Transplantation and Cancer Immunology

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain why blood typing is important and what happens when mismatched blood is used in a transfusion

- Describe how tissue typing is done during organ transplantation and the role of transplant anti-rejection drugs

- Show how the immune response is able to control some cancers and how this immune response might be enhanced by cancer vaccines

The immune responses to transplanted organs and to cancer cells are both important medical issues. With the use of tissue typing and anti-rejection drugs, transplantation of organs and the control of the anti-transplant immune response have made huge strides in the past 50 years. Today, these procedures are commonplace. Tissue typing is the determination of MHC molecules in the tissue to be transplanted to better match the donor to the recipient. The immune response to cancer, on the other hand, has been more difficult to understand and control. Although it is clear that the immune system can recognize some cancers and control them, others seem to be resistant to immune mechanisms.

The Rh Factor

Red blood cells can be typed based on their surface antigens. ABO blood type, in which individuals are type A, B, AB, or O according to their genetics, is one example. A separate antigen system seen on red blood cells is the Rh antigen. When someone is “A positive” for example, the positive refers to the presence of the Rh antigen, whereas someone who is “A negative” would lack this molecule.

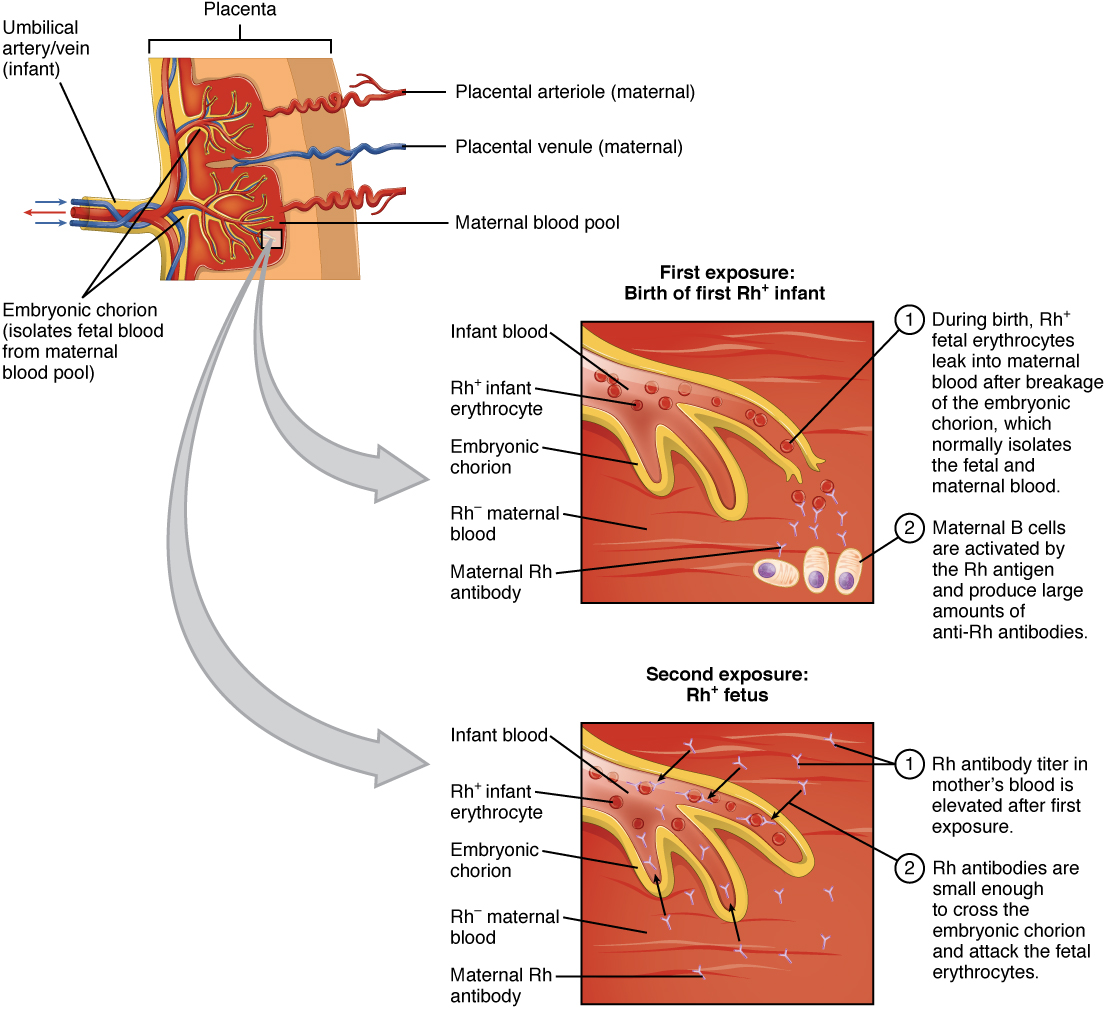

An interesting consequence of Rh factor expression is seen in erythroblastosis fetalis, a hemolytic disease of the newborn (Figure 21.30). This disease occurs when people negative for Rh antigen have multiple Rh-positive children. During the birth of a first Rh-positive child, the birth parent makes a primary anti-Rh antibody response to the fetal blood cells that enter the pregnant person’s bloodstream. If the same parent has a second Rh-positive child, IgG antibodies against Rh-positive blood mounted during this secondary response cross the placenta and attack the fetal blood, causing anemia. This is a consequence of the fact that the fetus is not genetically identical to the birth parent, and thus the parent is capable of mounting an immune response against it. This disease is treated with antibodies specific for Rh factor. These are given to the pregnant person during the first and subsequent births, destroying any fetal blood that might enter their system and preventing the immune response.

Figure 21.30 Erythroblastosis Fetalis Erythroblastosis fetalis (hemolytic disease of the newborn) is the result of an immune response in an Rh-negative person who has multiple children with an Rh-positive person. During the first birth, fetal blood enters the pregnant person’s circulatory system, and anti-Rh antibodies are made. During the gestation of the second child, these antibodies cross the placenta and attack the blood of the fetus. The treatment for this disease is to give the carrier anti-Rh antibodies (RhoGAM) during the first pregnancy to destroy Rh-positive fetal red blood cells from entering their system and causing the anti-Rh antibody response in the first place.

Figure 21.30 Erythroblastosis Fetalis Erythroblastosis fetalis (hemolytic disease of the newborn) is the result of an immune response in an Rh-negative person who has multiple children with an Rh-positive person. During the first birth, fetal blood enters the pregnant person’s circulatory system, and anti-Rh antibodies are made. During the gestation of the second child, these antibodies cross the placenta and attack the blood of the fetus. The treatment for this disease is to give the carrier anti-Rh antibodies (RhoGAM) during the first pregnancy to destroy Rh-positive fetal red blood cells from entering their system and causing the anti-Rh antibody response in the first place.

Tissue Transplantation

Tissue transplantation is more complicated than blood transfusions because of two characteristics of MHC molecules. These molecules are the major cause of transplant rejection (hence the name “histocompatibility”). MHC polygeny refers to the multiple MHC proteins on cells, and MHC polymorphism refers to the multiple alleles for each individual MHC locus. Thus, there are many alleles in the human population that can be expressed (Table 21.8 and Table 21.9). When a donor organ expresses MHC molecules that are different from the recipient, the latter will often mount a cytotoxic T cell response to the organ and reject it. Histologically, if a biopsy of a transplanted organ exhibits massive infiltration of T lymphocytes within the first weeks after transplant, it is a sign that the transplant is likely to fail. The response is a classical, and very specific, primary T cell immune response. As far as medicine is concerned, the immune response in this scenario does the patient no good at all and causes significant harm.

Partial Table of Alleles of the Human MHC (Class I)

Gene |

# of alleles |

# of possible MHC I protein components |

A |

2132 |

1527 |

B |

2798 |

2110 |

C |

1672 |

1200 |

E |

11 |

3 |

F |

22 |

4 |

G |

50 |

16 |

Table 21.8

Partial Table of Alleles of the Human MHC (Class II)

Gene |

# of alleles |

# of possible MHC II protein components |

DRA |

7 |

2 |

DRB |

1297 |

958 |

DQA1 |

49 |

31 |

DQB1 |

179 |

128 |

DPA1 |

36 |

18 |

DPB1 |

158 |

136 |

DMA |

7 |

4 |

DMB |

13 |

7 |

DOA |

12 |

3 |

DOB |

13 |

5 |

Table 21.9

Immunosuppressive drugs such as cyclosporine A have made transplants more successful, but matching the MHC molecules is still key. In humans, there are six MHC molecules that show the most polymorphisms, three class I molecules (A, B, and C) and three class II molecules called DP, DQ, and DR. A successful transplant usually requires a match between at least 3–4 of these molecules, with more matches associated with greater success. Family members, since they share a similar genetic background, are much more likely to share MHC molecules than unrelated individuals do. In fact, due to the extensive polymorphisms in these MHC molecules, unrelated donors are found only through a worldwide database. The system is not foolproof however, as there are not enough individuals in the system to provide the organs necessary to treat all patients needing them.

One disease of transplantation occurs with bone marrow transplants, which are used to treat various diseases, including SCID and leukemia. Because the bone marrow cells being transplanted contain lymphocytes capable of mounting an immune response, and because the recipient’s immune response has been destroyed before receiving the transplant, the donor cells may attack the recipient tissues, causing graft-versus-host disease. Symptoms of this disease, which usually include a rash and damage to the liver and mucosa, are variable, and attempts have been made to moderate the disease by first removing mature T cells from the donor bone marrow before transplanting it.

Immune Responses Against Cancer

It is clear that with some cancers, for example Kaposi’s sarcoma, a healthy immune system does a good job at controlling them (Figure 21.31). This disease, which is caused by the human herpesvirus, is almost never observed in individuals with strong immune systems, such as the young and immunocompetent. Other examples of cancers caused by viruses include liver cancer caused by the hepatitis B virus and cervical cancer caused by the human papilloma virus. As these last two viruses have vaccines available for them, getting vaccinated can help prevent these two types of cancer by stimulating the immune response.

Figure 21.31 Karposi’s Sarcoma Lesions (credit: National Cancer Institute)

Figure 21.31 Karposi’s Sarcoma Lesions (credit: National Cancer Institute)

On the other hand, as cancer cells are often able to divide and mutate rapidly, they may escape the immune response, just as certain pathogens such as HIV do. There are three stages in the immune response to many cancers: elimination, equilibrium, and escape. Elimination occurs when the immune response first develops toward tumor-specific antigens specific to the cancer and actively kills most cancer cells, followed by a period of controlled equilibrium during which the remaining cancer cells are held in check. Unfortunately, many cancers mutate, so they no longer express any specific antigens for the immune system to respond to, and a subpopulation of cancer cells escapes the immune response, continuing the disease process.

This fact has led to extensive research in trying to develop ways to enhance the early immune response to completely eliminate the early cancer and thus prevent a later escape. One method that has shown some success is the use of cancer vaccines, which differ from viral and bacterial vaccines in that they are directed against the cells of one’s own body. Treated cancer cells are injected into cancer patients to enhance their anti-cancer immune response and thereby prolong survival. The immune system has the capability to detect these cancer cells and proliferate faster than the cancer cells do, overwhelming the cancer in a similar way as they do for viruses. Cancer vaccines have been developed for malignant melanoma, a highly fatal skin cancer, and renal (kidney) cell carcinoma. These vaccines are still in the development stages, but some positive and encouraging results have been obtained clinically.

It is tempting to focus on the complexity of the immune system and the problems it causes as a negative. The upside to immunity, however, is so much greater: The benefit of staying alive far outweighs the negatives caused when the system does sometimes go awry. Working on “autopilot,” the immune system helps to maintain your health and kill pathogens. The only time you really miss the immune response is when it is not being effective and illness results, or, as in the extreme case of HIV disease, the immune system is gone completely.

EVERYDAY CONNECTION

How Stress Affects the Immune Response: The Connections between the Immune, Nervous, and Endocrine Systems of the Body

The immune system cannot exist in isolation. After all, it has to protect the entire body from infection. Therefore, the immune system is required to interact with other organ systems, sometimes in complex ways. Thirty years of research focusing on the connections between the immune system, the central nervous system, and the endocrine system have led to a new science with the unwieldy name of called psychoneuroimmunology. The physical connections between these systems have been known for centuries: All primary and secondary organs are connected to sympathetic nerves. What is more complex, though, is the interaction of neurotransmitters, hormones, cytokines, and other soluble signaling molecules, and the mechanism of “crosstalk” between the systems. For example, white blood cells, including lymphocytes and phagocytes, have receptors for various neurotransmitters released by associated neurons. Additionally, hormones such as cortisol (naturally produced by the adrenal cortex) and prednisone (synthetic) are well known for their abilities to suppress T cell immune mechanisms, hence, their prominent use in medicine as long-term, anti-inflammatory drugs.

One well-established interaction of the immune, nervous, and endocrine systems is the effect of stress on immune health. In the human vertebrate evolutionary past, stress was associated with the fight-or-flight response, largely mediated by the central nervous system and the adrenal medulla. This stress was necessary for survival. The physical action of fighting or running, whichever the animal decides, usually resolves the problem in one way or another. On the other hand, there are no physical actions to resolve most modern day stresses, including short-term stressors like taking examinations and long-term stressors such as being unemployed or losing a spouse. The effect of stress can be felt by nearly every organ system, and the immune system is no exception (Table 21.10).

Effects of Stress on Body Systems

|

System |

Stress-related illness |

|

Integumentary system |

Acne, rashes, irritation |

|

Nervous system |

Headaches, depression, anxiety, irritability, loss of appetite, lack of motivation, reduced mental performance |

|

Muscular and skeletal systems |

Muscle and joint pain, neck and shoulder pain |

|

Circulatory system |

Increased heart rate, hypertension, increased probability of heart attacks |

|

Digestive system |

Indigestion, heartburn, stomach pain, nausea, diarrhea, constipation, weight gain or loss |

|

Immune system |

Depressed ability to fight infections |

|

Male reproductive system |

Lowered sperm production, impotence, reduced sexual desire |

|

Female reproductive system |

Irregular menstrual cycle, reduced sexual desire |

Table 21.10

At one time, it was assumed that all types of stress reduced all aspects of the immune response, but the last few decades of research have painted a different picture. First, most short-term stress does not impair the immune system in healthy individuals enough to lead to a greater incidence of diseases. However, older individuals and those with suppressed immune responses due to disease or immunosuppressive drugs may respond even to short-term stressors by getting sicker more often. It has been found that short-term stress diverts the body’s resources towards enhancing innate immune responses, which have the ability to act fast and would seem to help the body prepare better for possible infections associated with the trauma that may result from a fight-or-flight exchange. The diverting of resources away from the adaptive immune response, however, causes its own share of problems in fighting disease.

Chronic stress, unlike short-term stress, may inhibit immune responses even in otherwise healthy adults. The suppression of both innate and adaptive immune responses is clearly associated with increases in some diseases, as seen when individuals lose a spouse or have other long-term stresses, such as taking care of a spouse with a fatal disease or dementia. The new science of psychoneuroimmunology, while still in its relative infancy, has great potential to make exciting advances in our understanding of how the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems have evolved together and communicate with each other.