Vol. 2, No. 1 (June 2024)

Fuxin Mining Machinery Inc.: Time to Reshape for the Future

Lifeng Geng

All figures in Canadian dollars unless otherwise noted.

On July 18, 2022, Peter Li and his girlfriend Gloria Chu departed Canada from Toronto Pearson Airport and landed at Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport in China. Embarking on this trip was not an easy decision. After spending four years in the undergraduate business program and two years in the MBA program at a famous Canadian university, Li had worked for four years in the commercial mortgage department at a large Canadian bank. He loved his life in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and was enjoying his successful career in the fast-growing commercial mortgage business in Canada. Nevertheless, his parents were aging, and their family business, Fuxin Mining Machinery Inc. (FMMI) (located in Fuxin, Liaoning province in the northeast region of China), was at a critical turning point, requiring Li to make a major decision regarding his future involvement in the family business.

The Early Years

In early 1983, Li’s parents borrowed $8,000 from relatives and friends and purchased ownership of a small state-owned, street corner hardware mill. The mill had six employees, generated less than $40,000 in annual sales, and was at the brink of bankruptcy. Li’s parents worked day and night for the next 39 years, turning the mill into a successful family business with annual sales that exceeded $358 million in 2021. The family business improved their life and paid for Li’s education in Canada.

Profit from the business also allowed Li’s parents to buy his first house when he was 19 years old and had just started his undergraduate business studies in Canada. This housing investment marked the commencement of Li’s interest in finance and real estate investment. Li’s attention was drawn to the booming real estate market in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) in Canada. During his business studies, Li spent his free time attending open houses and studying the GTA’s real estate market, while his peer students were focusing on studying and working part-time jobs. In 2014, Li purchased another property using the proceeds from refinancing his first property. The snowball effect continued and by 2021 he had amassed a portfolio of seven condominiums, townhomes, and single-family homes in the GTA. Li’s successful venture into real estate investment influenced his decision to pursue a major in finance, subsequently leading him to embark on a career in the commercial mortgage industry following the completion of his MBA.

Li Senior

Li’s father, Li Senior, had not received any formal management or business training. Li Sr. managed the family business primarily based on his experience and entrepreneurial instinct. This approach was smooth and successful at the beginning. However, as the family business experienced rapid expansion, Li Sr. encountered challenges due to the increasing breadth of administrative tasks. He realized that he had too many responsibilities and it was growing increasingly difficult to manage all the businesses. This situation was exacerbated by the sudden eruption of a novel coronavirus in late 2019. The challenges presented by what became the COVID-19 pandemic escalated the pressure associated with overseeing the operations of the family business in China, resulting in disruptions and confusion across scheduling, supply chain management, labour recruitment, and other functional areas. The rules imposed during COVID-19 caused significant supply chain and delivery issues. The delivery truck drivers often could not get off the highway to deliver products for FMMI, even when they were only three kilometres away from the destination, if the truck had passed by a small town enroute that had one reported case of COVID. Hundreds of employees often woke up in the morning, surprised to learn that they were under quarantine and could not leave their apartment buildings. Foreign clients panicked that their flights would be cancelled, or visas would not be processed in time to make necessary business trips. The phone kept ringing, day and night, sometimes at 3:00 in the morning. The pandemic regulations and resulting supply chain issues took a heavy toll on Li Sr.’s already poor health condition. With several chronic problems diagnosed, and a recent experience with high blood pressure, irregular heartbeat, and lost sleep, Li Sr. explained to his family that he was unsure whether he could survive the pandemic and worried about the future of their family business. Li Sr. expressed desperation when chatting with his son. On a WeChat video call, he urged Li to “Come home!”

Li Junior

Born after China had adopted the one-child policy, Li was his parents’ only child. He had two grandparents on his father’s side, and two grandparents on his mother’s side. Therefore, Li had six seniors in his family to take care of. His girlfriend, Gloria Chu, was in a similar situation. Before the pandemic, the couple visited families back in China twice every year, as travelling between Toronto, Canada, and Beijing, China, was easy and convenient. The pandemic made travelling nearly impossible because of strict COVID-19 testing policies, the unpredictable difficulties in securing health certificates from the consulate, as well as frequent cancellations of flights. Because of the declaration of the pandemic in 2020, Li and his girlfriend had been unable to visit their families for almost three years.

After several months of struggle and many long discussions, Li and Chu finally decided that Li should wrap up his real estate investment business in the GTA, quit the banking job he loved, and travel back to China to manage his family’s business. According to China’s zero-incident policy, upon landing in Guangzhou, Li and Chu were required to spend one week at a quarantine hotel in Guangzhou, then one week at a quarantine hotel in their hometown, which was followed by another week of self-quarantine at their home. While excited and exhausted in their quarantine hotel room, Li finally found himself a big chunk of free time to carefully review the information he had received from his father regarding the state of the family business. He had to develop a plan regarding the future direction of the family business and present it to his father upon returning home. Li had fourteen days to prepare a recommended business strategy to best manage the growing family business.

History of Growth

Li’s hometown was Fuxin, Liaoning province in the Northeast region of China. With a population of 1.93 million, Fuxin once had one of the largest coal mining operations in the country. In early 1983, Li’s parents took over a small, bankrupt, state-owned street corner hardware mill. At the time, the mill manufactured simple hand tools like hammers, screwdrivers, wrenches, etc. The Li family turned the mill into a profitable business within the same year. Hardworking and riding on China’s economic boom, the Li family rapidly expanded their business and in 1991, they reached the benchmark of $10 million in sales and made a profit of $3.81 million. Then, there came a wave of bankruptcies of state-owned enterprises in the 1990s. Millions of workers who had secured jobs in the state-owned enterprises suddenly became unemployed.[1] The mid-1990s was the darkest era for the heavy industry-loaded Northeast region of China. To stop the losing stream of money and secure new jobs for the laid off workers, local Chinese governments were desperate and eager to find people who were willing to take over the bankrupt, state-owned firms. They were willing to sell the bankrupt firms at cheap prices – sometimes even free!

Based on what they had heard from friends and business associates in the economically prosperous southern coastal areas, Li’s parents knew that the economic boom had generated an insatiable appetite for raw materials such as coal, iron, steel, copper, and lead. For example, coal priced at $6 a ton mined out at Fuxin could easily be sold for $70 a ton in Shanghai. With their entrepreneurial instinct, Li’s parents believed that the insatiable appetite for raw materials would soon convert to vast demand for mining tools and equipment. In 1996, the Li family purchased a bankrupt pneumatic mining tools/equipment factory for approximately $1 million. This was a good deal, as the replacement cost for the land, factory building, machinery tools, and inventory surpassed $100 million. The same year, the family business received its name, Fuxin Mining Machinery Inc. (FMMI). This name was still in use in 2022 when Li made his journey home.

In 1998, FMMI bought another bankrupt electric mining tools/equipment factory. This was the start of a series of acquisitions and expansions. These acquisitions helped the Li family turn a small street corner hardware mill into a small conglomerate that offered a wide array of mining tools/equipment, ranging from hand hammer, pneumatic mining tools/equipment, electric mining tools/equipment, wheeled equipment, tract equipment, belt transporters, dozers, pulverizers, grinders, and accessories/parts. By 2022, FMMI had operations in the Northeast, Northwest, Southwest, and other major interior mining provinces like Shanxi, Henan, Jiangxi, and Shandong. FMMI owned fifteen production facilities, five parts warehouses, two rebuild sites, and a display store for their finished products. Under FMMI’s umbrella were also four stand-alone companies: FMMI Steel, FMMI Material, FMMI Transportation, and FMMI International. FMMI Steel’s business was to process standardized steel or waste iron/steel that it bought from the market to meet the specifications required for its tools and machinery. The output mainly served FMMI’s needs, with the remaining output sold to external clients. Sales to external clients roughly accounted for 32% of FMMI Steel’s revenue. FMMI Material encompassed a diverse array of materials, including aluminum, titanium, plastics, and more. FMMI Material processed the materials that it bought from the open market further so that they could be used for manufacturing mining machinery or tools. FMMI Material also served external clients, which represented 37% of its annual sales. FMMI Transportation provided transportation and delivery services for FMMI and external clients. The transportation business was divided about 52% to 48% between FMMI and its external clients. This split offered an efficient way to utilize FMMI’s fleet, for example, by making a delivery for FMMI and then loading external clients’ cargo for the return trip, or vice versa.

FMMI International served overseas clients and exported FMMI’s products (mainly hand tools, parts, and accessories). FMMI International’s sales accounted for less than 6% of FMMI’s total sales in 2021. A small proportion of FMMI International’s business was to import special materials and components (e.g., control chips) that FMMI could not procure from domestic suppliers.

Positioning of FMMI

With $358 million in annual sales and more than 10,000 employees, FMMI was a large private firm in China. However, FMMI was still a small player in China’s $10.7 billion mining equipment market.[2] From the beginning, Li’s parents chose not to compete head on with the giant players like Caterpillar, XCMG, Sany, Zoomlion, and CITIC Heavy Industry. These big players had tens of billions of dollars in annual sales and manufactured giant mining equipment, such as 200-tonne excavators, 810-ton mining trucks, and 16,125-tonne hydraulic excavators.[3][4][5][6][7] These companies served huge state-owned mining operations like China National Coal Group’s Pingshuo surface coal mining operation. This state-owned mine had an accumulated investment of $64.9 billion and produced 70 to 80 million tons of coal annually.

FMMI focused on a niche market by providing accessories, parts, and customized small-sized tools/equipment that could be used in small, privately owned mines that were difficult for the big pieces of equipment to enter or maneuver. Although targeting the niche market, FMMI never compromised in quality or customer service. The company had a reputation for a “Gold Standard” when it came to their product quality and customer service. Their customer service protocol ensured that their service personnel would be onsite within 24 hours following a report of any incidents.

Organization of FMMI

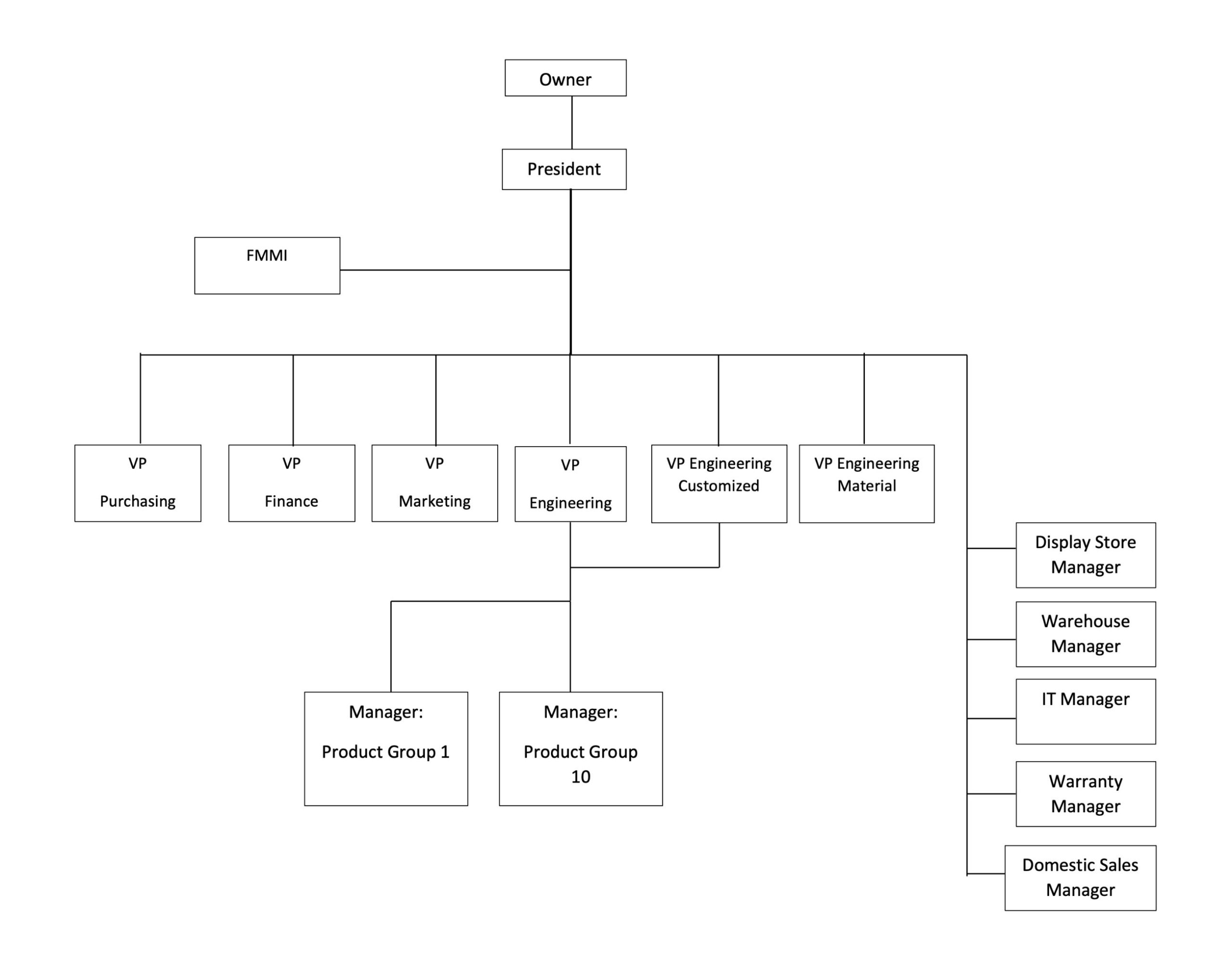

As FMMI experienced significant growth, Li’s parents adopted an organic and informal approach to its organizational structure. They expanded the company gradually by incorporating additional plants, product lines, or newly acquired business units into the existing company structure, one at a time. Executives were mainly promoted internally, and Guoqiang Zhao, one of the six original employees when Li’s parents took over the small mill, had been promoted to the position of FMMI’s president. Over the years, Zhao had proven to be hardworking and loyal, with an insightful entrepreneurial focus. Like Li Sr., Zhao lacked formal training in management, and he oversaw most, but not all, of FMMI’s operations. As illustrated by Exhibit 1 – FMMI’s Organization Chart, FMMI had eleven functional areas (departments): purchasing, finance, marketing, engineering, engineering (customized systems), engineering (material processing), IT, warehouse, warranty, domestic sales, and display store. These eleven functional areas or departments either had VPs or managers, and all of them reported to Zhao. FMMI had fifteen manufacturing sites and two rebuild sites. Manufacturing sites one to five had VPs overseeing their operations. Manufacturing sites six to fifteen and the two rebuild sites had plant managers instead. The VPs for manufacturing sites one to five, the plant managers for the two rebuild sites, and the remaining ten manufacturing sites reported to the owner.

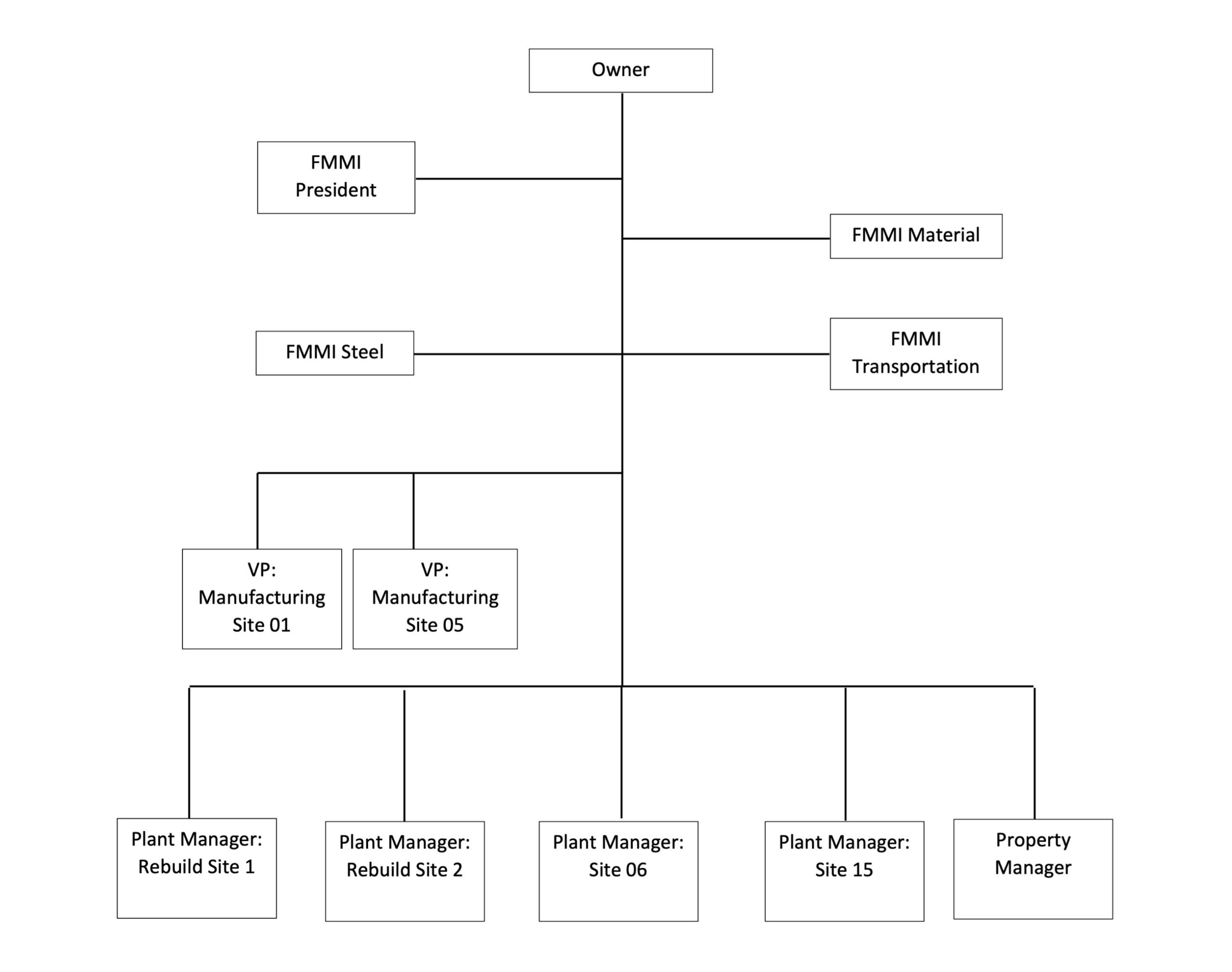

Three of the four stand-alone companies, FMMI Material, FMMI Steel, and FMMI Transportation reported to the owner, and FMMI International reported to the president. See Exhibit 2 – FMMI Organization Structure.

FMMI also had ten product groups. The managers of these ten product groups reported to both VP Engineering and VP Engineering: Customized Systems. In addition, FMMI had a property manager, who oversaw the management and maintenance of all FMMI properties and reported directly to the owner.

Back to Quarantine Hotel Strategic Reflection

Li meticulously reviewed the information he received from his father regarding the family business and identified two primary concerns that demanded his attention. The first concern pertained to FMMI’s organizational structure, wherein an excessive number of managers reported directly to the owner. As illustrated in Exhibit 1, FMMI’s president, three stand-alone companies, five VPs of the manufacturing sites, plant managers at ten manufacturing and two rebuild sites, and even the property manager, all reported to Li Sr. directly.

The second area of concern lay in FMMI’s distinctive accounting practices. Unlike conventional setups, FMMI lacked a dedicated accounting department; instead, accountants were spread across its individual manufacturing sites and reported to the VP of finance. Moreover, the company did not employ standardized performance metrics but relied on a uniform measurement of cost — specifically the ratio of manufacturing cost to product weight. Accounting reports revealed significant variations, with some plants and product lines achieving a manufacturing cost as low as $5.00/kg, while others incurring costs that exceeded $11.50/kg. Upon conducting preliminary analyses, Li discovered that while the majority of sites were profitable, certain manufacturing facilities were operating at a loss. Additionally, there appeared to be a deficiency in mechanisms linking manufacturing costs and financial outcomes to employee and executive incentives, such as bonuses and promotions.

During his hotel quarantine, Li conducted several extensive telephone meetings with his father, where Li Sr. explained, “this is the way things had been done in FMMI for the past 39 years.” During these conversations, Li Sr. articulated a longstanding operational approach spanning nearly four decades, wherein he assumed the predominant decision-making role and organizational leadership. For example, in instances of labour shortages at manufacturing sites or inter-unit conflicts, he was the person who orchestrated resolutions by interfacing directly with unit managers. He personally oversaw the allocation of bonuses and promotions based on his firsthand observations and discretionary judgment. Li Sr. acknowledged that while this approach had worked historically, as business grew, he found himself spread thin across his various administrative duties and he was becoming overwhelmed with too much on his shoulders. He realized a long time ago that changes needed to be made, but he did not know how or where to start. Ultimately, Li Sr. conveyed a sense of relief during the telephone meetings regarding his son Li Jr.’s return, viewing his son’s professional training, education, experience, and managerial acumen as pivotal resources for steering FMMI toward a promising trajectory.

Li Jr.’s Dilemma

Li had developed an affinity for the relaxed lifestyle common in Toronto. Having received a quality education from a renowned Canadian business school, he subsequently garnered four years of professional experience within a commercial mortgage division of a prominent Canadian banking institution. His typical workday adhered to a set schedule, commencing at 8:30 a.m. and concluding at 4:30 p.m., punctuated by two coffee breaks and one lunch break. Everything was done, every decision was made, following clearly specified procedures and established protocols. Li recognized a disparity between his personal managerial style and the managerial approach adopted by his father. Li did not think that he could live his life and manage FMMI like his father did because he desired a better work–life balance and did not want to work 12-hour days and have to pick up the phone at 3 a.m. Consequently, he realized that he was facing a pivotal juncture for both himself and FMMI — a turning point to shape his own life and to shape FMMI for the future. This dilemma prompted Li to contemplate how to navigate this transition without replicating his father’s managerial style. Central to this deliberation was the formulation of strategies to enhance FMMI’s future management efficacy. Within the limited time frame of his fourteen-day quarantine before his return home, Li needed to devise a comprehensive plan to present to his father to effectuate these changes. Where should he start?

Exhibits

Exhibit 1 – FMMI’s Organization Chart

[back]

Exhibit 2 – FMMI’s Organization Structure

[back]

Image Descriptions

Exhibit 1 – FMMI’s Organization Chart

This flow chart begins with owner at the top, flowing down to president. Below president is a row of vice presidents. Branching to the left before the row of VPs is FMMI International. The row of VPs includes VP purchasing, VP finance, VP marketing, VP engineering, VP engineering customized systems, and VP engineering material processing. On the right side, the row branches into a vertical row which includes the display store manager, warehouse manager, IT manager, warranty manager, and domestic sales manager. The VP engineering and VP engineering customized systems box are connected with a horizontal line, which flows vertically to both manager: product group 1 on the left and manager: product group 10.

[back]

Exhibit 2 – FMMI’s Organization Structure

This flow chart begins with owner at the top and a vertical line flowing down. Branching below and to the left from this line is FMMI President. Then below and to the right from the line is FMMI Material. Below, FMMI Steel branches off on the left and FMMI Transportation branches off on the right. The vertical line ends in a horizontal line, from which branches the VP: manufacturing site 01 and VP: manufacturing site 05 on the left side and a vertical line on the right. At the end of the vertical line is a horizontal row with the following: plant manager rebuild site 1, plant manager rebuild site 2, plant manager site 06, plant manager site 15, and property manager.

[back]

References

Caterpillar. (2022). 2021 annual report. CM20220429-5abae-1adc1 (scene7.com).

CITIC Heavy Industry. (2022). 中信重工机械股份有限公司 2021 年年度报告 [PDF] [CITIC Heavy Industries Machinery Co., Ltd. 2021 Annual Report].

Huajing Institute of Industry. (2020). Report on China’s mining machinery industry and forecast for 2020-2025, Report No. 610077, Beijing, China. Huajing Institute of Industry.

Li, P. (1998). Solutions for unemployment at old industrial bases: Investigation with nine large state-owned enterprises in northeast region. Sociology Studies, (4), 3–15.

Sany Group. (2022). 三一重工股份有限公司 2021 年年度报告 [PDF]. [Sany Heavy Industry Co., Ltd. 2021 Annual Report]

XCMG (2022). 徐工集团工程机械股份有限公司 2021 年度报告 [PDF] [XCMG Construction Machinery Co., Ltd. 2021 Annual Report].

Zoomlion. (2023). Zoomlion Heavy Industry Science and Technology Co., Ltd. 2022 annual report [PDF].

Download a PDF copy of this case [PDF].

Read the Instructor’s Manual Abstract for this case.

How to cite this case: Geng, L. (2024). Fuxin Mining Machinery Inc.: Time to reshape for the future. Open Access Teaching Case Journal, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.58067/h0zw-7546

The Open Access Teaching Case Journal is a peer-reviewed, free to use, free to publish, open educational resource (OER) published with the support of the Conestoga College School of Business and the Case Research Development Program and is aligned with the school’s UN PRME objectives. Visit the OATCJ website [new tab] to learn more about how to submit a case or become a reviewer.

ISSN 2818-2030