Vol. 1, No. 2 (December 2023)

LifeLabs: The Ethics of Responding to a Ransomware Cyber Attack

Ron Babin

All figures in Canadian dollars unless otherwise noted.

According to the Privacy Commissioner of Ontario, in late 2019, the LifeLabs information systems were hacked by cyber criminals who gained access to records and data of approximately 15 million LifeLabs customers.[1] The data accessed included name, address, email, customer logins and passwords, health card numbers, credit card numbers and lab test results. The cyber criminals penetrated the company’s information systems, extracted data, and demanded a ransom.

On December 17, 2019, LifeLabs’ CEO Charles Brown sent a public notice to customers describing the cyber attack.[2] After apologizing for the cyber attack, he outlined the steps taken to protect customer information, including hiring cybersecurity experts, paying the ransom after consultation with experts to retrieve the data, and engaging law enforcement.

The Privacy Commissioners in Ontario[3] and British Columbia began investigating the attack shortly after they were notified, as required by law.

The LifeLabs Ransomware Attack

LifeLabs was a Canadian company that provided health diagnostics to patients and doctors. It operated primarily in British Columbia (BC) and in Ontario, with a few labs in other provinces. LifeLabs offered a range of medical tests, from standard lab testing to genetic and naturopathic testing. LifeLabs was one of the largest medical testing companies in the world and performed over 112 million laboratory tests for Canadians each year. The Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS) owned LifeLabs at the time of the cyber attack.

Senior executives at LifeLabs who were responsible for ransom decisions were President and CEO Charles Brown and Chair of the Board of Directors Jon Hantho. Charles Brown joined LifeLabs in 2018. Jon Hantho became chair of the board in April 2019.

Ransomware

According to Gartner, ransomware was a form of cyber extortion where an external hacker “threatens to seize, damage or release electronic data owned by the victim” using “malicious software that infiltrates computer systems or networks and encrypts data, holding it hostage until the victim pays a ransom.”[4] The hacker would then copy or exfiltrate data, and threaten to publish the data to embarrass the victim. As well, exfiltrated data could be used in other criminal ways, such as identity theft using credit card and personal information.

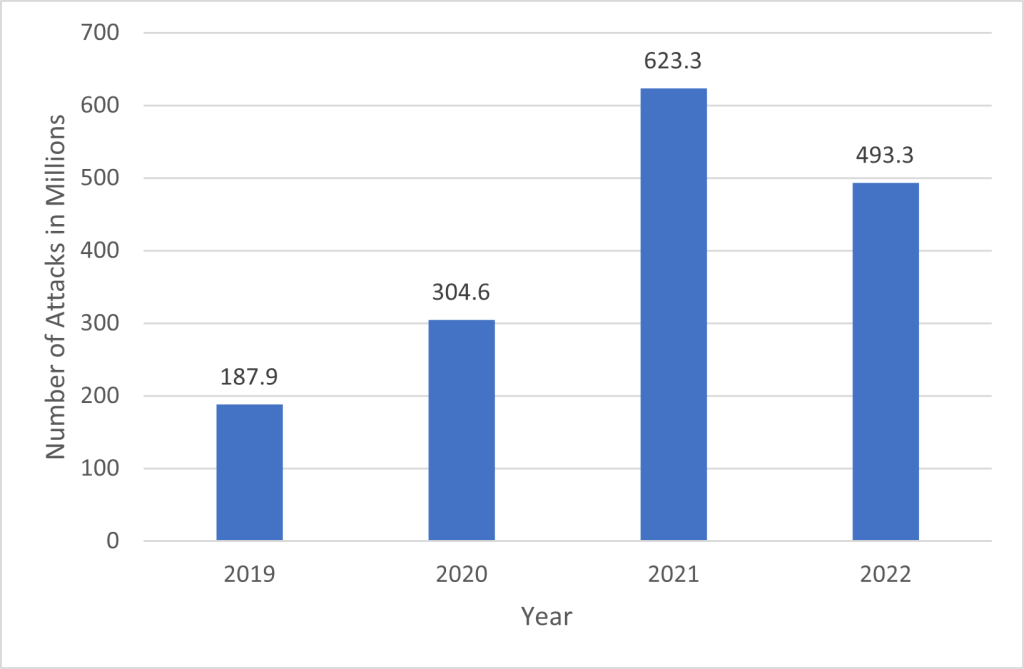

Ransomware had been a growing global concern for all organizations.[5] The number of reported ransomware attacks worldwide more than tripled from 2019 to 2021. The volume of attacks declined slightly in 2022, with just under 500 million ransomware attacks reported. depicts the recent growth in worldwide ransomware attacks reported Figure 1 – Annual Number of Ransomware Attacks Worldwide depicts the recent growth in worldwide ransomware attacks. .

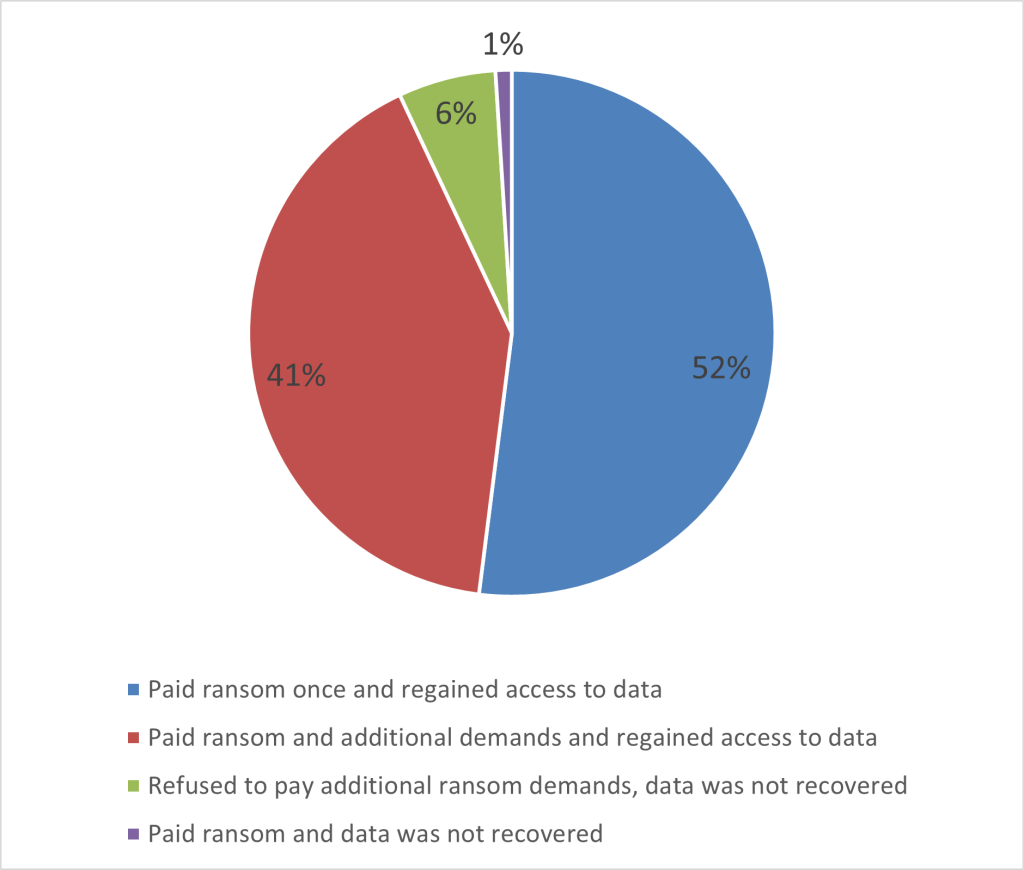

The prospects of regaining access to the stolen data were reasonably good once the ransom has been paid, and most organizations responded with some form of ransom payment. According to Statista, over 90% of organizations that paid ransom did regain access to their data.[6]However, for 41% of those who made the initial payment, the attackers demanded additional payments before access to the data was restored. A small percentage (6%) refused to pay additional ransom demands and their data was not recovered. Only 1% of victims who paid the ransom did not regain access to their data. Figure 2 – What Happened When Ransom Was Paid? shows what happened when ransom was paid.

Paying ransom was not illegal unless the attack organization has been sanctioned by government — for example, if it was listed as a terrorist organization. Many law enforcement agencies, such as the F.B.I., did not support paying the ransom and encouraged executives to consider all options to protect their stakeholders before paying any ransom. As Gartner noted, “approximately 80% of organizations that pay ransom demands end up being exposed to another attack. Moreover, investing in ransomware protection measures generally cost less than paying the ransom.”[7]

Along with the dramatic growth in attacks, the ransomware insurance industry had grown, with over 100 companies providing some form of cybersecurity insurance. However, the rising frequency and demands of ransomware attacks had caused a significant increase in cyber insurance premiums. According to Roger Grimes, “Today, most organizations seeking cybersecurity insurance coverage face far fewer choices and will have to prove they have fairly strong cyber defences to get any policy. … Insurance firms are looking for clients who take cybersecurity defence seriously. … Companies covered by cybersecurity insurance are more likely to pay the ransom because all the money isn’t coming out of their pocket”; hackers understood this and specifically targeted organizations that were known to be insured.[8]

LifeLabs Responded to the Attack

In reaction to the cyber attack, LifeLabs offered customers cybersecurity protection.[9] The protection included credit monitoring and fraud insurance for one year. As well, LifeLabs committed to monitoring the dark web to identify potentially exposed personal information. Lastly, LifeLabs provided identity theft insurance to protect against potential damages related to identity theft and fraud. LifeLabs’ CEO Charles Brown confirmed to customers that: “Our cybersecurity firms have advised that the risk to our customers in connection with this cyber attack is low and that they have not found any public disclosure of customer data as part of their investigations.”[10]

Six months after the attack, LifeLabs CEO Charles Brown further acknowledged the breach in a statement to customers: “I cannot change what happened, but I assure you that I have made every effort toward making change to provide services you can trust.” He then identified several changes, such as appointing a chief information security officer (CISO) and investing $50 million to achieve ISO 27001 certification through an accelerated information security management program. He confirmed that cybersecurity firms continued to monitor the dark web and no public disclosure of customer data had been identified from the attack.[11]

Governments Investigated; Customers Sued

In early 2020, Privacy Commissioners in Ontario, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia conducted their investigations of the reported data breach. The Saskatchewan privacy commissioner published their investigation findings on June 9, 2020.[12] The commissioner found that “because a fulsome, detailed report was not provided, LifeLabs did not demonstrate that it fully investigated the breach or adopted appropriate preventative measures.”[13] Two weeks later, on June 25, 2020, the privacy commissioners in Ontario and BC published a short summary of their combined investigation.[14]

In late 2019, the first of several class-action lawsuits was initiated in British Columbia. The case filed on December 30 at the Supreme Court of British Columbia claimed that LifeLabs had breached the statutory privacy rights as set out in the Canadian Personal Information Protection and Electronics Documents Act (PIPEDA). In the first three months of 2020, at least ten lawsuits were filed against LifeLabs in British Columbia and Ontario.

LifeLabs Responded to the Lawsuit and Considered a Possible Settlement

Throughout 2020 and 2021, the various lawsuits were consolidated until finally, one national action was confirmed, representing plaintiffs and class members from all jurisdictions. The amended statement of claim[15] was filed and published on February 3, 2022, and the certification hearing was scheduled for March 2 and 3, 2023, in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice.

The statement of claim relied on research prepared by the three privacy commissioners and published by the Saskatchewan Privacy Commissioner. In the statement of claim, the plaintiff stated that the security breach began in November of 2018 and possibly earlier. The security breach “continued undetected for at least a year before LifeLabs discovered it in or about late October 2019” (p. 15)[16]. During that one year, the cyber attackers accessed the personal information of LifeLabs’ customers and exfiltrated that information.

The statement of claim identified at least ten deficiencies in the technical and procedural safeguards at LifeLabs, including unencrypted or weakly encrypted personal information, failing to use network segmentation and segregation, failing to install security patches and other software updates, etc.[17] The statement of claim also stated that LifeLabs had drafted IT security procedure documents but had not finalized or brought the procedures into effect until May of 2020, several months after the discovery of the security breach.

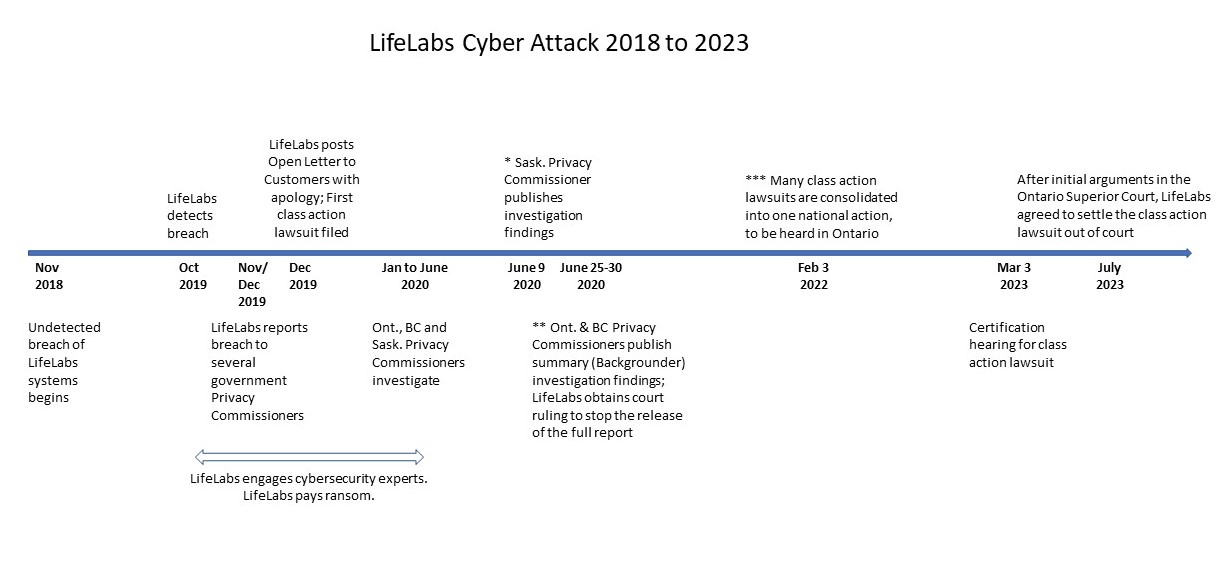

Figure 3 – Summary Timeline of the LifeLabs Cyber Attack outlines the timeline for the LifeLabs cyber attack. The reference documents that provided much of the data for the timeline are listed with the figure.

In preparation for the scheduled hearing, both parties completed cross examination of each other’s witnesses and prepared documents for the court, summarizing the facts. Three documents were filed with the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, as follows:

- On January 16, 2023, the plaintiffs filed a 92-page “Factum of the Plaintiffs for Certification.”

- On February 17, 2023, LifeLabs submitted an 83-page “Factum of the Defendants, Responding to the Certification Motion.”

- On February 27, 2023, the plaintiffs filed a 25-page “Reply Factum.”

These 200 pages of facts, supported by sworn affidavits of key witnesses, provided new information about the cyber attack. Although the case had not been heard, and the full details may never be published if an agreement were reached between the two parties, the evidence and arguments provided in the three factums provided insight into the cyber attack and its potential impact. The sections below summarize the three factums.

A. Factum for the Plaintiffs (January 16, 2023)

- Highly confidential test results for 131,957 LifeLabs customers were exfiltrated by the cyber attackers, for a period of approximately one year (p. 1).

- Personal information, including provincial health card information, for at least 8.8 million customers was also exfiltrated. (p. 1)

- The factum later notes, “LifeLabs cannot confirm that this is all that was accessed of exfiltrated” (p. 7).

- “Much of the data was unencrypted, making it highly vulnerable to theft and exploitation” (p. 2).

- When LifeLabs hired security experts on October 28, 2019, they discovered that cybercriminal “hackers had been lurking, undetected, in LifeLabs’ computers for almost a year” (p. 4).

- LifeLabs paid a ransom to the cybercriminals and received five datasets of client information; however, as the factum notes, “LifeLabs is unable to confirm that the cybercriminals deleted all versions of the data … it cannot confirm that the cyber-criminals have not provided copies of some or all of the stolen data to other criminal actors.” (p. 5).

- To further establish this point, the plaintiff factum argued the following: “It is simply not reasonable to believe that criminals permanently deleted the information and that they never sold or will sell it. LifeLabs’ trust in the assurances it purchased from the criminals is contrary to the basic and common-sense adage that there is no honour among thieves” (p. 17).

B. Factum of the Defendants, Responding to the Certification Motion. (February 17, 2023)

- LifeLabs confirmed that it received a ransom email on October 31, 2019, and following negotiations, the ransom was paid. The ransom amount was not disclosed. Nor did LifeLabs indicate if an insurance policy paid any portion of the ransom. The factum states: “The Cyber Attacker returned the data via an encrypted share link and stated that they did not retain any copies” (p. 2).

- LifeLabs agreed that it was true that “LifeLabs cannot state ‘with any certainty’ whether all of the stolen data was returned; cannot prove that none of the data was passed on to other criminals; and cannot prove that none of the data was for sale.” However, LifeLabs then asserted that “none of that is relevant” (p. 9).

- As their last statement of fact, LifeLabs noted: “Since the Cyber Attack, LifeLabs has not been approached by any person purporting to possess any of the stolen data, or by any customer presenting credible evidence of either an economic loss or an emotional or psychological impairment arising out of misuse by any criminal of the stolen data” (p. 10).

C. Plaintiff’s Reply Factum (February 27, 2023)

- Although the cyber attacker undertook to erase the stolen data, “one cannot rely on the word of a thief. LifeLabs admitted it has no proof that the data was erased” (p. 1).

- “The plaintiff’s experts unanimously agreed that the compromised data is often chopped up and sold in parts to maximize value.” LifeLabs’ assertion that the stolen data have not been found ignores this (p. 2).

The Ontario Superior Court hearing scheduled for March 2 to 3, 2023, was suspended on March 1 for this reason: “The parties agreed to adjourn this hearing pending the finalization of a potential settlement between the plaintiffs and defendants. If the potential settlement is finalized, it will require Court approval before it takes effect.”[18]

The “Dirty Hands” Dilemma

LifeLabs decided to pay the ransom. LifeLabs reported the incident to the provincial privacy commissioners as required by law. LifeLabs also communicated with its customers and took protective action. For a large and reputable company, these decisions seemed appropriate.

Lifelabs paid ransom on the expectation that criminals would follow through with their commitments. The class action lawsuit contended that criminals cannot be trusted and suggested that the private client data may still be available.Making a decision in this type of situation was sometimes referred to as the “dirty hands” moral dilemma.

The Factum for the Plaintiffs indicated that LifeLabs’ cybersecurity protection and procedures were weak or non-existent, with much of the data unencrypted. The stolen customer data included sensitive private medical information and financial information such as insurance accounts and credit card data. The attackers had almost one year of unchallenged access to the LifeLabs systems.

Making a decision in this type of situation was sometimes referred to as the “dirty hands” moral dilemma, where any decision would include moral problems.[19] One would have to get one’s hands dirty to solve the problem; there was no simple, clean solution.

LifeLabs senior management faced a difficult decision: Was it ethical and appropriate to pay ransom in a cyber attack? CEO Charles Brown had joined LifeLabs one year earlier, in 2018. Board Chair Jon Hantho had been in his position for less than a year. Responding to the ransomware attack was a critical decision for the new leaders and for all members of the senior executive team. LifeLabs’ reputation and trust with clients and the community were at stake.

Senior executives at LifeLabs weighed several issues in making the decision about whether or not to pay the ransom:

- If the ransom was paid, would there be any guarantee that the attackers would not ask for additional ransom?

- By paying the ransom—an action that would become publicly known—would the organization encourage other criminals to attempt similar attacks either at this company or similar organizations?

- Should LifeLabs have followed the advice of cybersecurity experts, legal experts, and law enforcement?

- Would the LifeLabs insurance coverage pay for some or all the ransom expense, and what would be the impact on insurance for future cyber attacks?

- What was the likelihood that the criminals would follow through on their threat if the ransom was not paid?

- How would LifeLabs’ stakeholders (e.g., owners, employees, customers, governments) react when they learned that LifeLabs had paid the ransom?

The Case Continued

In October 2023, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice approved the settlement reached in July 2023 between LifeLabs and the plaintiffs. KPMG was given the role of administering the claims and published a website where potentially over 8 million individuals could have submitted a claim. In the settlement agreement, which was available on the KPMG site, Lifelabs agreed to pay up to $9.8 million in settlement funds. The total amount paid would depend on the number of claims made. The settlement agreement identified the maximum amount that could be paid to each claimant was $150.

LifeLabs continued to operate as a successful enterprise. Lifelabs implemented additional cybersecurity measures in 2020. Public attention after the attack identified cyber vulnerabilities and the need for constant surveillance. In May of 2023, the chief information security officer (CISO) at LifeLabs was recognized for his leadership and commitment to innovation and secure services by the CIO Association of Canada as the Member of the Year. Ultimately, Lifelabs paid both the cybercriminals and the plaintiffs as a consequence of the firm’s weak cybersecurity strategy and invested internally in implementing additional cybersecurity measures to prevent future cybersecurity breaches. Did Lifelabs manage this cybersecurity breach well? Could they have managed it differently? What would you have done if you were President and CEO Charles Brown or Chair of the Board of Directors Jon Hantho and responsible for managing this cybersecurity crisis?

Exhibits

Figure 1 – Annual Number of Ransomware Attacks Worldwide

Source: Based on data from Petrosyan, A. (2023, August 31). Number of ransomware attempts per year 2022. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/494947/ransomware-attempts-per-year-worldwide/

Figure 2 – What Happened When Ransom Was Paid?

Source: Based on data from Petrosyan, A. (2023, April 13) Consequences of ransomware attacks for organizations following ransom payments worldwide in 2022. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1147471/outcomes-organizations-ransom-payments-it-professionals/.

Figure 3 – Summary Timeline of the LifeLabs Cyber Attack

Source: Created by the author.

Figure 3 Notes:

* June 9, 2020, Investigation Report on LifeLabs LP and Saskatchewan Health Authority [opens a PDF], Office of the Saskatchewan Information and Privacy Commissioner, https://oipc.sk.ca/assets/hipa-investigation-398-2019-399-2019-417-2019-005-2020-019-2020-021-2020.pdf

** June 25, 2020, Backgrounder: LifeLabs failed to protect personal information in 2019 breach [opens a PDF], Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario and Information and Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia, https://www.ipc.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2020-06-25-lifelabs-backgrounder-on-bc.pdf

*** February 2022, Statement of Claim, Justice Belobaba, Ontario Superior Court of Justice [opens a PDF], https://waddellphillips.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/LifeLabs-Fresh-as-Amended-Statement-of-Claim.pdf

References

Beamish, B. & McEvoy, M. (2019, December 17). Statement from the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario and the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia on LifeLabs privacy breach [opens a PDF]. www.ipc.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/2019-12-ipc_oipc-media-statement-final.pdf.

Carter v Lifelabs, 2022 Sup Ct J (Statement of Claim, February 9 [opens a PDF]). Retrieved from https://waddellphillips.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/LifeLabs-Fresh-as-Amended-Statement-of-Claim.pdf

Gartner Inc. (2021, July 12). Board briefing: Protection against cyber extortion and ransomware. p.7. https://www.gartner.com/en/documents/4003480

Grimes, R. A. (2021). Ransomware protection playbook. Wiley.

Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario. (2020, June 25). Ontario IPC and BC OIPC find LifeLabs failed to protect personal information in 2019 breach [opens a PDF]. [Press Release]. https://www.ipc.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2020-06-25-lifelabs-backgrounder-on-bc.pdf

Kruzeniski, R.J. (2020, June 9). Investigation report 398-2019, 399-2019, 417-2019, 005-2020, 019-2020, 021-2020: LifeLabs LP [opens a PDF]. Saskatchewan Health Authority. Office of the Saskatchewan Information and Privacy Commissioner. https://oipc.sk.ca/assets/hipa-investigation-398-2019-399-2019-417-2019-005-2020-019-2020-021-2020.pdf

LifeLabs. (2019, December 17). LifeLabs releases open letter to customers following cyber-attack. [Press release]. https://www.lifelabs.com/lifelabs-releases-open-letter-to-customers-following-cyber-attack/

LifeLabs. (n.d.). Customer notice: Cyber protections. https://customernotice.lifelabs.com/cyber-protections/

Nick, C. (2021). Dirty hands and moral conflict – lessons from the philosophy of evil. Philosophia, 50, 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-021-00385-9

Petrosyan, A. (2023, April 13). Consequences of ransomware attacks for organizations following ransom payments worldwide in 2022. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1147471/outcomes-organizations-ransom-payments-it-professionals/

Petrosyan, A. (2023, August 31). Number of ransomware attempts per year 2022. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/494947/ransomware-attempts-per-year-worldwide/

Sehgal, P. (2020, June 16). Six months after cyberattack, LifeLabs introduces CISO and new security policies: IT world Canada news. IT World Canada. https://www.itworldcanada.com/article/six-months-after-cyberattack-lifelabs-introduces-ciso-and-new-security-policies/432119

Sharton, B. R. (2021, June 2). Ransomware attacks are spiking. Is your company prepared? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/05/ransomware-attacks-are-spiking-is-your-company-prepared

Waddell Phillips. (2023). LifeLabs privacy class action. https://waddellphillips.ca/class-actions/lifelabs-class-action/

Image Descriptions

Figure 1

A bar graph with year on the x-axis and the number of cyber attacks on the y-axis.

- 2019 is 187.9 million cyber attacks

- 2020 is 304.6 million cyber attacks

- 2021 is 623.3 million cyber attacks

- 2022 is 493.3 million cyber attacks

An arrow above the 2019 bar slopes up to the 2021 bar and is labelled 333% growth.

Figure 2

A pie chart shows the following data:

- Paid ransom once and regained access to data = 52%

- Paid ransom and additional demands and regained access to data = 51%

- Refused to pay additional ransom demands, data was not recovered = 6%

- Paid ransom and data was not recovered = 1%

Figure 3

A timeline of the LifeLabs cyber attack includes the following information:

| Date | Action |

| November 2018 | Undetected breach of LifeLabs systems begins. |

| October 2019 | LifeLabs detects breach |

| October 2019 to June 2020 | LifeLabs engages cybersecurity experts; LifeLabs pays ransom. |

| November & December 2019 | LifeLabs reports breach to several government Privacy Commissioners. |

| December 2019 | LifeLabs posts Open Letter to Customers with apology; First class action lawsuit filed. |

| January to June 2020 | Ont., BC, and Sask. Privacy Commissioners investigate. |

| June 9, 2020 | Saskatchewan Privacy Commissioner publishes investigation findings (See Note 1). |

| June 25 to 30, 2020 | Ontario and BC Privacy Commissioners publish summary (backgrounder) investigation findings (See Note 2); LifeLabs obtains court ruling to stop the release of the full report. |

| February 3, 2022 | Many class action lawsuits are consolidated into one national action, to be heard in Ontario (See Note 3). |

| March 3, 2022 | Certification hearing for class action lawsuit. |

| July 2023 | After initial arguments in the Ontario Superior Court, LifeLabs agreed to settle the class action lawsuit out of court. |

Note 1: June 9, 2020, Investigation Report on LifeLabs LP and Saskatchewan Health Authority [opens a PDF], Office of the Saskatchewan Information and Privacy Commissioner, https://oipc.sk.ca/assets/hipa-investigation-398-2019-399-2019-417-2019-005-2020-019-2020-021-2020.pdf

Note 2: June 25, 2020, Backgrounder: LifeLabs failed to protect personal information in 2019 breach [opens a PDF], Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario and Information and Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia, https://www.ipc.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2020-06-25-lifelabs-backgrounder-on-bc.pdf

Note 3: February 2022, Statement of Claim, Justice Belobaba, Ontario Superior Court of Justice [opens a PDF], https://waddellphillips.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/LifeLabs-Fresh-as-Amended-Statement-of-Claim.pdf

[back]

Download a PDF copy of this case [PDF].

Read the Instructor’s Manual Abstract for this case.

How to cite this case: Babin, R. (2023). LifeLabs: The ethics of responding to a ransomware cyber attack. Open Access Teaching Case Journal, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.58067/7wmc-gv65

The Open Access Teaching Case Journal is a peer-reviewed, free to use, free to publish, open educational resource (OER) published with the support of the Conestoga College School of Business and the Case Research Development Program and is aligned with the school’s UN PRME objectives. Visit the OATCJ website [new tab] to learn more about how to submit a case or become a reviewer.

- Beamish & McEnvoy, 2019. ↵

- LifeLabs, 2019. ↵

- See Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario website. ↵

- Gartner Inc, 2021, p. 7 ↵

- For example, see Sharton, 2021. ↵

- Petrosyan, 2023, April 13 ↵

- Gartner Inc, 2021, p. 7 ↵

- Grimes, 2021. ↵

- LifeLabs, n.d. ↵

- LifeLabs, 2019. ↵

- Sehgal, 2020. ↵

- Kruzeniski, 2020. ↵

- Kruzeniski, 2020, p. 1. ↵

- Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario, 2020. ↵

- Carter v LifeLabs, 2022. ↵

- Carter v LifeLabs, 2022. ↵

- See page 16 of the statement of claim on the law firm's website for the full list of the deficiencies. ↵

- Waddell Phillips, 2023. ↵

- Nick, 2021. ↵