8 Construction Pricing and Contracting

8.1 Pricing for Constructed Facilities

Because of the unique nature of constructed facilities, it is almost imperative to have a separate price for each facility. The construction contract price includes the direct project cost including field supervision expenses plus the markup imposed by contractors for general overhead expenses and profit. The factors influencing a facility price will vary by type of facility and location as well. Within each of the major categories of construction such as residential housing, commercial buildings, industrial complexes and infrastructure, there are smaller segments which have very different environments with regard to price setting. However, all pricing arrangements have some common features in the form of the legal documents binding the owner and the supplier(s) of the facility. Without addressing special issues in various industry segments, the most common types of pricing arrangements can be described broadly to illustrate the basic principles.

Competitive Bidding

The basic structure of the bidding process consists of the formulation of detailed plans and specifications of a facility based on the objectives and requirements of the owner, and the invitation of qualified contractors to bid for the right to execute the project. The definition of a qualified contractor usually calls for a minimal evidence of previous experience and financial stability. In the private sector, the owner has considerable latitude in selecting the bidders, ranging from open competition to the restriction of bidders to a few favored contractors. In the public sector, the rules are carefully delineated to place all qualified contractors on an equal footing for competition, and strictly enforced to prevent collusion among contractors and unethical or illegal actions by public officials.

Detailed plans and specifications are usually prepared by an architectural/engineering firm which oversees the bidding process on behalf of the owner. The final bids are normally submitted on either a lump sum or unit price basis, as stipulated by the owner. A lump sum bid represents the total price for which a contractor offers to complete a facility according to the detailed plans and specifications. Unit price bidding is used in projects for which the quantity of materials or the amount of labor involved in some key tasks is particularly uncertain. In such cases, the contractor is permitted to submit a list of unit prices for those tasks, and the final price used to determine the lowest bidder is based on the lump sum price computed by multiplying the quoted unit price for each specified task by the corresponding quantity in the owner’s estimates for quantities. However, the total payment to the winning contractor will be based on the actual quantities multiplied by the respective quoted unit prices.

Negotiated Contracts

Instead of inviting competitive bidding, private owners often choose to award construction contracts with one or more selected contractors. A major reason for using negotiated contracts is the flexibility of this type of pricing arrangement, particularly for projects of large size and great complexity or for projects which substantially duplicate previous facilities sponsored by the owner. An owner may value the expertise and integrity of a particular contractor who has a good reputation or has worked successfully for the owner in the past. If it becomes necessary to meet a deadline for completion of the project, the construction of a project may proceed without waiting for the completion of the detailed plans and specifications with a contractor that the owner can trust. However, the owner’s staff must be highly knowledgeable and competent in evaluating contractor proposals and monitoring subsequent performance.

Generally, negotiated contracts require the reimbursement of direct project cost plus the contractor’s fee as determined by one of the following methods:

- Cost plus fixed percentage

- Cost plus fixed fee

- Cost plus variable fee

- Target estimate

- Guaranteed maximum price or cost

The fixed percentage or fixed fee is determined at the outset of the project, while variable fee and target estimates are used as an incentive to reduce costs by sharing any cost savings. A guaranteed maximum cost arrangement imposes a penalty on a contractor for cost overruns and failure to complete the project on time. With a guaranteed maximum price contract, amounts below the maximum are typically shared between the owner and the contractor, while the contractor is responsible for costs above the maximum.

Speculative Residential Construction

In residential construction, developers often build houses and condominiums in anticipation of the demand of home buyers. Because the basic needs of home buyers are very similar and home designs can be standardized to some degree, the probability of finding buyers of good housing units within a relatively short time is quite high. Consequently, developers are willing to undertake speculative building, and lending institutions are also willing to finance such construction. The developer essentially sets the price for each housing unit as the market will bear and can adjust the prices of remaining units at any given time according to the market trend.

Force-Account Construction

Some owners use in-house labor forces to perform a substantial amount of construction, particularly for addition, renovation and repair work. Then, the total of the force-account charges including in-house overhead expenses will be the pricing arrangement for the construction. Examples of where this still occurs include maintenance and renovation work on large university campuses, although the long term trend continues to be toward outsourcing.

8.2 Contract Provisions for Risk Allocation

Provisions for the allocation of risk among parties to a contract can appear in numerous areas in addition to the total construction price. Typically, these provisions assign responsibility for covering the costs of possible or unforeseen occurrences. A partial list of responsibilities with concomitant risk that can be assigned to different parties would include:

- Force majeure (i.e., this provision absolves an owner or a contractor for payment for costs due to “Acts of God” and other external events such as war or labor strikes)

- Indemnification (i.e., this provision absolves the indemnified party from any payment for losses and damages incurred by a third party such as adjacent property owners.)

- Liens (i.e., assurances that third party claims are settled such as “mechanics liens” for worker wages),

- Labor laws (i.e., payments for any violation of labor laws and regulations on the job site),

- Differing site conditions (i.e., responsibility for extra costs due to unexpected site conditions),

- Delays and extensions of time,

- Liquidated damages (i.e., payments for any facility defects with payment amounts agreed to in advance)

- Consequential damages (i.e., payments for actual damage costs assessed upon impact of facility defects),

- Occupational safety and health of workers,

- Permits, licenses, laws, and regulations,

- Equal employment opportunity regulations,

- Termination for default by contractor,

- Suspension of work,

- Warranties and guarantees.

The language used for specifying the risk assignments in these areas must conform to legal requirements and past interpretations which vary in different jurisdictions or over time. Without using standard legal language, contract provisions may be unenforceable. Unfortunately, standard legal language for this purpose may be difficult to understand. As a result, project managers often have difficulty in interpreting their particular responsibilities. Competent legal counsel is required to advise the different parties to an agreement about their respective responsibilities.

Standard forms for contracts can be obtained from numerous sources, such as the American Institute of Architects (AIA) or the Associated General Contractors (AGC). These standard forms may include risk and responsibility allocations which are unacceptable to one or more of the contracting parties. In particular, standard forms may be biased to reduce the risk and responsibility of the originating organization or group. Parties to a contract should read and review all contract documents carefully. Despite the nominal contract type, the devil is always in the details.

The three examples appearing below illustrate contract language resulting in different risk assignments between a contractor (CONTRACTOR) and an owner (COMPANY). Each contract provision allocates different levels of indemnification risk to the contractor. [1]

Example 8-1: A Contract Provision Example with High Contractor Risk

“Except where the sole negligence of COMPANY is involved or alleged, CONTRACTOR shall indemnify and hold harmless COMPANY, its officers, agents and employees, from and against any and all loss, damage, and liability and from any and all claims for damages on account of or by reason of bodily injury, including death, not limited to the employees of CONTRACTOR, COMPANY, and of any subcontractor or CONTRACTOR, and from and against any and all damages to property, including property of COMPANY and third parties, direct and/or consequential, caused by or arising out of, in while or in part, or claimed to have been caused by or to have arisen out of, in whole or in part, an act of omission of CONTRACTOR or its agents, employees, vendors, or subcontractors, of their employees or agents in connection with the performance of the Contract Documents, whether or not insured against; and CONTRACTOR shall, at its own cost and expense, defend any claim, suit, action or proceeding, whether groundless or not, which may be commenced against COMPANY by reason thereof or in connection therewith, and CONTRACTOR shall pay any and all judgments which may be recovered in such action, claim, proceeding or suit, and defray any and all expenses, including costs and attorney’s fees which may be incurred by reason of such actions, claims, proceedings, or suits.”

Comment: This is a very burdensome provision for the contractor. It makes the contractor responsible for practically every conceivable occurrence and type of damage, except when a claim for loss or damages is due to the sole negligence of the owner. As a practical matter, sole negligence on a construction project is very difficult to ascertain because the work is so inter-twined. Since there is no dollar limitation to the contractor’s exposure, sufficient liability coverage to cover worst scenario risks will be difficult to obtain. The best the contractor can do is to obtain as complete and broad excess liability insurance coverage as can be purchased. This insurance is costly, so the contractor should insure the contract price is sufficiently high to cover the expense.

Example 8-2: An Example Contract Provision with Medium Risk Allocation to Contractor

“CONTRACTOR shall protect, defend, hold harmless, and indemnify COMPANY from and against any loss, damage, claim, action, liability, or demand whatsoever (including, with limitation, costs, expenses, and attorney’s fees, whether for appeals or otherwise, in connection therewith), arising out of any personal injury (including, without limitation, injury to any employee of COMPANY, CONTRACTOR or any subcontractor), arising out of any personal injury (including, without limitation, injury to any employee of COMPANY, CONTRACTOR, or any subcontractor), including death resulting therefrom or out of any damage to or loss or destruction of property, real and or personal (including property of COMPANY, CONTRACTOR, and any subcontractor, and including tools and equipment whether owned, rented, or used by CONTRACTOR, any subcontractor, or any workman) in any manner based upon, occasioned by , or attributable or related to the performance, whether by the CONTRACTOR or any subcontractor, of the Work or any part thereof, and CONTRACTOR shall at its own expense defend any and all actions based thereon, except where said personal injury or property damage is caused by the negligence of COMPANY or COMPANY’S employees. Any loss, damage, cost expense or attorney’s fees incurred by COMPANY in connection with the foregoing may, in addition to other remedies, be deducted from CONTRACTOR’S compensation, then due or thereafter to become due. COMPANY shall effect for the benefit of CONTRACTOR a waiver of subrogation on the existing facilities, including consequential damages such as, but not by way of limitation, loss of profit and loss of product or plant downtime but excluding any deductibles which shall exist as at the date of this CONTRACT; provided, however, that said waiver of subrogation shall be expanded to include all said deductible amounts on the acceptance of the Work by COMPANY.”

Comment: This clause provides the contractor considerable relief. He still has unlimited exposure for injury to all persons and third-party property but only to the extent caused by the contractor’s negligence. The “sole” negligence issue does not arise. Furthermore, the contractor’s liability for damages to the owner’s property – a major concern for contractors working in petrochemical complexes, at times worth billions – is limited to the owner’s insurance deductible, and the owner’s insurance carriers have no right of recourse against the contractor. The contractor’s limited exposure regarding the owner’s facilities ends on completion of the work.

Example 8-3: An Example Contract Provision with Low Risk Allocation to Contractor

“CONTRACTOR hereby agrees to indemnify and hold COMPANY and/or any parent, subsidiary, or affiliate, or COMPANY and/or officers, agents, or employees of any of them, harmless from and against any loss or liability arising directly or indirectly out of any claim or cause of action for loss or damage to property including, but not limited to, CONTRACTOR’S property and COMPANY’S property and for injuries to or death of persons including but not limited to CONTRACTOR’S employees, caused by or resulting from the performance of the work by CONTRACTOR, its employees, agents, and subcontractors and shall, at the option of COMPANY, defend COMPANY at CONTRACTOR’S sole expense in any litigation involving the same regardless of whether such work is performed by CONTRACTOR, its employees, or by its subcontractors, their employees, or all or either of them. In all instances, CONTRACTOR’S indemnity to COMPANY shall be limited to the proceeds of CONTRACTOR’S umbrella liability insurance coverage.”

Comment: With respect to indemnifying the owner, the contractor in this provision has minimal out-of-pocket risk. Exposure is limited to whatever can be collected from the contractor’s insurance company.

8.3 Risks and Incentives on Construction Quality

All owners want quality construction with reasonable costs, but not all are willing to share risks and/or provide incentives to enhance the quality of construction. Sophisticated owners recognize that they do not get the best quality of construction by squeezing the last dollar of profit from the contractor, and they accept the concept of risk sharing/risk assignment in principle in letting construction contracts. However, the implementation of such a concept over the last several decades has received mixed results.

Many public owners have been the victims of their own schemes, not only because of the usual requirement in letting contracts of public works through competitive bidding to avoid favoritism, but at times because of the sheer weight of entrenched bureaucracy. Some contractors steer away from public works altogether; others submit bids at higher prices to compensate for the restrictive provisions of contract terms. As a result, some public authorities find that either there are few responsible contractors responding to their invitations to submit bids or the bid prices far exceed their engineers’ estimates. Those public owners who have adopted the federal government’s risk sharing/risk assignment contract concepts have found that while initial bid prices may have decreased somewhat, claims and disputes on contracts are more frequent than before, and notably more so than in privately funded construction. Some of these claims and disputes can no doubt be avoided by improving the contract provisions. [2] A review of relative performance of contracting options from 2020 updates these observations (“Revisiting Project Delivery System Performance from 1998 to 2018,” by Franz, Molenaar, and Roberts, Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, Volume 146, Issue 9, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001896).

Since most claims and disputes arise most frequently from lump sum contracts for both public and private owners, the following factors associated with lump sum contracts are particularly noteworthy:

- unbalanced bids in unit prices on which periodic payment estimates are based.

- change orders subject to negotiated payments

- changes in design or construction technology

- incentives for early completion

An unbalanced bid refers to raising the unit prices on items to be completed in the early stage of the project and lowering the unit prices on items to be completed in the later stages. The purpose of this practice on the part of the contractor is to ease its burden of construction financing. It is better for owners to offer explicit incentives to aid construction financing in exchange for lower bid prices than to allow the use of hidden unbalanced bids. Unbalanced bids may also occur if a contractor feels some item of work was underestimated in amount, so that a high unit price on that item would increase profits. Since lump sum contracts are awarded on the basis of low bids, it is difficult to challenge the low bidders on the validity of their unit prices except for flagrant violations. Consequently, remedies should be sought by requesting the contractor to submit pertinent records of financial transactions to substantiate the expenditures associated with its monthly billings for payments of work completed during the period.

One of the most contentious issues in contract provisions concerns the payment for change orders. The owner and its engineer should have an appreciation of the effects of changes for specific items of work and negotiate with the contractor on the identifiable cost of such items. The owner should require the contractor to submit the price quotation within a certain period of time after the issuance of a change order and to assess whether the change order may cause delay damages. If the contract does not contain specific provisions on cost disclosures for evaluating change order costs, it will be difficult to negotiate payments for change orders and claim settlements later.

In some projects, the contract provisions may allow the contractor to provide alternative design and/or construction technology. The owner may impose different mechanisms for pricing these changes. For example, a contractor may suggest a design or construction method change that fulfills the performance requirements. Savings due to such changes may accrue to the contractor or the owner, or may be divided in some fashion between the two. The contract provisions must reflect the owner’s risk-reward objectives in calling for alternate design and/or construction technology. While innovations are often sought to save money and time, unsuccessful innovations may require additional money and time to correct earlier misjudgment. At worst, a failure could have serious consequences.

In spite of admonitions and good intentions for better planning before initiating a construction project, most owners want a facility to be in operation as soon as possible once a decision is made to proceed with its construction. Many construction contracts contain provisions of penalties for late completion beyond a specified deadline; however, unless such provisions are accompanied by similar incentives for early completion, they may be ruled unenforceable in court. Early completion may result in significant savings, particularly in rehabilitation projects in which the facility users are inconvenienced by the loss of the facility and the disruption due to construction operations.

Example 8-4: Arkansas Rice Growers Cooperative Association v. Alchemy Industries

A 1986 court case can illustrate the assumption of risk on the part of contractors and design professionals. [3] The Arkansas Rice Growers Cooperative contracted with Alchemy Industries, Inc. to provide engineering and construction services for a new facility intended to generate steam by burning rice hulls. Under the terms of the contract, Alchemy Industries guaranteed that the completed plant would be capable of “reducing a minimum of seven and one-half tons of rice hulls per hour to an ash and producing a minimum of 48 million BTU’s per hour of steam at 200 pounds pressure.” Unfortunately, the finished plant did not meet this performance standard, and the Arkansas Rice Growers Cooperative Association sued Alchemy Industries and its subcontractors for breach of warranty. Damages of almost $1.5 million were awarded to the Association.

8.4 Types of Construction Contracts

While construction contracts serve as a means of pricing construction, they also structure the allocation of risk to the various parties involved. The owner has the sole power to decide what type of contract should be used for a specific facility to be constructed and to set forth the terms in a contractual agreement. It is important to understand the risks to the contractors associated with different types of construction contracts.

Lump Sum Contract

In a lump sum contract, the owner has essentially assigned all the risk to the contractor, who in turn can be expected to ask for a higher markup in order to take care of unforeseen contingencies. Beside the fixed lump sum price, other commitments are often made by the contractor in the form of submittals such as a specific schedule, the management reporting system or a quality control program. If the actual cost of the project is underestimated, the underestimated cost will reduce the contractor’s profit by that amount. An overestimate has an opposite effect, but it may reduce the chance of being a low bidder for the project.

Unit Price Contract

In a unit price contract, the risk of inaccurate estimation of uncertain quantities for some key tasks has been removed from the contractor. However, a contractor may submit an “unbalanced bid” when it discovers large discrepancies between its estimates and the owner’s estimates of these quantities. Depending on the confidence of the contractor on its own estimates and its propensity for risk, a contractor can slightly raise the unit prices on the underestimated tasks while lowering the unit prices on other tasks. If the contractor is correct in its assessment, it can increase its profit substantially since the payment is made on the actual quantities of tasks; and if the reverse is true, it can lose on this basis. Furthermore, the owner may disqualify a contractor if the bid appears to be heavily unbalanced. To the extent that an underestimate or overestimate is caused by changes in the quantities of work, neither error will affect the contractor’s profit beyond the markup in the unit prices.

Cost Plus Fixed Percentage Contract

For certain types of construction involving new technology or extremely pressing needs, the owner is sometimes forced to assume all risks of cost overruns. The contractor will receive the actual direct job cost plus a fixed percentage and have little incentive to reduce job cost. Furthermore, if there are pressing needs to complete the project, overtime payments to workers are common and will further increase the job cost. Unless there are compelling reasons, such as the urgency in the construction of military installations, the owner should not use this type of contract.

Cost Plus Fixed Fee Contract

Under this type of contract, the contractor will receive the actual direct job cost plus a fixed fee, and it will have some incentive to complete the job quickly since its fee is fixed regardless of the duration of the project. However, the owner still assumes the risks of direct job cost overrun while the contractor may risk the erosion of its profits if the project is dragged on beyond the expected time.

Cost Plus Variable Percentage Contract

For this type of contract, the contractor agrees to a penalty if the actual cost exceeds the estimated job cost, or a reward if the actual cost is below the estimated job cost. In return for taking the risk on its own estimate, the contractor is allowed a variable percentage of the direct job-cost for its fee. Furthermore, the project duration is usually specified, and the contractor must abide by the deadline for completion. This type of contract allocates considerable risk for cost overruns to the owner, but also provides incentives to contractors to reduce costs as much as possible.

Target Estimate Contract

This is another form of contract which specifies a penalty or reward to a contractor, depending on whether the actual cost is greater than or less than the contractor’s estimated direct job cost. Usually, the percentages of savings or overrun to be shared by the owner and the contractor are predetermined and the project duration is specified in the contract. Bonuses or penalties may be stipulated for different project completion dates.

Guaranteed Maximum Cost Contract

When the project scope is well defined, an owner may choose to ask the contractor to take all the risks, both in terms of actual project cost and project time. Any work change orders from the owner must be extremely minor if at all, since performance specifications are provided to the owner at the outset of construction. The owner and the contractor agree to a project cost guaranteed by the contractor as maximum. There may be or may not be additional provisions to share any savings if any in the contract. This type of contract is particularly suitable for turnkey operation.

Partnering, Lean Project Delivery and Integrated Project Delivery

Partnering, Lean Project Delivery and Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) are contracting approaches that have achieved popularity in certain regions for certain types of projects. Typically, these projects involve some complexity, and the contract form is one that shares risk through a definition of project governance (or a shared business model) through its multiple phases in addition to some conventional contract language. In, “Comparative analysis between integrated project delivery and lean project delivery,” by Mesa, Molenaar, and Alarcón, (International Journal of Project Management 37 (3), 395-409, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2019.01.012 ) IPD and lean project delivery are explained and analyzed.

8.5 Relative Costs of Construction Contracts

Regardless of the type of construction contract selected by the owner, the contractor recognizes that the actual construction cost will never be identical to its own estimate because of imperfect information and the inability to control everything related to the project. Furthermore, it is common for the owner to place work change orders to modify the original scope of work for which the contractor will receive additional payments as stipulated in the contract. The contractor will use different markups commensurate with its market circumstances and with the risks involved in different types of contracts, leading to different contract prices at the time of bidding or negotiation. The type of contract agreed upon may also provide the contractor with greater incentives to try to reduce costs as much as possible. The contractor’s gross profit at the completion of a project is affected by the type of contract, the accuracy of its original estimate, and the nature of work change orders. The owner’s actual payment for the project is also affected by the contract and the nature of work change orders.

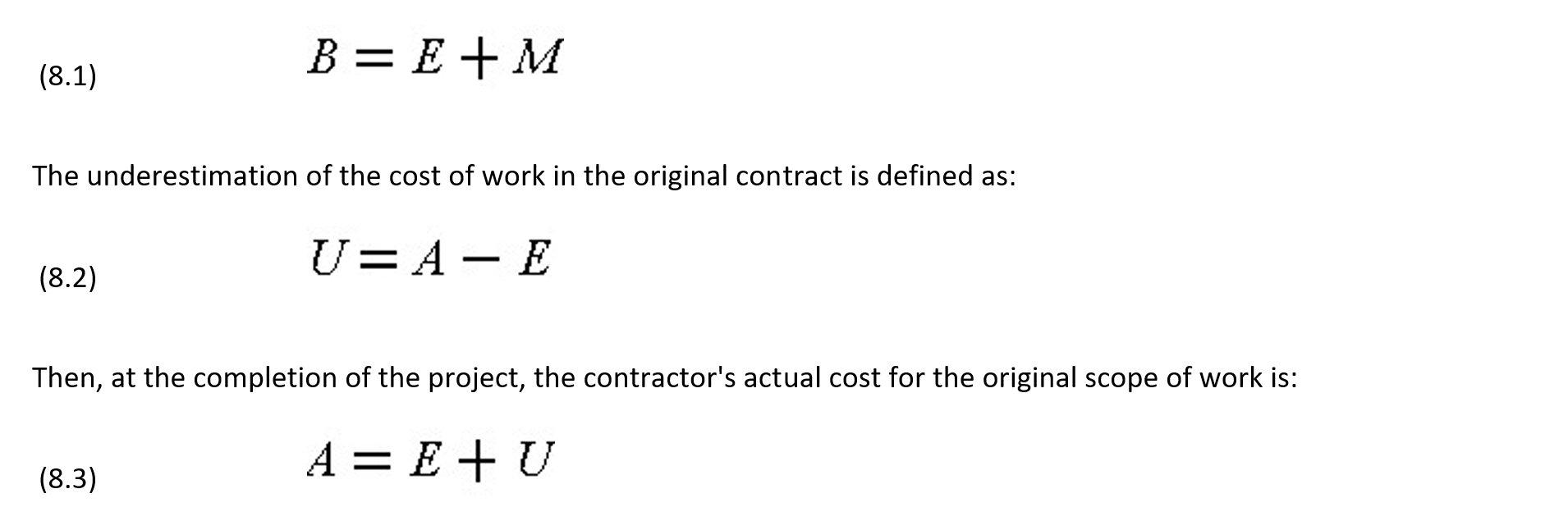

In order to illustrate the relative costs of several types of construction contracts, the pricing mechanisms for such construction contracts are formulated on the same direct job cost plus corresponding markups reflecting the risks. Let us adopt the following notation:

E = contractor’s original estimate of the direct job cost at the time of contract award

M = amount of markup by the contractor in the contract

B = estimated construction price at the time of signing contract

A = contractor’s actual cost for the original scope of work in the contract

U = underestimate of the cost of work in the original estimate (with negative value of U denoting an overestimate)

C = additional cost of work due to change orders

P = actual payment to contractor by the owner

F = contractor’s gross profit

R = basic percentage markup above the original estimate for fixed fee contract

Ri = premium percentage markup for contract type i such that the total percentage markup is (R + Ri), e.g. (R + R1) for a lump sum contract, (R + R2) for a unit price contract, and (R + R3) for a guaranteed maximum cost contract

N = a factor in the target estimate for sharing the savings in cost as agreed upon by the owner and the contractor, with 0 <= N <= 1.

At the time of a contract award, the contract price is given by:

For various types of construction contracts, the contractor’s markup and the price for construction agreed to in the contract are shown in Table 8-1. Note that at the time of contract award, it is assumed that A = E, even though the effects of underestimation on the contractor’s gross profits are different for various types of construction contracts when the actual cost of the project is assessed upon its completion.

TABLE 8-1 Original Estimated Contract Prices

| Type of Contract | Markup | Contract Price |

| 1. Lump sum 2. Unit price 3. Cost plus fixed % 4. Cost plus fixed fee 5. Cost plus variable % 6. Target estimate 7. Guaranteed max cost |

M = (R +R1)E M = (R + R2)E M = RA = RE M = RE M = R (2E – A) = RE M = RE + N (E-A) = RE M = (R + R3)E |

B = (1 + R + R1)E B = (1 + R + R2)E B = (1 + R)E B = (1 + R)E B = (1 + R)E B = (1 + R)E B = (1 + R + R3)E |

Payments of change orders are also different in contract provisions for different types of contracts. Suppose that payments for change orders agreed upon for various types of contracts are as shown in column 2 of Table 8-2. The owner’s actual payments based on these provisions as well as the incentive provisions for various types of contracts are given in column 3 of Table 8-2. The corresponding contractor’s profits under various contractual arrangements are shown in Table 8-3.

TABLE 8-2 Owner’s Actual Payment with Different Contract Provisions

| Type of Contract | Change Order Payment | Owner’s Payment |

| 1. Lump sum 2. Unit price 3. Cost plus fixed % 4. Cost plus fixed fee 5. Cost plus variable % 6. Target estimate 7. Guaranteed max cost |

C(1 + R + R1) C(1 + R + R2) C(1 + R) C C(1 + R) C 0 |

P = B + C(1 + R + R1) P = (1 + R + R2)(A + C) P = (1 + R)(A + C) P = RE + A + C P = R (2E – A + C) + A + C P = RE + N (E – A) + A + C P = B |

TABLE 8-3 Contractor’s Gross Profit with Different Contract Provisions

| Type of Contract | Profit from Change Order | Contractor’s Gross Profit |

| 1. Lump sum 2. Unit price 3. Cost plus fixed % 4. Cost plus fixed fee 5. Cost plus variable % 6. Target estimate 7. Guaranteed max cost |

C(R + R1) C(R + R2) CR 0 CR 0 -C |

F = E – A + (R + R1)(E + C) F = (R + R2)(A + C) F = R (A + C) F = RE F = R (2E – A + C) F = RE + N (E – A) F = (1 + R + R3)E – A – C |

It is important to note that the equations in Tables 8-1 through 8-3 are illustrative, subject to the simplified conditions of payments assumed under the various types of contracts. When the negotiated conditions of payment are different, the equations must also be modified.

Example 8-5: Contractor’s Gross Profits under Different Contract Arrangements

Consider a construction project for which the contractor’s original estimate is $6,000,000. For various types of contracts, R = 10%, R1 = 2%, R2 = 1%, R3 = 5% and N = 0.5. The contractor is not compensated for change orders under the guaranteed maximum cost contract if the total cost for the change orders is within 6% ($360,000) of the original estimate. Determine the contractor’s gross profit for each of the seven types of construction contracts for each of the following conditions.

(a) U = 0, C = 0

(b) U = 0, C = 6% E = $360,000

(c) U = 4% E = $240,000, C = 0

(d) U = 4% E = $240,000 C = 6% E = $360,000

(e) U = -4% E = -$240,000, C = 0

(f) U = -4% E = -$240,000, C = 6% E = $360,000

In this example, the percentage markup for the cost plus fixed percentage contract is 10% which is used as the bench mark for comparison. The percentage markup for the lump sum contract is 12% while that for the unit price contract is 11%, reflecting the degrees of higher risk. The fixed fee for the cost plus fixed fee is based on 10% of the estimated cost, which is comparable to the cost plus fixed percentage contract if there is no overestimate or underestimate in cost. The basic percentage markup is 10% for both the cost plus variable percentage contract and the target estimator contract, but they are subject to incentive bonuses and penalties that are built in the formulas for owners’ payments. The percentage markup for the guaranteed maximum cost contract is 15% to account for the high risk undertaken by the contractor. The results of computation for all seven types of contracts under different conditions of underestimation U and change order C are shown in Table 8-4.

TABLE 8-4 Contractor’s Gross Profits under Different Conditions (in $1,000)

| Type of Contract | U=0 C=0 |

U=0 C=6%E |

U=4%E C=0 |

U=4%E C=6%E |

U=-4%E C=0 |

U=-4%E C=6%E |

| 1. lump sum 2. unit price 3. cost + fixed % 4. cost + fixed fee 5. cost + Var % 6. target estimate 7. guar. max. cost |

$720 660 600 600 600 600 900 |

$763 700 636 600 636 600 540 |

$480 686 624 600 576 480 660 |

$523 726 660 600 616 480 300 |

$960 634 576 600 624 720 1,140 |

$1,003 674 612 600 660 720 780 |

Example 8-6: Owner’s Payments under Different Contract Arrangements

Using the data in Example 8-5, determine the owner’s actual payment for each of the seven types of construction contracts for the same conditions of U and C. The results of computation are shown in Table 8-5.

TABLE 8-5 Owner’s Actual Payments under Different Conditions (in $1,000)

| Type of Contract | U=0 C=0 |

U=0 C=6%E |

U=4%E C=0 |

U=4%E C=6%E |

U=-4%E C=0 |

U=-4%E C=6%E |

| 1. lump sum 2. unit price 3. cost + fixed % 4. cost + fixed fee 5. cost + Var % 6. target estimate 7. guar. max. cost |

$6,720 6,660 6,600 6,600 6,600 6,600 6,900 |

$7,123 7,060 6,996 6,960 6,996 6,960 6,900 |

$6,720 6,926 6,864 6,840 6,816 6,720 6,900 |

$7,123 7,326 7,260 7,200 7,212 7,080 6,900 |

$6,720 6,394 6,336 6,360 6,384 6,480 6,900 |

$7,123 6,794 6,732 6,720 6,780 6,840 6,900 |

8.6 Principles of Competitive Bidding

Competitive bidding on construction projects involves decision making under uncertainty where one of the greatest sources of the uncertainty for each bidder is due to the unpredictable nature of their competitors. Each bid submitted for a particular job by a contractor will be determined by a large number of factors, including an estimate of the direct job cost, the general overhead, the confidence that the management has in this estimate, project risks identified, and the immediate and long-range objectives of management. So many factors are involved that it is impossible for a particular bidder to attempt to predict exactly what the bids submitted by its competitors will be.

It is useful to think of a bid as being made up of two basic elements: (1) the estimate of direct job cost, which includes direct labor costs, material costs, equipment costs, and direct filed supervision; and (2) the markup or return, which must be sufficient to cover a portion of general overhead costs and allow a fair profit on the investment. A large return can be assured simply by including a sufficiently high markup. However, the higher the markup, the less chance there will be of getting the job. Consequently, a contractor who includes a very large markup on every bid could become bankrupt from lack of business. Conversely, the strategy of bidding with very little markup to obtain high volume is also likely to lead to bankruptcy. Somewhere in between the two extreme approaches to bidding lies an “optimum markup” which considers both the return and the likelihood of being low bidder in such a way that, over the long run, the average return is maximized.

From all indications, most contractors confront uncertain bidding conditions by exercising a high degree of subjective judgment, and each contractor may give different weights to various factors. The decision on the bid price, if a bid is indeed submitted, reflects the contractor’s best judgment on how well the proposed project fits into the overall strategy for the survival and growth of the company, as well as the contractor’s propensity to risk greater profit versus the chance of not getting a contract.

One major concern in bidding competitions is the amount of “money left on the table,” of the difference between the winning and the next best bid. The winning bidder would like the amount of “money left on the table” to be as small as possible. For example, if a contractor wins with a bid of $200,000, and the next lowest bid was $225,000 (representing $25,000 of “money left on the table”), then the winning contractor would have preferred to have bid $220,000 (or perhaps $224,999) to increase potential profits.

Some of the major factors impacting bidding competitions include:

Exogenous Economic Factors

Contractors generally tend to specialize in a submarket of construction and concentrate their work in particular geographic locations. The level of demand in a submarket at a particular time can influence the number of bidders and their bid prices. When work is scarce in the submarket, the average number of bidders for projects will be larger than at times of plenty. The net result of scarcity is likely to be the increase in the number of bidders per project and downward pressure on the bid price for each project in the submarket. At times of severe scarcity, some contractors may cross the line between segments to expand their activities, or move into new geographic locations to get a larger share of the existing submarket. Either action will increase the risks incurred by such contractors as they move into less familiar segments or territories. The trend of market demand in construction and of the economy at large may also influence the bidding decisions of a contractor in other ways. If a contractor perceives drastic increases in labor wages and material prices as a result of recent labor contract settlements, it may take into consideration possible increases in unit prices for determining the direct project cost. Furthermore, the perceptions of increase in inflation rates and interest rates may also cause the contractor to use a higher markup to hedge the uncertainty. Consequently, at times of economic expansion and/or higher inflation rate, contractors are reluctant to commit themselves to long-term fixed price contracts.

Characteristics of Bidding Competition

All other things being equal, the probability of winning a contract diminishes as more bidders participate in the competition. Consequently, a contractor tries to find out as much information as possible about the number and identities of potential bidders on a specific project. Such information is often available in The Dodge Report which provides descriptions of design features and costs of actual projects by building type or similar online publications and services which provide data of potential projects and names of contractors who have taken out plans and specifications. For certain segments, potential competitors may be identified through private contacts, and bidders often confront the same competitors project after project, since they have similar capabilities and interests in undertaking the same type of work, including size, complexity and geographical location of the projects. A general contractor may also obtain information of potential subcontractors from publications such as Business Credit Reports published by Dun and Bradstreet, Inc. However, most contractors form an extensive network with a group of subcontractors with whom they have had previous business transactions. They usually rely on their own experience in soliciting subcontract bids before finalizing a bid price for the project.

Objectives of General Contractors in Bidding

The bidding strategy of some contractors are influenced by a policy of minimum percentage markup for general overhead and profit. However, the percentage markup may also reflect additional factors stipulated by the owner such as high retention and slow payments for completed work, or perceptions of uncontrollable factors in the economy. The intensity of a contractor’s efforts in bidding a specific project is influenced by the contractor’s desire to obtain additional work. The winning of a particular project may be potentially important to the overall mix of work in progress or the cash flow implications for the contractor. The contractor’s decision is also influenced by the availability of key personnel in the contractor organization. The company sometimes wants to reserve its resources for future projects, or it commits itself to the current opportunity for different reasons.

Contractor’s Comparative Advantages

A final important consideration in forming bid prices on the part of contractors are the possible special advantages enjoyed by a particular firm. As a result of lower costs, a particular contractor may be able to impose a higher profit markup yet still have a lower total bid than competitors. These lower costs may result from superior technology, greater experience, better management, better personnel or lower unit costs. A comparative cost advantage is the most desirable of all circumstances in entering a bid competition.

A Bidding Game for Classrooms

Learning the preceding principles and understanding them deeply can take decades of experience. An exercise for early career professionals or for a classroom was developed in 2024 and is described here. It is meant to be played in one to two hours. It can be ended after an arbitrary number of rounds to fit the time available. It is scalable to a room of well over 100 people. An instructor can vary the default parameters described below, after some experience hosting the game. After the game is played, it is worth having a discussion with the participants about what they learned. It has been well received by participants to date.

- Everyone starts with $1,000,000

- Engineers’ estimates are $1,000,000 to $15,000,000 per project

- Actual cost will not include changes:

- P(40%) it is equal to engineer’s estimate

- P(20%) it is 10% above engineer’s estimate

- P(20%) it is 10% below engineer’s estimate

- P(10%) it is 20% above engineer’s estimate

- P(10%) it is 20% below engineer’s estimate

- You pay $100,000 per round to operate

- You pay $25,000 per bid (win or lose)

- You may only carry up to $20,000,000 of project work

- Each project lasts one round, and its actual cost will be released at the beginning of the next round

- Since this is about learning, not winning, participants track their own bids and balance sheets

- To manage volume (make the game scalable between 5-150 participants), each project is awarded to the lowest N bidders, where N = class_size/10

- If your balance goes below zero, you are bankrupt and must wait 4 rounds to rotate back in after re-incorporating under another name

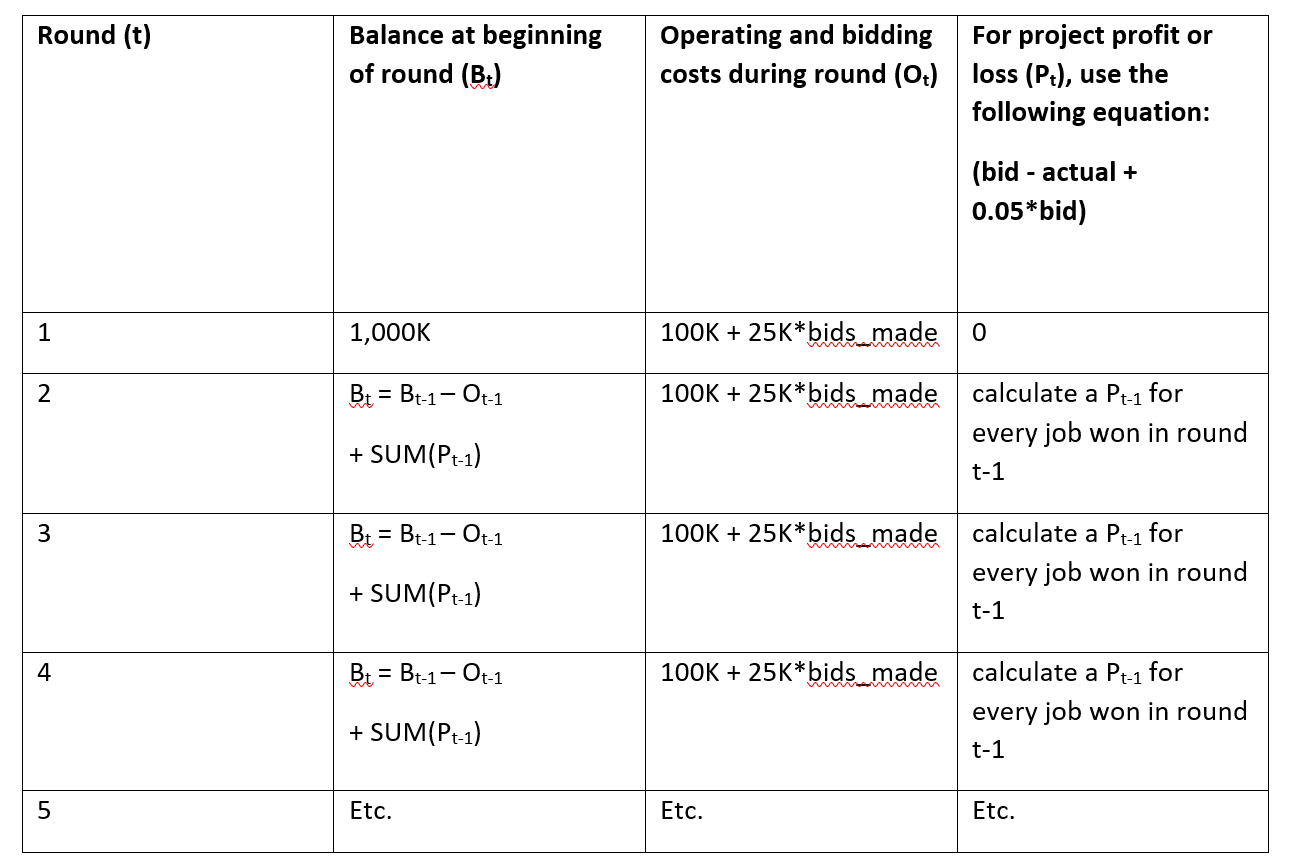

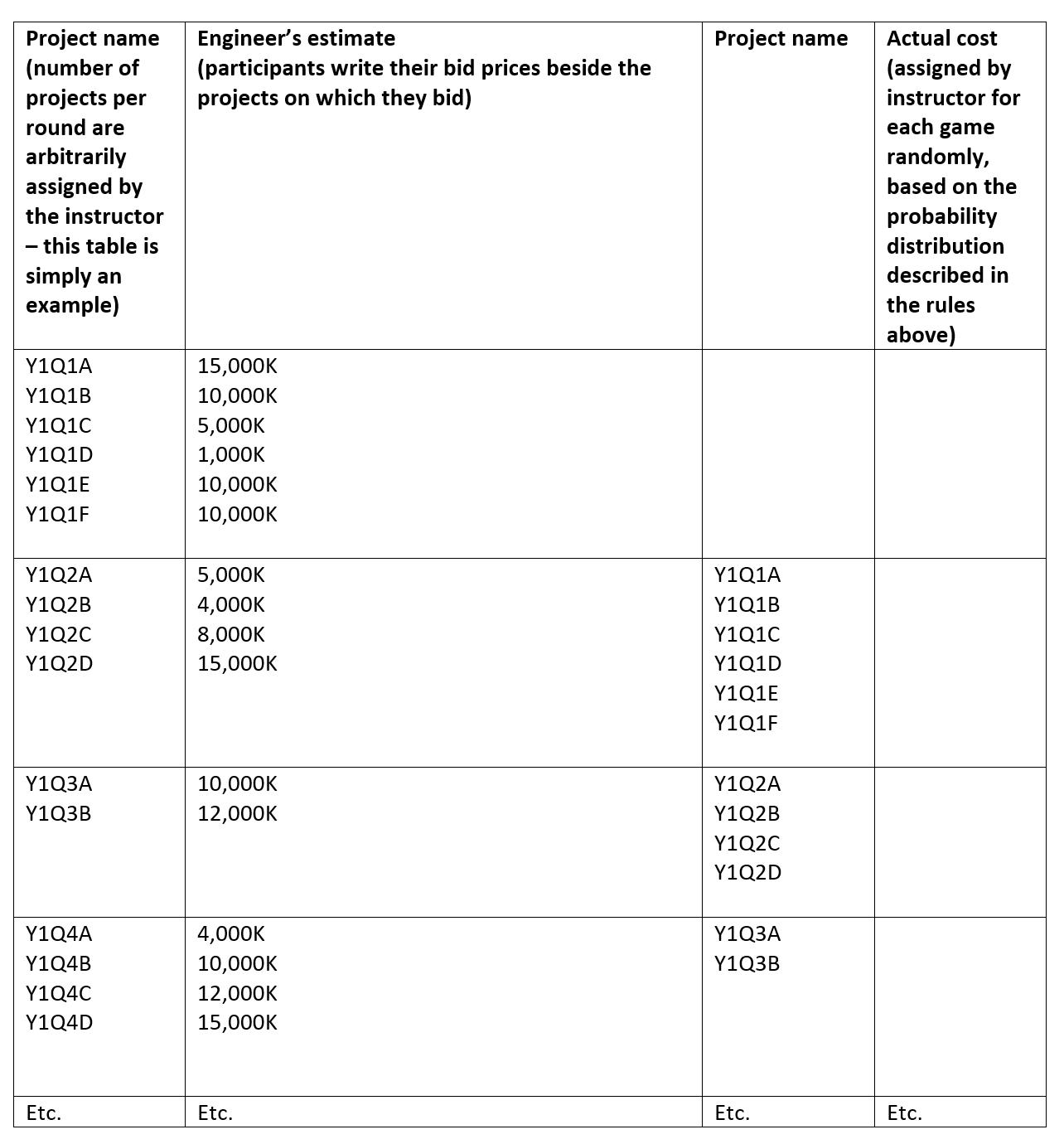

Participants write their bids down before each round and calculate their cash balance using the following table. It may be extended to many rows. About ten rounds per hour can be played, depending on the room and situational dynamics.

Player’s table

Instructor’s project release and performance table (one row per round, and participants see only the current round’s actual costs)

8.7 Principles of Contract Negotiation

Negotiation is another important mechanism for arranging construction contracts. Project managers often find themselves as participants in negotiations, either as principal negotiators or as expert advisors. These negotiations can be complex and often present important opportunities and risks for the various parties involved. For example, negotiation on work contracts can involve issues such as completion date, arbitration procedures, special work item compensation, contingency allowances as well as the overall price. As a general rule, exogenous factors such as the history of a contractor and the general economic climate in the construction industry will determine the results of negotiations. However, the skill of a negotiator can affect the possibility of reaching an agreement, the profitability of the project, the scope of any eventual disputes, and the possibility for additional work among the participants. Thus, negotiations are an important task for many project managers. Even after a contract is awarded on the basis of competitive bidding, there are many occasions in which subsequent negotiations are required as conditions change over time.

In conducting negotiations between two parties, each side will have a series of objectives and constraints. The overall objective of each party is to obtain the most favorable, acceptable agreement. A two party, one issue negotiation illustrates this fundamental point. Suppose that a developer is willing to pay up to $500,000 for a particular plot of land, whereas the owner would be willing to sell the land for $450,000 or more. These maximum and minimum sales prices represent constraints on any eventual agreement. In this example, any purchase price between $450,000 and $500,000 is acceptable to both of the involved parties. This range represents a feasible agreement space. Successful negotiations would conclude in a sales price within this range. Which party receives the $50,000 in the middle range between $450,000 and $500,000 would typically depend upon the negotiating skills and special knowledge of the parties involved. For example, if the developer was a better negotiator, then the sales price would tend to be close to the minimum $450,000 level.

With different constraints, it might be impossible to reach an agreement. For example, if the owner was only willing to sell at a price of $550,000 while the developer remains willing to pay only $500,000, then there would be no possibility for an agreement between the two parties. Of course, the two parties typically do not know at the beginning of negotiations if agreements will be possible. But it is quite important for each party to the negotiation to have a sense of their own reservation price, such as the owner’s minimum selling price or the buyer’s maximum purchase price in the above example. This reservation price is equal to the value of the best alternative to a negotiated agreement.

Poor negotiating strategies adopted by one or the other party may also preclude an agreement even with the existence of a feasible agreement range. For example, one party may be so demanding that the other party simply breaks off negotiations. In effect, negotiations are not a well-behaved solution methodology for the resolution of disputes. Alternative dispute resolution methods such as employment of special arbitrators may be resorted to if negotiation fails. The last resort should be litigation.

The possibility of negotiating failures in the land sale example highlights the importance of negotiating style and strategy with respect to revealing information. Style includes the extent to which negotiators are willing to seem reasonable, the type of arguments chosen, the forcefulness of language used, etc. Clearly, different negotiating styles can be more or less effective. Cultural factors are also extremely important. American and Japanese negotiating styles differ considerably, for example. Revealing information is also a negotiating decision. In the land sale case, some negotiators would readily reveal their reserve or constraint prices, whereas others would conceal as much information as possible (i.e. “play their cards close to the vest”) or provide misleading information.

In light of these tactical problems, it is often beneficial to all parties to adopt objective standards in determining appropriate contract provisions. These standards would prescribe a particular agreement or a method to arrive at appropriate values in a negotiation. Objective standards can be derived from numerous sources, including market values, precedent, professional standards, what a court would decide, etc. By using objective criteria of this sort, personalities and disruptive negotiating tactics do not become impediments to reaching mutually beneficial agreements.

With additional issues, negotiations become more complex both in procedure and in result. With respect to procedure, the sequence in which issues are defined or considered can be very important. For example, negotiations may proceed on an issue-by-issue basis, and the outcome may depend upon the exact sequence of issues considered. Alternatively, the parties may proceed by proposing complete agreement packages and then proceed to compare packages. With respect to outcomes, the possibility of the parties having different valuations or weights on particular issues arises. In this circumstance, it is possible to trade-off the outcomes on different issues to the benefit of both parties. By yielding on an issue of low value to oneself but high value to the other party, concessions on other issues may be obtained.

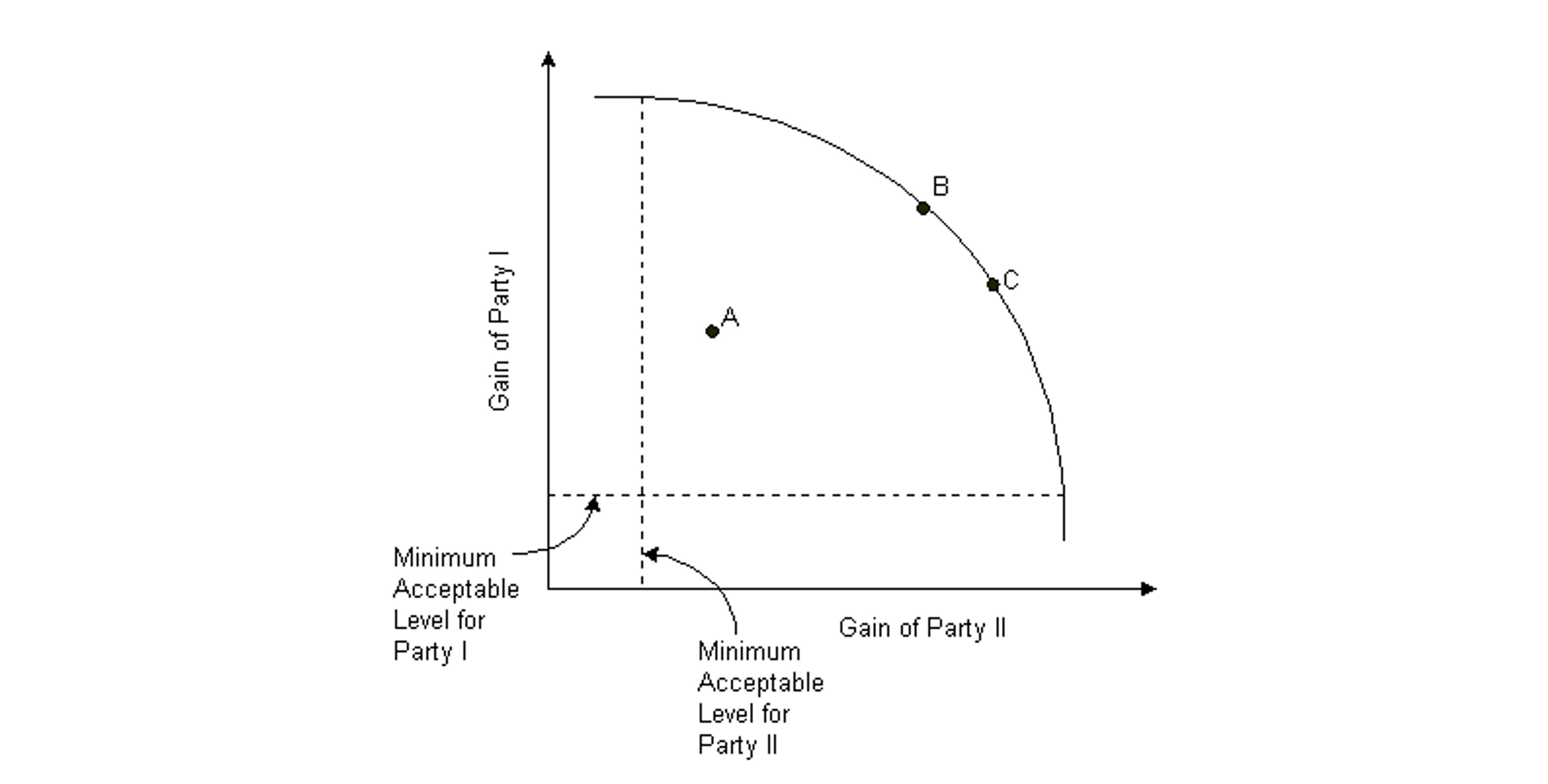

The notion of Pareto optimal agreements can be introduced to identify negotiated agreements in which no change in the agreement can simultaneously make both parties better off. Figure 8-1 illustrates Pareto optimal agreements which can be helpful in assessing the result of multiple issue negotiations. In this figure, the axes represent the satisfaction or desirability of agreements to the parties, denoted I and II. This representation assumes that one can place a dollar or utility value on various agreements reached in a multiple-issue negotiation between two parties. Points in the graph represent particular agreements on the different issues under consideration. A particular point may be obtained by more than one contract agreement. The curved line encloses the set of all feasible agreements; any point in this area is an acceptable agreement. Each party has a minimum acceptable satisfaction level in this graph. Points on the interior of this feasible area represent inferior agreements since some other agreement is possible that benefits both parties. For example, point B represents a more desirable agreement than point A. In the previous example, point B might represent a purchase price of $490,000 and an immediate purchase, whereas point A might represent a $475,000 sale price and a six-month delay. The feasible points that are not inferior constitute the set of Pareto optimal or efficient agreements; these points lie on the north-east quadrant of the feasible region as marked on the figure.

Figure 8-1 Illustration of a Pareto Optimal Agreement Set

The definition of Pareto optimal agreements allows one to assess at least one aspect of negotiated outcomes. If two parties arrive at an inferior agreement (such as point A in Figure 8-1), then the agreement could be improved to the benefit of both parties. In contrast, different Pareto optimal agreements (such as points B and C in Figure 8-1) can represent widely different results to the individual parties but do not have the possibility for joint improvement.

Of course, knowledge of the concept of Pareto optimal agreements does not automatically give any guidance on what might constitute the best agreements. Much of the skill in contract negotiation comes from the ability to invent new options that represent mutual gains. For example, devising contract incentives for speedier completion of projects may result in benefits to both contractors and the owner.

Example 8-7: Effects of different value perceptions.

Suppose that the closing date for sale of the land in the previous case must also be decided in negotiation. The current owner would like to delay the sale for six months, which would represent rental savings of $10,000. However, the developer estimates that the cost of a six-month delay would be $20,000. After negotiation, suppose that a purchase price of $475,000 and a six-month purchase delay are agreed upon. This agreement is acceptable but not optimal for both parties. In particular, both sides would be better off if the purchase price was increased by $15,000 and immediate closing instituted. The current owner would receive an additional payment of $15,000, incur a cost of $10,000, and have a net gain of $5,000. Similarly, the developer would pay $15,000 more for the land but save $20,000 in delay costs. While this superior result may seem obvious and easily achievable, recognizing such opportunities during a negotiation becomes increasingly difficult as the number and complexity of issues increases.

8.8 Negotiation Simulation: An Example

This construction negotiation game simulates a contract negotiation between a utility, “CMG Gas” and a design/construct firm, “Pipeline Constructors, Inc.” [4] The negotiation involves only two parties but multiple issues. Participants in the game are assigned to represent one party or the other and to negotiate with a designated partner. In a class setting, numerous negotiating partners are created. The following overview from the CMG Gas participants’ instructions describes the setting for the game:

CMG Gas has the opportunity to provide natural gas to an automobile factory under construction. Service will require a new sixteen-mile pipeline through farms and light forest. The terrain is hilly with moderate slopes, and equipment access is relatively good. The pipeline is to be buried three feet deep. Construction of the pipeline itself will be contracted to a qualified design/construction firm, while required compression stations and ancillary work will be done by CMG Gas. As project manager for CMG Gas, you are about to enter negotiations with a local contractor, “Pipeline Constructors, Inc.” This firm is the only local contractor qualified to handle such a large project. If a suitable contract agreement cannot be reached, then you will have to break off negotiations soon and turn to another company.

The Pipeline Constructors, Inc. instructions offers a similar overview.

To focus the negotiations, the issues to be decided in the contract are already defined:

- Duration

The final contract must specify a required completion date. - Penalty for Late Completion

The final contract may include a daily penalty for late project completion on the part of the contractor. - Bonus for Early Completion

The final contract may include a daily bonus for early project completion. - Report Format

Contractor progress reports will either conform to the traditional CMG Gas format or to a new format proposed by the state. - Frequency of Progress Reports

Progress reports can be required daily, weekly, bi-weekly or monthly. - Conform to Pending Legislation Regarding Pipeline Marking

State legislation is pending to require special markings and drawings for pipelines. The parties have to decide whether to conform to this pending legislation. - Contract Type

The construction contract may be a flat fee, a cost plus a percentage profit, or a guaranteed maximum with cost plus a percentage profit below the maximum. - Amount of Flat Fee

If the contract is a flat fee, the dollar amount must be specified. - Percentage of Profit

If the contract involves a percentage profit, then the percentage must be agreed upon. - CMG Gas Clerk on Site

The contract may specify that a CMG Gas Clerk may be on site and have access to all accounts or that only progress reports are made by Pipeline Constructors, Inc. - Penalty for Late Starting Date

CMG Gas is responsible for obtaining right-of-way agreements for the new pipeline. The parties may agree to a daily penalty if CMG Gas cannot obtain these agreements.

A final contract requires an agreement on each of these issues, represented on a form signed by both negotiators.

As a further aid, each participant is provided with additional information and a scoring system to indicate the relative desirability of different contract agreements. Additional information includes items such as estimated construction cost and expected duration as well as company policies such as desired reporting formats or work arrangements. This information may be revealed or withheld from the other party depending upon an individual’s negotiating strategy. The numerical scoring system includes point totals for different agreements on specific issues, including interactions among the various issues. For example, the amount of points received by Pipeline Constructors, Inc. for a bonus for early completion increases as the completion date become later. An earlier completion becomes more likely with a later completion date, and hence the probability of receiving a bonus increases, so the resulting point total likewise increases.

The two firms have differing perceptions of the desirability of different agreements. In some cases, their views will be directly conflicting. For example, increases in a flat fee imply greater profits for Pipeline Constructors, Inc. and greater costs for CMG Gas. In some cases, one party may feel strongly about a particular issue, whereas the other is not particularly concerned. For example, CMG Gas may want a clerk on site, while Pipeline Constructors, Inc. may not care. As described in the previous section, these differences in the evaluation of an issue provide opportunities for negotiators. By conceding an unimportant issue to the other party, a negotiator may trade for progress on an issue that is more important to his or her firm. Examples of instructions to the negotiators appear below.

Instructions to the Pipelines Constructors, Inc. Representative

After examining the project site, your company’s estimators are convinced that the project can be completed in thirty-six weeks. In bargaining for the duration, keep two things in mind; the longer past thirty-six weeks the contract duration is, the more money that can be made off the “bonuses for being early” and the chances of being late are reduced. That reduces the risk of paying a “penalty for lateness”.

Throughout the project the gas company will want progress reports. These reports take time to compile and therefore the fewer you need to submit, the better. In addition, State law dictates that the Required Standard Report be used unless the contractor and the owner agree otherwise. These standard reports are even more time consuming to produce than more traditional reports.

The State Legislature is considering a law that requires accurate drawings and markers of all pipelines by all utilities. You would prefer not to conform to this uncertain set of requirements, but this is negotiable.

What type of contract and the amount your company will be paid are two of the most important issues in negotiations. In the Flat Fee contract, your company will receive an agreed amount from CMG Gas. Therefore, when there are any delay or cost overruns, it will be the full responsibility of your company. with this type of contract, your company assumes all the risk and will in turn want a higher price. Your estimators believe a cost and contingency amount of 4,500,000 dollars in this case. You would like a higher fee, of course.

With the Cost-Plus Contract, the risk is shared by the gas company and your company. With this type of contract, your company will bill CMG Gas for all of its costs, plus a specified percentage of those costs. In this case, cost overruns will be paid by the gas company. Not only does the percentage above cost have to be decided upon but also whether or not your company will allow a Field Clerk from the gas company to be at the job site to monitor reported costs. Whether or not they are around is of no concern to your company since its policy is not to inflate costs. This point can be used as a bargaining weapon.

Finally, your company is worried whether the gas company will obtain the land rights to lay the pipe. Therefore, you should demand a penalty for the potential delay of the project starting date.

Instructions to the CMG Gas Company Representative

In order to satisfy the auto manufacturer, the pipeline must be completed in forty weeks. An earlier completion date will not result in receiving revenue any earlier. Thus, the only reason to bargain for shorter duration is to feel safer about having the project done on time. If the project does exceed the forty week maximum, a penalty will have to be paid to the auto manufacturer. Consequently, if the project exceeds the agreed upon duration, the contractor should pay you a penalty. The penalty for late completion might be related to the project duration. For example, if the duration is agreed to be thirty-six weeks, then the penalty for being late need not be so severe. Also, it is normal that the contractor gets a bonus for early completion. Of course, completion before forty weeks doesn’t yield any benefit other than your own peace of mind. Try to keep the early bonus as low as possible.

Throughout the project you will want progress reports. The more often these reports are received, the better to monitor the progress and proactively address developing problems. State law dictates that the Required Standard Report be used unless the contractor and the owner agree otherwise. These reports are very detailed and time consuming to review. You would prefer to use the traditional CMG Gas reports.

The state legislature is considering a law that requires accurate drawings and markers of all pipelines by all utilities. For this project it will cost an additional $250,000 to do this now, or $750,000 to do this when the law is passed.

One of the most important issues is the type of contract, and the amount of be paid. The Flat Fee contract means that CMG Gas will pay the contractor a set amount. Therefore, when there are delays and cost overruns, the contractor assumes full responsibility for the individual costs. However, this evasion of risk must be paid for and results in a higher price. If Flat Fee is chosen, only the contract price is to be determined. Your company’s estimators have determined that the project should cost about $5,000,000.

The Cost-Plus Percent contract may be cheaper, but the risk is shared. With this type of contract, the contractor will bill the gas company for all costs, plus a specified percentage of those costs. In this case, cost overruns will be paid by the gas company. If this type of contract is chosen, not only must the profit percentage be chosen, but also whether or not a gas company representative will be allowed on site all of the time acting as a Field Clerk, to ensure that a proper amount of material and labor is billed. The usual percentage agreed upon is about ten percent.

Contractors also have a concern whether or not they will receive a penalty if the gas right-of-way is not obtained in time to start the project. In this case, CMG Gas has already secured the right-of-ways. But, if the penalty is too high, this is a dangerous precedent for future negotiations. However, you might try to use this as a bargaining tool.

Example 8-8: An example of a negotiated contract

A typical contract resulting from a simulation of the negotiation between CMG Gas and Pipeline Constructors, Inc. appears in Table 8-6. An agreement with respect to each pre-defined issue is included, and the resulting contract signed by both negotiators.

TABLE 8-6 Example of a Negotiated Contract between CMG Gas and Pipeline Constructors, Inc

| Duration | 38 weeks |

| Penalty for Late Completion | $6,800 per day |

| Bonus for Early Completion | $0 per day |

| Report Format | traditional CMG form |

| Frequency of Progress Reports | weekly |

| Conform to Pending Pipeline Marking Legislation | yes |

| Contract Type | flat fee |

| Amount of Flat Fee | $5,050,000 |

| Percentage of Profit | Not applicable |

| CMG Gas Clerk on Site | yes |

| Penalty for Late Starting Date | $3,000 per day |

| Signed:

CMG Gas Representative Pipeline Constructors, Inc. |

Example 8-9: Scoring systems for the negotiated contract games

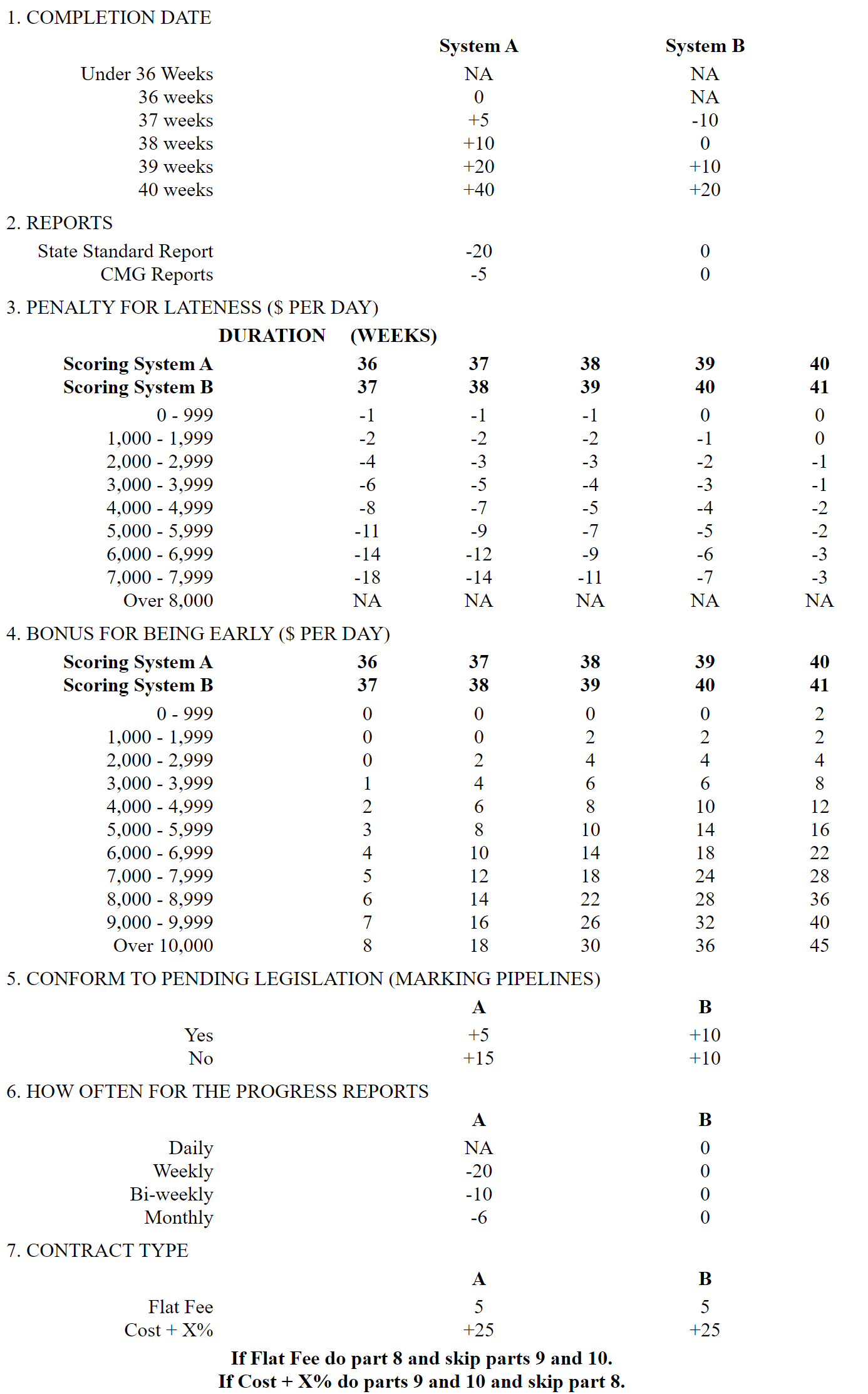

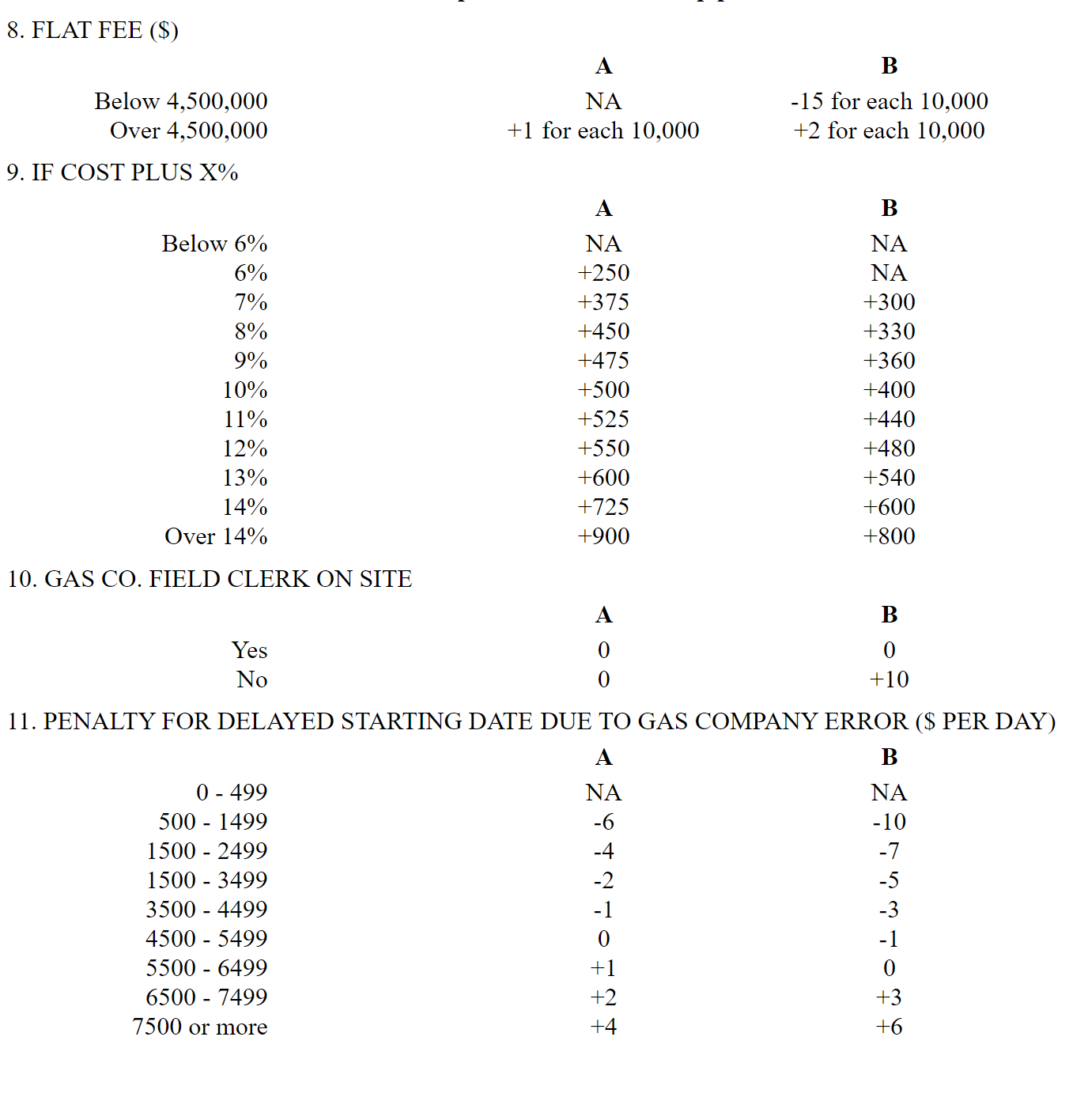

To measure the performance of the negotiators in the previous example, a scoring system is needed for the representative of Pipeline Constructors, Inc. and another scoring system for the representative of CMG Gas. These scoring systems for the companies associated with the issues described in Example 8-7 are designated as system A.

In order to make the negotiating game viable for classroom use, another set of instructions for each company is described in this example, and the associated scoring systems for the two companies are designated as System B. In each game play, the instructor may choose a different combination of instructions and negotiating teams, leading to four possible combinations of scoring systems for Pipeline Constructors, Inc. and CMG Gas. [5]

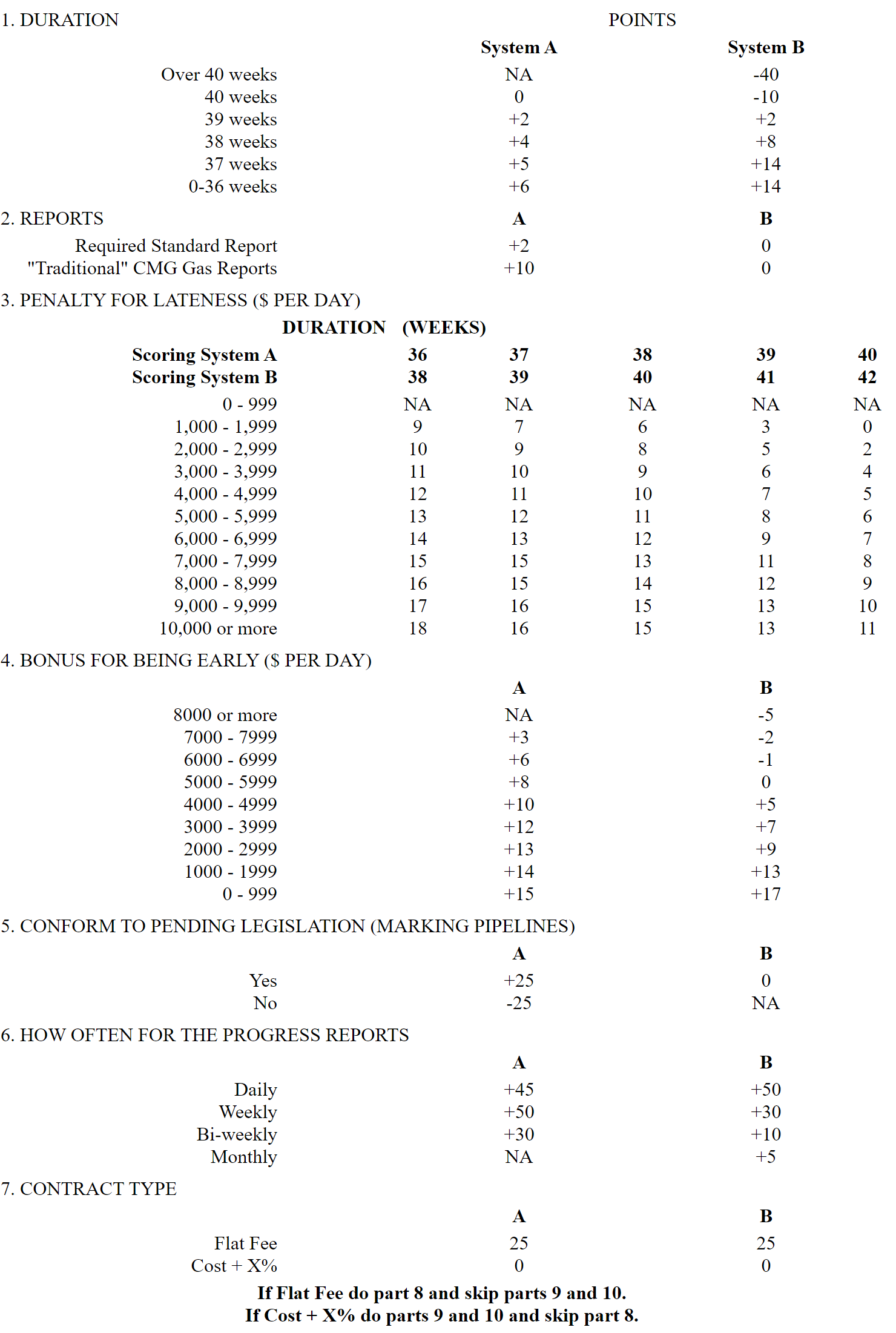

Instruction To The Pipeline Constructors, Inc. Representative

In order to help you, your boss has left you with a scoring table for all the issues and alternatives. Two different scoring systems are listed here; you will be assigned to use one or the other. Instructions for scoring system A are included in Section 8.9. The instructions for scoring system B are as follows:

After examining the site, your estimator believes that the project will require 38 weeks. You are happy to conform with any reporting or pipeline marking system, since your computer-based project control and design systems can easily produce these submissions. You would prefer to delay the start of the contract as long as possible, since your forces are busy on another job; hence, you do not want to impose a penalty for late start. Try to maximize the amount of points, as they reflect profit brought into your company, or a cost savings. In Parts 3 and 4, be sure to use the project duration agreed upon to calculate your score. Finally, do not discuss your scoring system with the CMG Gas representative; this is proprietary information!

SCORING FOR PIPELINE CONSTRUCTORS, INC.

NOTE: NA means not acceptable and the deal will not be approved by your boss with any of these provisions. also, the alternatives listed are the only ones in the context of this problem; no other alternatives are acceptable.

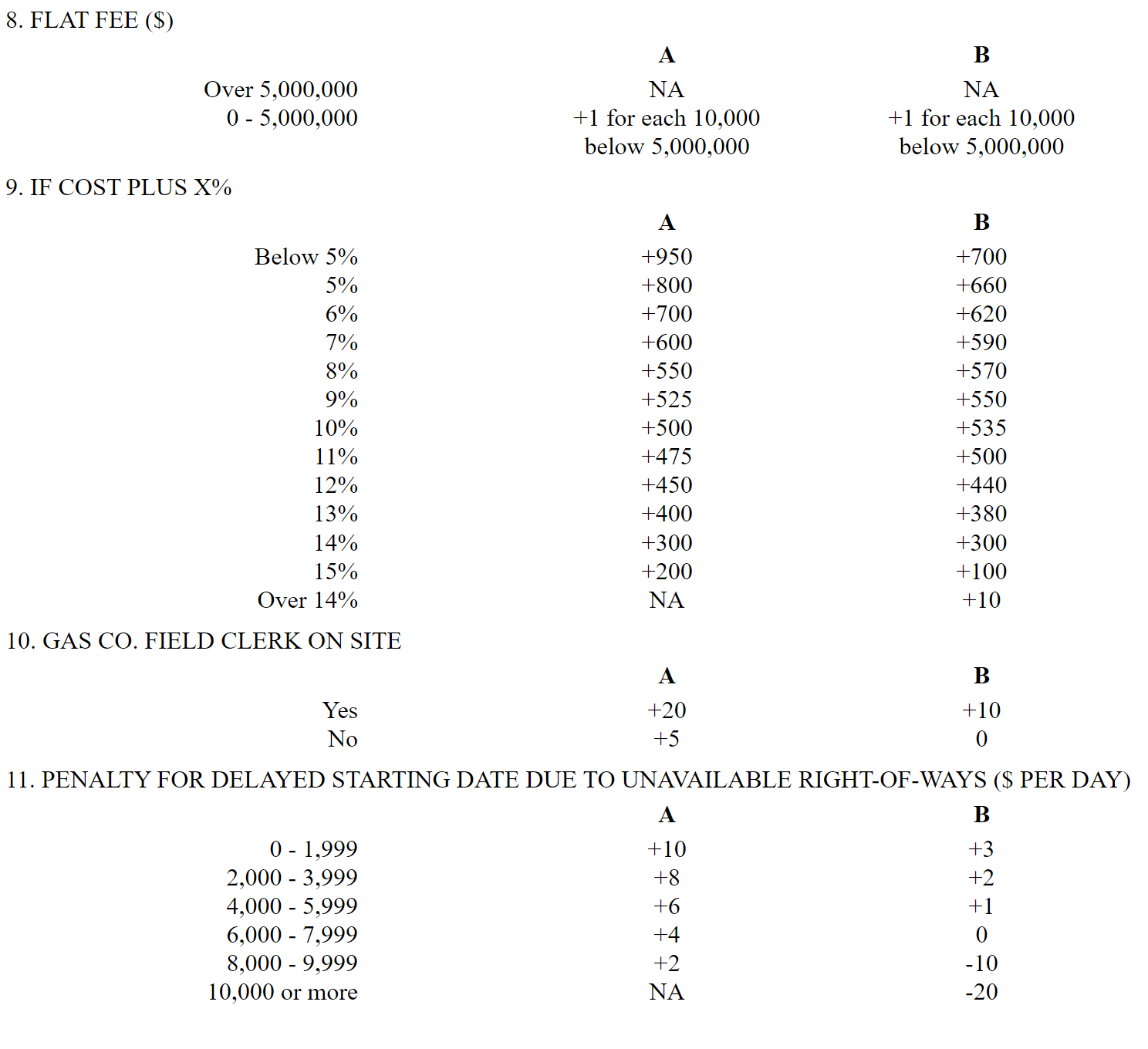

Instructions to the CMG Gas Company Representative

In order to help you, your boss has left you with a scoring table for all the issues and alternatives. Two different scoring systems are listed here; you will be assigned to use one or the other. Instructions for scoring system A are included in Section 8.9. The instructions for scoring system B are described as follows:

Your contract with the automobile company provides an incentive for completion of the pipeline earlier than 38 weeks and a penalty for completion after 38 weeks. To insure timely completion of the project, you would like to receive detailed project reports as often as possible.

Try to maximize the number of points from the final contract provisions; this corresponds to minimizing costs. Do not discuss your scoring systems with Pipeline Constructors, Inc.

SCORING SYSTEM FOR CMG GAS

NOTE: NA means not acceptable and the deal will not be approved by your boss with any of these provisions. If you can’t negotiate a contract, your score will be +450. Also, the alternatives listed are the only ones in the context of this problem no other alternatives are acceptable.

8.9 Resolution of Contract Disputes

Once a contract is reached, a variety of problems may emerge during the course of work. Disputes may arise over quality of work, over responsibility for delays, over appropriate payments due to changed conditions, or a multitude of other considerations. Resolution of contract disputes is an important task for project managers. The mechanism for contract dispute resolution can be specified in the original contract or, less desirably, decided when a dispute arises.

The most prominent mechanism for dispute resolution is adjudication in a court of law. This process tends to be expensive and time consuming since it involves legal representation and waiting in queues of cases for available court times. Any party to a contract can bring a suit. In adjudication, the dispute is decided by a neutral, third party with no necessary specialized expertise in the disputed subject. After all, it is not a prerequisite for judges to be familiar with construction procedures! Legal procedures are highly structured with rigid, formal rules for presentations and fact finding. On the positive side, legal adjudication strives for consistency and predictability of results. The results of previous cases are published and can be used as precedents for resolution of new disputes.

Negotiation among the contract parties is a second important dispute resolution mechanism. These negotiations can involve the same sorts of concerns and issues as with the original contracts. Negotiation typically does not involve third parties such as judges. The negotiation process is usually informal, unstructured and relatively inexpensive. If an agreement is not reached between the parties, then adjudication is a possible remedy.

A third dispute resolution mechanism is the resort to arbitration or mediation and conciliation. In these procedures, a third party serves a central role in the resolution. These outside parties are usually chosen by mutually agreement of the parties involved and will have specialized knowledge of the dispute subject. In arbitration, the third party may make a decision which is binding on the participants. In mediation and conciliation, the third party serves only as a facilitator to help the participants reach a mutually acceptable resolution. Like negotiation, these procedures can be informal and unstructured.

Finally, the high cost of adjudication has inspired a series of non-traditional dispute resolution mechanisms that have some of the characteristics of judicial proceedings. These mechanisms include:

- Private judging in which the participants hire a third-party judge to make a decision,

- Neutral expert fact-finding in which a third party with specialized knowledge makes a recommendation, and

- Mini-trial in which legal summaries of the participants’ positions are presented to a jury comprised of principals of the affected parties.

Some of these procedures may be court sponsored or required for particular types of disputes.

While these various disputes resolution mechanisms involve varying costs, it is important to note that the most important mechanism for reducing costs and problems in dispute resolution is the reasonableness of the initial contract among the parties as well as the competence of the project manager.

8.10 References

- Au, T., R.L. Bostleman and E.W. Parti, “Construction Management Game-Deterministic Model,” Asce Journal of the Construction Division, Vol. 95, 1969, pp. 25-38.

- Building Research Advisory Board, Exploratory Study on Responsibility, Liability and Accountability for Risks in Construction, National Academy of Sciences, Washington, D.C., 1978.

- Construction Industry Cost Effectiveness Project, “Contractual Arrangements,” Report A-7, The Business Roundtable, New York, October 1982.

- Dudziak, W. and C. Hendrickson, “A Negotiating Simulation Game,” ASCE Journal of Management in Engineering, Vol. 4, No. 2, 1988.

- Graham, P.H., “Owner Management of Risk in Construction Contracts,” Current Practice in Cost Estimating and Cost Control, Proceedings of an ASCE Conference, Austin, Texas, April 1983, pp. 207-215.

- Green, E.D., “Getting Out of Court — Private Resolution of Civil Disputes,” Boston Bar Journal, May-June 1986, pp. 11-20.

- Park, William R., The Strategy of Contracting for Profit, 2nd Edition, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1986.

- Raiffa, Howard, The Art and Science of Negotiation, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1982.

- Walker, N., E.N. Walker and T.K. Rohdenburg, Legal Pitfalls in Architecture, Engineering and Building Construction, 2nd Edition, McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, 1979.

8.11 Problems

(1) Suppose that in Example 8-5, the terms for the guaranteed maximum cost contract are such that change orders will not be compensated if their total cost is within 3% of the original estimate, but they will be compensated in full for the amount beyond 3% of the original estimate. If all other conditions remain unchanged, determine the contractor’s profit and the owner’s actual payment under this contract for the following conditions of U and C:

(2) Suppose that in Example 8-5, the terms of the target estimate contract call for N = 0.3 instead of N = 0.5, meaning that the contractor will receive 30% of the savings. If all other conditions remain unchanged, determine the contractor’s profit and the owner’s actual payment under this contract for the given conditions of U and C.

(3) Suppose that in Example 8-5, the terms of the cost-plus variable percentage contract allow an incentive bonus for early completion and a penalty for late completion of the project. Let D be the number of days early, with negative value denoting D days late. The bonus per days early or the penalty per day late with be T dollars. The agreed formula for owner’s payment is:

P = R(2E – A + C) + A + C + DT(1 + 0.4C/E)

The value of T is set at $5,000 per day, and the project is completed 30 days behind schedule. If all other conditions remain unchanged, find the contractor’s profit and the owner’s actual payment under this contract for the given conditions of U and C.

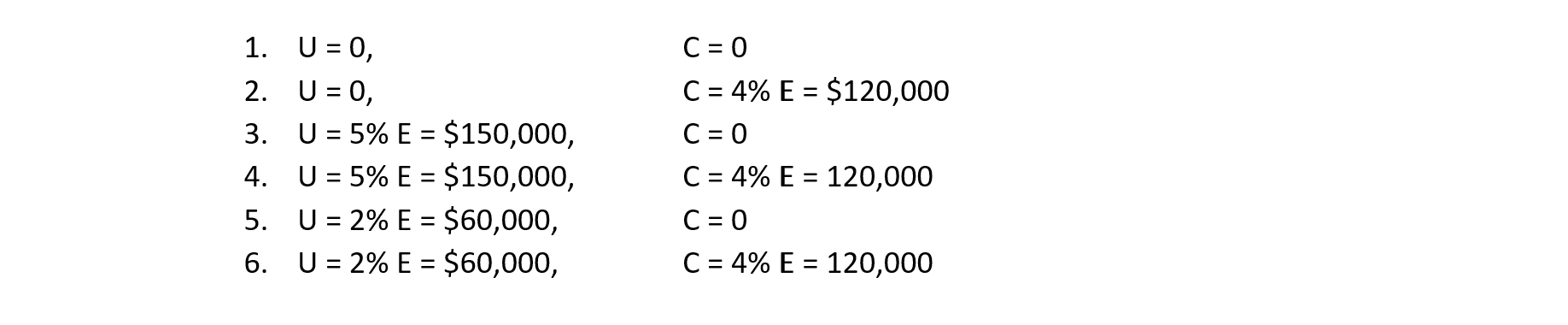

(4) Consider a construction project for which the contractor’s estimate is $3,000,000. For various types of contracts, R = 10%, R1 = 3%, R2 = 1.5%, R3 = 6% and N = 0.6. The contractor is not compensated for change orders under the guaranteed maximum cost contract if the total cost for the change order is within 5% ($150,000) of the original estimate. Determine the contractor’s gross profit for each of the seven types of construction contracts for each of the following conditions of U and C:

(5) Using the data in Problem 4, determine the owner’s actual payment for each of the seven types of construction contracts for the same conditions of U and C.

(6) Suppose that in Problem 4, the terms of the guaranteed maximum cost contract are such that change orders will not be compensated if their total cost is within 3% of the original estimate, but they will be compensated in full for the amount beyond 3% of the original estimate. If all conditions remained unchanged, determine the contractor’s profit and the owner’s actual payment under this contract for the following conditions of U and C:

(7) Suppose that in Problem 4, the terms of the target estimate contract call for N = 0.7 instead of N = 0.3, meaning that the contractor will receive 70% of the savings. If all other conditions remain unchanged, determine the contractor’s profit and the owner’s actual payment under this contract for the given conditions of U and C.

(8) Suppose that in Problem 4, the terms of the cost-plus variable percentage contract allow an incentive bonus for early completion and a penalty for late completion of the project. Let D be the number of days early, with negative value denoting D days late. The bonus per days early or the penalty per day late will be T dollars. The agreed formula for owner’s payment is:

P = R(2E – A + C) + A + C + DT(1 + 0.2C/E)

The value of T is set at $ 10,000 per day, and the project is completed 20 days ahead schedule. If all other conditions remain unchanged, find the contractor’s profit and the owner’s actual payment under this contract for the given conditions of U and C.

(9) In playing the construction negotiating game described in Section 8.8, your instructor may choose one of the following combinations of companies and issues leading to different combinations of the scoring systems:

| Pipeline Constructors Inc. | CMG Gas | |

| a. b. c. d. |

System A System A System B System B |

System A System B System A System B |

Since the scoring systems are confidential information, your instructor will not disclose the combination used for the assignment. Your instructor may divide the class into groups of two students, each group acting as negotiators representing the two companies in the game. To keep the game interesting and fair, do not try to find out the scoring system of your negotiating counterpart. To seek insider information is unethical and illegal!

8.12 Footnotes

- These examples are taken directly from A Construction Industry Cost Effectiveness Project Report, “Contractual Arrangements,” The Business Roundtable, New York, Appendix D, 1982. Permission to quote this material from the Business Roundtable is gratefully acknowledged. Back

- See C.D. Sutliff and J.G. Zack, Jr. “Contract Provisions that Ensure Complete Cost Disclosures”, Cost Engineering, Vol. 29, No. 10, October 1987, pp. 10-14. Back

- Arkansas Rice Growers v. Alchemy Industries, Inc., United States Court of Appeals, Eighth Circuit, 1986. The court decision appears in 797 Federal Reporter, 2d Series, pp. 565-574. Back

- This game is further described in W. Dudziak and C. Hendrickson, “A Negotiation Simulation Game,” ASCE Journal of Management in Engineering, Vol. 4, No. 2, 1988. Back