated from a large amount of data collected from different sources. The use of constant dollars allows meaningful approximations of the changes in construction output from one year to another when price deflators are applied to current dollars to obtain the corresponding values in constant dollars. However, since most construction price deflators are obtained from a combination of price indices for material and labor inputs, they reflect only the change of price levels and do not capture any savings arising from improved labor productivity. Such deflators tend to overstate increases in construction costs over a long period of time, and consequently understate the physical volume or value of construction work in years subsequent to the base year for the indices.

4.3 Factors Affecting Job-Site Productivity

Job-site productivity is influenced by many factors which can be characterized either as labor characteristics, project work conditions or as non-productive activities.

The labor characteristics include:

- age, skill and experience of workforce

- leadership and motivation of workforce

The project work conditions include among other factors:

- Job size and complexity

- Job site accessibility

- Labor availability

- Equipment utilization

- Contractual agreements

- Local climate

- Local cultural characteristics, particularly in foreign operations

The non-productive activities associated with a project may or may not be paid by the owner, depending on the contract terms, but they nevertheless take up potential labor resources which can otherwise be directed to the project. The non-productive activities include among other factors:

- Indirect labor required to maintain the progress of the project

- Rework for correcting incorrect or unsatisfactory work

- Temporary work stoppage due to inclement weather or material shortage

- Time off for union activities

- Absentee time, including late start and early quits

- Non-working holidays

- Strikes

Each category of factors affects the productive labor available to a project as well as the on-site labor efficiency.

Productive time (comprised of productive activities) is often called “direct work” or “tool time”. Activity analysis is a well-established industry practice for improving the direct work rate. Typical direct work rates for different trades are identified in Shahtaheri et al.

Strategic and tactical actions that can be taken to improve job-site productivity are described in “Construction Productivity” (NAC Executive Insights – Construction Execution, September 2, 2022, by B. Prieto).

Labor Characteristics

Performance analysis is a common tool for assessing worker quality and contribution. Factors that might be evaluated include:

- Quality of Work – caliber of work produced or accomplished.

- Quantity of Work – volume of acceptable work

- Job Knowledge – demonstrated knowledge of requirements, methods, techniques and skills involved in doing the job and in applying these to increase productivity.

- Related Work Knowledge – knowledge of effects of work upon other areas and knowledge of related areas which have influence on assigned work.

- Judgment – soundness of conclusions, decisions and actions.

- Initiative – ability to take effective action without being told.

- Resource Utilization – ability to delineate project needs and locate, plan and effectively use all resources available.

- Dependability – reliability in assuming and carrying out commitments and obligations.

- Analytical Ability – effectiveness in thinking through a problem and reaching sound conclusions.

- Communicative Ability – effectiveness in using oral and written communications and in keeping subordinates, associates, superiors and others adequately informed.

- Interpersonal Skills – effectiveness in relating in an appropriate and productive manner to others.

- Ability to Work Under Pressure – ability to meet tight deadlines and adapt to changes.

- Security Sensitivity – ability to handle confidential information appropriately and to exercise care in safeguarding sensitive information.

- Safety Consciousness – has knowledge of good safety practices and demonstrates awareness of own personal safety and the safety of others.

- Profit and Cost Sensitivity – ability to seek out, generate and implement profit-making ideas.

- Planning Effectiveness – ability to anticipate needs, forecast conditions, set goals and standards, plan and schedule work and measure results.

- Leadership – ability to develop in others the willingness and desire to work towards common objectives.

- Delegating – effectiveness in delegating work appropriately.

- Development People – ability to select, train and appraise personnel, set standards of performance, and provide motivation to grow in their capacity. < li>Diversity (Equal Employment Opportunity) – ability to be sensitive to the needs of minorities, females and other protected groups and to demonstrate affirmative action in responding to these needs.

These different factors could each be assessed on a three-point scale: (1) recognized strength, (2) meets expectations, (3) area needing improvement. Examples of work performance in these areas might also be provided.

Project Work Conditions and Productivity Factor (PF)

Job-site labor productivity can be estimated either for each craft (carpenter, bricklayer, etc.) or each type of construction (residential housing, processing plant, etc.) and each category of work (e.g. pipe welding, concrete placement, etc.) under a specific set of work conditions. Thus, base labor productivity rates may be defined for a project for both estimating the cost of the project and for calculating the PF described earlier. The PF is a measure of the relative labor efficiency of a project. As noted earlier, it is related to project performance.

The effects of various factors related to work conditions on a new project can be estimated in advance, some more accurately than others. For example, for very large construction projects, the labor productivity index tends to decrease as the project size and/or complexity increase because of logistic problems and the “learning” that the work force must undergo before adjusting to the new environment. Job-site accessibility often may reduce the labor productivity index if the workers must perform their jobs in round about ways, such as avoiding traffic in repaving the highway surface or maintaining the operation of a plant during renovation. Labor availability in the local market is another factor. Shortage of local labor will force the contractor to bring in non-local labor or schedule overtime work or both. In either case, the labor efficiency will be reduced in addition to incurring additional expenses. The degree of equipment utilization and mechanization of a construction project clearly will have direct bearing on job-site labor productivity. The contractual agreements play an important role in the utilization of union or non-union labor, the use of subcontractors and the degree of field supervision, all of which will impact job-site labor productivity. Since on-site construction essentially involves outdoor activities, the local climate will influence the efficiency of workers directly. In foreign operations, the cultural characteristics of the host country should be observed in assessing the labor efficiency.

Many of these productivity influencing factors are also described in “Factors Affecting Productivity” (NAC Executive Insights – Construction Execution, September 2, 2022, by B. Prieto), and in “Barriers to Productivity – An Overview” (NAC Executive Insights – Construction Execution, September 2, 2022, by B. Prieto).

Non-Productive Activities

The non-productive activities associated with a project should also be examined in order to examine the productive labor yield, which is defined as the “rolled up” (overall) ratio of direct labor hours devoted to the completion of a project to the potential labor hours. The direct labor hours are estimated on the basis of the best possible conditions at a job site by excluding all factors which may reduce the productive labor yield. For example, in the repaving of a highway surface, the flagmen required to divert traffic represent indirect labor which does not contribute to the labor efficiency of the paving crew if the highway is closed to the traffic. Similarly, for large projects in remote areas, indirect labor may be used to provide housing and infrastructure for the workers hired to supply the direct labor for a project. The labor hours spent on rework to correct unsatisfactory original work represent extra time taken away from potential labor hours. The labor hours related to such activities must be deducted from the potential labor hours in order to obtain the actual productive labor yield.

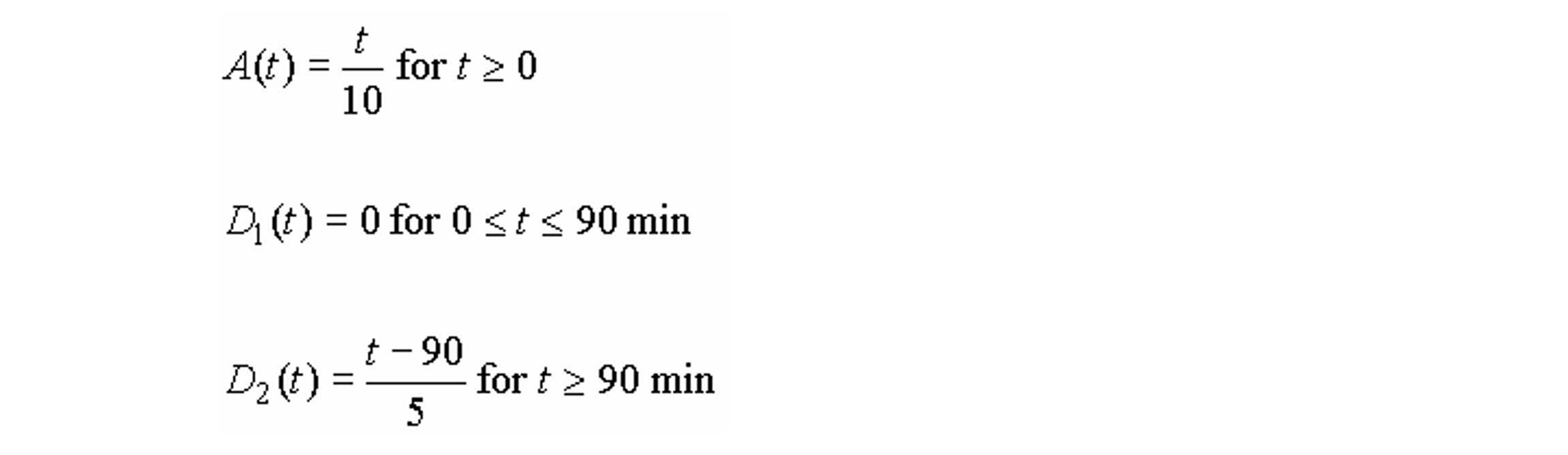

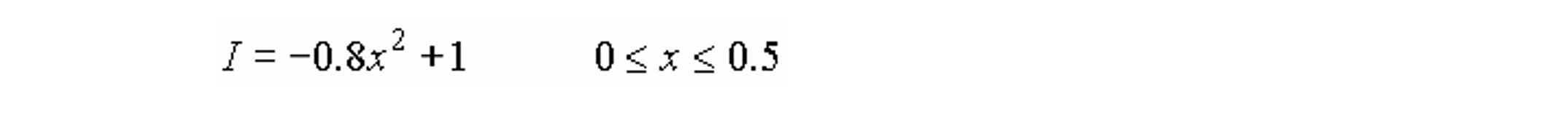

Example 4-1: Effects of job size on productivity

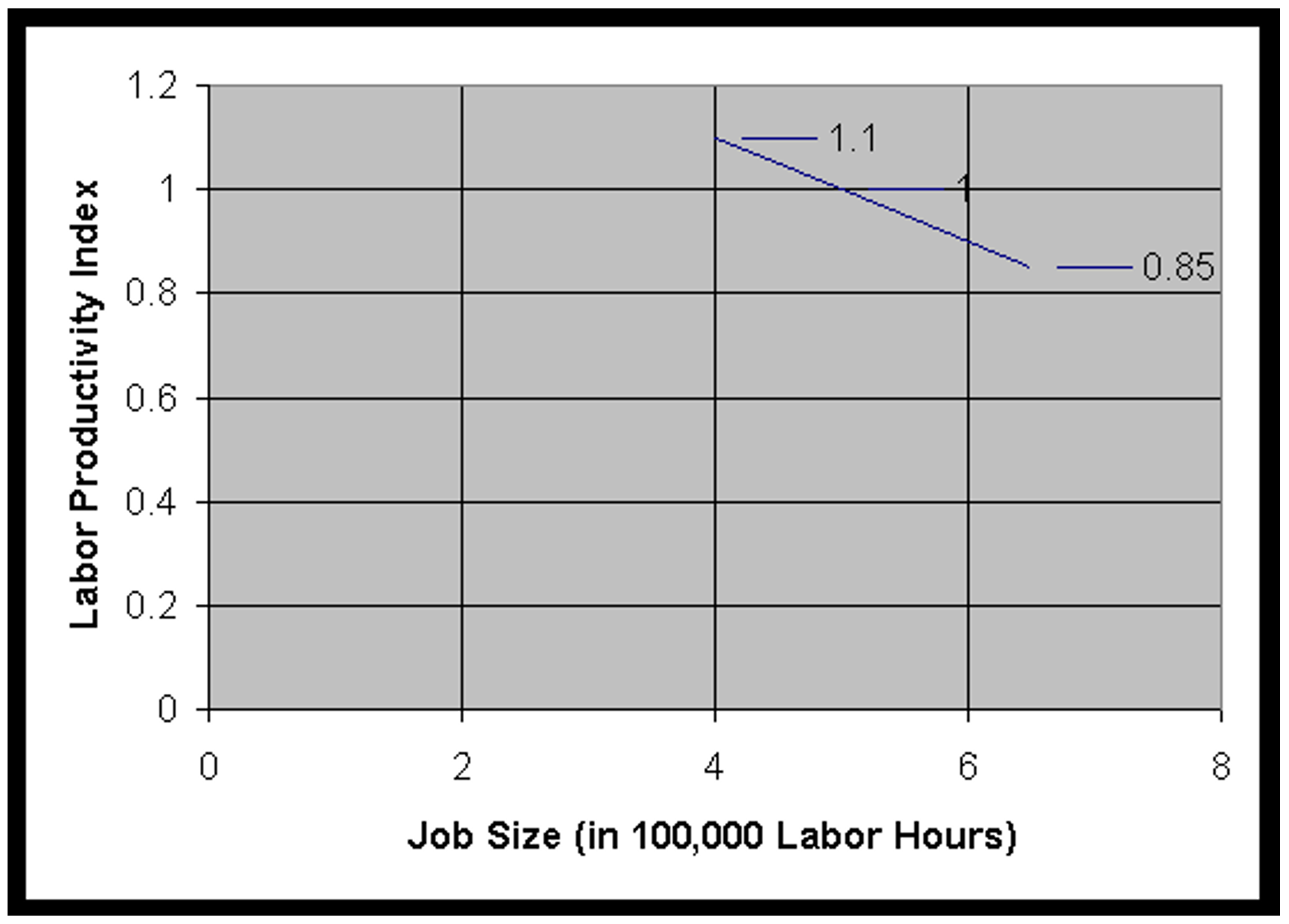

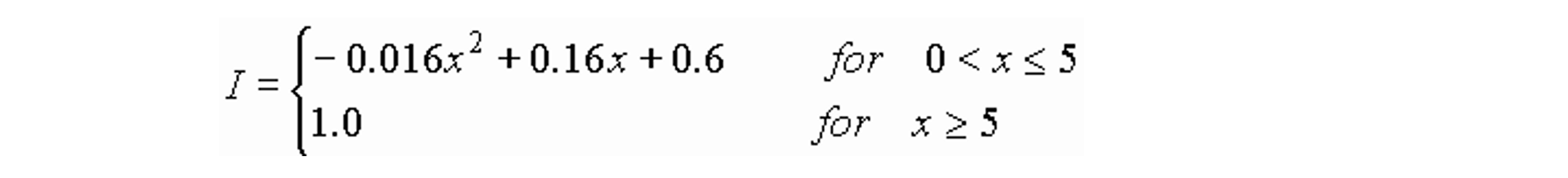

A contractor has established that under a set of “standard” work conditions for building construction, a job requiring 500,000 labor hours is considered standard in determining the base labor productivity. All other factors being the same, the labor productivity index will increase to 1.1 or 110% for a job requiring only 400,000 labor-hours. Assuming that a linear relation exists for the range between jobs requiring 300,000 to 700,000 labor hours as shown in Figure 4-1, determine the labor productivity index for a new job requiring 650,000 labor hours under otherwise the same set of work conditions.

Figure 4-1: Illustrative Relationship between Productivity Index and Job Size

The labor productivity index I for the new job can be obtained by linear interpolation of the available data as follows:

This implies that labor is 15% less productive on the large job than on the standard project.

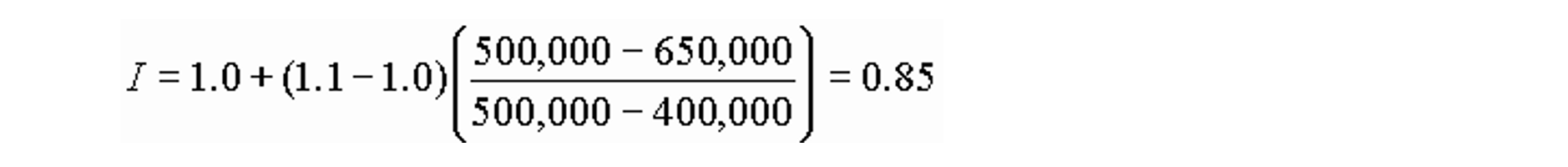

Example 4-2: Productive labor yield [3]

In the construction of an off-shore oil drilling platform, the potential labor hours were found to be L = 7.5 million hours. Of this total, the non-productive activities expressed in thousand labor hours were as follows:

-

- A = 417 for holidays and strikes

- B = 1,415 for absentees (i.e. vacation, sick time, etc.)

- C = 1,141 for temporary stoppage (i.e. weather, waiting, union activities, etc.)

- D = 1,431 for indirect labor (i.e. building temporary facilities, cleaning up the site, rework to correct errors, etc.)

Determine the productive labor yield after the above factors are taken into consideration.

Example 4-3: Utilization of on-site worker’s time

An example illustrating the effects of indirect labor requirements which limit productive labor by a typical craftsman on the job site was given by R. Tucker with the following percentages of time allocation: [4]

|

Productive time |

40% 20% |

In this estimate, as much time is spent on productive work as on delays due to management and inefficiencies due to antiquated work methods.

4.4 Labor Relations in Construction

The market demand in construction fluctuates greatly, often within short periods and with uneven distributions among geographical regions. Even when the volume of construction is relatively steady, some types of work may decline in importance while other types gain. Under an unstable economic environment, employers in the construction industry place great value on flexibility in hiring and laying off workers as their volumes of work wax and wane. On the other hand, construction workers sense their insecurity under such circumstances and attempt to limit the impacts of changing economic conditions through labor organizations.

There are many crafts in the construction labor forces, but most specialty contractors (e.g. mechanical or electrical contractors) hire from only a few of these crafts to satisfy their needs. Because of the peculiar characteristics of employment conditions, employers and workers are placed in a more intimate relationship than in many other industries. Labor and management arrangements in the construction industry include both unionized and non-unionized operations which compete for future dominance. Dramatic shifts in unionization can occur. For example, the fraction of trade union members in the construction industry declined from 42% in 1992 to 26% in 2000 in Australia, a 40% decline in 8 years. The fraction of the industry unionized in the US declined from about 41.4% in 1966 to 13.1% in 2005 according to Belman et al (2006). Unionization in construction remains a highly regionalized phenomenon in the US. According to Amick et al (2015) the percent of construction workers in Canada in 2012 who were unionized was 39%. It remains higher than the US, however it also varies by province.

Unionized Construction

The craft unions work with construction contractors using unionized labor through various market institutions such as jurisdiction rules, apprenticeship programs, and the referral system. Craft unions with specific jurisdiction rules for different trades set uniform hourly wage rates for journeymen and offer formal apprenticeship training to provide common and equivalent skill for each trade. Contractors, through the contractors’ associations, enter into legally binding collective bargaining agreements with one or more of the craft unions in the construction trades. The system which binds both parties to a collective bargaining agreement is referred to as the “union shop”. These agreements obligate a contractor to observe the work jurisdictions of various unions and to hire employees through a union operated referral system commonly known as the hiring hall.

The referral systems operated by union organizations are required to observe several conditions:

- All qualified workers reported to the referral system must be made available to the contractor without discrimination on the basis of union membership or other relationship to the union. The “closed shop” which limits referral to union members only is now illegal in the US.

- The contractor reserves the right to hire or refuse to hire any worker referred by the union on the basis of his or her qualifications.

- The referral plan must be posted in public, including any priorities of referrals or required qualifications.

While these principles must prevail, referral systems operated by labor organizations differ widely in the construction industry.

Contractors and craft unions must negotiate not only wage rates and working conditions, but also hiring and apprentice training practices. The purpose of trade jurisdiction is to encourage considerable investment in apprentice training on the part of the union so that the contractor will be protected by having only qualified workers perform the job even though such workers are not permanently attached to the contractor and thus may have no sense of security or loyalty. The referral system is often a rapid and dependable source of workers, particularly for a contractor who moves into a new geographical location or starts a new project which has high fluctuations in demand for labor. By and large, the referral system has functioned smoothly in providing qualified workers to contractors, even though some other aspects of union operations are not as well accepted by contractors.

Non-Unionized Construction

Since the 1980’s, non-union contractors have entered and prospered in an industry which previously had a long tradition of unionization. Non-union operations in construction are referred to as “open shops.” However, in the absence of collective bargaining agreements, many contractors operate under policies adopted by non-union contractors’ associations. This practice is referred to as “merit shop”, which follows substantially the same policies and procedures as collective bargaining although under the control of a non-union contractors’ association without union participation. Other contractors may choose to be totally “unorganized” by not following either union shop or merit shop practices.

In the US, the operations of the merit shop are national in scope, except for the local or state apprenticeship and training plans. The comprehensive plans of the contractors’ association apply to all employees and crafts of a contractor regardless of their trades. Under such operations, workers have full rights to move through the nation among member contractors of the association. Thus, the non-union segment of the industry is organized by contractors’ associations into an integral part of the construction industry. However, since merit shop workers are employed directly by the construction firms, they have a greater loyalty to the firm, and recognize that their own interest will be affected by the financial health of the firm.

Playing a significant role in the early growth and continued expansion of merit shop construction is the Associated Builders and Contractors association. The advantages of merit shops as claimed by its advocates are:

- the ability to manage their own work force

- flexibility in making timely management decisions

- the emphasis on making maximum usage of local labor force

- the emphasis on encouraging individual work advancement through continued development of skills

- the shared interest that management and workers have in seeing an individual firm prosper.

By shouldering the training responsibility for producing skill workers, primarily through the NCCER, the merit shop contractors have deflected the most serious complaints of users and labor that used to be raised against the open shop. On the other hand, the use of mixed crews of skilled workers and multi-skilled workers at a job site by merit shop contractors enables them to remove a major source of inefficiencies caused by the exclusive jurisdiction practiced in the union shop, namely the idea that only members of a particular union should be permitted to perform any given task in construction. As a result, merit shop contractors are able to exert a beneficial influence on productivity and cost-effectiveness of construction projects.

The unorganized form of open shop is found primarily in housing construction where a large percentage of workers are characterized as unskilled helpers. The skilled workers in various crafts are developed gradually through informal apprenticeships while serving as helpers. This form of open shop is not expected to expand beyond the type of construction projects in which highly specialized skills are not required.

Construction Trades Training in Canada

The trades in Canada are trained and organized slightly differently than the US. A rough equivalent to the merit shop in Canada would be the Red Seal certification, that allows construction craft workers to travel between provinces with their certifications recognized in the other provinces. Additionally, in Canada construction craft workers can belong to the organized group called the CLAC. In Quebec, all construction workers are organized under one union structure called the Commission de la construction du Québec. While some unions can be international, such as the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and have cross-border training opportunities, training in each province is managed differently. For example, in Ontario training centers are open to both unionized and open shop workers and are partly subsidized by the provincial government. Many trades are certified in Ontario, and certification requires progression through the apprenticeship program and passing standard exams.

4.5 Problems in Collective Bargaining

In the organized building trades in North American construction, the primary unit is the international union, which is an association of local unions in the United States and Canada. Although only the international unions have the power to issue or remove charters and to organize or combine local unions, each local union has considerable degrees of autonomy in the conduct of its affairs, including the negotiation of collective bargaining agreements. The business agent of a local union is an elected official who is the most important person in handling the day-to-day operations on behalf of the union. The contractors’ associations representing the employers vary widely in composition and structure, particularly in different geographical regions. In general, local contractors’ associations are considerably less well organized than the union with which they deal, but they try to strengthen themselves through affiliation with state and national organizations. Typically, collective bargaining agreements in construction are negotiated between a local union in a single craft and the employers of that craft as represented by a contractors’ association, but there are many exceptions to this pattern. For example, a contractor may remain outside the association and negotiate independently of the union, but it might not obtain a better agreement than the association.

Because of the great variety of bargaining structures in which the union and contractors’ organization may choose to stage negotiations, there are many problems arising from jurisdictional disputes and other causes. Given the traditional rivalries among various crafts and the ineffective organization of some of contractors’ associations, coupled with the lack of adequate mechanisms for settling disputes, some possible solutions to these problems deserve serious attention: [5]

Regional Bargaining

Currently, the geographical area in a collective bargaining agreement does not necessarily coincide with the territory of the union and contractors’ associations in the negotiations. There are overlapping of jurisdictions as well as territories, which may create successions of contract termination dates for different crafts. Most collective bargaining agreements are negotiated locally, but regional agreements with more comprehensive coverage embracing a number of states have been established. The role of national union negotiators and contractors’ representatives in local collective bargaining is limited. The national agreement between international unions and a national contractor normally binds the contractors’ association and its bargaining unit. Consequently, the most promising reform lies in the broadening of the geographic region of an agreement in a single trade without overlapping territories or jurisdictions.

Multi-craft Bargaining

The treatment of interrelationships among various craft trades in construction presents one of the most complex issues in the collective bargaining process. Past experience on project agreements has dealt with such issues successfully in that collective bargaining agreements are signed by a group of craft trade unions and a contractor for the duration of a project. Project agreements may reference other agreements on particular points, such as wage rates and fringe benefits, but may set their own working conditions and procedures for settling disputes including a commitment of no-strike and no-lockout. This type of agreement may serve as a starting point for multi-craft bargaining on a regional, non-project basis.

Improvement of Bargaining Performance

Although both sides of the bargaining table are to some degree responsible for the success or failure of negotiation, contractors have often been responsible for the poor performance of collective bargaining in construction in recent years because local contractors’ associations are generally less well organized and less professionally staffed than the unions with which they deal. Legislation providing for contractors’ association accreditation as an exclusive bargaining agent has now been provided in several provinces in Canada. It provides a government board that could hold hearings and establish an appropriate bargaining unit by geographic region or sector of the industry, on a single-trade or multi-trade basis.

4.6 Materials Management

Materials management is an important element in project planning and control. Materials represent a major expense in construction, so minimizing procurement or purchase costs presents important opportunities for reducing costs. Poor materials management can also result in large and avoidable costs during construction. First, if materials are purchased early, capital may be tied up and interest charges incurred on the excess inventory of materials. Even worse, materials may deteriorate during storage or be stolen unless special care is taken. For example, electrical equipment often must be stored in waterproof locations. Second, delays and extra expenses may be incurred if materials required for activities are not available. Accordingly, ensuring a timely flow of material is an important concern of project managers.

Materials management is not just a concern during the monitoring stage in which construction is taking place. Decisions about material procurement may also be required during the initial planning and scheduling stages. For example, activities can be inserted in the project schedule to represent purchasing of major items such as elevators for buildings. The availability of materials may greatly influence the schedule in projects with a fast track or very tight time schedule: sufficient time for obtaining the necessary materials must be allowed. In some cases, more expensive suppliers or shippers may be employed to save time.

Materials management is also a problem at the organization level if central purchasing and inventory control is used for standard items. In this case, the various projects undertaken by the organization would present requests to the central purchasing group. In turn, this group would maintain inventories of standard items to reduce the delay in providing material or to obtain lower costs due to bulk purchasing. This organizational materials management problem is analogous to inventory control in any organization facing continuing demand for particular items.

Materials ordering problems lend themselves particularly well to computer-based systems to insure the consistency and completeness of the purchasing process. In the manufacturing realm, the use of automated materials requirements planning systems is common. In these systems, the master production schedule, inventory records and product component lists are merged to determine what items must be ordered, when they should be ordered, and how much of each item should be ordered in each time period. The heart of these calculations is simple arithmetic: the projected demand for each material item in each period is subtracted from the available inventory. When the inventory becomes too low, a new order is recommended. For items that are non-standard or not kept in inventory, the calculation is even simpler since no inventory must be considered. With a materials requirement system, much of the detailed record keeping is automated and project managers are alerted to purchasing requirements.

For an additional perspective on materials management refer to “Materials Management” (NAC Executive Insights – Procurement and Supply Chain, June 21, 2021, by B. Prieto). Prieto lists common categories of construction materials, list functional activities in materials management, and explains concepts such as expediting, Supplier Quality Surveillance (SQS), logistics and filed materials management. There are nine Executive Insights in the NAC Procurement and Supply Chain site.

Example 4-4: Examples of benefits for materials management systems.[6]

From a study of twenty heavy construction sites, the following benefits from the introduction of materials management systems were noted:

-

- In one project, a 6% reduction in craft labor costs occurred due to the improved availability of materials as needed on site. On other projects, an 8% savings due to reduced delay for materials was estimated.

- A comparison of two projects with and without a materials management system revealed a change in productivity from 1.92 man-hours per unit without a system to 1.14 man-hours per unit with a new system. Again, much of this difference can be attributed to the timely availability of materials.

- Warehouse costs were found to decrease 50% on one project with the introduction of improved inventory management, representing a savings of $ 92,000. Interest charges for inventory also declined, with one project reporting a cash flow savings of $ 85,000 from improved materials management.

Against these various benefits, the costs of acquiring and maintaining a materials management system has to be compared. However, management studies suggest that investment in such systems can be quite beneficial.

A summary of five case studies published in 2014 gives an updated perspective as well.

4.7 Material Procurement and Delivery

The main sources of information for feedback and control of material procurement are requisitions, bids and quotations, submittals, purchase orders and subcontracts, shipping and receiving documents, and invoices. For projects involving the large-scale use of critical resources, the owner may initiate the procurement procedure even before the selection of a constructor in order to avoid shortages and delays, particularly for large and strategic engineered-equipment items such as turbines. Under ordinary circumstances, the constructor will handle the procurement to shop for materials with the best price/performance characteristics specified by the designer. Some overlapping and rehandling in the procurement process is unavoidable, but it should be minimized to insure timely delivery of the materials in good condition.

Where the contractor takes a lead role on a large complex project, a contracting strategy called Engineer-Procure-Construct (EPC) is often chosen, which elevates the key role of the procurement function in ensuring project success. Some contractors as referred to as EPC contractors. They tend to be highly concentrated in the industrial construction sector.

The materials for delivery to and from a construction site may be broadly classified as: (1) bulk materials, (2) standard off-the-shelf materials, and (3) fabricated members or units. The process of delivery, including transportation, field storage and installation will be different for these classes of materials. The equipment needed to handle and haul these classes of materials will also be different.

Bulk materials refer to materials in their natural or semi-processed state, such as earthwork to be excavated, wet concrete mix, etc. which are usually encountered in large quantities in construction. Some bulk materials such as earthwork or gravels may be measured in bank (solid in situ) volume. Obviously, the quantities of materials for delivery may be substantially different when expressed in different measures of volume, depending on the characteristics of such materials.

Hangers, standard piping and valves are typical examples of standard off-the-shelf materials which are used extensively in the chemical processing industry. Since standard off-the-shelf materials can easily be stockpiled, the delivery process is relatively simple. Pipe-spools on the other hand are considered engineered and fabricated materials.

Fabricated members such as pipe-spools, steel beams and columns for buildings are pre-processed in a shop to simplify the field erection procedures. Welded or bolted connections are attached partially to the members which are cut to precise dimensions for adequate fit. Similarly, steel tanks and pressure vessels are often partly or fully fabricated before shipping to the field. In general, if the work can be done in the shop where working conditions can better be controlled, it is advisable to do so, provided that the fabricated members or units can be shipped to the construction site in a satisfactory manner at a reasonable cost.

As a further step to simplify field assembly, an entire wall panel including plumbing and wiring or even an entire room may be prefabricated and shipped to the site. While the field labor is greatly reduced in such cases, “materials” for delivery are in fact manufactured products with value added by another type of labor. With modern means of transporting construction materials and fabricated units, the percentages of costs on direct labor and materials for a project may change if more prefabricated units are introduced in the construction process. Taken further, this strategy merges into modularization.

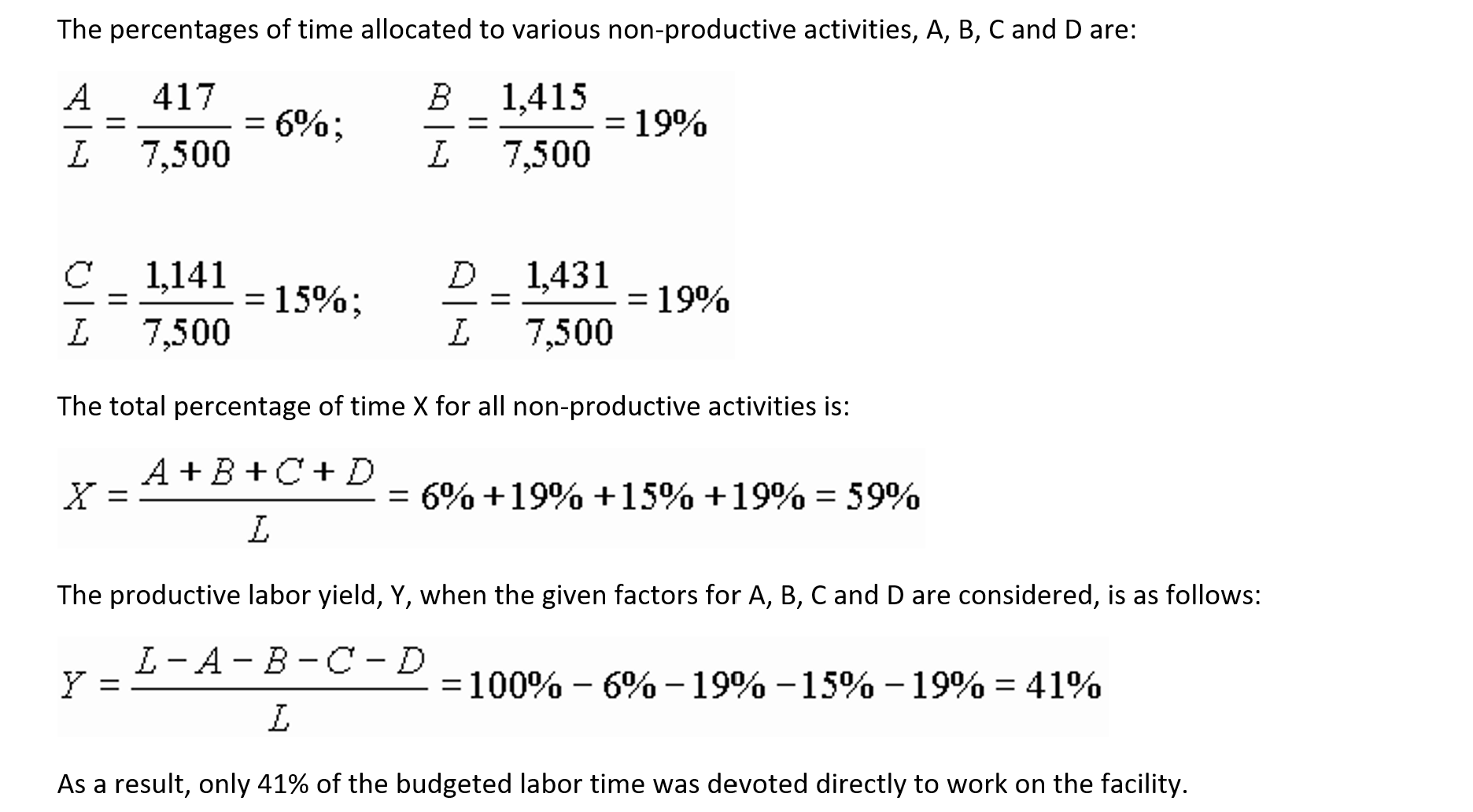

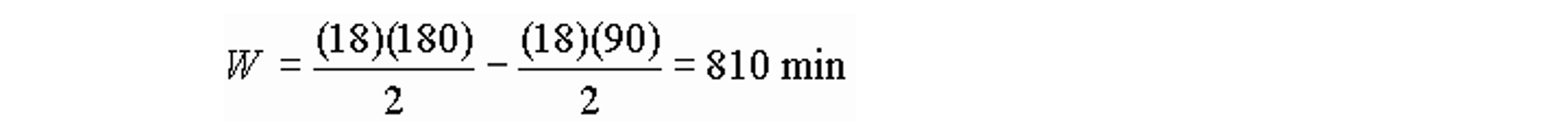

Example 4-5: Freight delivery for the Alaska Pipeline Project [7]

The freight delivery system for the Alaska pipeline project was set up to handle 600,000 tons of materials and supplies. This tonnage did not include the pipes which comprised another 500,000 tons and were shipped through a different routing system.

The complexity of this delivery system is illustrated in Figure 4-2. The rectangular boxes denote geographical locations. The points of origin represent plants and factories throughout the US and elsewhere. Some of the materials went to a primary staging point in Seattle and some went directly to Alaska. There were five ports of entry: Valdez, Anchorage, Whittier, Seward and Prudhoe Bay. There was a secondary staging area in Fairbanks and the pipeline itself was divided into six sections. Beyond the Yukon River, there was nothing available but a dirt road for hauling. The amounts of freight in thousands of tons shipped to and from various locations are indicated by the numbers near the network branches (with arrows showing the directions of material flows) and the modes of transportation are noted above the branches. In each of the locations, the contractor had supervision and construction labor to identify materials, unload from transport, determine where the material was going, repackage if required to split shipments, and then re-load material on outgoing transport.

Figure 4-2: Freight Delivery for the Alaska Pipeline Project

Example 4-6: Process plant equipment procurement [8]

The procurement and delivery of bulk materials items such as piping electrical and structural elements involves a series of activities if such items are not standard and/or in stock. The times required for various activities in the procurement of such items might be estimated to be as follows:

|

Activities |

Duration |

Cumulative |

|

Requisition ready by designer |

0 |

0 |

As a result, this type of equipment procurement will typically require four to nine months. Slippage or contraction in this standard schedule is also possible, based on such factors as the extent to which a fabricator is busy.

4.8 Inventory Control

Once goods are purchased, they represent an inventory used during the construction process. The general objective of inventory control is to minimize the total cost of keeping the inventory while making trade-offs among the major categories of costs: (1) purchase costs, (2) ordering cost, (3) holding costs, and (4) unavailable cost. These cost categories are interrelated since reducing cost in one category may increase cost in others. The costs in all categories generally are subject to considerable uncertainty.

Purchase Costs

The purchase cost of an item is the unit purchase price from an external source including transportation and freight costs. For construction materials, it is common to receive discounts for bulk purchases, so the unit purchase cost declines as quantity increases. These reductions may reflect manufacturers’ marketing policies, economies of scale in the material production, or scale economies in transportation. There are also advantages in having homogeneous materials. For example, a bulk order to ensure the same color or size of items such as bricks may be desirable. Accordingly, it is usually desirable to make a limited number of large purchases for materials. In some cases, organizations may consolidate small orders from several different projects to capture such bulk discounts; this is a basic saving to be derived from a central purchasing office.

The cost of materials is based on prices obtained through effective bargaining. Unit prices of materials depend on bargaining leverage, quantities, and delivery time. Organizations with potential for long-term purchase volume can command better bargaining leverage. While orders in large quantities may result in lower unit prices, they may also increase holding costs and thus cause problems in cash flow. Requirements of short delivery time can also adversely affect unit prices. Furthermore, design characteristics which include items of odd sizes or shapes should be avoided. Since such items normally are not available in the standard stockpile, purchasing them causes higher prices.

The transportation costs are affected by shipment sizes and other factors. Shipment by the full load of a carrier often reduces prices and assures quicker delivery, as the carrier can travel from the origin to the destination of the full load without having to stop for delivering part of the cargo at other stations. Avoiding transshipment is another consideration in reducing shipping cost. While the reduction in shipping costs is a major objective, the requirements of delicate handling of some items may favor a more expensive mode of transportation to avoid breakage and replacement costs.

Ordering Cost

The ordering cost reflects the administrative expense of issuing a purchase order to an outside supplier. Ordering costs include expenses of making requisitions, analyzing alternative vendors, writing purchase orders, receiving materials, inspecting materials, checking on orders, and maintaining records of the entire process. Ordering costs are usually only a small portion of total costs for material management in construction projects, although ordering may require substantial time.

Holding Costs

The holding costs or carrying costs are primarily the result of capital costs, handling, storage, obsolescence, shrinkage and deterioration. Capital cost results from the opportunity cost or financial expense of capital tied up in inventory. Once payment for goods is made, borrowing costs are incurred or capital must be diverted from other productive uses. Consequently, a capital carrying cost is incurred equal to the value of the inventory during a period multiplied by the interest rate obtainable or paid during that period. Note that capital costs only accumulate when payment for materials occurs; many organizations attempt to delay payments as long as possible to minimize such costs. Handling and storage represent the movement and protection charges incurred for materials. Storage costs also include the disruption caused to other project activities by large inventories of materials that get in the way. Obsolescence is the risk that an item will lose value because of changes in specifications. Shrinkage is the decrease in inventory over time due to theft or loss. Deterioration reflects a change in material quality due to age or environmental degradation. Many of these holding cost components are difficult to predict in advance; a project manager knows only that there is some chance that specific categories of cost will occur. In addition to these major categories of cost, there may be ancillary costs of additional insurance, taxes (many states treat inventories as taxable property), or additional fire hazards. As a general rule, holding costs will typically represent 20 to 40% of the average inventory value over the course of a year; thus if the average material inventory on a project is $ 1 million over a year, the holding cost might be expected to be $200,000 to $400,000.

Unavailability Cost

The unavailability cost is incurred when a desired material is not available at the desired time. In manufacturing industries, this cost is often called the stockout or depletion cost. Shortages may delay work, thereby wasting labor resources or delaying the completion of the entire project. Again, it may be difficult to forecast in advance exactly when an item may be required or when a shipment will be received. While the project schedule gives one estimate, deviations from the schedule may occur during construction. Moreover, the cost associated with a shortage may also be difficult to assess; if the material used for one activity is not available, it may be possible to assign workers to other activities and, depending upon which activities are critical, the project may not be delayed.

4.9 Trade-offs of Costs in Materials Management

To illustrate the type of trade-offs encountered in materials management, suppose that a particular item is to be ordered for a project. The amount of time required for processing the order and shipping the item is uncertain. Consequently, the project manager must decide how much lead time to provide in ordering the item. Ordering early and thereby providing a long lead time will increase the chance that the item is available when needed, but it increases the costs of inventory and the chance of spoilage on site.

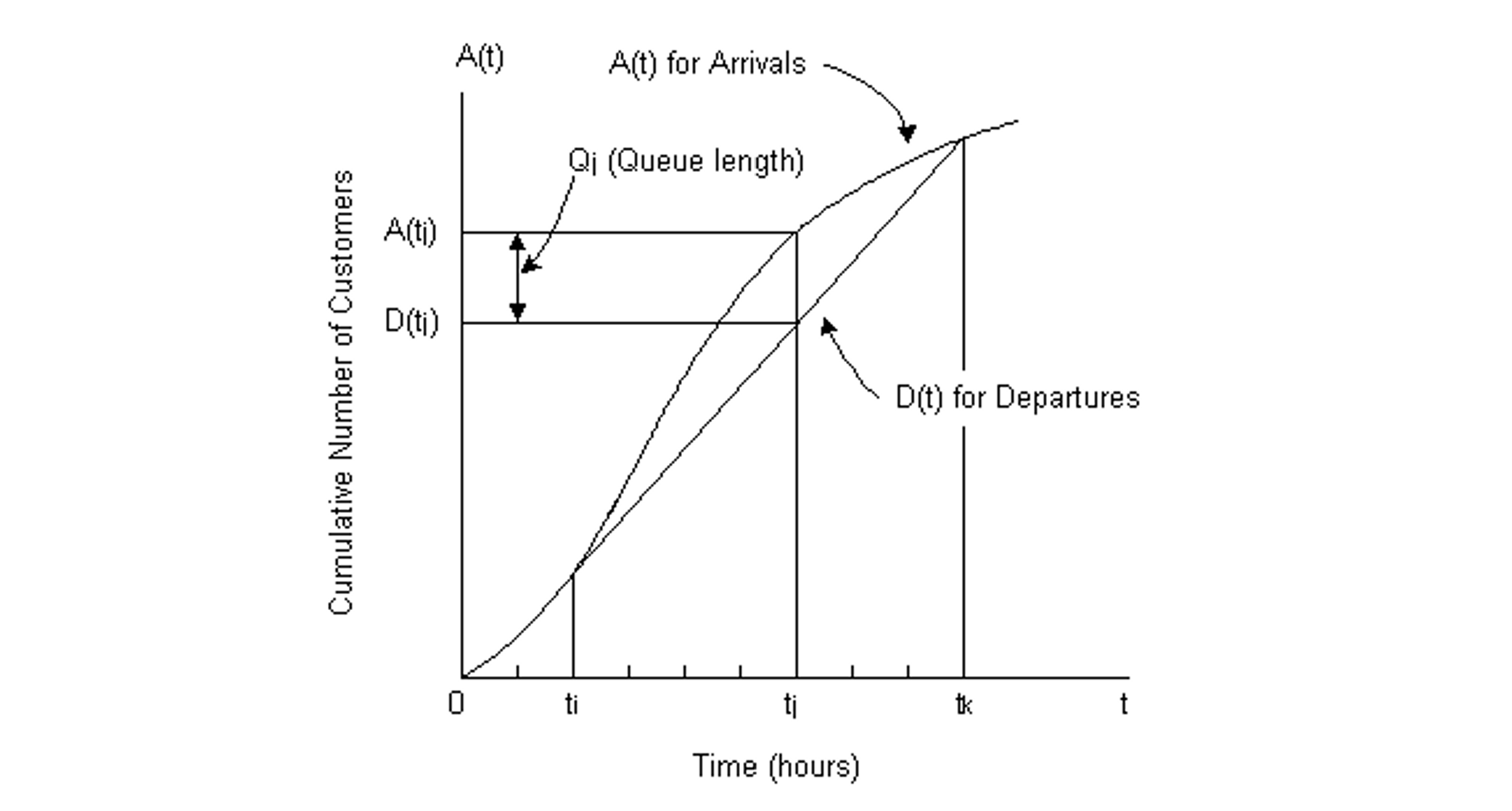

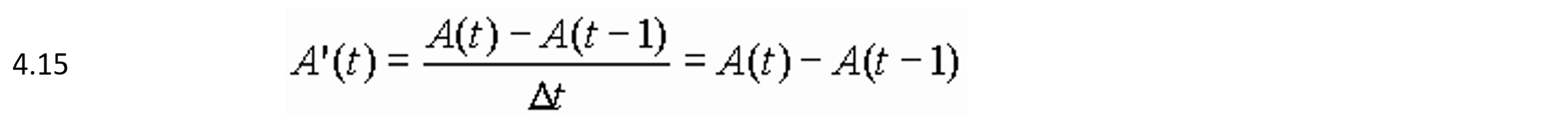

Let T be the time for the delivery of a particular item, R be the time required to process the order, and S be the shipping time. Then, the minimum amount of time for the delivery of the item is T = R + S. In general, both R and S are random variables; hence T is also a random variable. For the sake of simplicity, we shall consider only the case of instant processing for an order, i.e. R = 0. Then, the delivery time T equals the shipping time S.

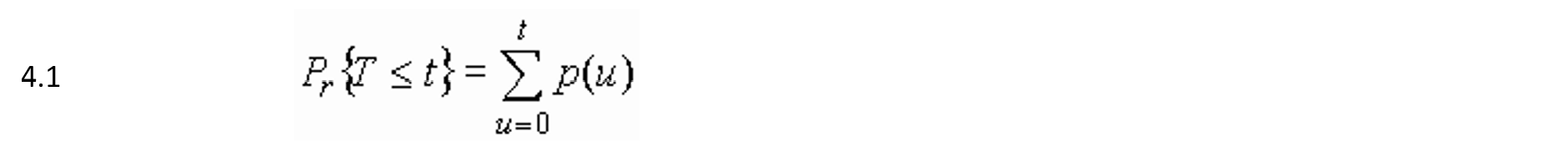

Since T is a random variable, the chance that an item will be delivered on day t is represented by the probability p(t). Then, the probability that the item will be delivered on or before t day is given by:

If a and b are the lower and upper bounds of possible delivery dates, the expected delivery time is then given by:

The lead time L for ordering an item is the time-period ahead of the delivery time, and it will depend on the trade-off between holding costs and unavailability costs. A project manager may want to avoid the unavailable cost by requiring delivery on or before the scheduled date-of-use, or they may be able to lower the holding cost by adopting a more flexible lead time based on the expected delivery time. For example, the manager may make the trade-off by specifying the lead time to be D days more than the expected delivery time, i.e.,

where D may vary from 0 to the number of additional days required to produce certain delivery on the desired date.

In a more realistic situation, the project manager would also contend with the uncertainty of exactly when the item might be required. Even if the item is scheduled for use on a particular date, the work progress might vary so that the desired date would differ. In many cases, greater than expected work progress may result in no savings because materials for future activities are unavailable.

Example 4-7: Lead time for ordering with no processing time.

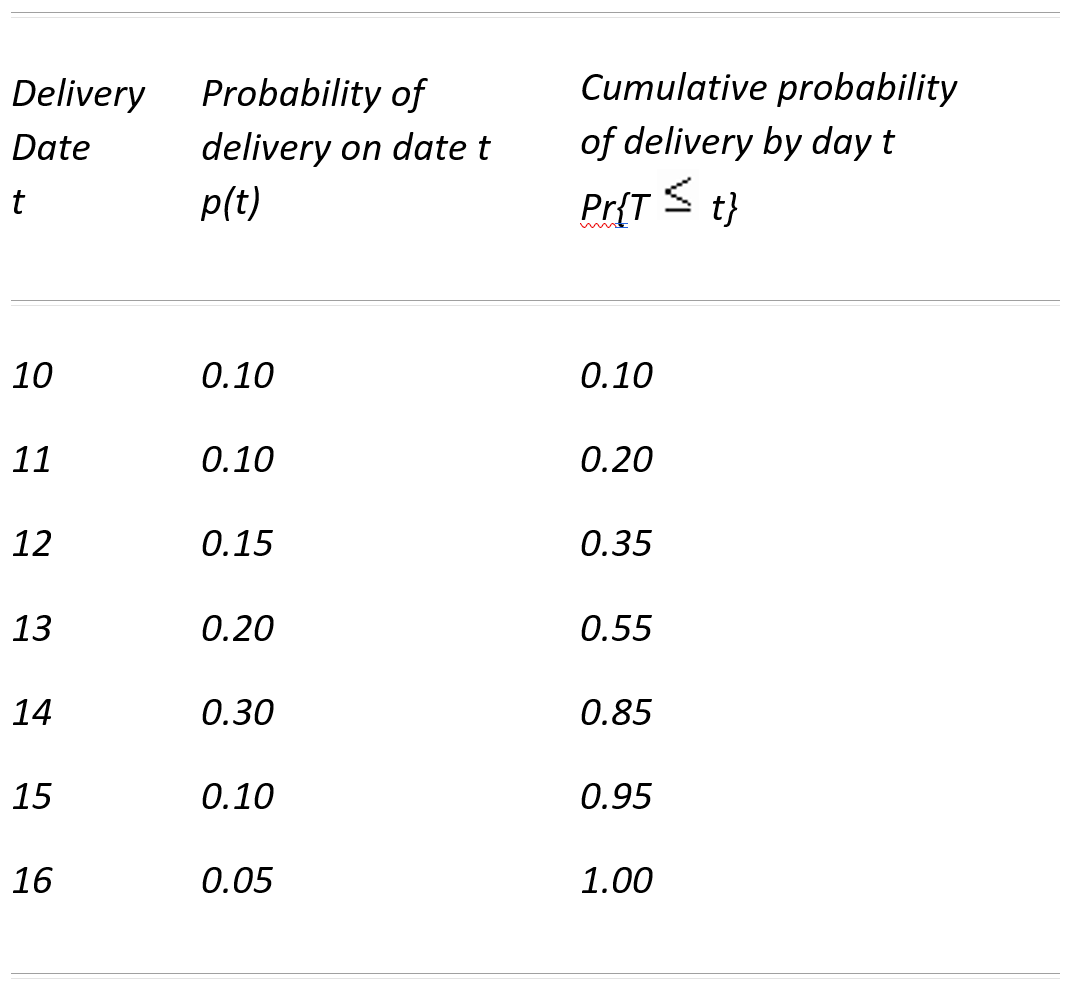

Table 4-1 summarizes the probability of different delivery times for an item. In this table, the first column lists the possible shipping times (ranging from 10 to 16 days), the second column lists the probability or chance that this shipping time will occur, and the third column summarizes the chance that the item arrives on or before a particular date. This table can be used to indicate the chance that the item will arrive on a desired date for different lead times. For example, if the order is placed 12 days in advance of the desired date (so the lead time is 12 days), then there is a 15% chance that the item will arrive exactly on the desired day and a 35% chance that the item will arrive on or before the desired date. Note that this implies that there is a 1 – 0.35 = 0.65 or 65% chance that the item will not arrive by the desired date with a lead time of 12 days. Given the information in Table 4-1, when should the item order be placed?

Table 4-1 Delivery Date on Orders and Probability of Delivery for an Example

Suppose that the scheduled date of use for the item is in 16 days. To be completely certain to have delivery by the desired day, the order should be placed 16 days in advance. However, the expected delivery date with a 16-day lead time would be:

= (10)(0.1) + (11)(0.1) + (12)(0.15) + (13)(0.20) + (14)(0.30) + (15)(0.10) + (16)(0.05) = 13.0

Thus, the actual delivery date may be 16-13 = 3 days early, and this early delivery might involve significant holding costs. A project manager might then decide to provide a lead time so that the expected delivery date was equal to the desired assembly date as long as the availability of the item was not critical. Alternatively, the project manager might negotiate a more certain delivery date from the supplier.

4.10 Construction Equipment

The selection of the appropriate type and size of construction equipment often affects the required amount of time and effort and thus the job-site productivity of a project. It is therefore important for site managers and construction planners to be familiar with the characteristics of the major types of equipment most commonly used in construction. [9] An introduction is made here. For a more in-depth and up-to-date text on this subject read Construction Planning, Equipment, and Methods, 10th Edition by the late Robert L. Peurifoy, Clifford J. Schexnayder, Aviad Shapira, Robert L. Schmitt, Aaron Cohen, ISBN: 9781264278725, Publication Date & Copyright: 2024 McGraw Hill.

Excavation and Loading

Excavators are used to remove soil and broken or crushed rock and load those materials in haul vehicles. Excavators can be wheeled or tracked, and they can have various attachments mounted on them including shovels, hydraulic sheers, clam-shell loaders and other devices.

Figure 4-3 Tracked back-hoes with various attachments (MGI Construction Corp | When the stars line up | flicker)

Figure 4-4 Haul vehicles being loaded with dozer assistance (Washington State Dept of Transportation | Wilburton Work August 10, 2008| flickr)

A tractor consists of a crawler mounting and a non-revolving cab. When an earth moving blade is attached to the front end of a tractor, the assembly is called a bulldozer. When a bucket is attached to its front end, the assembly is known as a loader or bucket loader. There are different types of loaders designed to handle most efficiently materials of different weights and moisture contents.

Figure 4-5 A dozer (Eric.Ray | Dozer | flickr)

Scrapers are multiple-units of tractor-truck and blade-bucket assemblies with various combinations to facilitate the loading and hauling of earthwork. Major types of scrapers include single engine two-axle or three axle scrapers, twin-engine all-wheel-drive scrapers, elevating scrapers, and push-pull scrapers. Each type has different characteristics of rolling resistance, maneuverability stability, and speed in operation. Scrapers make the most sense economically for medium haul distances. For longer distances, separating the excavation and haul functions makes more sense, as both types of equipment can be kept busy with a balanced equipment spread.

Figure 4-6 A scraper (Bill Jacobus | CAT Scraper| flickr)

Compaction and Grading

The function of compaction equipment is to produce higher density in soil mechanically. The basic forces used in compaction are static weight, kneading, impact and vibration. The degree of compaction that may be achieved depends on the properties of soil, its moisture content, the thickness of the soil layer for compaction and the method of compaction. Typical compaction equipment is shown in Figure 4-7, which includes rollers with different operating characteristics.

Figure 4-7 Compactors (Hawaii County | Compactor | flickr)

The function of grading equipment (Figure 4-8) is to bring the earthwork to the desired shape and elevation. Major types of grading equipment include motor graders and grade trimmers. The former is an all-purpose machine for grading and surface finishing, while the latter is used for heavy construction because of its higher operating speed.

Figure 4-8 A grader (Bill Jacobus | CAT Grader| flickr)

Drilling and Blasting

Rock excavation is an audacious task requiring special equipment and methods. The degree of difficulty depends on physical characteristics of the rock type to be excavated, such as grain size, planes of weakness, weathering, brittleness and hardness. The task of rock excavation includes loosening, loading, hauling and compacting. The loosening operation is specialized for rock excavation and is performed by drilling, blasting or ripping.

Major types of drilling equipment are percussion drills, rotary drills, and rotary-percussion drills. A percussion drill penetrates and cuts rock by impact while it rotates without cutting on the upstroke. Common types of percussion drills include a jackhammer which is hand-held and others which are mounted on a fixed frame or on a wagon or crawl for mobility. A rotary drill cuts by turning a bit against the rock surface. A rotary-percussion drill combines the two cutting movements to provide a faster penetration in rock.

Blasting requires the use of explosives, the most common of which is dynamite. Generally, electric blasting caps are connected in a circuit with insulated wires. Power sources may be power lines or blasting machines designed for firing electric cap circuits. Also available are non-electrical blasting systems which combine the precise timing and flexibility of electric blasting and the safety of non-electrical detonation.

Tractor-mounted rippers are capable of penetrating and prying loose most rock types. The blade or ripper is connected to an adjustable shank which controls the angle at the tip of the blade as it is raised or lowered. Automated ripper control may be installed to control ripping depth and tip angle.

In rock tunneling, special tunnel machines equipped with multiple cutter heads and capable of excavating full diameter of the tunnel are now available. Their use has increasingly replaced the traditional methods of drilling and blasting.

Lifting and Erecting

Derricks are commonly used to lift equipment of materials in industrial or building construction. A derrick consists of a vertical mast and an inclined boom sprouting from the foot of the mast. The mast is held in position by guys or stifflegs connected to a base while a topping lift links the top of the mast and the top of the inclined boom. A hook in the road line hanging from the top of the inclined boom is used to lift loads. Guy derricks may easily be moved from one floor to the next in a building under construction while stiffleg derricks may be mounted on tracks for movement within a work area.

Tower cranes are used to lift loads to great heights and to facilitate the erection of steel building frames. Horizon boom type tower cranes are most common in high-rise building construction. Inclined boom type tower cranes are also used for erecting steel structures. Prismatic boom cranes are expensive to rent, mobile, and are often used to erect and dismantle tower cranes which remain on site often for the duration of a project (Figure 4-9).

Figure 4-9 Tower crane being erected with prismatic boom crane (Les Chatfield | Raise the Jib | flickr)

Mixing and Paving

Basic types of equipment for paving include machines for dispensing Portland cement concrete and asphalt concrete paving materials for pavement surfaces. Concrete mixers may also be used to mix portland cement, sand, gravel and water in batches for other types of construction other than paving.

A truck mixer refers to a concrete mixer mounted on a truck which is capable of transporting ready-mixed concrete from a central batch plant to construction sites. A paving mixer is a self-propelled concrete mixer equipped with a boom and a bucket to place concrete at any desired point within a roadway. It can be used as a stationary mixer or used to supply slipform pavers that are capable of spreading, consolidating and finishing a concrete slab without the use of forms.

Construction Tools and Other Equipment

Air compressors and pumps are widely used as the power sources for construction tools and equipment. Common pneumatic construction tools include drills, hammers, grinders, saws, wrenches, staple guns, sandblasting guns, and concrete vibrators. Pumps are used to supply water or to dewater at construction sites and to provide water jets for some types of construction.

Automation of Equipment and Construction Robotics

The introduction of new mechanized equipment in construction has had a profound effect on the cost and productivity of construction as well as the methods used for construction itself. An exciting example of innovation in this regard is the introduction of computer microprocessors on tools and equipment. As a result, the performance and activity of equipment can be continually monitored and adjusted for improvement. In many cases, automation of at least part of the construction process is possible and desirable. For example, wrenches that automatically monitor the elongation of bolts and the applied torque can be programmed to achieve the best bolt tightness. On grading projects, laser-controlled scrapers can produce desired cuts faster and more precisely than wholly manual methods. [10]

As early as 2002, publications were indicating up to 50% productivity improvement by controlling earth moving with GPS receivers, 3D cut-and-fill designs, isometric operator perspectives of current progress, and sometimes robotic blade control (“Factors in Productivity and Unit Cost for Advanced Machine Guidance,” by Snaebjorn Jonasson, Phillip S. Dunston, Kamal Ahmed, and Jeff Hamilton, ASCE Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, Volume 128, Issue 5 https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2002)128:5(367) ) These “stakeless” systems have been applied to most kinds of excavation and earth moving equipment by the major construction equipment manufacturers and are sometimes available as add-ons. Autonomous haul vehicles have been operational at mining sites for decades. Construction robotics is experiencing a renaissance in the 2020’s. A good open-source store of information on this subject can be found via the web site of the International Association for Automation and Robotics in Construction https://www.iaarc.org/ .

Example 4-8: Tunneling Equipment [11]

In the mid-1980’s, some Japanese firms were successful in obtaining construction contracts for tunneling in the United States by using new equipment and methods. For example, the Japanese firm of Obayashi won the sewer contract in San Francisco because of its advanced tunneling technology. When a tunnel is dug through soft earth, as in San Francisco, it must be maintained at a few atmospheres of pressure to keep it from caving in. Workers must spend several hours in a pressure chamber before entering the tunnel and several more in decompression afterwards. They can stay inside for only three or four hours, always at considerable risk from cave-ins and asphyxiation. Obayashi used the new Japanese “earth-pressure-balance” method, which eliminates these problems. Whirling blades advance slowly, cutting the tunnel. The loose earth temporarily remains behind to balance the pressure of the compact earth on all sides. Meanwhile, prefabricated concrete segments are inserted and joined with waterproof seals to line the tunnel. Then the loose earth is conveyed away. This new tunneling method enabled Obayashi to bid $5 million below the engineer’s estimate for a San Francisco sewer. The firm completed the tunnel three months ahead of schedule. In effect, an innovation involving new technology and methods led to considerable cost and time savings.

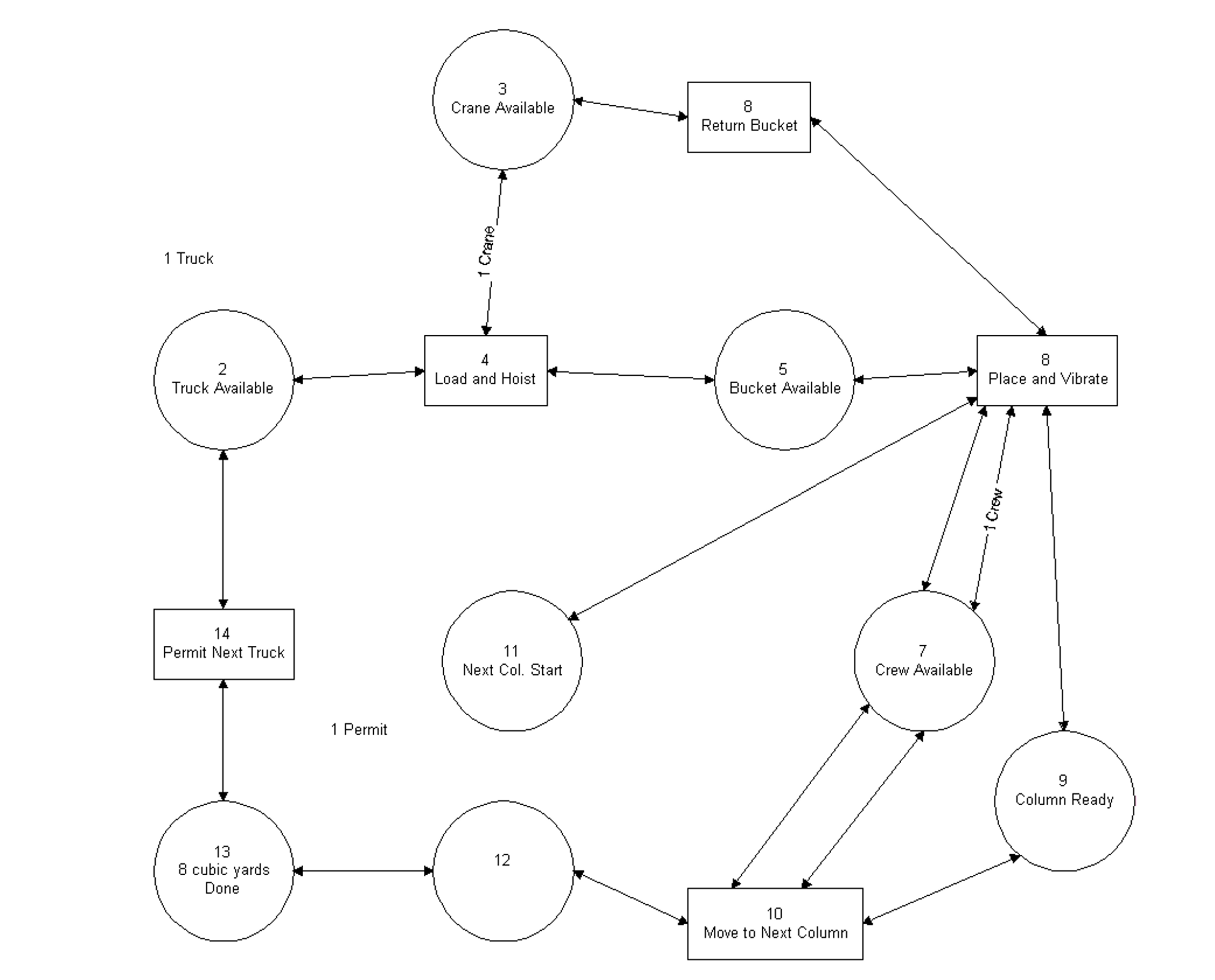

4.11 Choice of Equipment and Standard Production Rates

Typically, construction equipment is used to perform essentially repetitive operations, and can be broadly classified according to two basic functions: (1) equipment such as cranes, graders, etc. which stay within the confines of the construction site, and (2) equipment such as dump trucks, ready mixed concrete trucks, flat-bed trucks, etc. which transport materials to and from the site. In both cases, the cycle of a piece of equipment is a sequence of tasks which is repeated to produce units of output. For example, the sequence of tasks for a crane might be to fit and install a wall panel (or a package of eight wall panels) on the side of a building; similarly, the sequence of tasks of a ready mixed concrete truck might be to receive, haul and unload two cubic yards (or one truck load) of fresh concrete.

To increase job-site productivity, it is beneficial to select equipment with proper characteristics and a size most suitable for the work conditions at a construction site. In excavation for building construction, for example, factors that could affect the selection of excavators include:

- Size of the job: Larger volumes of excavation will require larger excavators, or smaller excavators in greater number.

- Activity time constraints: Shortage of time for excavation may force contractors to increase the size or numbers of equipment for activities related to excavation.

- Availability of equipment: Productivity of excavation activities will diminish if the equipment used to perform them is available but not the most appropriate.

- Cost of transportation of equipment: This cost depends on the size of the job, the distance of transportation, and the means of transportation.

- Type of excavation: Principal types of excavation in building projects are cut and/or fill, excavation massive, and excavation for the elements of foundation. The most adequate equipment to perform one of these activities is not the most adequate to perform the others.

- Soil characteristics: The type and condition of the soil is important when choosing the most adequate equipment since each piece of equipment has different outputs for different soils. Moreover, one excavation pit could have different soils at different stratums.

- Geometric characteristics of elements to be excavated: Functional characteristics of different types of equipment makes such considerations necessary.

- Space constraints: The performance of equipment is influenced by the spatial limitations for the movement of excavators.

- Characteristics of haul units: The size of an excavator will depend on the haul units if there is a constraint on the size and/or number of these units.

- Location of dumping areas: The distance between the construction site and dumping areas could be relevant not only for selecting the type and number of haulers, but also the type of excavators.

- Weather and temperature: Rain, snow and severe temperature conditions affect the job-site productivity of labor and equipment.

By comparing various types of machines for excavation, for example, power shovels (or “front-end loaders”) are generally found to be the most suitable for excavating from a level surface and for attacking an existing digging surface or one created by the power shovel; furthermore, they have the capability of placing the excavated material directly onto the haulers. Another alternative is to use bulldozers for excavation in relatively flat terrain and back-hoes or front-end loaders to transfer the materials to haulers.

The choice of the type and size of haulers is based on the consideration that the number of haulers selected must be capable of disposing of the excavated materials expeditiously, while minimizing idle time for all of the equipment involved. Factors which affect this selection include:

- Output of excavators: The size and characteristics of the excavators selected will determine the output volume excavated per day.

- Distance to dump site: Sometimes part of the excavated materials may be piled up at the job-site for use as backfill.

- Probable average speed: The average speed of the haulers to and from the dumping site will determine the cycle time for each hauling trip.

- Volume of excavated materials: The volume of excavated materials including the part to be piled up should be hauled away as soon as possible.

- Spatial and weight constraints: The size and weight of the haulers must be feasible at the job site and over the route from the construction site to the dumping area.

Dump trucks are usually used as haulers for excavated materials as they can move freely with relatively high speeds on city streets as well as on highways.

The cycle capacity C of a piece of equipment is defined as the number of output units per cycle of operation under standard work conditions. The capacity is a function of the output units used in the measurement as well as the size of the equipment and the material to be processed. The cycle time T refers to units of time per cycle of operation. The standard production rate R of a piece of construction equipment is defined as the number of output units per unit time. Hence:

or

or

The daily standard production rate Pe of an excavator can be obtained by multiplying its standard production rate Re by the number of operating hours He per day. Thus:

where Ce and Te are cycle capacity (in units of volume) and cycle time (in hours) of the excavator respectively.

In determining the daily standard production rate of a hauler, it is necessary to determine first the cycle time from the distance D to a dump site and the average speed S of the hauler. Let Tt be the travel time for the round trip to the dump site, To be the loading time and Td be the dumping time. Then the travel time for the round trip is given by:

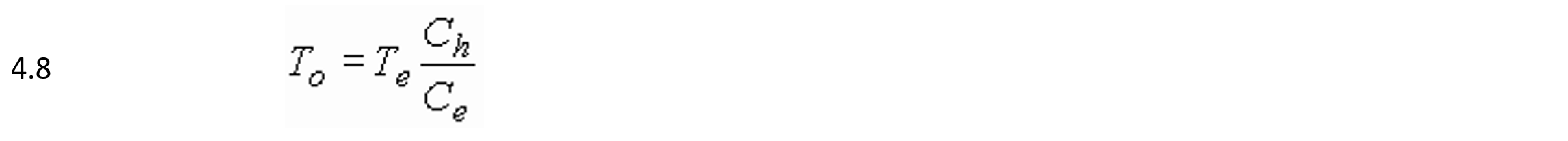

The loading time is related to the cycle time of the excavator Te and the relative capacities Ch and Ce of the hauler and the excavator respectively. In the optimum or standard case:

For a given dumping time Td, the cycle time Th of the hauler is given by:

The daily standard production rate Ph of a hauler can be obtained by multiplying its standard production rate Rh by the number of operating hours Hh per day. Hence:

This expression assumes that haulers begin loading as soon as they return from the dump site.

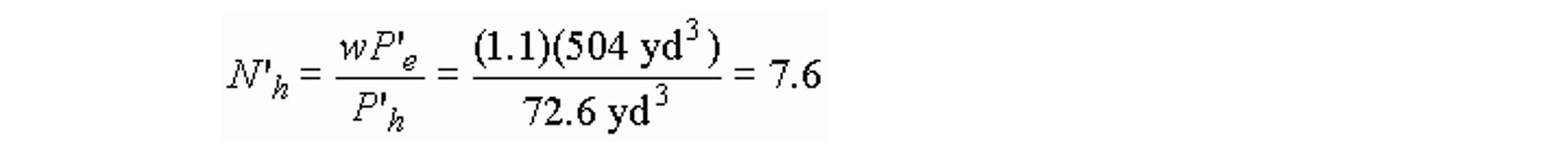

The number of haulers required is also of interest. Let w denote the swell factor of the soil such that wPe denotes the daily volume of loose excavated materials resulting from the excavation bank volume Pe. Then the approximate number of haulers required to dispose of the excavated materials is given by:

While the standard production rate of a piece of equipment is based on “standard” or ideal conditions, equipment productivities at job sites are influenced by actual work conditions and a variety of inefficiencies and work stoppages. As one example, various factor adjustments can be used to account in an approximate fashion for actual site conditions. If the conditions that lower the standard production rate are denoted by n factors F1, F2, …, Fn, each of which is smaller than 1, then the actual equipment productivity R’ at the job site can be related to the standard production rate R as follows:

On the other hand, the cycle time T’ at the job site will be increased by these factors, reflecting actual work conditions. If only these factors are involved, T’ is related to the standard cycle time T as:

Each of these various adjustment factors must be determined from experience or observation of job sites. For example, a bulk composition factor is derived for bulk excavation in building construction because the standard production rate for general bulk excavation is reduced when an excavator is used to create a ramp to reach the bottom of the bulk and to open up a space in the bulk to accommodate the hauler.

In addition to the problem of estimating the various factors, F1, F2, …, Fn, it may also be important to account for interactions among the factors and the exact influence of particular site characteristics.

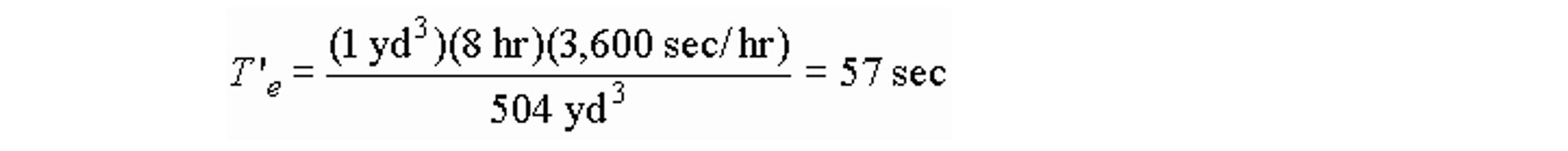

Example 4-9: Daily standard production rate of a power shovel [12]

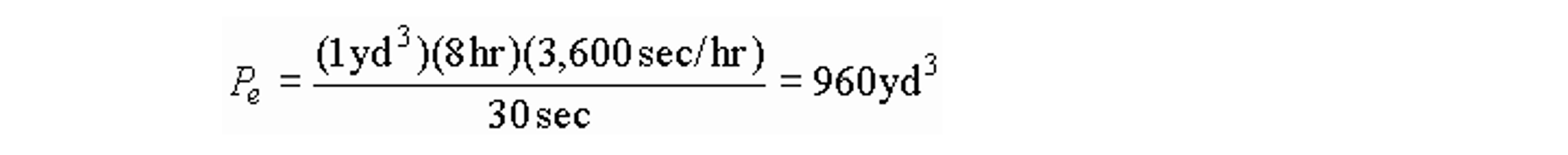

A power shovel with a bucket of one cubic yard capacity has a standard operating cycle time of 30 seconds. Find the daily standard production rate of the shovel.

For Ce = 1 cu. yd., Te = 30 sec. and He = 8 hours, the daily standard production rate is found from Eq. (4.6) as follows:

In practice, of course, this standard rate would be modified to reflect various production inefficiencies, as described in Example 4-11.

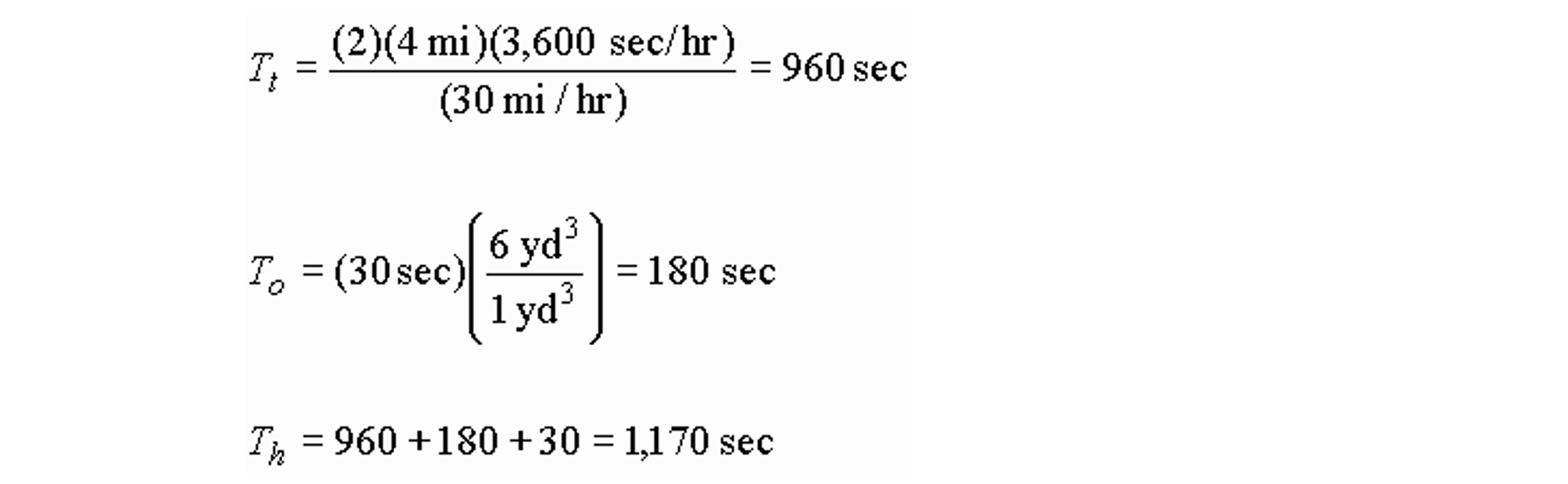

Example 4-10: Daily standard production rate of a dump truck

A dump truck with a capacity of 6 cubic yards is used to dispose of excavated materials at a dump site 4 miles away. The average speed of the dump truck is 30 mph and the dumping time is 30 seconds. Find the daily standard production rate of the truck. If a fleet of dump trucks of this capacity is used to dispose of the excavated materials in Example 4-9 for 8 hours per day, determine the number of trucks needed daily, assuming a swell factor of 1.1 for the soil.

The daily standard production rate of a dump truck can be obtained by using Equations (4.7) through (4.10):

Hence, the daily hauler productivity is:

Finally, from Equation (4.12), the number of trucks required is:

implying that 8 trucks should be used.

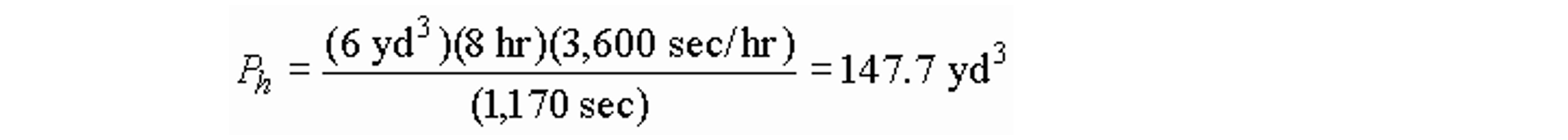

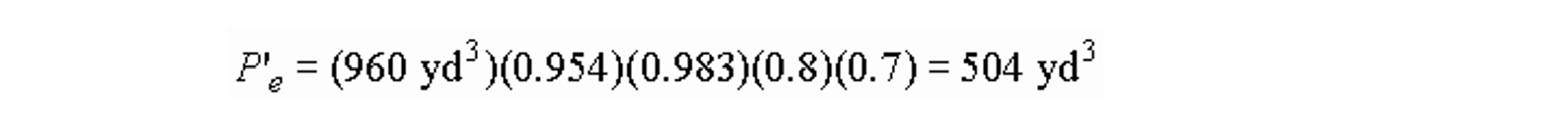

Example 4-11: Job site productivity of a power shovel

A power shovel with a bucket of one cubic yard capacity (in Example 4-9) has a standard production rate of 960 cubic yards for an 8-hour day. Determine the job site productivity and the actual cycle time of this shovel under the work conditions at the site that affects its productivity as shown below:

|

Work Conditions at the Site |

|

Factors |

|

Bulk composition |

0.954 |

|

|

Soil properties and water content |

0.983 |

|

|

Equipment idle time for worker breaks |

0.8 |

|

|

Management efficiency |

0.7 |

Using Equation (4.11), the job site productivity of the power shovel per day is given by:

The actual cycle time can be determined as follows:

Noting Equation (4.6), the actual cycle time can also be obtained from the relation T’e = (CeHe)/P’e. Thus:

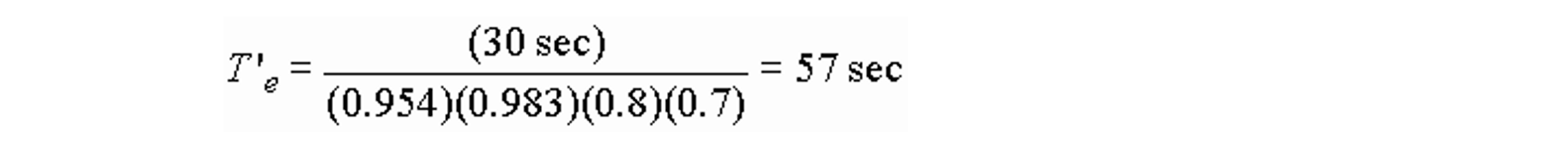

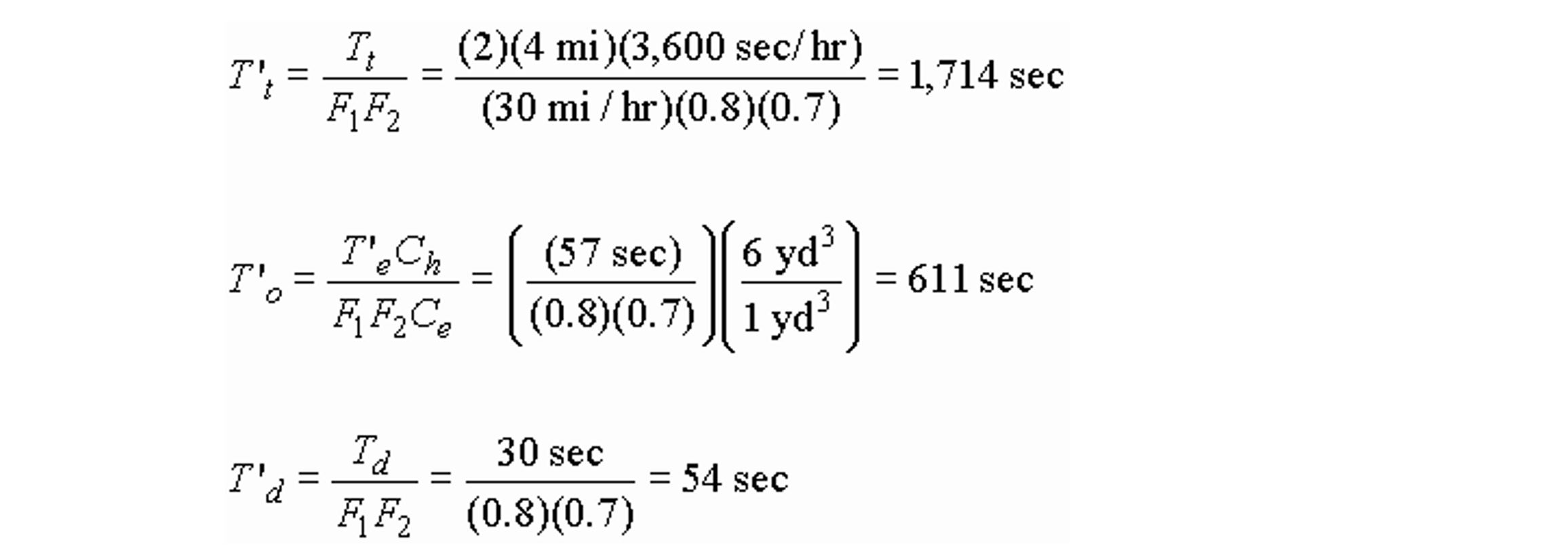

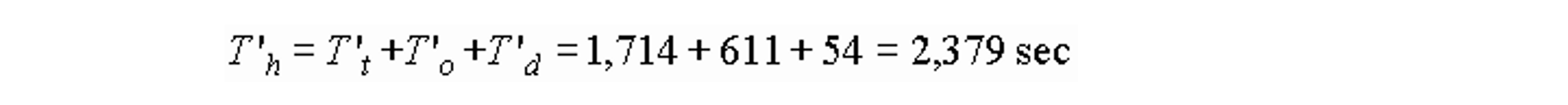

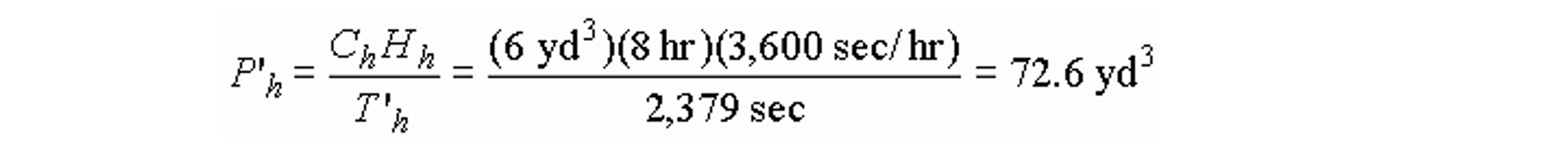

Example 4-12: Job site productivity of a dump truck

A dump truck with a capacity of 6 cubic yards (in Example 4-10) is used to dispose of excavated materials. The distance from the dump site is 4 miles and the average speed of the dump truck is 30 mph. The job site productivity of the power shovel per day (in Example 4-11) is 504 cubic yards, which will be modified by a swell factor of 1.1. The only factors affecting the job site productivity of the dump truck in addition to those affecting the power shovel are 0.80 for equipment idle time and 0.70 for management efficiency. Determine the job site productivity of the dump truck. If a fleet of such trucks is used to haul the excavated material, find the number of trucks needed daily.

The actual cycle time T’h of the dump truck can be obtained by summing the actual times for traveling, loading and dumping:

Hence, the actual cycle time is:

The jobsite productivity P’h of the dump truck per day is:

The number of trucks needed daily is:

so 8 trucks are required.

For additional information on equipment choice and production, many reference books and software packages exist. Common starting points are:

- Construction Planning, Equipment, and Methods, 10th Edition by the late Robert L. Peurifoy, Clifford J. Schexnayder, Aviad Shapira, Robert L. Schmitt, Aaron Cohen, ISBN: 9781264278725, Publication Date & Copyright: 2024 McGraw Hill.

- Caterpillar Performance Handbook, Edition 49 (or latest edition), Caterpillar Inc., Peoria, Illinois, 2019, downloadable for free from several websites, including https://www.macallister.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/caterpillar-performance-handbook-49.pdf