The Thyroid Gland

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the location and anatomy of the thyroid gland

- Discuss the synthesis of triiodothyronine and thyroxine

- Explain the role of thyroid hormones in the regulation of basal metabolism

- Identify the hormone produced by the parafollicular cells of the thyroid

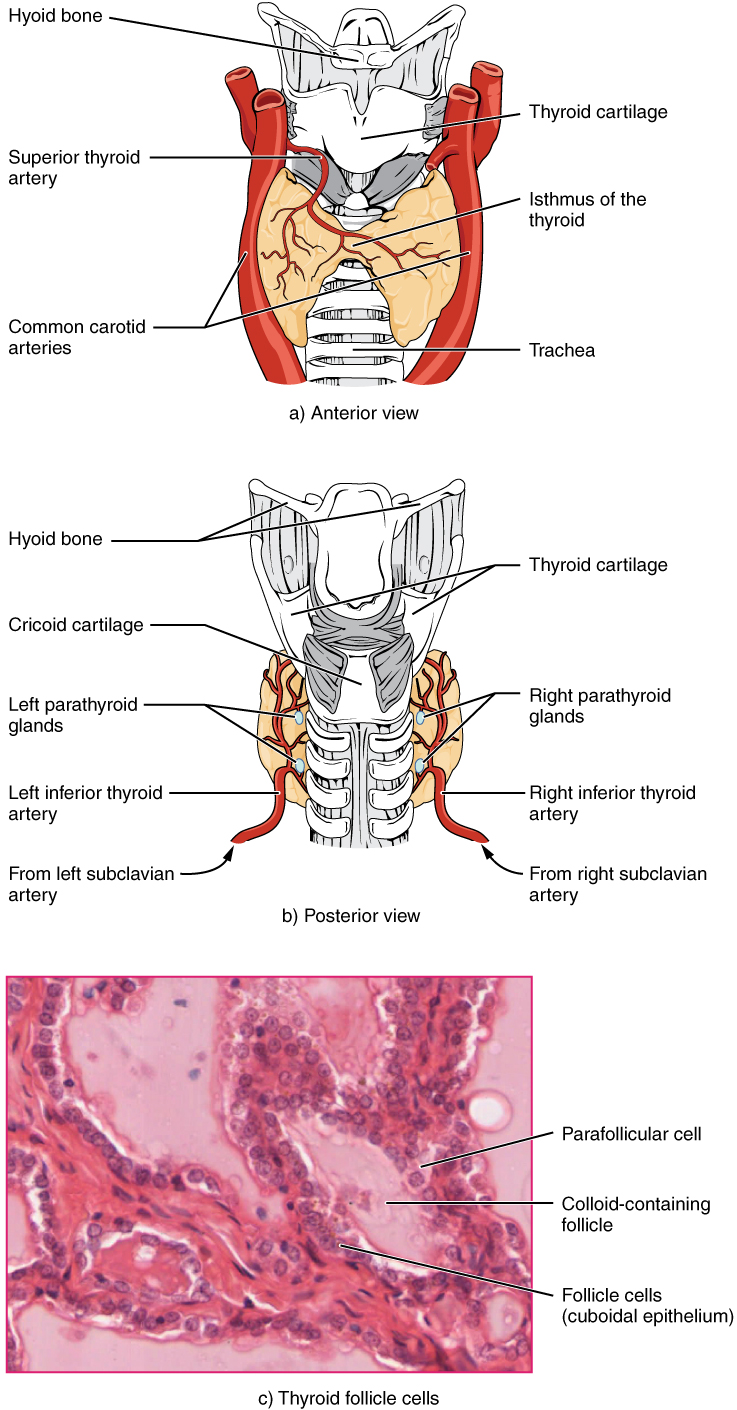

A butterfly-shaped organ, the thyroid gland is located anterior to the trachea, just inferior to the larynx (Figure 17.12). The medial region, called the isthmus, is flanked by wing-shaped left and right lobes. Each of the thyroid lobes are embedded with parathyroid glands, primarily on their posterior surfaces. The tissue of the thyroid gland is composed mostly of thyroid follicles. The follicles are made up of a central cavity filled with a sticky fluid called colloid. Surrounded by a wall of epithelial follicle cells, the colloid is the center of thyroid hormone production, and that production is dependent on the hormones’ essential and unique component: iodine.

Figure 17.12 Thyroid Gland The thyroid gland is located in the neck where it wraps around the trachea. (a) Anterior view of the thyroid gland. (b) Posterior view of the thyroid gland. (c) The glandular tissue is composed primarily of thyroid follicles. The larger parafollicular cells often appear within the matrix of follicle cells. LM × 1332. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

Figure 17.12 Thyroid Gland The thyroid gland is located in the neck where it wraps around the trachea. (a) Anterior view of the thyroid gland. (b) Posterior view of the thyroid gland. (c) The glandular tissue is composed primarily of thyroid follicles. The larger parafollicular cells often appear within the matrix of follicle cells. LM × 1332. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

Synthesis and Release of Thyroid Hormones

Hormones are produced in the colloid when atoms of the mineral iodine attach to a glycoprotein, called thyroglobulin, that is secreted into the colloid by the follicle cells. The following steps outline the hormones’ assembly:

- Binding of TSH to its receptors in the follicle cells of the thyroid gland causes the cells to actively transport iodide ions (I–) across their cell membrane, from the bloodstream into the cytosol. As a result, the concentration of iodide ions “trapped” in the follicular cells is many times higher than the concentration in the bloodstream.

- Iodide ions then move to the lumen of the follicle cells that border the colloid. There, the ions undergo oxidation (their negatively charged electrons are removed). The oxidation of two iodide ions (2 I–) results in iodine (I2), which passes through the follicle cell membrane into the colloid.

- In the colloid, peroxidase enzymes link the iodine to the tyrosine amino acids in thyroglobulin to produce two intermediaries: a tyrosine attached to one iodine and a tyrosine attached to two iodines. When one of each of these intermediaries is linked by covalent bonds, the resulting compound is triiodothyronine (T3), a thyroid hormone with three iodines. Much more commonly, two copies of the second intermediary bond, forming tetraiodothyronine, also known as thyroxine (T4), a thyroid hormone with four iodines.

These hormones remain in the colloid center of the thyroid follicles until TSH stimulates endocytosis of colloid back into the follicle cells. There, lysosomal enzymes break apart the thyroglobulin colloid, releasing free T3 and T4, which diffuse across the follicle cell membrane and enter the bloodstream.

In the bloodstream, less than one percent of the circulating T3 and T4 remains unbound. This free T3 and T4 can cross the lipid bilayer of cell membranes and be taken up by cells. The remaining 99 percent of circulating T3 and T4 is bound to specialized transport proteins called thyroxine-binding globulins (TBGs), to albumin, or to other plasma proteins. This “packaging” prevents their free diffusion into body cells. When blood levels of T3 and T4 begin to decline, bound T3 and T4 are released from these plasma proteins and readily cross the membrane of target cells. T3 is more potent than T4, and many cells convert T4 to T3 through the removal of an iodine atom.

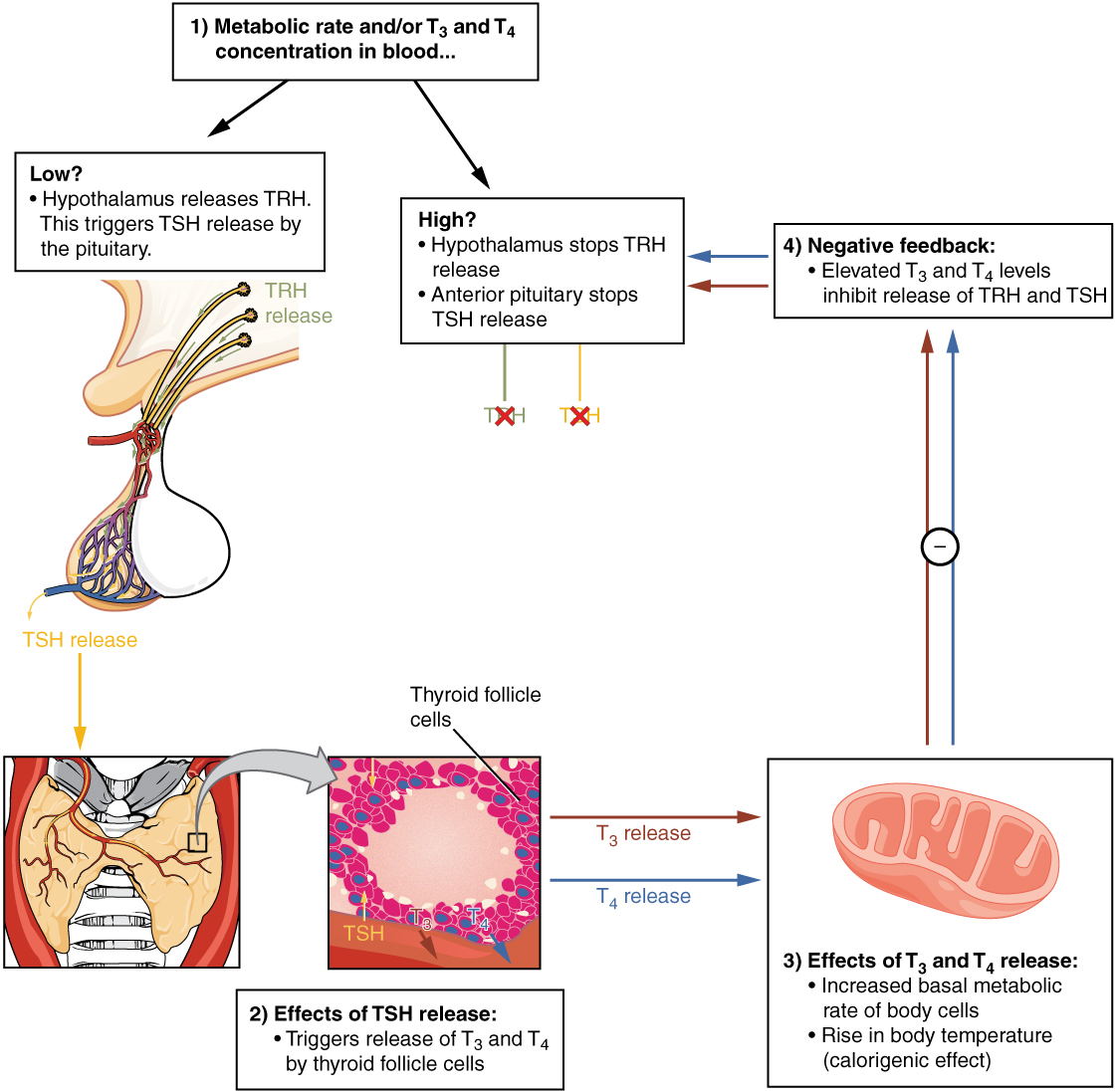

Regulation of TH Synthesis

The release of T3 and T4 from the thyroid gland is regulated by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). As shown in Figure 17.13, low blood levels of T3 and T4 stimulate the release of thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) from the hypothalamus, which triggers secretion of TSH from the anterior pituitary. In turn, TSH stimulates the thyroid gland to secrete T3 and T4. The levels of TRH, TSH, T3, and T4 are regulated by a negative feedback system in which increasing levels of T3 and T4 decrease the production and secretion of TSH.

Figure 17.13 Classic Negative Feedback Loop A classic negative feedback loop controls the regulation of thyroid hormone levels.

Figure 17.13 Classic Negative Feedback Loop A classic negative feedback loop controls the regulation of thyroid hormone levels.

Functions of Thyroid Hormones

The thyroid hormones, T3 and T4, are often referred to as metabolic hormones because their levels influence the body’s basal metabolic rate, the amount of energy used by the body at rest. When T3 and T4 bind to intracellular receptors located on the mitochondria, they cause an increase in nutrient breakdown and the use of oxygen to produce ATP. In addition, T3 and T4 initiate the transcription of genes involved in glucose oxidation. Although these mechanisms prompt cells to produce more ATP, the process is inefficient, and an abnormally increased level of heat is released as a byproduct of these reactions. This so-called calorigenic effect (calor- = “heat”) raises body temperature.

Adequate levels of thyroid hormones are also required for protein synthesis and for fetal and childhood tissue development and growth. They are especially critical for normal development of the nervous system both in utero and in early childhood, and they continue to support neurological function in adults. As noted earlier, these thyroid hormones have a complex interrelationship with reproductive hormones, and deficiencies can influence libido, fertility, and other aspects of reproductive function. Finally, thyroid hormones increase the body’s sensitivity to catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) from the adrenal medulla by upregulation of receptors in the blood vessels. When levels of T3 and T4 hormones are excessive, this effect accelerates the heart rate, strengthens the heartbeat, and increases blood pressure. Because thyroid hormones regulate metabolism, heat production, protein synthesis, and many other body functions, thyroid disorders can have severe and widespread consequences.

DISORDERS OF THE …

Endocrine System: Iodine Deficiency, Hypothyroidism, and Hyperthyroidism

As discussed above, dietary iodine is required for the synthesis of T3 and T4. But for much of the world’s population, foods do not provide adequate levels of this mineral, because the amount varies according to the level in the soil in which the food was grown, as well as the irrigation and fertilizers used. Marine fish and shrimp tend to have high levels because they concentrate iodine from seawater, but many people in landlocked regions lack access to seafood. Thus, the primary source of dietary iodine in many countries is iodized salt. Fortification of salt with iodine began in the United States in 1924, and international efforts to iodize salt in the world’s poorest nations continue today.

Dietary iodine deficiency can result in the impaired ability to synthesize T3 and T4, leading to a variety of severe disorders. When T3 and T4 cannot be produced, TSH is secreted in increasing amounts. As a result of this hyperstimulation, thyroglobulin accumulates in the thyroid gland follicles, increasing their deposits of colloid. The accumulation of colloid increases the overall size of the thyroid gland, a condition called a goiter (Figure 17.14). A goiter is only a visible indication of the deficiency. Other iodine deficiency disorders include impaired growth and development, decreased fertility, and prenatal and infant death. Moreover, iodine deficiency is the primary cause of preventable intellectual disabilies worldwide. Neonatal hypothyroidism (cretinism) is characterized by cognitive deficits, short stature, and sometimes deafness and muteness in children and adults born to mothers who were iodine-deficient during pregnancy.

Figure 17.14 Goiter (credit: “Almazi”/Wikimedia Commons)

Figure 17.14 Goiter (credit: “Almazi”/Wikimedia Commons)

In areas of the world with access to iodized salt, dietary deficiency is rare. Instead, inflammation of the thyroid gland is the more common cause of low blood levels of thyroid hormones. Called hypothyroidism, the condition is characterized by a low metabolic rate, weight gain, cold extremities, constipation, reduced libido, menstrual irregularities, and reduced mental activity. In contrast, hyperthyroidism—an abnormally elevated blood level of thyroid hormones—is often caused by a pituitary or thyroid tumor. In Graves’ disease, the hyperthyroid state results from an autoimmune reaction in which antibodies overstimulate the follicle cells of the thyroid gland. Hyperthyroidism can lead to an increased metabolic rate, excessive body heat and sweating, diarrhea, weight loss, tremors, and increased heart rate. The person’s eyes may bulge (called exophthalmos) as antibodies produce inflammation in the soft tissues of the orbits. The person may also develop a goiter.

Calcitonin

The thyroid gland also secretes a hormone called calcitonin that is produced by the parafollicular cells (also called C cells) that stud the tissue between distinct follicles. Calcitonin is released in response to a rise in blood calcium levels. It appears to have a function in decreasing blood calcium concentrations by:

- Inhibiting the activity of osteoclasts, bone cells that release calcium into the circulation by degrading bone matrix

- Increasing osteoblastic activity

- Decreasing calcium absorption in the intestines

- Increasing calcium loss in the urine

However, these functions are usually not significant in maintaining calcium homeostasis, so the importance of calcitonin is not entirely understood. Pharmaceutical preparations of calcitonin are sometimes prescribed to reduce osteoclast activity in people with osteoporosis and to reduce the degradation of cartilage in people with osteoarthritis. The hormones secreted by thyroid are summarized in Table 17.4.

Thyroid Hormones

Associated hormones |

Chemical class |

Effect |

Thyroxine (T4), triiodothyronine (T3) |

Amine |

Stimulate basal metabolic rate |

Calcitonin |

Peptide |

Reduces blood Ca2+ levels |

Table 17.4

Of course, calcium is critical for many other biological processes. It is a second messenger in many signaling pathways, and is essential for muscle contraction, nerve impulse transmission, and blood clotting. Given these roles, it is not surprising that blood calcium levels are tightly regulated by the endocrine system. The organs involved in the regulation are the parathyroid glands.