Vol. 2, No. 2 (December 2024)

Pipework Warehouse Inc.: Managing Disruptions in Supply and Demand

Fatih Yegul; Jane Gravill; and Juliet Conlon

All figures in Canadian dollars unless otherwise noted.

It was a Monday morning in late September 2021 when Troy Gilbert, Plumbing Category Manager at Pipework Warehouse Inc. (PWI), logged onto PWI’s enterprise resource planning (ERP) system sales module to check updates on customer orders and inventory levels in preparation for the day ahead. Gilbert was surprised to discover that the stock level for standard 3″ pipe—a commonly used product that PWI typically kept in stock for their top-tier customers—was close to zero. Gilbert knew that many of his regular top-tier customers would soon be placing their weekly orders for their construction projects and were likely to require the commonly used 3″ piping to continue their work. Unfortunately, PWI would not have sufficient supply on hand. Gilbert wondered whether regular customers would start searching elsewhere to source their products. Gilbert also knew that lead times from suppliers for high-demand items were long, and prices on replacement stock were increasing rapidly, causing challenges in setting their own sales prices.

Gilbert commented,

Our biggest concern was [companies] that we do not traditionally do business with going on to our website and basically ordering all our products, and the system would just process it through, and our logistics department overnight would ship it. And I wouldn’t know about it until in the morning when we realized we have nothing left on the shelves.

Gilbert was supposed to meet with the management team in a few days to offer them a summary of this situation. Gilbert needed to recommend a strategy to the management for how the company would respond to the frequent price hikes and manage their sales channels and inventory at a time of limited supplies while avoiding considerable damage to the top-tier customer service levels. The company relied upon these customers for regular sales. Gilbert resolved to spend some time organizing his understanding of the problem and generating a list of short- and long-term solutions.

Pipework Warehouse Inc.

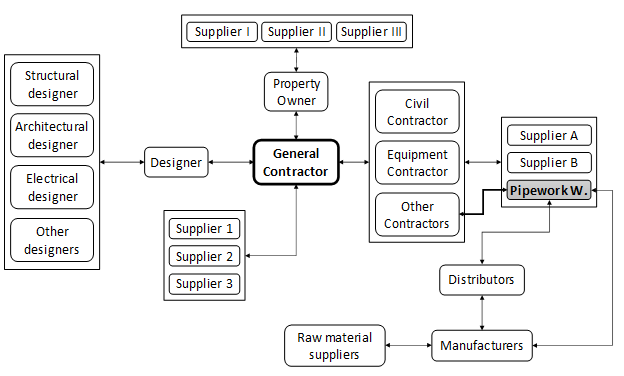

PWI was a wholesale distribution corporation established over 50 years ago and operated in the HVAC (heating, ventilation & air conditioning) and plumbing industry, which was worth $35.16 billion in 2019 with a growth rate of 9%[1]. The growth in this industry represented an opportunity for PWI to leverage its extensive industry knowledge and experience to expand and meet growing demands. PWI had 250 non-unionized employees located in nine wholesale branches, three luxury showrooms, and two distribution centres in southwestern Ontario. PWI distributed thousands of different products (SKUs)[2] primarily to customers in Southwestern Ontario. PWI supplied the items it sold from large North American distributors and manufacturers and imported some directly from overseas (Asian and European markets). The distributors stocked many imported items, and the manufacturers had to supply several raw materials from international markets. Thus, PWI conducted its business in a complex global construction supply network. See Exhibit 1 − Position of Pipework Warehouse Within the Construction Industry Supply Network.

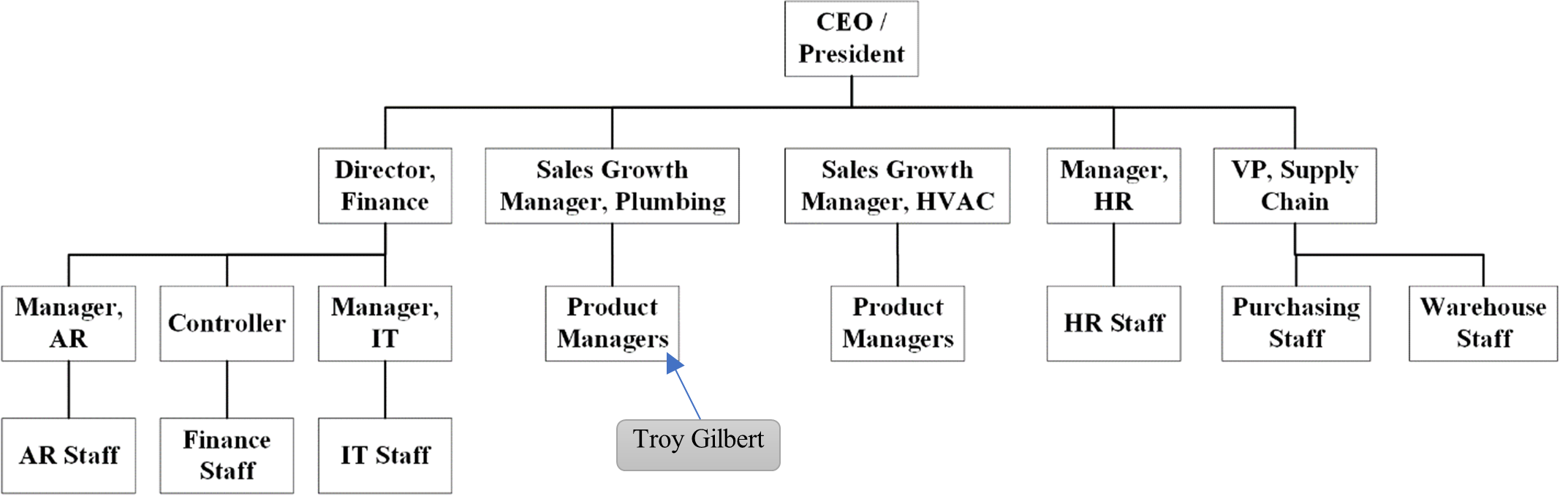

Gilbert had several decades of experience in the wholesale distribution business, mainly in the HVAC and plumbing industry. He worked for PWI for 22 years, the last 11 years of which he worked as the category manager, more specifically, product manager—plumbing. His primary responsibility was to oversee both the sales and supplies in this role. Gilbert needed to comprehend the demand patterns from the customers and ensure sufficient items were in stock to fulfill those demands, as PWI only sold products that were already available in stock in its warehouses. PWI’s organizational structure was flat. Gilbert reported to the sales growth manager—plumbing, who reported to the CEO. See Exhibit 2 − PWI Organization Chart.

Gilbert explained,

As category managers, it is non-stop; we are talking all day, every day with the sales managers. … Our goal is to grow sales, and … my primary concern is making sure what product we are going to have, who we are going to source it from, who is the vendor we want to partner with. … We serve the vendors, and we serve our customers as a wholesale distributor.

A Disrupted Supply Chain and Unanticipated Labour Shortages

With the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, the once-obscure concept of “supply chain,” something rarely contemplated by the public, became the focus of daily news headlines.[3] The supply chain’s sudden leap into public interest was attributed to widespread delays reported in the shipping container industry. The extreme backlogs observed across global containerized trade since 2020 made the anchoring of ships at the largest international ports, at times by lines measuring 80 vessels long, commonplace by winter 2021.[4] Backlogs experienced in the shipping industry had far-reaching repercussions that impacted wholesalers, manufacturers, distributors, and consumers with long wait times. With the shipping industry responsible for transporting approximately 90% of goods traded globally,[5] containerized goods on ships equated to items consumers use every day, from cement and fuel to computers and furniture.

Early in the pandemic, while few products saw temporary increases in demand (e.g., hygiene products[6] and computer hardware[7]), the demand for most products, including construction materials, plummeted for two months as many activities around the globe were halted.[8]

The uncertainty surrounding the emergence of COVID-19 in late 2019 left many experts expecting a downturn in trade. Anticipating a reduction in business, shipping firms idled 11% of their international fleet.[9] However, instead of a collapse in trade, import demand for consumer goods saw a surprising increase due to changes in consumption and shopping patterns after the pandemic was declared and shutdowns or lockdowns became common.[10] Lacking adequate time and planning to reposition empty containers to ports where they were needed, the shipping industry encountered a mismatch between supply and demand, resulting in empty containers in all the wrong places.[11]

Although the impact of COVID-19 explained much of the upheaval in the shipping industry, the pandemic was not the only culprit. A string of dramatic events further strained the shipping system, most notably, the blockage of the Suez Canal in March 2021 by the 400-metre ship the Ever Given. The six-day canal closure strained the shipping industry by delaying nearly 400 vessels from crossing between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea.[12] The August 2020 explosion at the port of Beirut in Lebanon,[13] a month-long labour dispute at Canada’s second-largest port in April 2021[14] and extreme weather[15] all made matters worse. Facing a steady pace of disruptions in 2020 and 2021, the shipping industry and the delays it encountered grabbed the world’s attention.

Workforce shortages further exacerbated business operations during this period. Speaking specifically about the construction industry, Heath Catt of the construction and design-build company Burns & McDonnell described the impact of labour shortages, claiming, “The trend is also taking its toll on suppliers and fabricators, affecting shop production levels and driving up the prices of manufactured equipment.”[16] Contributing to shortages were worksites with on-site COVID-19 outbreaks. One analysis of worksites experiencing COVID-19 outbreaks in Los Angeles County, California, found that most outbreaks occurred in manufacturing (26.4%).[17] In Vietnam, where thousands of factories were completely closed for periods of time during the pandemic, manufacturers struggled even months after reopening to reach production capacity, limited by 70% or less of their workforce in place.[18] Labour numbers from the United States indicated unmet demand for workers, with 2.2 million more job openings than unemployed workers in the economy as of September 2021.[19] With companies unable to reach full production capacity, it was no surprise when retailers and manufacturers reported that their inventories plunged.[20] Labour shortages added another layer to the multitude of disruptions brought on by the pandemic and disruptions of the production and supply chain processes in 2020 and 2021.

PWI’s Order Fulfillment Challenges

Businesses in many industries have survived unprecedented times since the onset of the pandemic, facing considerable fluctuations in demand and supply trajectories. PWI was impacted by these fluctuations and had to determine how to effectively manage the dynamic supply chain trends, customer expectations, employees, and relationships with business partners to keep the business afloat.

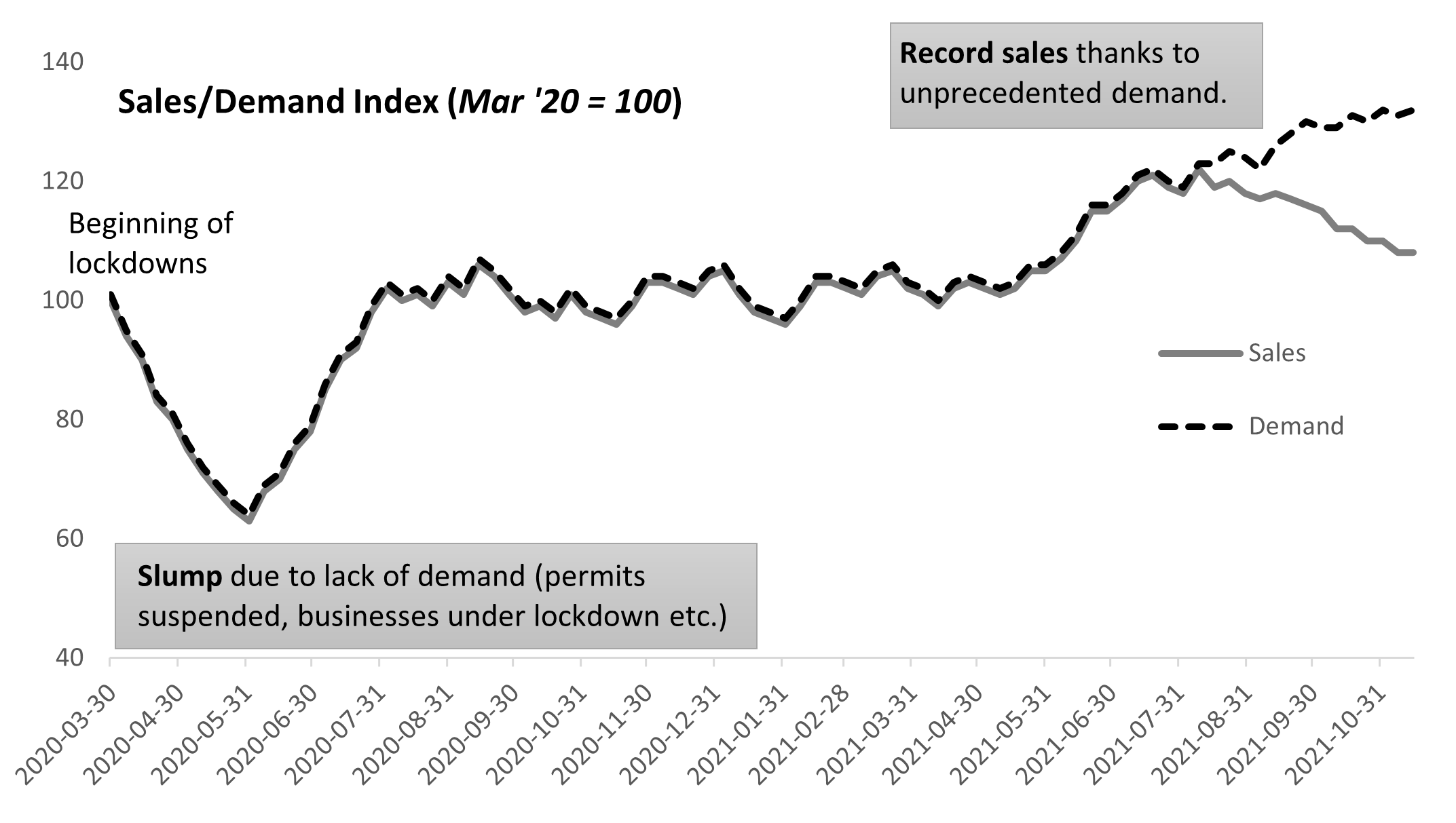

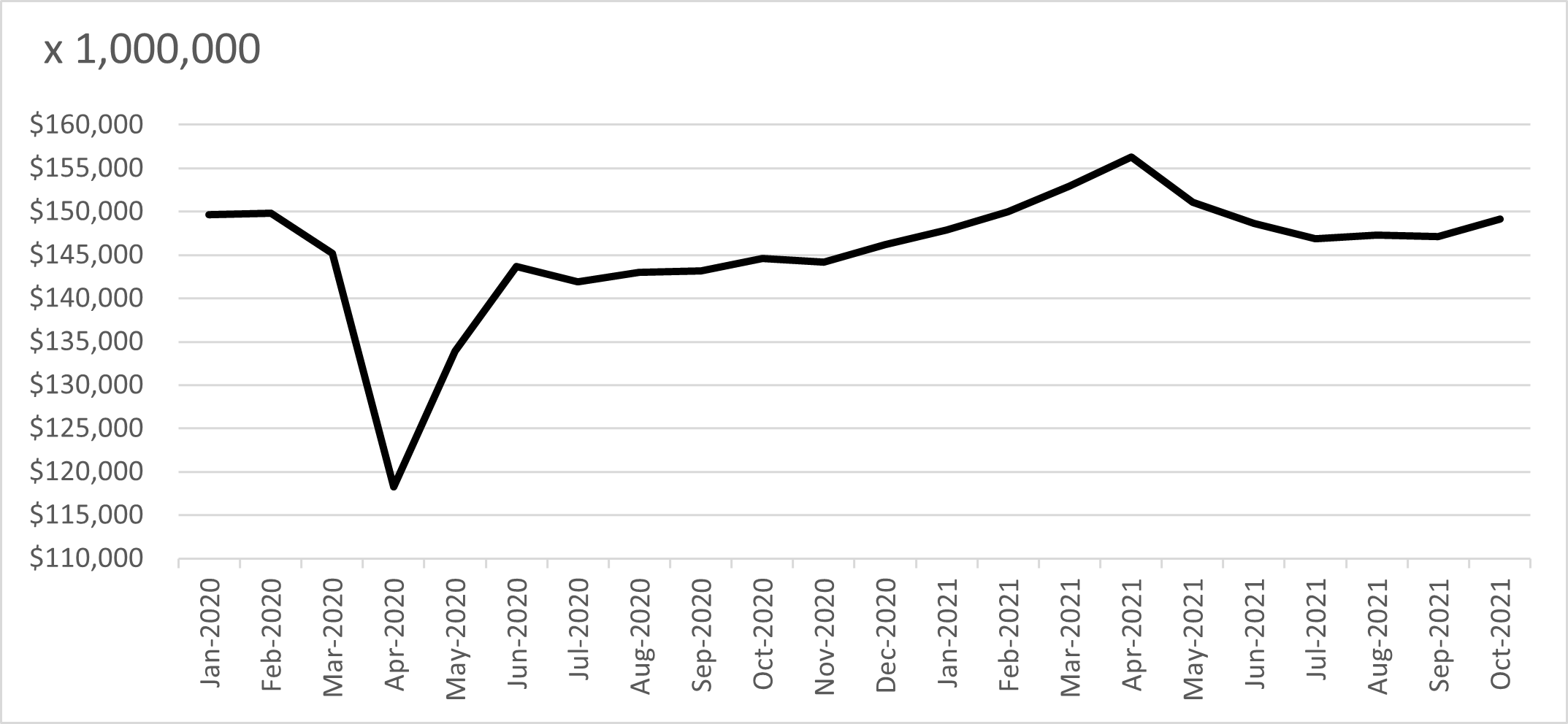

PWI’s sales and demand were tracked over the 86 weeks since the beginning of COVID-19 lockdowns , with the last five weeks forecasted. See Exhibit 3 − Approximation of PWI Sales & Demand Trajectory Since Lockdowns. In the initial months, government-imposed measures to minimize the pandemic’s cost to public health included the suspension of construction permits. Many businesses and residential occupants had to halt their renovation projects indefinitely. As a result, the demand from contractors for PWI products plummeted to historic lows. GDP numbers from the construction industry in Canada imply a similar demand trajectory. See Exhibit 4 − Construction Industry Monthly GDP in Canada Before and After the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic.

PWI had to respond to this extraordinary drop in sales by making the tough decision to scale down its operations, reduce order quantities from suppliers, and downsize its workforce. Gilbert explained that scaling down was not an easy decision for PWI management. Still, the uncertainty about the future was too high, and the company had to take steps to stay in survival mode while waiting for the markets to normalize. About eight weeks after the start of the lockdowns, the government eased up the restrictions, allowing contractors to restart their projects, provided they complied with the new public health protocols.[21] Thus, the demand that had sunk to its lowest point in nine weeks caught up with pre-pandemic levels in approximately the same amount of time. In Gilbert’s own words:

March of last year, when the Pandemic kind of loomed, all of us went into panic mode or control mode; none of us knew what [the] business was going to do. We all thought it would be extremely quiet; it was a great period of unknown at that point. I think all of us were pleasantly surprised at how fast it did bounce back by late May, even into June, we were seeing things start to pick up.

Although demand rose back to normal levels, PWI had to navigate another unexpected problem. With its reduced workforce, the company was having difficulties fulfilling customer orders due to reduced capacity in material handling operations, and the pandemic-stricken labour market was not offering any relief. Gilbert explained: “…getting people back or bringing new hires into the systems are always a problem.” It had grown even more complicated with people on emergency financial assistance from the government and prioritizing their health and well-being over going back to in-person workplaces.[22] Labour shortage had, therefore, become a chronic issue for PWI and the entire industry, both for office-based work and especially for warehouse positions.[23] PWI had to readjust its pay scales upward to attract more employees to address the issue. PWI also had to consider improving its processes and introducing automation in its warehouses and sale processes to reduce the number of workers required. Gilbert described the process,

In the last year (2020), we’ve added some robotics. (…) because you are in a warehouse [with big] walking distances, so they have point-to-point robots, where you drop a tote, and the robot transports [it] to wherever [needed]. We are now starting to look at, okay, when do we start automating the warehouse? When do we start [adding] automated pick towers? (…) It is a math exercise like anything is investment versus return.

The Situation in Fall 2021

After the early disruption, PWI’s sales slowly and steadily increased and reached historic highs at the end of the summer of 2021 (a 20% increase compared to pre-pandemic levels). Although PWI benefitted from this growth trend, the organization found itself in another unfamiliar territory during this time. Another unexpected impact of the pandemic on PWI was the drastic increase in suppliers’ prices. Suppliers were raising their prices as frequently as four times a year! In pre-pandemic times, prices rose once a year on par with the annual inflation rate. In the new post-pandemic environment, prices of some products saw a price hike of more than 50% cumulatively within just a year. Gilbert explained,

Our biggest vendor increased the prices such that a water heater that had been selling for $900 last fall was selling at $1400 one year later. Furthermore, intercontinental container shipment rates have jumped to record levels, up to tenfold in some cases compared to the previous year, adding to the supply cost pressure.

While managing the challenges due to severe cost inflation, PWI faced a more significant obstacle in the fall of 2021. Service levels from its suppliers started to drop considerably as none of its suppliers were able to ship the quantities ordered by PWI within the usual lead times. Shipments were either short in quantity or delayed in delivery by several weeks or months. PWI did not experience any limitations regarding warehousing space, but the suppliers were not able to ship sufficient products. The company found itself in uncharted territory. Gilbert indicated there were challenges in his role, as PWI was challenged to determine how to meet the demands of its customers. It became clear that PWI would not be able to ship the quantities customers requested on the sales orders and needed to develop a strategy to prioritize customers’ demands. PWI worked to determine the best criteria upon which to base their customer demand prioritization. Gilbert explained this concern,

Our biggest concern was trying to keep the product that our tier one customers needed. If they were not able to get the supplies from us, they would have to shift around their contractors from project to project depending upon the supplies they could find until they would have to halt their mega projects, all because they could not source basic products like piping or wiring. Our job transitioned from strategically planning our purchasing decisions to chasing product in the system in attempts to find at least some of what we were looking for to satisfy—and keep—our customers.

PWI handled a significant portion of its sales through email purchase orders that were automatically converted to sales orders in its ERP system (sales automation). Companies could also place their orders using PWI’s e-commerce website. The sales automation and e-commerce systems had been implemented within the last few years and provided PWI with significant cost savings in its operations. Thanks to the back-end integration of the inventory, sales, and e-commerce systems, customers could quickly check the inventory levels in each location and place their orders accordingly via email or through the website. Before the sales automation system, customers were required to go through sales agents to place their orders, which required manual communication between the buyers and sales agents. Freed from such tasks, sales agents now had more time to work on expanding the customer base.

PWI and its customers were satisfied with the efficiency of this ordering system, until the supply shortage unexpectedly hit PWI and its competitors. PWI could no longer allow the customers to order specific high-sales-volume products in the quantity they required because there were insufficient quantities in the inventory to satisfy all orders. PWI also noticed that some customers wanted to purchase in higher quantities only to stockpile as a way of safeguarding against scarcity and inflation.

Contractors had their construction projects planned and were, therefore, aware of the dates when they would require the plumbing, HVAC, PVF, and hydronics products. However, there was typically a shortage of appropriate holding space on construction sites, so receiving products early was discouraged. Thus, as a common practice, many PWI customers chose to reserve products to be shipped later. PWI had sufficient inventory space to accommodate this approach; therefore, it made sense from a customer satisfaction perspective to hold the shipments for several weeks. However, the viability of this policy, too, had to be reassessed due to the supply shortage and inflationary pressures.

Gilbert and his team now faced several imminent challenges. Frequent price hikes coupled with unreliable and extraordinarily long lead times from suppliers caused immediate product shortages, which demanded urgent management interventions.

Gilbert had to determine recommendations for the top management within weeks, if not days, regarding how to handle the e-commerce website and the sales automation system. PWI had invested a considerable amount of money, time, and resources in establishing the sales automation system and had benefitted from its operational and financial efficiencies for years. Customer feedback regarding the system was positive. However, Gilbert knew that it was not feasible for PWI to maintain the e-commerce website and the sales automation system operating as usual under the current, rapidly changing pandemic conditions. Something needed to be done, or PWI would have no inventory to provide to their top-tier customers.

Managing inventory also required a strategy for dealing with the increasing price hikes from suppliers. Gilbert had to decide when to reflect the price hikes from the suppliers to the customers. Whenever there were changes in prices, the suppliers communicated the new list to PWI. Category managers then had to determine whether to immediately reflect the increases in the purchasing costs to its existing inventory or wait until receiving the next batch with the inflated price.

PWI also had to determine how to revise its policy to allow customers to reserve products with delayed shipments.

Gilbert had to decide on some fast and efficient short-term solutions to recommend to PWI management to ensure his department could meet demands at a time filled with disruptions. Gilbert also had to recommend a long-term strategy to the management for how the company would respond to the frequent price hikes and manage its sales channels and inventory at a time of limited supplies in a way that avoided damaging the company’s relationship with the top-tier customers it relied upon for regular sales. Where should he start?

Exhibits

Exhibit 1 – Position of Pipework Warehouse Within the Construction Industry Supply Network

Source: Based on Xue, X., Li, X., Shen, Q., & Wang, Y. (2005). An agent-based framework for supply chain coordination in construction. Automation in Construction, 14(3), 413-430.

Credit: © Fatih Yegul, Jane Gravill & Juliet Conlon. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

[back]

Exhibit 2 – PWI Organization Chart

Source: Based on data supplied by Pipework Warehouse Inc.

Credit: © Fatih Yegul, Jane Gravill & Juliet Conlon. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

[back]

Exhibit 3 − Approximation PWI Sales & Demand Trajectory Since Lockdowns* (Indexed; March 2020 = 100)

*Note: Numbers indicated in the last five weeks were forecasted.

Source: Based on data supplied by Pipework Warehouse Inc.

Credit: © Fatih Yegul, Jane Gravill & Juliet Conlon. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

[back]

Exhibit 4 – Construction Industry Monthly GDP in Canada Before and After the Onset of the Covid-19 Pandemic

Source: Based on data from Statistics Canada. (2024). Table 36-10-0434-01 Gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, by industry, monthly (x 1,000,000). https://doi.org/10.25318/3610043401-eng

Credit: © Fatih Yegul, Jane Gravill & Juliet Conlon. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

[back]

Image Descriptions

Exhibit 1 – Position of Pipework Warehouse Within the Construction Industry Supply Network

The image is an organizational chart diagram illustrating different roles and entities in the supply chain network. A box at centre is labelled “general contractor.” At the top centre is a box labelled “property owner,” flowing up from property owner are three suppliers. At left is a box labelled “designer,” flowing further left are structural, architectural, electrical, and other designers grouped together. Below are three additional suppliers. To the right are civil contractor, equipment contractor, and other contractors, linked together, flowing further right are suppliers A, B, and Pipework Warehouse. Flowing down from Pipework Warehouse are distributors, manufacturers, and raw materials suppliers.

[back]

Exhibit 2 – PWI Organization Chart

The image is a hierarchical organizational chart featuring a tree structure with several levels. At the top is “CEO / President.” Below this, there are five main branches: “Director, Finance,” “Sales Growth Manager, Plumbing,“ “Sales Growth Manager, HVAC,” “Manager, HR,” and “VP, Supply Chain.” Each of these roles further branches out:

- “Director, Finance” connects to “Manager, AR” leading to “AR Staff” and “Controller” leading to “Finance Staff.”

- “Manager, IT” connects to “IT Staff.”

- Both “Sales Growth Manager, Plumbing“ and “Sales Growth Manager, HVAC” have a branch to “Product Managers.” There is an arrow pointing to “Product Managers” with a label “Troy Gilbert.”

- “Manager, HR” connects to “HR Staff.”

- “VP, Supply Chain” connects to “Purchasing Staff” and “Warehouse Staff.”

[back]

Exhibit 3 − Approximation PWI Sales & Demand Trajectory Since Lockdowns* (Indexed; March 2020 = 100)

The image depicts a line graph with the date range on the x-axis and the index values from 40 to 140 on the y-axis. Two lines are plotted: a solid gray line represents sales and a black dashed line represents demand. Both lines start around index 100 in March 2020. Both lines initially dip sharply, reaching their lowest point below 60 by mid-2020, before gradually rising with fluctuations. In mid-2021, the sales line goes down towards index 100 while the demand line goes up towards 130. Key annotations include “Beginning of lockdowns” at the chart start, “Slump due to lack of demand (permits suspended, businesses under lockdown etc.)” in mid-2020, and “Record sales thanks to unprecedented demand” in 2021 when the lines split.

[back]

Exhibit 4 – Construction Industry Monthly GDP in Canada Before and After the Onset of the Covid-19 Pandemic

The image depicts a line graph where the x-axis represents time, ranging from January 2020 to October 2021, with each month marked. The y-axis represents a monetary value in millions of dollars, starting from $110,000 to $160,000, with increments of 5,000. The line begins at the $150,000 mark in January 2020 and decreases sharply until April 2020, reaching an approximate low of $118,000. The line quickly rises to almost $145,000 in June 2020, then gradually increases, peaking above 150,000 in April 2021. The line slightly declines and stabilizes around $150,000 by October 2021.

[back]

References

Antunes, P. (2020, July 9). Extend wage subsidy program, not individual response benefits. The Globe and Mail.

BIMCO. (2021, January 13). Ships make the world go [Video].

Boudreau, J., Nguyen, D., & Chau, M. (2021, November 8). Factory’s open. Where’s the staff? Bloomberg Businessweek, 40-41.

Britain’s economic recovery from the pandemic is far from smooth. (2021, September 2). The Economist.

Cassidy, W.B. (2022, January 3). A supply chain still upside down: Shippers seek resilience in upended transportation markets. Journal of Commerce, 23(1), 8−14.

Conerly, B. (2021, July 7). The labor shortage is why supply chains are disrupted. Forbes.

Contreras, Z., Ngo, V., Pulido, M., Washburn, F., Gluck. F., Meschyan, G., Kuguru, K., Reporter, R., Curley, C., Civen, R., Terashita, D., Balter, S., & Halai, U. (2021). Industry sectors highly affected by worksite outbreaks of coronavirus disease, Los Angeles County, California, USA, March 19–September 30, 2020. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 27(7), 1769−1775.

Dubay, C. (2021, September 8). Worker shortage crisis intensifying as job openings rise month over month. U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Eschner, K. (2021, December 2). Backlog at the Port of Vancouver is a sign of supply-chain disruption to come. Fortune.

Fox, C. & Herhalt, C. (2020, May 14). Phase 1 of Ontario’s reopening to allow all construction, most retail, individual sports. CP24.

Kinsey, A. (2021, November). Shipping risks strain global supply chains. Risk Management, 19.

Labs, W. (2020, June). Food Engineering’s 43rd annual plant construction survey. Food Engineering, 31−36.

Page, C. (2020, October 10). PC sales just broke a 10-year record thanks to the pandemic. Forbes.

Simionato, C. (2022, January 13). Sales of electrical, plumbing, heating and air-conditioning equipment and supplies merchant wholesalers in Canada from 2012 to 2020. Statista.

Statista. (2020, April). Sales growth of personal care and cleaning products due to the coronavirus outbreak in Canada in March 2020.

Statistics Canada. (2023). Table 20-10-0008-02 Retail trade sales by industry (x 1,000).

Statistics Canada. (2024). Table 36-10-0434-01 Gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, by industry, monthly (x 1,000,000).

Szakonyi, M. (2021, August 21). Montreal port strike truce reached, but cargo backlog to last weeks. Journal of Commerce Online.

Taylor, H. (2021, April 3). Suez Canal blockage: Last of the stranded ships pass through waterway. The Guardian.

UNCTAD (2021, April). Container shipping in times of COVID-19: Why freight rates have surged and implications for policymakers [PDF]. United Nations.

Xue, X., Li, X., Shen, Q., & Wang, Y. (2005). An agent-based framework for supply chain coordination in construction. Automation in construction, 14(3), 413−430.

Download a PDF copy of this case [PDF].

Read the Instructor’s Manual Abstract for this case.

How to cite this case: Yegul, F., Gravill, J. & Conlon, J. (2024). Pipework Warehouse Inc.: Managing disruptions in supply and demand. Open Access Teaching Case Journal, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.58067/phzg-3464

The Open Access Teaching Case Journal is a peer-reviewed, free to use, free to publish, open educational resource (OER) published with the support of the Conestoga College School of Business and the Case Research Development Program and is aligned with the school’s UN PRME objectives. Visit the OATCJ website [new tab] to learn more about how to submit a case or become a reviewer.

ISSN 2818-2030

- Simionato, 2022. ↵

- stock keeping units ↵

- A search in Gale OneFile News Database with the term “supply chain” in document titles one year before and after March 11, 2020, (when the WHO declared COVID-19 as pandemic) reveals a 64% increase in the number of reports published in news outlets globally. ↵

- Cassidy, W.B. (2022, January 3). A Supply chain still upside down: Shippers seek resilience in upended transportation markets. The Journal of Commerce, 23(1) 8-14. ↵

- BIMCO, 2021. ↵

- Statista, 2020. ↵

- Page, 2020. ↵

- Statistics Canada, 2023. ↵

- Britain’s economic recovery from the pandemic is far from smooth, 2021. ↵

- UNCTAD, 2021. ↵

- UNCTAD, 2021. ↵

- Taylor, 2021. ↵

- Kinsey, 2021. ↵

- Szakonyi, 2021. ↵

- Eschner, 2021. ↵

- Labs, 2020. ↵

- Contreras et al., 2021. ↵

- Boudreau, J., Nguyen, D., & Chau, 2021. ↵

- Dubay, 2021. ↵

- Britain’s economic recovery from the pandemic is far from smooth, 2021. ↵

- Fox & Herhalt, 2020. ↵

- Antunes, 2020. ↵

- Conerly, 2021. ↵