Vol. 2, No. 2 (December 2024)

The Role of Teacher Agency: Challenges Implementing an ICT Initiative in Education in India

Glenda S. Stump; Meera Chandran; Omkar Balli; and Punam Medh

Gopika Jadav was a program lead at the Connected Learning Initiative (CLIx), an award-winning action research program for implementing information and communication technology (ICT) innovations in education. CLIx was implemented in 461 schools with approximately 2000 teachers across the four Indian states of Chhattisgarh, Mizoram, Rajasthan, and Telangana from 2015 to 2019. After the successful implementation of CLIx Phase I in these four states, the CLIx project team recommended scaling the innovation, expanding it to additional schools in Phase II. All four states had expressed an interest in the expansion, yet officials were wary of challenges related to scaling. One key challenge was that state teachers were, in their view, slow or resistant to innovations. State officials wondered whether a new group of teachers would willingly adopt the technology required for successful implementation during a second phase. It was well recognized that the response of teachers was of prime importance in efforts toward school improvement or school reform.[1] However, there was a contradiction in the way teachers were regarded in the Indian context; they were respected as a guru in one instance and labelled as unskilled, even unprofessional, in another.[2]

Jadav’s challenge was to develop a compelling argument to convince state officials that teachers did indeed demonstrate agency and willingness to adopt technology innovations in the successful CLIx Phase I, and that teacher agency played a key role in this success. To move forward to CLIx Phase II, this innovation had to be adopted by the state and integrated into the school ecosystem. Jadav needed to dislodge officials’ preconceived notions regarding teachers in India and persuade them to recognize teachers as agents capable of enacting pedagogic change and adopting new innovations, thereby providing the needed support for the success of CLIx Phase II. State support for teacher agency was critical for the scaling and success of Phase II as additional schools would become part of the program and the states would assume a greater role in implementation.

As Jadav walked back to her desk after a long workday, she wondered how she should approach this challenge ─ what information she should analyze from Phase I, what evidence she should provide to justify her position, and how she should present her recommendation to state officials to convince them that teachers did indeed demonstrate agency during Phase 1. Jadav knew that if she was not successful in her mission, the state would not approve the expansion of CLIx in a Phase II or, alternatively, they might approve the expansion without recognizing and supporting teachers’ agency in its implementation. In either case, many schools would be denied the opportunity or the benefits provided by the initiative in the next phase of the project. Where should she start?

Gopika Jadav, Program Lead, CLIx

In her career spanning 20 years Jadav worked on various projects with Indian state governments and with the federal Ministry of Human Resource Development before becoming an integral part of CLIx. She had a sharp understanding of how the states functioned and their proclivity, not just for any data, but for specific kinds of data that provided evidence for decision making. This insight helped Jadav to guide CLIx throughout its formative years.

Jadav and her team of field resource coordinators had spent considerable time and effort trying to convince state officials that Phase I would not have been successful without teachers’ initiative and contribution. By the end of Phase I, the project team had overcome some of the early infrastructure and teacher capacity challenges, which enabled further adoption of the project through teacher buy-in. Jadav recognized that the ongoing support provided by the CLIx project team played an important role in the development of teacher agency during Phase I and that in Phase II, this supportive school ecosystem would need to be nurtured by the state. The problem that Jadav faced was that even though the success of CLIx Phase I relied upon teacher agency for success, she could not identify a direct way to measure and provide evidence for it.

Context/Background

The school system in India is the second largest in the world, with 264 million students and 9.68 million teachers in 1.51 million schools, of which two-thirds are government-operated. Schooling in India is free and compulsory for children from the age of 6-14, and the government school system has made major progress in the last decade in ensuring universal access to elementary education. Despite growth in private schooling, government schools are the main provider of schooling for the majority of students, particularly those from less privileged backgrounds and students in rural and underserved communities (see Figure 1 – Typical Classrooms in Government Schools). Government schools face severe resource constraints in terms of school infrastructure and provisioning for trained teachers. In line with the National Policy on Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in School Education,[3] government schools were to be provided ICT labs, each with a minimum of 10 networked computers to encourage integration of technology in school education. However, the actual provisioning of computer systems and their optimal usage is varied across the states.

Teachers in government schools in an Indian context occupy a low status in the hierarchy of the government school system. The literature supports this view, from a historical perspective[4] as well as from the perspective of recent shifts in the political economy of education[5] occurring in the Indian school system. These shifts subject teachers in government schools to a discourse of efficiency that pits government schools in competition with private schools, which are seen as producing better learning outcomes. The efficiency argument fails to account for the scale of the government school system, which provides for a large number of students from marginalized groups.[6] Secondary-level teachers in government schools have strong identities as subject teachers and are professionally qualified and experienced in their work.

CLIx Innovation

The main purpose of the CLIx innovation was to supplement classroom learning with carefully designed technology-based modules in the areas of mathematics, science, communicative English, and digital literacy. The online modules were accompanied by written resources for teachers as well as students.[7] The modules were built on the foundation of “pedagogic pillars,” or principles of needs-based design to enhance engagement and learning effectiveness. These pillars—collaborative learning, authentic learning, and learning from mistakes—guided the use of contemporary technology and online capabilities to engage students and to make learning effective. CLIx recognized the role and involvement of teachers in pedagogic transformation and therefore emphasized teacher professional development (TPD) to inform teachers regarding the use and benefits of technology innovations. The TPD was intended to empower teachers by providing useful knowledge and instruction regarding pedagogy, as well as the tools involved in the CLIx innovation and thus, went beyond the mere imposition of ICT in schools.

The overall aim of this innovation project was to introduce technology-based learning in state-run schools along with a student-centred pedagogy, which was counter to the more traditional pedagogies used in government schools. While this idea itself was not unique, CLIx was different and ambitious, as it envisioned this innovation at scale, aiming at students in higher grades—8th, 9th, and 10th—in 461 schools across four states with approximately 2000 teachers.

Given the central role of teachers in this innovation, an important challenge was the socio-cultural and techno-pedagogical diversity of the teachers. The four CLIx states represent diverse geographical regions, Chhattisgarh in Central India, Mizoram in the Northeast, Rajasthan in the Northwest, and Telangana in the South, with teachers from diverse linguistic, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds. Given the socio-political histories of these states, there were considerable variations in their educational systems, state leadership and administrative systems, regulations regarding teacher education, recruitment policies, professional development opportunities, working conditions, academic timelines, school infrastructure, and curriculum. For example, secondary school teachers in Telangana benefited from robust in-service professional development compared to teachers in the remaining three states. Teachers in Mizoram and Rajasthan were older and were in regular employment, whereas in Chhattisgarh, teachers were relatively younger and more likely to be under contractual employment. The number of teachers teaching “out of field,” (i.e., without a graduate degree in the subjects they taught) was highest in the case of English language compared to mathematics and science. Most importantly, teachers’ ability to use ICT varied considerably both across and within each of the states.

Like teachers, students who participated in CLIx were diverse across the four geographic regions. Although they were similar in terms of their family’s less privileged backgrounds, students were diverse in terms of their linguistic ability, access to technology, and ICT skills. In government schools, English grammar was taught as a subject for only one period per day and the remainder of the day’s instruction was done in the local language; thus, students had limited proficiency in speaking or understanding when English was used as the language of instruction. Although some students had limited forms of technology in their homes, many students had the opportunity to engage with it only in the school setting.

CLIx was designed to be an action research project to work directly with the diverse demographics involved in the program. Researchers aimed to gather data from multiple streams of ongoing CLIx activities in a cycle of planning, implementing, observing, and learning about the impact of action taken as the CLIx curriculum was implemented within the participating schools.

The 3-Year CLIx Journey

The Planning and Development Phase – Year 1

CLIx Year 1 (2016–2017) was about planning the innovation, putting together teams and resources, and initiating the development of the technology-based modules. The year kicked off with the selection of CLIx intervention schools. The selection process was based on participation in the government’s ICT@School scheme[8] wherein each school would have a minimum of 10 computers. An infrastructure mapping study was conducted in potential participating schools to understand the nature and status of the ICT infrastructure available. The results of this study showed that the condition of ICT infrastructure varied considerably from state to state. In all, 101 schools in Rajasthan, 30 schools in Chhattisgarh, 30 schools in Mizoram, and 300 schools in Telangana were selected for implementation of the CLIx intervention. The computer labs of selected intervention schools were prepared by repairing the existing machines.

In addition, various teams were put in place. Table 1 presents a summary of the teams and their activities.

Table 1 – CLIx Teams and Functions

| Teams | # Members | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Curriculum team | 15 | Initiated the design and development of student modules/resources. |

| TPD team | 15 | Created and implemented teacher training workshops to support student modules for mathematics, science, communicative English, and ICT. |

| Technology team | 15 | Developed student and teacher platforms on which modules would be delivered. Also supported the development of technology tools such as simulations. |

| Field teams | 35 | Ensured readiness of school computer labs, supplied technical and academic support to teachers, and liaised with state and district officials for implementation of the innovation. |

| Research team | 10 | Developed protocols along with data collection instruments to assess and evaluate the processes and outcomes of CLIx. |

Teacher Intervention − TPD Workshops

The TPD team designed specific interventions to facilitate the development of teachers’ agency for implementation of CLIx modules. They designed and conducted face-to-face workshops to develop a culture where teachers’ ideas, values, and beliefs about ICT could be openly shared with peers. In those workshops, the TPD team also introduced CLIx student modules to familiarize teachers with the learning objectives and intended pedagogy. Many teachers did not have prior knowledge of ICT, so beginner level exercises were a part of the TPD design, which helped them learn and gain confidence. However, teachers were not introduced to all the CLIx student modules during the face-to-face workshops due to time constraints and because some of the initial modules were still under development at the time of training.

Teachers’ Response to TPD Workshops

Analysis of post-workshop survey data revealed that teachers found TPD workshops to be interactive, engaging, and a space where they could share their ideas and raise concerns about CLIx, (e.g., [what they liked most] “Learning through [a] collaborative approach; helpful and co-operative nature of team members;” “We exchanged our ideas with the workshop group. This is what I liked most;” “This workshop was completely different from previous trainings. Participants were openly expressing their difficulties. In response, facilitators gave answers with correct examples and in a very co-operative way…”).[9] Even though the teachers enjoyed and appreciated the workshops far more than they did most of their regular professional development training, they seemed to harbour a few apprehensions. For example, they articulated that CLIx content was limited to only a few topics and required a lot more class time than they normally spent on the same topics in their regular schedule. They also raised concerns about the often failing lab infrastructure and about class sizes being too large to fit into the computer labs at one time (e.g., “276 students in class, poor student to computers ratio. Periods of maths teachers are held at the same time, availability of lab [is] a concern.”).

Teachers’ Actions Post TPD Workshops

Following the training, teachers were often unable to practise or implement the modules because their school labs had been unused and in poor condition. The lack of adequate time for practise with new technology-enabled content and the time lag between training and actual module implementation together resulted in teacher frustration. Many teachers still attempted to integrate the modules into their curriculum. Table 2 presents the number of schools that implemented at least one module for students during the first year.

Although three states showed high tryouts, one state clearly lagged. Upon investigation into the low numbers in Telangana, field team members found that teachers articulated difficulty in accommodating CLIx modules in their existing teaching schedule, as the classes were not formally added to the schools’ timetables (daily schedule). Additionally, many teachers articulated a lack of confidence to implement CLIx modules after a training workshop of just a few days. Many of them expressed reservations about their ability to tackle the technical aspects of teaching with ICT.

Table 2 – States With at Least One Module Implementation During Year 1

| State | Participating CLIx schools | CLIX schools implementing in Year 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Rajasthan (RJ) | 101 | 81 (80%) |

| Chhattisgarh (CG) | 30 | 24 (80%) |

| Mizoram (MZ) | 30 | 28 (93%) |

| Telangana (TS) | 300 | 14 (5%) |

The Development and Implementation Phase − Year 2

In Year 2 (2017−2018), additional student modules were developed. To ensure access to the student resources, local server machines and additional peripherals such as headphones and splitters were provided to schools in three of the four states. A new platform to host CLIx modules was developed and made available in all intervention schools. The field teams discussed the goals of the CLIx curriculum with state officials, who then decided to integrate CLIx classes into the school timetables.

Teacher Intervention – Introducing the RTICT Program

The TPD team conceptualized, designed, and launched a post-graduate certificate program called Reflective Teaching with Information Communications and Technology (RTICT) aimed at bolstering teacher involvement and engagement. The program was meant to motivate and support teachers after the learnings from Year 1. RTICT was a blended program that included coursework completed on an online platform hosted by the local university and face-to-face workshops that gave teachers hands-on experience with CLIx modules, serving as exemplars of technology-enabled, student-centred pedagogy. The RTICT program also had a community of practice (CoP) component hosted on Telegram, an instant messaging application. To promote sustainability and a local context for the training, teacher educators (TEs) were identified in each of the states. The TEs were provided with professional development training to support teacher training and the rollout of the RTICT program.

Participation in RTICT

A large number of teachers (1828) across four states enrolled in the first RTICT online course. They also attended the 112 in-person workshops, which were the face-to-face component of the program. Teachers articulated appreciation for the interactive nature of this component because they were familiar and comfortable with the workshop format. The face-to-face component then became part of the state-mandated teachers’ professional development and teacher feedback indicated that they appreciated this change. While the average teacher attendance in the face-to-face component was reasonably high (75%), only 3.32% of the participants obtained the required grades to complete the online course component. One possible reason for the low completion was that the online RTICT courses themselves were not state-mandated and offered via a mode that teachers were less familiar with.

Although teachers did not engage fully with the RTICT courses, they did become active in their CoPs. In their domain-specific Telegram groups, the nature of teachers’ interactions changed; instead of posting messages containing only social greetings, they began to post more messages and photos containing their thoughts about pedagogy and CLIx implementation.

Teachers’ Actions Post TPD

Whereas 147 schools implemented at least one CLIx module in Year 1, 252 schools did the same in Year 2. The main reason given for non-implementation was a lack of infrastructure in the school labs. In response to this, Jadav’s team, in collaboration with the research team, developed an implementation monitoring tool (IMT) to track availability of infrastructure, teachers’ concerns, and resultant support. Field team members completed a digital version of the IMT on their cell phones each time they visited a school. The tool consisted of eight sections collecting information that was static (e.g., school name and location) as well as dynamic (e.g., lab functionality on the day of the visit). Table 3 presents the focus of each section and provides examples of related questions.

Analysis of data from the IMT revealed that some teachers were still uncomfortable rolling out the modules independently. They also faced platform issues, such as unsuccessful loading of assessments, failed translation of certain modules, and malfunctioning features of customized tools. As the field team observed that technical glitches were impeding teachers’ motivation to implement digital activities, the team made multiple visits to participating schools, focusing on supporting teachers as they learned to navigate and troubleshoot the platform.

Table 3 – Implementation Monitoring Tool Summary

| Section/Focus | Example Questions |

|---|---|

| Preliminary information | Which state is the school located in?

Date & Time |

| Lab functionality | Is the CLIx platform functioning? (Y/N) Are there at least ten computers in the lab? (Y/N)(If N) What is the total number of computers in the lab?Are all computers functioning (Functionality = working computer, and related components except headphones & splitters)? (Y/N)(If N) How many computers are not functional? |

| Module implementation prior to visit | Are the CLIx classes included in the school timetable?

Is there a designated person from the school who manages the computer lab? (Y/N) (If Y) Who does this? (e.g., headmaster, teacher, etc.) Which science/mathematics/English modules have been implemented prior to this visit? Reasons for not implementing any science/mathematics/English modules in the school Did the teacher complete all units of the science/mathematics/English modules named above? (If N) How much did they complete? |

| TPD | Which of the following teachers attended the F2F workshop this year?

Which of the following teachers actively view and create posts on a mobile chat application, (e.g. Telegram, WhatsApp)? Which of the following teachers have interacted with the TEs through Telegram/any other mode in the last 15 days? |

| Module implementation at time of visit | On the day of the visit, was a session observed? (Y/N)

Which module was observed? |

| Student observations | Were the pairs/groups of students discussing the modules? (Y, at least 50% of the students for 50% of the class time/N)

Were the pairs/groups of students helping other groups? (Y, at least 50% of the students/N) Did students use the local language to communicate with each other? (Y/N) Did the students use the workbook? |

| Teacher observations | Did the teacher use batching to make sure all students have access to the lab? (Y/N/NA)

Was the teacher present to conduct the entire CLIx lab session? (Y/N) How did the teacher begin the class? What did the teacher do during the CLIx lab session? |

| Teacher/headmaster concerns; observer impressions | What are the teachers’ questions/concerns regarding the module? (Please record in teacher’s words)

What are the headmaster’s concerns regarding the use of ICT for teaching? (Please record in headmaster’s words) What is going well in the roll out process? (Your impressions) What needs attention? (Your impressions) |

The Phasing Out Year/Adoption Year – Year 3

By Year 3 (2018 –19), most of the platform issues from the previous years had been addressed. Eighty percent of the participating schools had included CLIx sessions in their school timetables. Schools with large class sizes created small student lab batches[10] to ensure that all students had access to the ICT lab. An increasing number of teachers became comfortable with the CLIx online platform and were able to troubleshoot basic technical issues on their own. Table 4 presents the number of schools that rolled out different student modules during Year 3. Each school typically had at least one teacher per subject (English/mathematics/science) for implementation.

No additional modules were developed during Year 3. For continuous professional development of teachers, the post-graduate RTICT program became modular and optional, wherein teachers could select one or more courses and complete the program within five years. Different pathways for programs that met teachers’ short-term goals were offered to encourage their engagement.

During Year 3, a larger, more systemic issue began affecting CLIx implementation. A large number of teacher transfers occurred, particularly in two states—Rajasthan and Telangana—leaving fewer teachers trained to implement CLIx modules. This turn of events required extensive efforts to train the new teachers.

In addition to the high number of teacher transfers, Telangana continued to suffer from poor infrastructure in many schools. Only 150 of the 300 selected schools had between 70% and 100% functionality of the computer lab, which limited teachers’ implementation of the modules despite their completion of the training program. The computer labs in schools in the other three states were in reasonably good condition by this time, as the schools were able to develop an infrastructure that was supportive of module implementation.

Table 4 – Number of Schools that Implemented Modules by Year

| Year | Rajasthan (RJ) | Chhattisgarh (CG) | Mizoram (MZ) | Telangana (TS) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1: 2016–17 | 81 | 24 | 28 | 14 | 147 |

| Year 2: 2017–18 | 100 | 28 | 28 | 96 | 252 |

| Year 3: 2018–19 | 101 | 28 | 30 | 96 | 255 |

Findings from CLIx Phase 1 Research

The final year of CLIx was an intense phase of module rollout after critical conditions such as functional ICT labs, related infrastructure, access to CLIx resources, trained teachers, and effective school-based support for implementation were deemed to be in place. CLIx field personnel provided school-based support on an average of five visits per school for 82% of schools. In 91% of the school visits, servers were functioning, peripherals such as headphones were available, and computers were functioning throughout the academic year. Power did not pose an issue for 75% to 85% of the cases. Nearly all software and platform-related issues were resolved, hardware issues were reduced from the previous year, TPD attendance was moderate to high, and teachers had access to smartphones to participate in online CoPs.[11]

It was under the above conditions that teachers, the key actors in the schools, were positioned to make normative judgements about the value of using CLIx modules to teach their respective subjects. Teachers made practical judgements about determining the topics to be implemented, managing student batching for optimal use of the ICT lab, and engaging students in the lab through meaningful pedagogic processes, etc.

In the final academic year of implementation, data were collected via lab and class observations, surveys, and the CLIx platform. Lab observations were recorded on the implementation monitoring tool (IMT) during field visits to schools. Information on student usage of modules was also derived from the IMT observations, as well as from the CLIx digital student platform that captured data on unique user logins for each module. Teacher surveys provided information related to their concerns about CLIx implementation, self-efficacy for digital skills, beliefs about use of ICT, and attitudes toward ICT-based teaching. Last but not least, data were obtained via qualitative observations of teachers during their implementation of CLIx modules in their respective schools.

CLIx Teachers’ Changing Beliefs and Values

CLIx teachers’ response to surveys conducted at the beginning of CLIx (baseline survey) and at the three-year mark (endline survey) included their self-reported ICT skills, beliefs about use and effects of ICT, perceptions regarding the challenges of integrating ICT in their teaching, and their pedagogic practices. Given the large-scale transfers that occurred in two states, there were only 162 teachers across the four states for whom survey responses were available from both the baseline and endline surveys. This group was designated as a panel, and their baseline–endline responses were compared to determine any change in self-reported ICT skills, beliefs, and perceptions over the time they were a part of CLIx

ICT Skills

The panel teachers reported statistically significant improvement in their own ICT skills from baseline to endline in two respects: “Advanced digital skills,” which improved by 0.35 points (on a 1-5 Likert-type scale) and “Online ICT engagement,” which improved by 0.21 points (on a 1-4 Likert-type scale). There was a decline in reported basic ICT skills (-0.10), but this was not statistically significant. This decrease in perceived basic skills was surprising to those who conducted the TPD workshops because they noted teachers’ basic ICT skills to be very low to begin with. However, teachers may have overestimated their basic skills in the baseline survey, only to develop a more realistic view after they were introduced to new forms of edtech in the trainings. Table 5 describes the attributes of the three factors that were assessed in the surveys.

When the panel group was categorized based on the extent of their TPD, it was found that 76 out of 162 teachers (47%) who had received the full three years of TPD reported significant improvement in their advanced digital skills (0.33 points) and online ICT engagement (0.25 points). This group also reported a non-significant decline in basic ICT skills (-0.06).

Table 5 – Attributes of Factors Assessed by Survey

| Factors | Attributes |

|---|---|

| Basic ICT skills | Ability to start a computer; handle a mouse device; save files; use word-processing software, spreadsheets; type in English, type in Hindi, Telugu, Mizo |

| Advanced ICT skills | Ability to download/upload files; photograph and record audio/video clips on phone/digital camera; use online maps, simulations; download and use apps on mobile phone; use video conferencing; program |

| Online ICT engagement | Experience of searching internet for personal or professional work; experience of interacting with online community |

Source: CLIx Research Team, 2020, p. 31. Credit: Adapted from Table 5.1 in Making EdTech Work for Secondary School Students & Their Teachers [PDF], © TISS, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Beliefs About Teaching With ICT

The panel teacher group reported a slight decline (-0.02 points) in their positive beliefs regarding use of ICT for teaching. Their perception of challenges in accessing computers and training, as well as problems with devices, power, and internet access, remained the same or declined slightly over time (0 and -0.02 respectively), whereas their perception of extrinsic challenges with respect to teaching with computers showed a statistically significant increase (0.20).

The subgroup of panel teachers with full TPD also reported lower positive belief (-0.03) about the value of teaching with ICT in the endline compared to baseline, despite their increase in skills. On the one hand, their perception of challenges in accessing computers and training, as well as problems with devices, power, and internet access was non-significant and similar to the entire group (-0.14 and -0.09 respectively). On the other hand, they reported a lower increase than the entire group in extrinsic challenges of teaching with computers (0.09). Taken together, these findings suggest that although these teachers reported an increase in advanced skills and perceived ICT implementation as less challenging than their peers, they were still uncertain of its pedagogical value.

Teachers’ Perceptions of CLIx

From a macro perspective, conditions for CLIx module implementations were favourable in terms of lab infrastructure, availability of modules and resources, extent of TPD provided to teachers, and regular school-based visits with support by CLIx field personnel. However, from a micro perspective at the individual or school level, the accommodation of CLIx in the everyday school schedule was a different matter. Qualitative data revealed teachers’ views regarding CLIx implementation in their classrooms.

Teacher Concerns

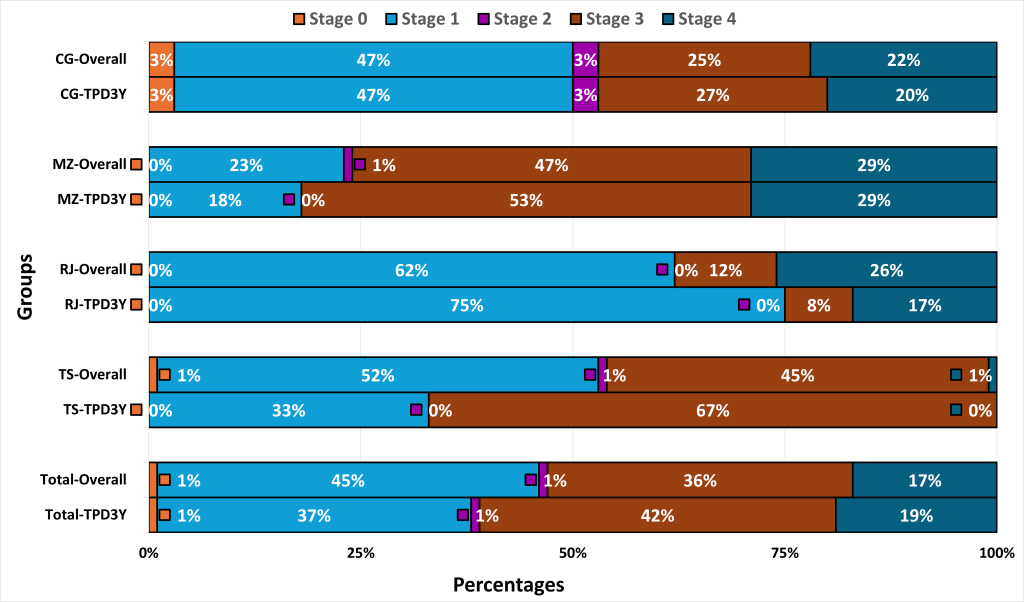

In the endline survey, teachers’ responses to an open-ended survey question point to their concerns regarding CLIx implementation. These responses (N=273) were coded using the Stages of Concern (SoC) from the Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM)[12] which describes seven categories of possible concerns experienced by individuals as they encounter an innovation (see Table 6).

Results showed that most teachers (45.4%) were in Stage 1, the Informational Stage, in which concerns pertain to knowing more about the innovation. A high percentage of teachers (35.9%) were in Stage 3, the Management Stage, in which concerns pertain to more practical issues such as managing large class sizes, batching students for ICT lab, etc. A small percentage of teachers (16.8%) articulated concerns that mapped onto Stage 4, the Consequences Stage, in which concerns pertain to consequences of the program for their students’ learning.

When compared with stages of concern for all teachers who completed the endline survey, 19% of the panel teachers who received three years of TPD articulated concerns in Stage 4 as compared to 17% in the entire group.

As shown in Figure 2, there was a high percentage of teachers whose concerns revolved around either gaining more information about the innovation (Stage 1) or managing the day-to-day aspects of implementing it in their classrooms (Stage 3). (See Figure 2 – Comparison of Stages Between All CLIx Teachers and Those with 3 Yrs of TPD)

Table 6 – Number of Teachers by Stage in Each State

| Stages of concern | CG | MZ | RJ | TS | Total | Stage total as % of total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 0 (unconcerned) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0.7% |

| Stage 1 (informational) | 17 | 17 | 36 | 54 | 124 | 45.4% |

| Stage 2 (personal) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1% |

| Stage 3 (management) | 9 | 35 | 7 | 47 | 98 | 35.9% |

| Stage 4 (consequences) | 8 | 22 | 15 | 1 | 46 | 16.8% |

| Total | 36 | 75 | 58 | 104 | 273 | 100% |

Source: CLIx Research Team, 2020, p. 26. Credit: Table 4.3 in Making EdTech Work for Secondary School Students & Their Teachers [PDF], © TISS, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Factors That Promoted or Impeded CLIx Adoption/Implementation

Interviews with a small group of teachers across the states provided in-depth insights into their perceptions about factors that impacted the adoption and implementation of CLIx. Box 1 presents the factors that the teachers described.

Box 1 – Reported Factors That Impacted Clix Adoption/Implementation

Promoted adoption/implementation of CLIx:

- Teacher professional development that was practise-based. TPD provided clarity on CLIx student module content and understanding of optimal module implementation.

- CLIx field teams’ school-based support. CLIx teams were accessible as well as successful at getting labs fixed and running smoothly.

- Quality of the student module content. Modules provided students with clear conceptual understanding using pedagogy that encouraged active participation.

Impeded adoption/implementation of CLIx:

- Lab infrastructure and low computer-to-student ratio in schools with high class size. Managing the large class size and engaging students who could not be accommodated in the labs at the same time as their classmates was inhibiting from an operational perspective.

- Coverage of select topics in the syllabus through CLIx ICT-based pedagogy while the rest of the topics were taught in the conventional mode provided dissimilar coverage of topics.

- CLIx module content was not always relevant to their required school curriculum. The required curriculum had to be completed within a specified time frame, leaving less room for ICT-based innovation.

Source: Based on CLIx Research Team (2020, p. 51).

Teachers’ Implementation of CLIx and Pedagogical Practice

Teacher pedagogical practices varied based on individual and institutional factors prevalent in the given contexts. The IMT data provided a glimpse of the extent and quality of teacher initiative and engagement in the CLIx module rollout as recorded during school visits by field teams as part of school-based support across the four states. Teachers’ own accounts of their pedagogical practices were available from the endline survey data, and lab observations made by CLIx research associates during the endline provided an additional perspective.

Teacher Engagement in CLIx Rollout

During initial rollouts, teachers were sometimes obligated to respond to other administrative duties; in those cases, CLIx field personnel oversaw the students. Teachers were present in the lab for the entire session in 71% of the 500 lab observations recorded from 255 schools. When present for the entire session, teachers actively engaged in pedagogical processes and discussion with students in 73% of the cases. In 53% of those cases, they were observed initiating the discussion, while in the remaining 41% of the cases, they engaged with students only when they were called upon. In about 6% of the cases, they did not engage actively in any manner. As shown in Table 7, when teachers were in the lab for only part of the session, they did not engage in discussion with students most of the time (82%).

Table 7 −Teachers’ Use of Discussion in CLIx Labs

| Teacher engagement | Initiated discussion with entire lab | Did not initiate discussion with entire lab | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present for entire lab session (71%) | 73% | 27% | 354 |

| Not present for entire lab session (29%) | 18% | 82% | 146 |

Source: CLIx Research Team, 2020, p. 25. Credit: Adapted from Table 4.2 in Making EdTech Work for Secondary School Students & Their Teachers [PDF], © TISS, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Pedagogical Practices

Data for teachers’ pedagogical practices during CLIx implementation were obtained from observation of their regular classrooms as well as CLIx lab sessions. The observations were conducted to identify pedagogical principles constituted by the design of CLIx TPD and student module offerings. Data were also obtained via observations in classrooms of non-CLIx teachers for comparison.

Out of a total of 92 regular classroom observations (60 CLIx and 32 non-CLIx), CLIx teachers showed desired teacher behaviours, such as relating lesson content to real life and checking for students’ conceptual understanding. This finding occurred more frequently among CLIx teachers when compared to the non-CLIx teachers. However, there was still a relatively high percentage of CLIx teachers who never checked for conceptual knowledge, or encouraged students to speak during the observations. (See Table 8).

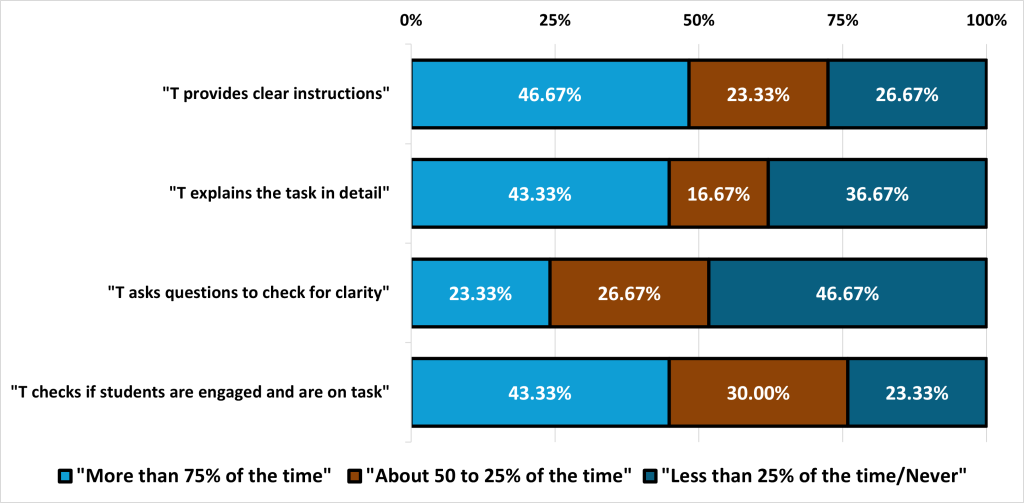

Figure 3 shows that a relatively high percentage of other desired behaviours were being practised by teachers over 75% of the lab time in 29 qualitative CLIx lab observations. (See Figure 3 – Teacher Behaviours During CLIx Lab Sessions by Duration.)

The desirable behaviours included teachers providing clear instructions to students regarding their activities (46.7%), explaining the task in detail (43.3%), and checking if students were engaged and on task (43.3%). There were comparatively fewer instances of teachers asking questions to check for clarity (23.3%).

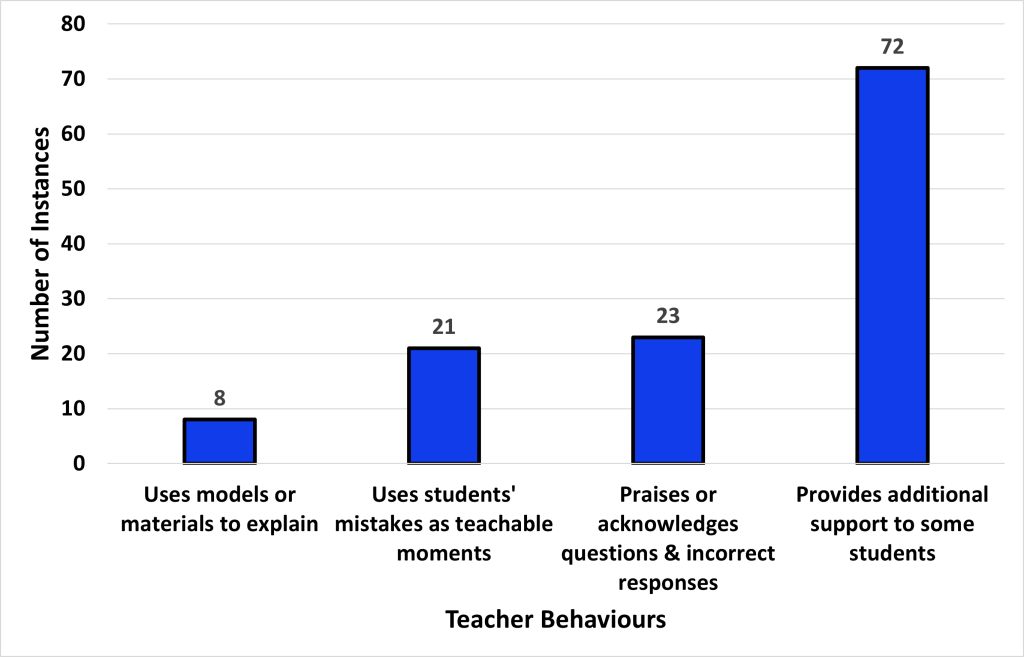

Frequency counts from CLIx lab observations (see Figure 4 – Teacher Behaviours During CLIx Lab Sessions by Frequency) also showed teachers providing additional support (72 instances), praising students and acknowledging their inputs (23 instances), and using students’ mistakes as teachable moments (21 instances).

Overall, teacher behaviours indicated more engagement with students when they were present in CLIx lab sessions for the entire duration. The qualitative analysis of CLIx lab sessions showed teachers exhibiting behaviours that served to reinforce student learning by ensuring they were clear about the task, remained on task, and learned from their mistakes. Additionally, as presented in Table 8, CLIx teachers showed a comparatively higher frequency of desired constructivist pedagogies compared to the non-CLIx teachers in their regular classroom teaching.

Table 8 − Teacher Behaviours in CLIx and non-CLIx Regular Classrooms

| Frequency of behaviours | Relating to real life | Checking conceptual knowledge | Getting students to speak | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLIx | Non-CLIx | CLIx | Non-CLIx | CLIx | Non-CLIx | |

| Frequently (> 5 times) | 48.4% | 15.6% | 22.6% | 12.5% | 16.13% | 18.8% |

| Occasionally (1–2 times) | 22.6% | 46.9% | 35.5% | 50% | 41.9% | 43.8% |

| Never | 29.0% | 37.5% | 41.9% | 37.5% | 41.9% | 37.5% |

| Total observations | 31 | 32 | 31 | 32 | 31 | 32 |

Note: Frequencies are reported as a percentage of observations.

Source: CLIx Research Team, 2020, p. 46. Credit: Adapted from Table 7.3 in Making EdTech Work for Secondary School Students & Their Teachers [PDF], © TISS, CC BY-SA 4.0.

The Dilemma

The state’s willingness to approve the expansion of CLIx into Phase II hinged on Jadav’s ability to develop a compelling recommendation with supporting data that demonstrated teacher agency in Phase I. This issue held significance not only because substantial effort and resources would be needed for teacher professional development in Phase II as the program expanded to additional schools, but also because the program’s success in the next phase was even more dependent on the teachers’ agency, as the states would assume a greater role in implementation.

Jadav needed to convince officials that teachers were critical to the implementation of the program. She needed to dislodge officials’ preconceived notions regarding teachers in India and persuade them to think of teachers as agents capable of enacting pedagogical change, thereby providing the needed support for the success of Phase II of CLIx. Jadav wondered how she should approach this problem, what evidence she should provide to justify her position, and how she could present her recommendation to convince state officials so that additional schools in these four states would have the opportunity to adopt and reap the benefits of the CLIx program and associated technology in Phase II. Where should she start?

Figures

Figure 1 – Typical Classrooms in Government Schools

Figure 2 – Comparison of Stages Between All CLIxTeachers and Those with 3 Yrs of TPD (N=273)

Note: Total number of respondents: Overall: CG-36, MZ-75, RJ-58, TS-104; TPD3Y: CG-30, MZ-34, RJ-12, TS-21

Source: CLIx Research Team, 2020, p. 26. Credit: Figure 4.4 in Making EdTech Work for Secondary School Students & Their Teachers [PDF], © TISS, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 3 – Teacher Behaviours During CLIx Lab Sessions by Duration

Source: CLIx Research Team, 2020, p. 48. Credit: Figure 7.3 in Making EdTech Work for Secondary School Students & Their Teachers [PDF], © TISS, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 4 – Teacher Behaviours During CLIx Lab Sessions by Frequency

Source: CLIx Research Team, 2020, p. 48. Credit: Figure 7.4 in Making EdTech Work for Secondary School Students & Their Teachers [PDF], © TISS, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Image Descriptions

Figure 1 – Typical Classrooms in Government Schools

Image A

The image shows a classroom filled with students who are sitting on the floor, with boys in the left foreground and girls in the right background. The students are mostly dressed in matching blue uniforms and are seated closely together in rows with bookbags in front. Some students have textbooks open in front of them, either in their laps or on their bags, and students are looking towards the front of the room, on the right side (not pictured), suggesting they are engaged in a lesson. The classroom walls are plain, with a blackboard visible on one side. There are two ceiling fans and windows in the background allow natural light to enter.

Image B

The image depicts a classroom scene with a group of female students seated at communal desks, with their backs to the camera. The students are wearing blue and white uniforms, and they are facing a blackboard at the front of the room. A student stands at the blackboard facing the class, possibly presenting. The classroom walls are pale and worn, adorned with several small posters or pictures near the ceiling above the blackboards. Backpacks are placed on the floor next to the desks. Natural light filters in from doors or windows on both sides of the room, casting shadows across the room.

Figure 2 – Comparison of Stages Between All CLIxTeachers and Those with 3 Yrs of TPD (N=273)

The image is a horizontal stacked bar chart comparing CG, MZ, RJ, TS, and Total. Each group has two rows, one labelled “Overall” and the other “TPD3Y.” The bars represent different stages (0 to 4), with corresponding colour codes: Stage 0 is orange, Stage 1 is light blue, Stage 2 is purple, Stage 3 is brown, and Stage 4 is dark blue. Each portion of the bar is labelled with a percentage, indicating the distribution of stages within each group. Percentages for each stage vary across the rows, showing how each category is divided. The data is included in the following table:

| Group | Stage 0 | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG – Overall | 3% | 47% | 3% | 25% | 22% |

| CG – TPD3Y | 3% | 47% | 3% | 27% | 20% |

| MZ – Overall | 0% | 23% | 1% | 47% | 29% |

| MZ – TPD3Y | 0% | 18% | 0% | 53% | 29% |

| RJ – Overall | 0% | 62% | 0% | 12% | 26% |

| RJ – TPD3Y | 0% | 75% | 0% | 8% | 17% |

| TS – Overall | 1% | 52% | 1% | 45% | 1% |

| TS – TPD3Y | 0% | 33% | 0% | 67% | 0% |

| Total – Overall | 1% | 45% | 1% | 36% | 17% |

| Total – TPD3Y | 1% | 37% | 1% | 42% | 19% |

Figure 3 – Teacher Behaviours During CLIx Lab Sessions by Duration

The image is a horizontal stacked bar chart illustrating the frequency of observed teacher behaviours. Each category has a horizontal bar divided into three segments. These segments are color-coded: blue for “More than 75% of the time,” brown for “About 50 – 25% of the time,” and dark blue for “Less than 25% of the time / Never.” The data conveyed in the graph is provided in the following table:

| Category of Behaviour | “More than 75% of the time” | “About 50 to 25% of the time” | “Less than 25% of the time/Never” |

| “T provides clear instructions” | 46.67% | 23.33% | 26.67% |

|---|---|---|---|

| “T explains the task in detail” | 43.33% | 16.67% | 36.67% |

| “T asks questions to check for clarity” | 23.33% | 26.67% | 46.67% |

| “T checks if students are engaged and are on task” | 43.33% | 30.00% | 23.33% |

Figure 4 – Teacher Behaviours During CLIx Lab Sessions by Frequency

The image is a bar chart representing various teacher behaviours and the number of instances they occur. The y-axis is labelled “Number of instances,” ranging from 0 to 80 in increments of 10. Four vertically oriented bars represent each behaviour, with heights corresponding to their respective values. The x-axis lists four different teacher behaviours. The bar values are as follows:

- Uses models or materials to explain = 8 instances

- Uses students’ mistakes as teachable moments = 21 instances

- Praises or acknowledges questions & incorrect responses = 23 instances

- Provides additional support to some students = 72 instances

References

CLIx Research Team. (2020). Making edtech work for secondary school students & their teachers: A report of research findings from CLIx Phase I [PDF]. Connected Learning Initiative. Tata Institute of Social Sciences.

George, A. A., Hall, G. E., & Stiegelbauer, S. M. (2006). Measuring implementation in schools: The Stages of Concern Questionnaire. Southeast Educational Development Laboratory.

Government of India (2012). National policy on information communication technology (ICT) in school education [PDF]. Ministry of Human Resource Development, India.

Kumar, K. (2005). Political agenda of education: A study of colonialist and nationalist ideas. SAGE Publications India.

Imants, J., & Van der Wal, M. M. (2020). A model of teacher agency in professional development and school reform. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 52(1), 1–14.

Mukhopadhyay, R., & Ali, S. (2020). Teachers as agents and policy actors: The NPM and an alternative imagination. Handbook of Education Systems in South Asia, 1–23.

Mukhopadhyay, R., & Sarangapani, P. M. (2018). Introduction: Education in India between the state and market–concepts framing the new discourse: Quality, efficiency, accountability. In School education in India, (pp. 1–27). Routledge India.

Sarangapani, P. M. (2020). A cultural view of teachers, pedagogy, and teacher education. In P. M. Sarangapani, R. Pappu (eds.), Handbook of education Systems in South Asia, (pp. 1–24). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3309-5_27-3

Attributions

Tables 5, 6, 7 & 8 and Figures 2, 3 & 4 are reused and/or adapted from Making EdTech Work for Secondary School Students & Their Teachers: Research Findings from CLIx Phase I, by the CLIx Research Team, Connected Learning Initiative, © 2020 by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, and licensed Creative Commons – Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International.

Download a PDF copy of this case [PDF].

Read the Instructor’s Manual Abstract for this case.

How to cite this case: Stump, G. S., Chandran, M., Balli, O. & Medh, P. (2024). The role of teacher agency: Challenges implementing an ICT initiative in education in India. Open Access Teaching Case Journal, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.58067/53ft-2w82

The Open Access Teaching Case Journal is a peer-reviewed, free to use, free to publish, open educational resource (OER) published with the support of the Conestoga College School of Business and the Case Research Development Program and is aligned with the school’s UN PRME objectives. Visit the OATCJ website [new tab] to learn more about how to submit a case or become a reviewer.

ISSN 2818-2030

- Imants & Van der Wall, 2020. ↵

- Sarangapani, 2020. ↵

- Government of India, 2012. ↵

- Kumar, 2005. ↵

- Mukhopadhyay & Ali 2020. ↵

- Mukhopadhyay & Sarangapani, 2018. ↵

- See the Connect Learning Initiative website for a list of modules. ↵

- Government of India, 2017. ↵

- CLIx Research Team, 2020, p. 20−22. ↵

- The average class sizes were over 40 students in grade 9 across CLIx schools, with some schools in CG and RJ having a maximum of 80-100 students. The lab size in all schools was the same, with not more than 10 systems. Sending students in smaller batches to the lab was a necessary strategy in these cases. ↵

- CLIx Research Team, 2020, pp. 54. ↵

- George et al., 2006. ↵