11 Week 11 Communicating Financial Information

Week 11 – Communicating Financial Information

Introduction

Learning Objectives

Learning Objectives

By the end of this week you will be able to:

- Understand what makes a good public speaker

- Understand and construct a compelling presentation

This chapter should take you 15 minutes to read.

Being a good public speaker doesn’t come naturally to everyone. In fact, it doesn’t come naturally to most people. Being a good public speaker requires confidence, clarity and excellent communication. However, if you are interested in working within Creative Industries, at some point you will be required to give compelling presentations – either to sell an idea, or yourself or both.

With that in mind, it is important that you have some basic public speaking skills. Public speaking is something that gets better with time. The more presentations you do, the better you get. But your growth depends on the tips and tricks you learn along the way.

Activity: Powerpoint, Powerpoint, Powerpoint – The Office US [4:05]

Activity: Powerpoint, Powerpoint, Powerpoint – The Office US [4:05]

How to Give a Great Presentation

The best presentations aren’t often by the most charismatic people but often the ones who put the effort, energy and enthusiasm into preparing. You can’t control your nerves but you can control your approach and how well you prepare for your presentation. Here are the most important things to keep in mind while presenting.

Frame Your Story

There’s no way you can give a good talk unless you have something worth talking about. Conceptualizing and framing what you want to say is the most vital part of preparation.

We all know that humans are wired to listen to stories, and metaphors abound for the narrative structures that work best to engage people. When I think about compelling presentations, I think about taking an audience on a journey. A successful talk is a little miracle—people see the world differently afterward.

If you frame the talk as a journey, the biggest decisions are figuring out where to start and where to end. To find the right place to start, consider what people in the audience already know about your subject—and how much they care about it. If you assume they have more knowledge or interest than they do, or if you start using jargon or get too technical, you’ll lose them. The most engaging speakers do a superb job of very quickly introducing the topic, explaining why they care so deeply about it, and convincing the audience members that they should, too.

Many of the best talks have a narrative structure that loosely follows a detective story. The speaker starts out by presenting a problem and then describes the search for a solution. There’s an “aha” moment, and the audience’s perspective shifts in a meaningful way.

Plan Your Delivery

Once you’ve got the framing down, it’s time to focus on your delivery. There are three main ways to deliver a talk. You can read it directly off a script or a teleprompter. You can develop a set of bullet points that map out what you’re going to say in each section rather than scripting the whole thing word for word. Or you can memorize your talk, which entails rehearsing it to the point where you internalize every word—verbatim.

My advice: Don’t read it, and don’t use a teleprompter. It’s usually just too distancing—people will know you’re reading. And as soon as they sense it, the way they receive your talk will shift. Suddenly your intimate connection evaporates, and everything feels a lot more formal.

Many of the best and most popular TED Talks have been memorized word for word. If you’re giving an important talk and you have the time to do this, it’s the best way to go. But don’t underestimate the work involved. Obviously, not every presentation is worth that kind of investment of time. But if you do decide to memorize your talk, be aware that there’s a predictable arc to the learning curve. Most people go through what I call the “valley of awkwardness,” where they haven’t quite memorized the talk. If they give the talk while stuck in that valley, the audience will sense it. Their words will sound recited, or there will be painful moments where they stare into the middle distance, or cast their eyes upward, as they struggle to remember their lines. This creates distance between the speaker and the audience.

Getting past this point is simple, fortunately. It’s just a matter of rehearsing enough times that the flow of words becomes second nature. Then you can focus on delivering the talk with meaning and authenticity. Don’t worry—you’ll get there.

Stage Presence and Nerves

For inexperienced speakers, the physical act of being onstage can be the most difficult part of giving a presentation—but people tend to overestimate its importance. Getting the words, story, and substance right is a much bigger determinant of success or failure than how you stand or whether you’re visibly nervous. And when it comes to stage presence, a little coaching can go a long way.

The biggest mistake in early rehearsals is that people move their bodies too much. They sway from side to side, or shift their weight from one leg to the other. People do this naturally when they’re nervous, but it’s distracting and makes the speaker seem weak. Simply getting a person to keep his or her lower body motionless can dramatically improve stage presence. There are some people who are able to walk around a stage during a presentation, and that’s fine if it comes naturally. But the vast majority are better off standing still and relying on hand gestures for emphasis.

Perhaps the most important physical act onstage is making eye contact. Find five or six friendly-looking people in different parts of the audience and look them in the eye as you speak. Think of them as friends you haven’t seen in a year, whom you’re bringing up to date on your work. That eye contact is incredibly powerful, and it will do more than anything else to help your talk land. Even if you don’t have time to prepare fully and have to read from a script, looking up and making eye contact will make a huge difference.

Another big hurdle for inexperienced speakers is nervousness—both in advance of the talk and while they’re onstage. People deal with this in different ways. Many speakers stay out in the audience until the moment they go on; this can work well, because keeping your mind engaged in the earlier speakers can distract you and limit nervousness. Amy Cuddy, a Harvard Business School professor who studies how certain body poses can affect power, utilized one of the more unusual preparation techniques I’ve seen. She recommends that people spend time before a talk striding around, standing tall, and extending their bodies; these poses make you feel more powerful. It’s what she did before going onstage, and she delivered a phenomenal talk. But I think the single best advice is simply to breathe deeply before you go onstage. It works.

In general, people worry too much about nervousness. Nerves are not a disaster. The audience expects you to be nervous. It’s a natural body response that can actually improve your performance: It gives you energy to perform and keeps your mind sharp. Just keep breathing, and you’ll be fine.

Acknowledging nervousness can also create engagement. Showing your vulnerability, whether through nerves or tone of voice, is one of the most powerful ways to win over an audience, provided it is authentic. Susan Cain, who wrote a book about introverts and spoke at the HBR 2012 conference, was terrified about giving her talk. You could feel her fragility onstage, and it created this dynamic where the audience was rooting for her—everybody wanted to hug her afterward. The fact that we knew she was fighting to keep herself up there made it beautiful, and it was the most popular talk that year.

Plan the Multimedia

With so much technology at our disposal, it may feel almost mandatory to use, at a minimum, presentation slides. By now most people have heard the advice about PowerPoint: Keep it simple; don’t use a slide deck as a substitute for notes (by, say, listing the bullet points you’ll discuss—those are best put on note cards); and don’t repeat out loud words that are on the slide. Not only is reciting slides a variation of the teleprompter problem—“Oh, no, she’s reading to us, too!”—but information is interesting only once, and hearing and seeing the same words feels repetitive. That advice may seem universal by now, but go into any company and you’ll see presenters violating it every day.

Many of the best speakers don’t use slides at all, and many talks don’t require them. If you have photographs or illustrations that make the topic come alive, then yes, show them. If not, consider doing without, at least for some parts of the presentation. And if you’re going to use slides, it’s worth exploring alternatives to PowerPoint like Prezi.

You can use an array of platforms to create a great presentation. Images, graphs, and video clips liven things up, especially if the information is dry. Here are a few pointers:

- Don’t put blocks of text on a single slide

- Use a minimalistic background instead of a busy one

- Don’t read everything off the slide

- Maintain a consistent font style and size

- Place only your main points on the screen. Then, explain them in detail. Keep the presentation stimulating and appealing without overwhelming your audience with bright colors or too much font

- Follow the 10-20-30 rule – Guy Kawasaki, a prominent venture capitalist and one of the original marketing specialists for Apple, said that the best slideshow presentations are less than 10 slides, last no longer than 20 minutes, and use a font size of 30. This strategy helps condense your information and maintain the audience’s focus.

First Impressions Count

What they say about first impressions are true – they’re often what leave a lasting impression. Try to start your presentation with something that will catch your audience’s attention, like:

- A question

- A short video

- An artifact you can pass around

- A joke or other antidote

- A memorable first image – a picture of what you’re trying to sell them or something else completely that catches them off guard.

Organizing your financial information

On top of improving your presentation skills it is also important that your information is clear and easy to understand. If you are ever pitching a company or idea there are key rules you need to follow in regards to the way you present your finances.

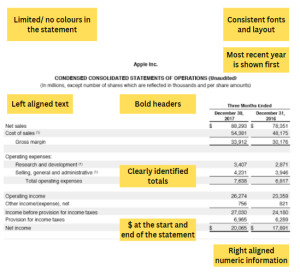

The formatting of your financial documents should stay consistent and clear. You can bring a few colours into your financial documents, ideally adding only one colour and making the information monochromatic. Keep in mind that different colours are good at doing different things, if there is a lot of text making it black/dark makes it easier to read, while bold colours attract attention to the key features you are hoping to highlight. Be mindful of what different colours represent in different cultures and how your audience will perceive them.

Just like having limited colours you should keep your fonts consistent and limited. To make things standout you can use the bold, italics and underlining features instead. Think about where this font is going and how it will look on different medians, your primary goal is to make the information easy to follow and understand.

On top of stylist rules keep in mind formatting rules for the data you have. Numbers should be right aligned while text is left aligned, this makes it easier to compare the data. Make sure that all of your rounding is consistent and does not provide unnecessary information. Include all the necessary information the reader would need to know like what data are they looking at, for which company, during which time period, etc. Be as concise as possible while making sure the audience knows exactly what you are referencing.

The main goal with presenting financial information is to make it easy to follow and see the key details letting people make key decisions and evaluations of the company.

Final Thoughts

All of the greatest public speakers of our time started somewhere. Practice truly does make perfect when it comes to public speaking. So go off and speak!

Sources

https://hbr.org/2013/06/how-to-give-a-killer-presentation

https://www.betterup.com/blog/how-to-give-a-good-presentation

https://accountingware.com/activreporter/blog/formatting-best-practices-for-financial-statements