First Principles in Research Data Management

3 Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Moving Toward Self-Determination and a Future of Good Data

Moving Toward Self-Determination and a Future of Good Data

Mikayla Redden and Dani Kwan-Lafond

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

- Articulate the importance of Indigenous data sovereignty and its role in Indigenous self-determination.

- Identify deficit-focused data and explain why these type of data are harmful.

- Identify the differences in assumptions made by Western/dominant research culture and Indigenous research culture and understand how these assumptions affect data-related decision making in the research process.

Introduction

Indigenous Peoples is perhaps one of the broadest umbrella terms frequently applied to a contemporary global population of colonized and formerly colonized peoples who, today, are politically united because of a shared history of loss and degradation under colonization. This chapter focuses on the history and present-day iterations of knowledge theft and knowledge mining (defined in this context as collecting Indigenous knowledge without seeking permission or consulting partners in the community) from Indigenous communities, as well as the Indigenous communities’ sovereignty of their own data. Knowledge mining and data sovereignty intersect because digital data is the most common way to store and archive knowledge for use by community members and researchers.

To begin, we will present a brief history of the global political community of Indigenous Peoples, with a focus on the impact of the United Nations Declaration on the Right of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in Canada. In the Canadian context and for the purposes of this chapter, Indigenous is used to broadly refer to three ethnically and culturally distinct groups: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit.

The United Nations and Indigenous Self-Determination

UNDRIP was adopted in 2007 by all United Nations (UN) member states except for four settler colonial nation states: Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and the United States. These four later signed the Declaration in 2012 after considerable efforts by Indigenous Peoples in these members states and their allies. UNDRIP is an extension of the human rights system, which is most clearly articulated in the 1960 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. UNDRIP contains no new human rights, but is an articulation and affirmation of rights often denied to Indigenous Peoples (Erueti, 2022).

The access to, or denial of, rights to Indigenous Peoples is globally disparate. While settler states are partially defined by their majority rule over Indigenous communities within their borders, there are always local, historical, and culturally specific aspects to these contexts that we must consider. Local contexts will impact how access and control of data, information, and knowledge are negotiated and decided on, but are too numerous to delve into here. Instead, we point to the need to also understand policy, and the role policy frameworks can play in promoting and assuring data sovereignty, while preventing knowledge theft and knowledge mining.

UNDRIP is the most well-known and recent human rights framework that seeks to redress and uphold rights for Indigenous Peoples. But it is important to mention the International Labour Convention (ILO) 169 (1989), which most nation states in Central and South America had already signed/adopted before UNDRIP was developed. The ILO is a UN-affiliated agency with a focus on workers and working conditions in member nation states. ILO 169 itself was a revision and renaming of the Indigenous and Tribal Populations Convention 107 (1957), which arose in the wake of World War II out of a concern about discrimination and oppression faced by Indigenous Peoples.

ILO 107 and the revised ILO 169 are laws in the nation states that adopt them (Hanson, n.d-a; n.d-b). ILO 169 consists of 44 articles that set minimum standards in the areas of health care, education, and employment. It also recognizes rights to self-determination and calls upon nations states to protect Indigenous Peoples from displacement (Hanson, n.d-a; n.d-b). Whereas previous human rights frameworks used individual rights as the basic unit, UNDRIP extends these rights to collective groups of Indigenous Peoples, including those living as minority groups within larger nation states (as is the case in Canada). This important global framework emphasizes not only collective rights and identities, but also self-determination and the right to free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC). It also refers to historical wrongs and offers ideas for reparative measures (Erueti, 2022). The passage of UNDRIP was aspirational, insofar as it depends on each member nation to pass legislation that makes UNDRIP law (unlike ILO 169).

A History of Indigenous Peoples and Bad Data

Engagement between Indigenous Peoples and the governments in their Anglo-colonized countries centres on administrative policies and the programming that stems from them. This is certainly true in a Canadian context, where the mandate for Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) reads, in part, “Our vision is to support and empower Indigenous peoples to independently deliver services and address the socio-economic conditions in their communities” (Indigenous Services Canada, 2022). ISC focuses on disadvantages and social disparities of Indigenous Peoples and how the colonial nation state can help them. The same can be said when looking at mandates by the United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs (2023) and at the National Indigenous Australians Agency’s Closing the Gap framework (2019) (for a detailed analysis of these policies, see Walter et al. in the Additional Resources section). Each of these colonial organizations situate data as the basis for their policy decisions.

Across all these countries, data paint a picture of Indigenous Peoples as having poorer health, lower education levels, and lower socio-economic status, which results in, and often numerically justifies, their startling high rates of incarceration, victimization, and suicide. All of these nations had active policies to assimilate Indigenous Peoples into Anglo-colonial society by forcibly removing children from their families and communities. These data are not disputed by Indigenous folks, but the social, racial, and cultural assumptions made by those collecting the data are questioned (Walter & Andersen, 2013). These assumptions provide us with only a narrow, colonized snapshot of Indigenous realities (Walter & Suina, 2019). As a result, the policies and programs developed using these data do not reflect the needs of Indigenous Peoples. All data collected from Indigenous Peoples should be their own to control, access, interpret, and manage.

This chapter will introduce this idea, known as Indigenous data sovereignty, which is defined as the right of Indigenous Peoples to collect, access, analyze, interpret, manage, distribute, and reuse all data that was derived from or relates to their communities. This chapter will also discuss the frameworks and strategies that affirm Indigenous data sovereignty in the dominant research culture.

Indigenous Data: What is it? How Would It Be Different Under Indigenous Self-Determination?

Indigenous data is a broad term referring to information and knowledge about individuals, groups, organizations, ways of knowing and living, languages, cultures, land, and natural resources. It exists in many formats, including traditional knowledge, which is defined as information that is passed down between generations. Traditional knowledge includes languages, stories, ceremonies, dance, song, arts, hunting, trapping, gathering, food and medicine preparation and storage, spirituality, beliefs, and world views. Indigenous data also include born-digital and digitized data collected by researchers, governments, and non-governmental institutions (Walter 2018; Kukutai & Taylor, 2016; Walter et al., 2021; Walter & Suina, 2019).

Across colonized nations, Indigenous data collected by governmental and non-governmental researchers are focused on differences, disparities, disadvantages, dysfunction, and deprivation of Indigenous Peoples — abbreviated as 5D data by Walter (2016; 2018). 5D data are lacking in social and cultural context due to their collection and analysis by researchers and policymakers coming from non-Indigenous world views and comparing the data against their colonial realities. No matter the analyses conducted, the policy-forming statistics are invalid because they are produced from 5D data and, therefore, focus entirely on deficits (Walter & Suina, 2019).

Data needs vary widely among Indigenous communities, but there is a consensus that all Indigenous data should reflect the social, political, cultural, and historical realities of Indigenous lives so that it can be used to support the self-determined needs of Indigenous Peoples (Walter, 2018; Walter & Suina, 2019). These data needs are central to the global Indigenous data sovereignty movement and are affirmed by the UNDRIP.

The Indigenous data sovereignty movement advocates for self-governance, meaning that Indigenous Peoples would control all aspects of the research process, from idea conception to use of resulting data. Without Indigenous data sovereignty, there is no way to ensure that Indigenous data reflects the rich diversity in Indigenous world views, ways of knowing, priorities, cultures, and values (Walter & Suina, 2019).

Indigenous Data Self-Governance Organizations in Anglo-Colonized Nations

- Canada: First Nations Information Governance Centre

- Australia: Maiam nayri Wingara

- New Zealand: Te Mana Raraunga

- United States Data Sovereignty Network

Interacting with Indigenous Knowledge

Before getting into best practices for working with Indigenous data, you should be aware of the following assumptions that differ between Indigenous and Eurocentric research practices.

| Eurocentric assumption | Indigenous assumption |

| Researchers remain objective and unbiased. | Research is NOT objective and unbiased. It can’t be. Researchers are connected to all living things — this includes the human or non-human subjects of their research. Emotions are connected to cognition. When we think, we use reason, which is tied to our emotions, making research subjective. |

| Research is planned and led by the researcher(s). |

Research is community based. Community members always shape the research question. No matter the topic, research allow us to gather knowledge that works toward one common goal: to create social action. Knowledge paired with action leads to social change.

|

| The researcher is largely unaffected by the research process. | Personal growth of the researcher is an important result (because research is subjective). |

| No piece or member of the sample is more valuable than the others (outside of a case study). | The eldest community members most likely carry the most valuable knowledge. If elders are not involved in the research process, it is not based in traditional knowledge. One caveat to keep in mind here is that not all elder community members are “Elders.” There are younger community members who carry traditional knowledge or language. Therefore, the terms “Traditional Teacher,” “Knowledge Keeper,” or “Language Keeper” are more descriptive than simply referring to all traditional peoples as “Elders.” |

In addition to these four assumptions, Indigenous Peoples consider the following four Rs during the entire research cycle, including publication: Relationality, Respect, Reciprocity, and Responsibility.

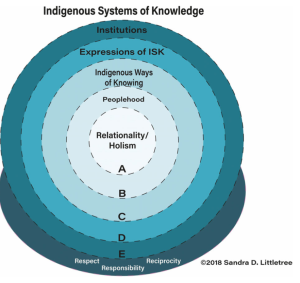

- Relationality is the centre of everything in Indigenous world views and knowledge systems (Wilson, 2008). Relationships inform all of our experiences; as Littletree, Belarde-Lewis, and Duarte (2020) put it, they are “at the heart of what it means to be Indigenous.” As we engage with the world, it is our relationships that ensure we are accountable to our relations in every one of our interactions. Our relations include the land, our ancestors, and future generations. We are our relationships and are, in fact, made up of relationships between four realms: the intellectual, spiritual, emotional, and physical parts of ourselves (Archibald, 2008). It is essential that researchers interested in Indigenous ways of knowing understand that all data, books, articles, stories, art, and other outputs began as relationships (Meyer, 2008). These things are a result of Peoplehood, defined as communal knowing. An example of this is shared histories and languages, ceremonies, celebrations, and life cycles (Holm, Pearson, & Chavis, 2003). Indigenous ways of knowing are where those relationships turn into actions. Some examples of this are asking questions, watching dance, listening to relations, dreaming, telling stories, experiencing life events, making art, and intergenerational activities like planting seeds and nurturing them as they grow into something we harvest in the fall. The Expressions of these ways of knowing are tangible items like documents, songs, tools, traditional dress, written and oral stories, books, food, paintings, carvings, and pottery. These Expressions are often held by knowledge organizations, such as libraries, museums, schools, sacred organizations, and Indigenous nations (Kidwell, 1993). The relationality at the centre of these items is often missed by non-Indigenous researchers and knowledge organizations. For a deeper understanding of relationality, see Littletree’s (2018) conceptual model. Also see Holm, Pearson, and Chavis (2003); Archibald (2008); Wilson (2008); Meyer (2008); and Kidwell (1993), whose work informed the model.

Respect, reciprocity, and responsibility support relationality.

- Respect for land, cultural protocols, history, language, and intellectual, spiritual, emotional, and physical health. Do not make assumptions about the knowledge you are working with. Use an educated, but open-minded approach. The knowledge you are inquiring about may be associated with painful historical events and elicit a great deal of trauma.

- Reciprocity for the information you are receiving. Be open to give and receive information. There is a long history of knowledge mining from Indigenous communities by settlers. Reciprocity does not solely refer to monetary compensation, although it is important to financially compensate individuals and communities for their time and information. Reciprocity also includes supporting communities in recovering traditions and important cultural expressions.

- Responsibility to obtain informed consent and nurture any relationships you have built for life — well past the end of the research project. Indigenous world views tell us that time is non-linear; it is circular. The community you are working with must guide the process and make decisions about their knowledge and information at every step.

For an in-depth look at these assumptions and considerations, see Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods (2008) by Shawn Wilson and “Centering Relationality: A Conceptual Model to Advance Indigenous Knowledge Organization Practices” (2020) by Sandra Littletree, Miranda Belarde-Lewis, and Marisa Elena Duarte.

First Nations Data Self-Governance in Canada

In 1994, the federal government excluded First Nations people who live on-reserve from national population surveys (First Nations Information Governance Centre, 2022a; 2002b). In response to the data gap this created, First Nations advocates and academics formed what would later become the First Nations Information Governance Centre. Two years later, the Assembly of First Nations formed the National Steering Committee (NSC), which was tasked with developing the First Nations and Inuit Regional Longitudinal Health Survey, an early iteration of what is now known as the First Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS). The first Survey report was published in 1997 (First Nations Centre, 1997). The RHS is the only national health survey that is governed by Indigenous Peoples and based on both Indigenous and Western understandings of health and well-being. It was later reviewed by a group at Harvard University who determined that it was, “unique in First Nations ownership of the research process, its explicit incorporation of First Nations values into the research design and in the intensive collaborative engagement of First Nations people and their representatives at each stage of the research process” (Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development, 2006).

In 1998 the NSC established a set of principles called the First Nations Principles of OCAP® to ensure that First Nations people were stewards of their own information in the same way they are stewards of their own lands. The NSC later became the First Nations Information Governance Committee and, later, an incorporated nonprofit called the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC).

OCAP® is an acronym for ownership, control, access, and possession. These four principles govern how First Nations data and information should be collected, protected, used, and shared. OCAP® was created because Western laws do not recognize the community rights of Indigenous Peoples to control their information. The principles are reflective of Indigenous world views on stewardship and collective rights. Historically, Indigenous Peoples have not been consulted about information collected about them, nor who collects it, how they store it, or who else has access to it. As a result of this lack of self-governance, data collection has lacked relevance to the priorities and concerns of Indigenous Peoples.

The principles affirm the rights and self-determination of Indigenous communities to own, control, access, and possess information about their peoples and asks any researchers interested in conducting research with an Indigenous community to learn the principles before they begin. The principles can benefit anyone who works with (or hopes to work with) Indigenous research, data, information, or cultural knowledge and supports Indigenous Peoples’ path to data sovereignty (FNIGC, 2022). FNIGC and Algonquin College have developed an online course to train researchers in the principles and history of OCAP®.

The First Nations Principles of OCAP®

- Ownership: Communities or groups collectively own their own knowledge, data, and information in the same way that individuals own their own personal information.

- Control: Communities have control over all stages of research, from collection to storage and everything in between. Communities have control and decision-making power over all aspects of research and information that impacts them.

- Access: Communities should be able to access their collective information and data, no matter its location. Communities should be able to manage and make decisions regarding the access to and control of their information.

- Possession: This is like Ownership, but more concrete. It is the physical control of data, the mechanism that asserts and protects ownership of information. It may also be thought of as stewardship.

A Non-Exhaustive List of Strategies for Conducting Research That Respects OCAP®

(Adapted from Schnarch (2005), National Aboriginal Health Organization (2005), and First Nations Information Governance Centre (2016))

- Prepare for it to take more time. You will need to get permission from community decision-makers like the Chief and Council, advisory committees, and Knowledge Keepers in addition to your research ethics board, individual participants, funding agencies, etc. Community consent is as important as the informed consent of individual participants. Research must be suspended if the community does not consent.

- Negotiate the research relationship and create a written agreement that affirms your rights and responsibilities as well as those of the community and all other partners in the research process. Be sure that all parties understand, agree, and receive a copy of the document.

- Seek funding sources that have policies that affirm Indigenous self-determination and sovereignty.

- Provide explanations and seek feedback for all aspects of the project. This can include your purpose, the anticipated benefits and risks of the project, the methods you plan to use, how you recruit your participants, how you plan to report your findings, and what you plan to do with the resulting data.

- Respect the privacy, cultural and community protocols, well-being, and individual and collective rights of Indigenous Peoples. Follow stringent ethical guidelines. Develop a code of research ethics or guidelines specific to the project. Be sure to consider that each community may have distinct interpretations and comfort levels with OCAP® and other self-determination frameworks.

- Support the interests of the community and maximize the benefits of the work. This includes building on successful Indigenous initiatives and providing opportunities for further capacity building.

- Submit all communications, summaries, and reports of your research to the community in the appropriate language prior to publication.

- Ensure that Indigenous communities have access to their data, not just the reports and resulting publications.

Critical Analysis of OCAP®

Critics might say that a necessary precursor to Indigenous controlled data and research is capacity development. They may argue that there is a lack of expertise within the community, which could lead to risks and consequences. Some would encourage First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples with existing credentials in higher education to become involved, or even encourage folks from the community without existing credentials to obtain some that are related to research.

Both of these solutions could benefit individuals, but do they support nation and community building in addition to career building? Obtaining higher education credentials often requires leaving the community, which can alienate them from their communities. Not so long ago, choosing to go to university forced First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples to relinquish their Indian identities and status and assimilate into white settler society. The real beneficiaries in this situation are the institutions where individuals go to study under or work for.

Opportunities to work as a full-time researcher within communities are very rare. The ability to walk in two worlds (i.e., balance Indigenous values and manage community responsibilities while advancing academic careers) is challenging, often forcing folks to make a difficult choice between the two. Furthermore, suggesting that communities cannot conduct ethical and beneficial research on their own is harmful at best. Research does not have to be specialized, use complex methodologies, or be full of scientific jargon to be beneficial.

Looking to the Future with OCAP®

At this point in time, the Principles of OCAP® are the strongest tool First Nations people in Canada and their allies have in asserting their sovereignty over data. The principles have the capacity to challenge bad data and research practices and encourage good ones. Still, there are challenges we face in moving forward in a meaningful way.

- For Research Ethics Boards: Assess all research applications going forward for OCAP® principles, or another appropriate framework, so that all research is compliant. But what about assessment of ongoing and historical research against OCAP®? After all, substantial harm has been caused to Indigenous communities via exploitative research practices. Does Truth and Reconciliation not remain a stated commitment of many educational institutions and governmental bodies?

- For policy writers: Address the ownership, control, access, and possession of data and research for all policies, and review previous policies. Some examples of existing policies that affect community-based research are institutional fire and smoking policies; data storage and dissemination policies; and intellectual property policies.

- For researchers: Be flexible, willing to compromise, and able to challenge your own assumptions about the ownership, control, access, and possession of the work that you may see as “yours.” Remember that true community-based research aims to create positive and Indigenous-determined social action.

- For data management professionals: Consider the community a research project is focused on before you develop a Data Management Plan. Defer to the community to assess their understanding of and comfort level with data self-determination no matter the set of principles you are working from. Always approach projects with Relationality, Respect, Reciprocity, and Responsibility at the forefront of your mind.

Other Frameworks for Indigenous Self-Determination and Good Research Practices

- Canada: National Inuit Strategy on Research (2018), Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

- Note: to the best knowledge of the authors, a framework from the Métis Nations does not exist currently.

- Australia: Communique (2018), Maiam nayri Wingara

- New Zealand: Principles of Maori Data Sovereignty (2018), Te Mana Raraunga

- Global: CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance (2019) Global Indigenous Data Alliance

Conclusion

This chapter has focused on the history and present-day iterations of knowledge theft and knowledge mining, including a history of the global political community of Indigenous Peoples, especially the impact of the United Nations Declaration on the Right of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in Canada. We have contextualized the importance of Indigenous data sovereignty within this history, and have shared best practices for working with Indigenous data in order to challenge historically bad data practices. These best practices include recommendations from the Principles of OCAP®, the strongest tool First Nations people in Canada and their allies have in asserting their sovereignty over data.

Reflective Questions

- Which assumption or consideration of reframing your research practices to incorporate Indigenous ways of knowing did you find most challenging? Why?

- Can you identify any strategies you could deploy in your own research to be respectful of the Principles of OCAP® or other principles for self-determination?

- Consider asking your institution to provide researchers the opportunity to complete the Fundamentals of OCAP® online training course or host the FNIGC to lead a workshop before you submit your next application to your research ethics board. If funding is not currently available, consider the following resources:

-

- Watch this brief video: Understanding the First Nations Principles of OCAP®: Our road map to information governance from First Nations Information Governance Centre (2014)

- Watch this conference presentation: First Nations data sovereignty and twenty five years of OCAP® with Aaron Franks, presented at the 2022 Canada Open Data Summit

- Explore this webpage: The First Nations Principles of OCAP®

- Print this brochure to keep around your workplace: The First Nations Principles of OCAP® from First Nations Information Governance Centre (2022)

- Read this document: Exploration of the impact of Canada’s information management regime on First Nations data sovereignty from First Nations Information Governance Centre (2022)

- Read this document: Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAP®): The path to First Nations information governance from FNIGC (2014)

- Print this infographic: Indigenous Peoples’ rights in data from Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA) (2022)

- Explore this presentation: Indigenous data sovereignty and governance from GIDA (2022)

Key Takeaways

- Data gathered by colonial nation states “others” Indigenous Peoples by comparing them against an Anglo-colonized reality, which lacks social and cultural context, and focuses on social disadvantages and disparities. This makes the policies it informs invalid. Indigenous data sovereignty is crucial if the goal is to form valid and useful policies and programs.

- Researchers informed by Indigenous ways of knowing make different assumptions than those informed by Western ways of knowing. Indigenous researchers also ensure that their work is community-based, by centering relationality, respect, reciprocity, and responsibility.

- Good Indigenous data is self-determined, meaning that Indigenous Peoples own it, control it, determine who has access to it, and oversee its storage.

Additional Readings and Resources

Lovett, R. Lee, V., Kukutai, T., Cormack, D., Rainie, S. C., & Walker, J. (2019). Good data practices for Indigenous data sovereignty and governance. In A. Daly, S. K. Devitt, & M. Mann (Eds.), Good data (pp. 26-36). Institute of Network Cultures: Amsterdam.

Toombs, E., Drawson, A. S., Chambers, L., Bobinski, T. L. R., Dixon, J., & Mushquash, C. J. (2019). Moving towards an Indigenous research process: A reflexive approach to empirical work with First Nations communities in Canada. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2019.10.1.6

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples. University of Otago Press: Dunedin, New Zealand.

Reference List

Archibald, J.-A. (2008). Indigenous storywork: Educating the heart, mind, body, and spirit. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Erueti, A. (2022). The UN declaration on the rights of Indigenous Peoples: A new interpretative approach. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

First Nations Centre. (1997). First Nations and Inuit Regional Health Surveys, 1997. https://fnigc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/71d4e0eb1219747e7762df4f6a133a3d_rhs_1997_synthesis_report.pdf

First Nations Information Governance Centre. (2022a). Our history. https://fnigc.ca/about-fnigc/our-history/#slide-1

First Nations Information Governance Centre. (2022b). The First Nations Principles of OCAP. https://fnigc.ca/ocap-training/

First Nations Information Governance Centre. (2016). Pathways to First Nations’ data and information sovereignty. In T. Kukutai, & J. Taylor (Eds.), Indigenous data sovereignty: Toward an agenda, (pp. 139-156). Canberra, Australia: ANU Press.

First Nations Information Governance Centre. (2014, July 22). Understanding the First Nations Principles of OCAP: Our road map to information governance [Video]. Youtube. https://youtu.be/y32aUFVfCM0

Hanson, E. (n.d-a.). ILO convention 107. UBC Indigenous Foundations. Retrieved April 17, 2022, from https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/ilo_convention_107/

Hanson, E. (n.d-b.). ILO convention 169. UBC Indigenous Foundations. Retrieved April 17, 2022, from https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/ilo_convention_169/

Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development. (2006). Review of the First Nations regional longitudinal health survey (RHS) 2002/2003. https://fnigc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/67736a68b4f311bfbf07b0a4906c069a_rhs_harvard_independent_review.pdf

Holm, T., Pearson, J. D., & Chavis, B. (2003). Peoplehood: A model for the extension of sovereignty in American Indian studies. Wicazo Sa Review, 18(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1353/wic.2003.0004

Kidwell, C. S. (1993). Systems of Knowledge. In A. M. Josephy & F. E. Hoxie (Eds.), America in 1492: The world of the Indian peoples before the arrival of Columbus, (pp. 369–403). Vintage Books.

Indigenous Services Canada. (2022). Mandate. https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1539284416739/1539284508506

Littletree, S., Belarde-Lewis, M., & Duarte, M. (2020). Centering relationality: A conceptual model to advance Indigenous knowledge organization practices. Knowledge Organization, 47(5), 410-426. https://doi.org/10.5771/0943-7444-2020-5-410

Meyer, M. A. (2008). Indigenous and authentic: Hawaiian epistemology and the triangulation of meaning. In N. K. Denzin, Y. S. Lincoln, & L. T. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies, (pp. 217–232). Sage.

National Aboriginal Health Organization. (2005). Ownership, control, access, and possession (OCAP) or self-determination applied to research: A critical analysis of contemporary First Nations research and some options for First Nations communities. https://ruor.uottawa.ca/bitstream/10393/30539/1/OCAP_Critical_Analysis_2005.pdf

National Indigenous Australians Agency (2022). Closing the gap. https://www.niaa.gov.au/Indigenous-affairs/closing-gap

Schnarch, B. (2005). A critical analysis of contemporary First Nations research and some options for First Nations communities. Journal of Aboriginal Health, 1(1), 80-95. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/ijih/article/view/28934

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. (2017). https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf

United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs (2023). Mission statement. https://www.bia.gov/bia

Walter, M. (2016). Data politics and Indigenous representation in Australian statistics. In T. Kukutai & J. Taylor (Eds.), Indigenous data sovereignty: Toward an agenda, (pp. 79-87). Canberra, Australia: ANU Press.

Walter, M. (2018). The voice of indigenous data: Beyond the markers of disadvantage. Griffith Review, 60, 256–263.

Walter, M., & Andersen, C. (2013). Indigenous statistics: A quantitative research methodology. Routledge: Walnut Creek.

Walter, M., Kukutai, T., Russo Carroll, S., & Rodriguez-Lonebear, D. (2021). Indigenous data sovereignty and policy. Taylor & Francis: Milton.

Walter, M., & Suina, M. (2019). Indigenous data, Indigenous methodologies, and Indigenous data sovereignty. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 22(3), 233-243. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2018.1531228

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Publishing: Halifax.

collecting Indigenous knowledge without seeking permission or consulting stakeholders in the community.

collecting Indigenous knowledge without seeking permission or consulting stakeholders in the community.

the right of Indigenous Peoples to determine what is best for their social, cultural, and economic development, and to carry out those decisions in a way that is best for their people. This definition is based on the United Nations Declaration on the Right of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

the right of Indigenous Peoples to collect, access, analyze, interpret, manage, distribute, and reuse all data that was derived from or relates to their communities.

collective knowledge of the traditions and practices that were developed over time and used by Indigenous groups to sustain themselves and adapt to their environment. Traditional knowledge is passed from one generation to the next within Indigenous communities. Indigenous knowledge comes in many forms including, storytelling, ceremony, dance, arts, crafts, hunting, trapping, gathering, food preparation and storage, spirituality, beliefs and worldviews, and plant medicines.

an acronym for ownership, control, access, and possession. These four principles govern how First Nations data and information should be collected, protected, used, and shared. OCAP® was created because Western laws do not recognize the community rights of Indigenous Peoples to control their information.

a formal description of what a researcher plans to do with their data from collection to eventual disposal or deletion.