The Endocrine Pancreas

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the location and structure of the pancreas, and the morphology and function of the pancreatic islets

- Compare and contrast the functions of insulin and glucagon

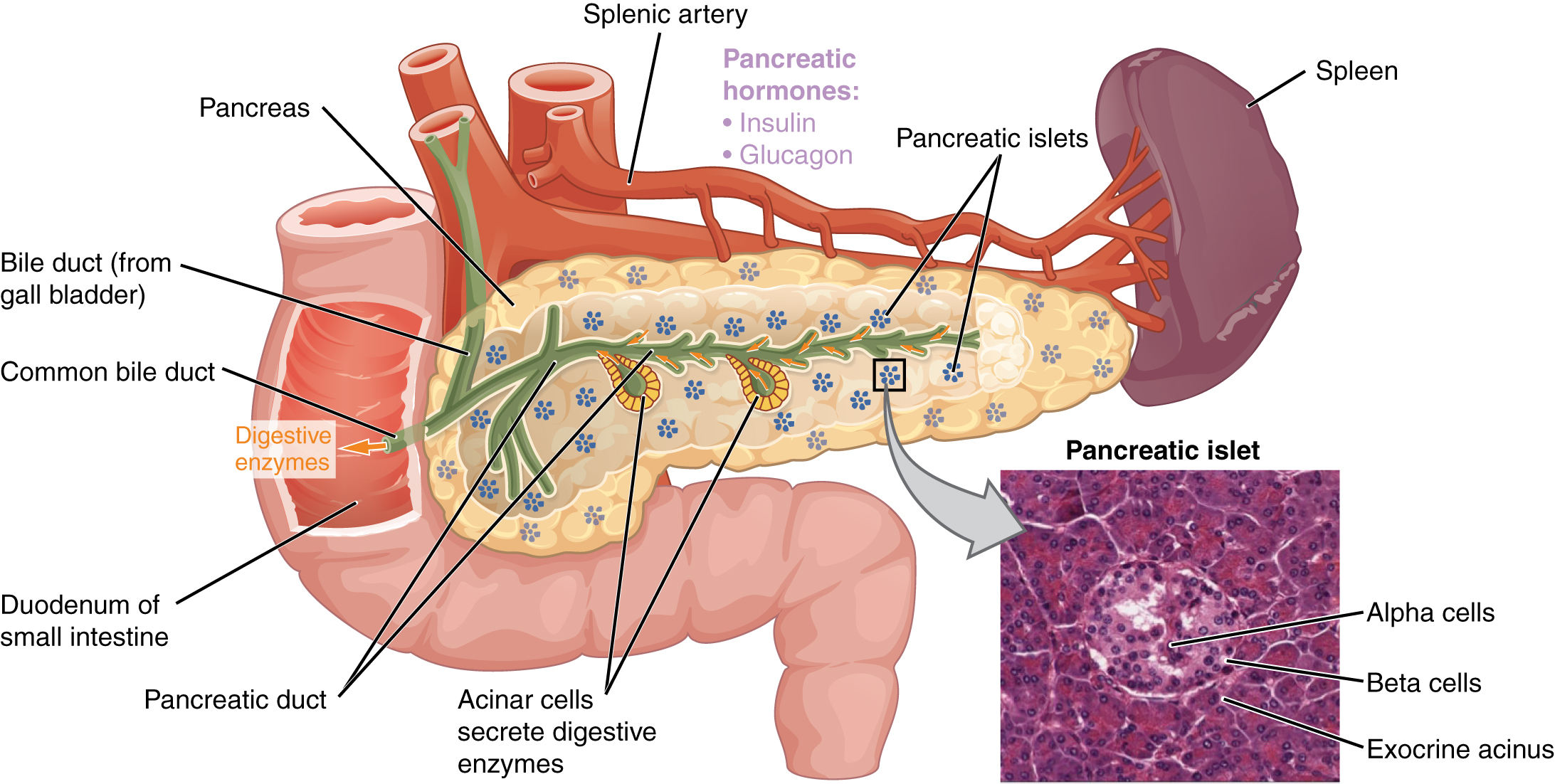

The pancreas is a long, slender organ, most of which is located posterior to the bottom half of the stomach (Figure 17.18). Although it is primarily an exocrine gland, secreting a variety of digestive enzymes, the pancreas has an endocrine function. Its pancreatic islets—clusters of cells formerly known as the islets of Langerhans—secrete the hormones glucagon, insulin, somatostatin, and pancreatic polypeptide (PP).

Figure 17.18 Pancreas The pancreatic exocrine function involves the acinar cells secreting digestive enzymes that are transported into the small intestine by the pancreatic duct. Its endocrine function involves the secretion of insulin (produced by beta cells) and glucagon (produced by alpha cells) within the pancreatic islets. These two hormones regulate the rate of glucose metabolism in the body. The micrograph reveals pancreatic islets. LM × 760. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

Figure 17.18 Pancreas The pancreatic exocrine function involves the acinar cells secreting digestive enzymes that are transported into the small intestine by the pancreatic duct. Its endocrine function involves the secretion of insulin (produced by beta cells) and glucagon (produced by alpha cells) within the pancreatic islets. These two hormones regulate the rate of glucose metabolism in the body. The micrograph reveals pancreatic islets. LM × 760. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

INTERACTIVE LINK

View the University of Michigan WebScope to explore the tissue sample in greater detail.

Cells and Secretions of the Pancreatic Islets

The pancreatic islets each contain four varieties of cells:

- The alpha cell produces the hormone glucagon and makes up approximately 20 percent of each islet. Glucagon plays an important role in blood glucose regulation; low blood glucose levels stimulate its release.

- The beta cell produces the hormone insulin and makes up approximately 75 percent of each islet. Elevated blood glucose levels stimulate the release of insulin.

- The delta cell accounts for four percent of the islet cells and secretes the peptide hormone somatostatin. Recall that somatostatin is also released by the hypothalamus (as GHIH), and the stomach and intestines also secrete it. An inhibiting hormone, pancreatic somatostatin inhibits the release of both glucagon and insulin.

- The PP cell accounts for about one percent of islet cells and secretes the pancreatic polypeptide hormone. It is thought to play a role in appetite, as well as in the regulation of pancreatic exocrine and endocrine secretions. Pancreatic polypeptide released following a meal may reduce further food consumption; however, it is also released in response to fasting.

Regulation of Blood Glucose Levels by Insulin and Glucagon

Glucose is required for cellular respiration and is the preferred fuel for all body cells. The body derives glucose from the breakdown of the carbohydrate-containing foods and drinks we consume. Glucose not immediately taken up by cells for fuel can be stored by the liver and muscles as glycogen, or converted to triglycerides and stored in the adipose tissue. Hormones regulate both the storage and the utilization of glucose as required. Receptors located in the pancreas sense blood glucose levels, and subsequently the pancreatic cells secrete glucagon or insulin to maintain normal levels.

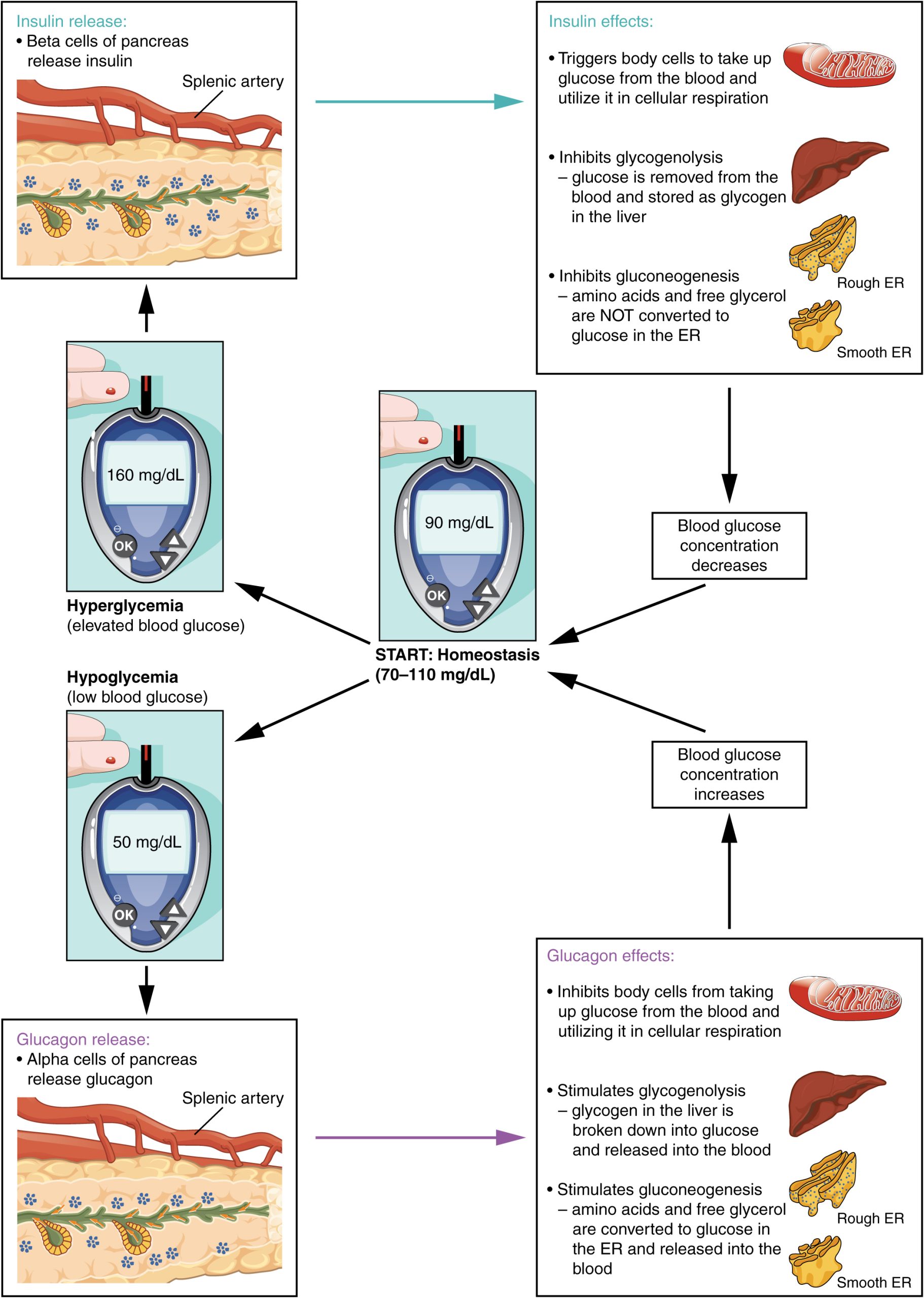

Glucagon

Receptors in the pancreas can sense the decline in blood glucose levels, such as during periods of fasting or during prolonged labor or exercise (Figure 17.19). In response, the alpha cells of the pancreas secrete the hormone glucagon, which has several effects:

- It stimulates the liver to convert its stores of glycogen back into glucose. This response is known as glycogenolysis. The glucose is then released into the circulation for use by body cells.

- It stimulates the liver to take up amino acids from the blood and convert them into glucose. This response is known as gluconeogenesis.

- It stimulates lipolysis, the breakdown of stored triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol. Some of the free glycerol released into the bloodstream travels to the liver, which converts it into glucose. This is also a form of gluconeogenesis.

Taken together, these actions increase blood glucose levels. The activity of glucagon is regulated through a negative feedback mechanism; rising blood glucose levels inhibit further glucagon production and secretion.

Figure 17.19 Homeostatic Regulation of Blood Glucose Levels Blood glucose concentration is tightly maintained between 70 mg/dL and 110 mg/dL. If blood glucose concentration rises above this range, insulin is released, which stimulates body cells to remove glucose from the blood. If blood glucose concentration drops below this range, glucagon is released, which stimulates body cells to release glucose into the blood.

Figure 17.19 Homeostatic Regulation of Blood Glucose Levels Blood glucose concentration is tightly maintained between 70 mg/dL and 110 mg/dL. If blood glucose concentration rises above this range, insulin is released, which stimulates body cells to remove glucose from the blood. If blood glucose concentration drops below this range, glucagon is released, which stimulates body cells to release glucose into the blood.

Insulin

The primary function of insulin is to facilitate the uptake of glucose into body cells. Red blood cells, as well as cells of the brain, liver, kidneys, and the lining of the small intestine, do not have insulin receptors on their cell membranes and do not require insulin for glucose uptake. Although all other body cells do require insulin if they are to take glucose from the bloodstream, skeletal muscle cells and adipose cells are the primary targets of insulin.

The presence of food in the intestine triggers the release of gastrointestinal tract hormones such as glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (previously known as gastric inhibitory peptide). This is in turn the initial trigger for insulin production and secretion by the beta cells of the pancreas. Once nutrient absorption occurs, the resulting surge in blood glucose levels further stimulates insulin secretion.

Precisely how insulin facilitates glucose uptake is not entirely clear. However, insulin appears to activate a tyrosine kinase receptor, triggering the phosphorylation of many substrates within the cell. These multiple biochemical reactions converge to support the movement of intracellular vesicles containing facilitative glucose transporters to the cell membrane. In the absence of insulin, these transport proteins are normally recycled slowly between the cell membrane and cell interior. Insulin triggers the rapid movement of a pool of glucose transporter vesicles to the cell membrane, where they fuse and expose the glucose transporters to the extracellular fluid. The transporters then move glucose by facilitated diffusion into the cell interior.

INTERACTIVE LINK

Visit this link to view an animation describing the location and function of the pancreas. What goes wrong in the function of insulin in type 2 diabetes?

Insulin also reduces blood glucose levels by stimulating glycolysis, the metabolism of glucose for generation of ATP. Moreover, it stimulates the liver to convert excess glucose into glycogen for storage, and it inhibits enzymes involved in glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. Finally, insulin promotes triglyceride and protein synthesis. The secretion of insulin is regulated through a negative feedback mechanism. As blood glucose levels decrease, further insulin release is inhibited. The pancreatic hormones are summarized in Table 17.7.

Hormones of the Pancreas

Associated hormones |

Chemical class |

Effect |

Insulin (beta cells) |

Protein |

Reduces blood glucose levels |

Glucagon (alpha cells) |

Protein |

Increases blood glucose levels |

Somatostatin (delta cells) |

Protein |

Inhibits insulin and glucagon release |

Pancreatic polypeptide (PP cells) |

Protein |

Role in appetite |

Table 17.7

DISORDERS OF THE …

Endocrine System: Diabetes Mellitus

Dysfunction of insulin production and secretion, as well as the target cells’ responsiveness to insulin, can lead to a condition called diabetes mellitus. An increasingly common disease, diabetes mellitus has been diagnosed in more than 18 million adults in the United States, and more than 200,000 children. It is estimated that up to 7 million more adults have the condition but have not been diagnosed. In addition, approximately 79 million people in the US are estimated to have pre-diabetes, a condition in which blood glucose levels are abnormally high, but not yet high enough to be classified as diabetes.

There are two main forms of diabetes mellitus. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease affecting the beta cells of the pancreas. Certain genes are recognized to increase susceptibility. The beta cells of people with type 1 diabetes do not produce insulin; thus, synthetic insulin must be administered by injection or infusion. This form of diabetes accounts for less than five percent of all diabetes cases.

Type 2 diabetes accounts for approximately 95 percent of all cases. It is acquired, and lifestyle factors such as poor diet, inactivity, and the presence of pre-diabetes greatly increase a person’s risk. About 80 to 90 percent of people with type 2 diabetes are overweight or obese. In type 2 diabetes, cells become resistant to the effects of insulin. In response, the pancreas increases its insulin secretion, but over time, the beta cells become exhausted. In many cases, type 2 diabetes can be reversed by moderate weight loss, regular physical activity, and consumption of a healthy diet; however, if blood glucose levels cannot be controlled, the person with diabetes will eventually require insulin.

Two of the early manifestations of diabetes are excessive urination and excessive thirst. They demonstrate how the out-of-control levels of glucose in the blood affect kidney function. The kidneys are responsible for filtering glucose from the blood. Excessive blood glucose draws water into the urine, and as a result the person eliminates an abnormally large quantity of sweet urine. The use of body water to dilute the urine leaves the body dehydrated, and so the person is unusually and continually thirsty. The person may also experience persistent hunger because the body cells are unable to access the glucose in the bloodstream.

Over time, persistently high levels of glucose in the blood injure tissues throughout the body, especially those of the blood vessels and nerves. Inflammation and injury of the lining of arteries lead to atherosclerosis and an increased risk of heart attack and stroke. Damage to the microscopic blood vessels of the kidney impairs kidney function and can lead to kidney failure. Damage to blood vessels that serve the eyes can lead to blindness. Blood vessel damage also reduces circulation to the limbs, whereas nerve damage leads to a loss of sensation, called neuropathy, particularly in the hands and feet. Together, these changes increase the risk of injury, infection, and tissue death (necrosis), contributing to a high rate of toe, foot, and lower leg amputations in people with diabetes. Uncontrolled diabetes can also lead to a dangerous form of metabolic acidosis called ketoacidosis. Deprived of glucose, cells increasingly rely on fat stores for fuel. However, in a glucose-deficient state, the liver is forced to use an alternative lipid metabolism pathway that results in the increased production of ketone bodies (or ketones), which are acidic. The build-up of ketones in the blood causes ketoacidosis, which—if left untreated—may lead to a life-threatening “diabetic coma.” Together, these complications make diabetes the seventh leading cause of death in the United States.

Diabetes is diagnosed when lab tests reveal that blood glucose levels are higher than normal, a condition called hyperglycemia. The treatment of diabetes depends on the type, the severity of the condition, and the ability of the patient to make lifestyle changes. As noted earlier, moderate weight loss, regular physical activity, and consumption of a healthful diet can reduce blood glucose levels. Some patients with type 2 diabetes may be unable to control their disease with these lifestyle changes, and will require medication. Historically, the first-line treatment of type 2 diabetes was insulin. Research advances have resulted in alternative options, including medications that enhance pancreatic function.

INTERACTIVE LINK

Visit this link to view an animation describing the role of insulin and the pancreas in diabetes.