8 Management of Chronic Pain in Whiplash-associated Disorder

Claudia was assessed in a setting of comprehensive pain management. She was presented with the management options including trigger point injections, manual therapy plus exercise, and pain education. She questioned, “What is going to be gained; why be active? I have tried that but there you go … I am in so much pain.”

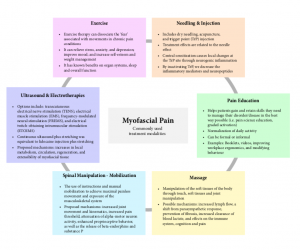

Evidence-informed approach suggests that an integration of at least three categories of treatments may be warranted in a comprehensive pain management setting (Figure 8-1):1

- Interventions aimed at decreasing pain signals or stimulus: medications and interventions.

- Interventions aimed at maintenance of activity: exercise and manual therapy.

- Other modalities aimed at managing pain: psychological and behavioral approaches (detailed in Chapter 9).

8.1 Pain Interventions

Interventional pain approaches help by achieving reduction of pain signals originating from a specific target or location. Besides the interventional approaches considered in Chapter 5, simple interventions focused on myofascial pain from the area can decrease pain severity, and in some patients improve function as well. They are considered below.

8.1.1. Needling and Injection: Dry Needling, Trigger Point Injections–Mechanism and Evidence

Dry needling, acupuncture, and trigger point injection fall within the spectrum of this modality.2

Although it was earlier considered that needling of trigger points requires an injection of treatment substance to be effective, later studies have shown that the subsequent treatment effects are related to the needle effect, rather than the injectate.3,4

Trigger points are discrete, focal, hyperirritable spots located in a skeletal muscle that has been injured or sensitized by the injury. Travell and Simons (well known for their book on myofascial pain syndrome),3 defined the myofascial trigger point as “a hyperirritable spot, usually within a taut band of skeletal muscle or in the muscle fascia, which is painful on compression and can give rise to characteristic referred pain, motor dysfunction, and autonomic phenomena”.4,5 Trigger points produce pain locally and also refer pain to other musculoskeletal structures, through their attachments. The etiology or the development of trigger points is not clear. It is theorized that they develop due to repetitive microtrauma, secondarily due to an underlying chronic pain condition.4,5 Studies using microdialysis catheter analysis have demonstrated a biochemical milieu of selected inflammatory mediators such as neuropeptides, cytokines, and catecholamines in active myofascial trigger points.6

Trigger points are referred to as active trigger points when they cause pain at rest and latent when they do not cause pain at rest. Latent trigger points can cause pain on deeper pressure. An active trigger point also causes referred pain pattern. A tender point is characteristic of fibromyalgia and only causes local pain. Clinical diagnosis of a trigger point is by palpation. It is identified by the local twitch response.4 When firm pressure in a snapping fashion is applied, perpendicular to the muscle fibers over the area of the trigger point, a twitch response is observed.5 This is observed as a transient, but visible contraction or dimpling of the skin and musculature over the area. Recently, attempts have been made to objectively visualize these trigger points using ultrasound.7

Various modalities that have been used to deactivate trigger points include acupuncture, intramuscular stimulation, ultrasonography, manipulative therapy, and injection.4,5 The treatment response is indicated by “local twitch response”. This is supposed to inactivate the trigger points – discrete, focal, hyperirritable spots located in skeletal muscle as a result of primary or secondary response to injury and pain. It has been observed that central sensitization following painful stimuli causes local autonomic and physiologic changes at the trigger point site through neurogenic inflammation. By inactivating, we decrease the inflammatory mediators and neuropeptides such as substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide, etc.6,7 The actual treatment effect resulting from trigger point injection has never been conclusively proven. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that the actual injectate, such as a solution of steroid with or without local anesthetic, does not make much difference.8,9 It is considered that the treatment effect (if any), is due to the process of needling itself. However, in practice it is commonly done as this procedure is quite simple and without significant side effects. Some articles have described such needling in detail.5 A Cochrane review looking at available evidence from the use of acupuncture for neck pain observed better short-term pain relief in the acupuncture group compared with sham acupuncture. However, most studies were low to moderate in quality.10

8.1.2. Pain Education and Behavioral Approaches

Pain education

Therapeutic patient education, an education method and learning experience helping patients gain and retain skills they need to manage their disorder/disease in the best way possible,11 is a tool that clinicians use daily. The educational initiative can be formal or informal to help patients build on knowledge, ensure experiential individualized involvement,12 and establish goals and pedagogy based on the patient’s needs. Evidence suggests that:

- For acute WAD, an education whiplash video2 or whiplash booklet both focusing on simple reassurance advice and activation may be sufficient in the initial management for people with minimal injury along with a trajectory of natural recovery. However, for those with higher pain and disability simple advice may not be sufficient.

- For chronic neck pain including WAD, pain and stress coping skills as well as workplace ergonomics improve function or participation levels but may not change pain; and

- For chronic WAD or neck pain, a cognitive behavioral education approach leads to a small but long-term improvement in function as well as reduced fear avoidance beliefs in the short term. However, once again it may not reduce pain intensity.13

A number of behavioral approaches listed below in conjunction with pain education can be considered and incorporated into standard conventional practice methods by physicians and allied health practitioners for chronic pain management. This approach requires additional special training as well as support. More detailed assessment and management considerations for psychological treatment are considered in Chapter 9.

Behavioral approaches:

- Graded activity;

- Pain neurophysiology education;14-16

- Realistic goal setting:17-21 managed expectations;

- Redirection toward functional goals;

- Encourage self-management: reduce dependence;

- Stress-evaluation techniques, e.g., breathing;

- Mindfulness-based therapy;22

- Cognitive behavioral therapy23,24

- Acceptance commitment therapy25,26

REVIEW 8.1

Which of the following is true regarding trigger point injections?

- Their effectiveness depends upon what is injected

- It works well for neuropathic pain

- Objective presence of trigger points have been demonstrated using microdialysis catheters

- Trigger points are diagnostic of fibromyalgia

Correct answer: 3

8.2 Exercise and Manual Therapy

8.2.1 Exercise

Exercise is foundational and should be used as part of routine practice in the treatment of chronic WAD and neck pain. Both physical and mental benefits underpin the associated mechanisms in the cardiovascular system, immune system, brain function, sleep, mood, and the musculoskeletal system.27 Chronic musculoskeletal pain causes early fatigability, decreases the maximal contraction, and decreases the endurance time involved during submaximal contractions. Endurance strength training is low-load, high-repetition exercise that stress the aerobic pathways, thereby improving oxidative enzyme capacity of slow twitch fibers.28 Stretching lengthens the sarcomeres and reduces the overlap between actin and myosin molecules. This reduces the energy being consumed locally and interrupts the ‘energy crisis’ mechanism. Stretching also improves joint range of motion, leading to decreased pain, increased mobility, and restoration of normal activity.29 Exercise assists to dissociate the emergent fear of movement in chronic pain. Exercise integrated with education on neurophysiology of pain can alter ‘pain memories’. Equal in importance to exercise prescription is exercise adherence30,31 commitment with the stages of change.32 Helping people with neck pain change their behaviors to integrate and maintain exercise into their lifestyle is an important role for all clinicians.

Overarching evidence33,34 to achieve a small to medium clinically important benefit in pain and function over the short to intermediate term for chronic neck pain, in the long term for chronic cervicogenic headache, and to some extent for radiculopathy includes the use of the following elements of exercise: specific strengthening and endurance training of the cervical and scapulothoracic region; stretching/active range of motion when combined with strengthening; and pattern synchronization of muscle recruitment such as neuromuscular eye-neck co-ordination or proprioceptive exercise or feedback techniques using pressure biofeedback. Integrating the cognitive affective elements of exercise (i.e., the mindfulness elements used in Qigong and Tai Chi) into patients’ programs has shown improved pain and function but not quality of life or perceived effect while people are participating with the exercise program but does not have a lasting effect when they stop. Low GRADE evidence supports using sustained natural apophyseal glides (SNAG) exercises for chronic cervicogenic headaches. High GRADE evidence is not yet available for many elements of exercise; thus, there continues to be some uncertainty about the effectiveness of many elements35 of exercise for people with persisting neck pain.20 Low GRADE evidence currently suggests 1) breathing exercises; 2) general cardiovascular fitness training; and 3) stretching alone may not change pain or function at immediate post-treatment to short- term follow-up.

In patients with chronic fibromyalgia, which might be a sequelae of WAD, stretching can be facilitated by by using vapo-coolant or analgesic sprays; and post-isometric relaxation technique (the contract–relax technique) used by physical therapists. Inclusion of very gentle stretch and release techniques or the ‘trigger point pressure release’ technique involving ischemic compression may be used.11

8.2.2 Massage

Massage has been defined as the manipulation of the soft tissues of the body through soft tissue touch and joint manipulation using the hands or a handheld device.36,37 It consists of techniques such as gentle effleurage, pétrissage, and myofascial trigger point release.38 These techniques vary in the manner in which touch is applied, as well as the amount of pressure and intensity that is applied.24 Sherman et al. proposed a three-level classification system for the different massage therapy techniques based on the goals of the treatment, the style, and the technique including relaxation massage, clinical massage, movement re-education, and energy work.37 The biological mechanisms remain unclear; the ‘hands-on effect’ – attention, assessment techniques, other forms of feedback and interaction and communication between the therapist and the patient – may be a “placebo” factor. Nevertheless, proposed beneficial mechanisms may include increased blood and lymph flow, a shift from sympathetic to parasympathetic response, prevention of fibrosis, increased clearance of blood lactate, and effects on the immune system, cognition, and pain including the reduction of pain through increased neural activity at the spinal cord and subcortical nuclei level affecting mood and pain perception through the increase of serotonin and endorphins.39,40

Evidence for massage therapy: as a stand-alone treatment, massage therapy reduces pain and improves function to a small degree compared with no treatment in mechanical neck disorders immediately following treatment. Evidence for the short to long term is lacking. When massage is compared to another active treatment, no clear benefit was evident.40 Because of the limitations of available evidence, no recommendations can be made.41

8.2.3 Spinal Manipulation or Mobilization

Spinal manipulation and mobilization are a form of treatment practiced by physiotherapists, chiropractors, osteopaths, medical doctors, and other healthcare providers to treat musculoskeletal problems. It uses hands to apply specific forces to specific spinal segments and related soft and muscular tissue incorporating the use of instructions and maneuvers to achieve maximal painless range of movement.42

Neuromuscular mobilization techniques may be employed using muscular efforts to mobilize a segment and related tissues. The postulated modes of action include increase in joint movement, changes in joint kinematics, increase in pain threshold, increase in muscle strength, attenuation of alpha motor neuron activity, and enhanced proprioceptive behavior, as well as release of beta-endorphins and substance P.43

Evidence for manipulative and mobilization therapy:44 evidence suggests that it does not matter whether you choose cervical manipulation or mobilization for acute to chronic neck pain; they produce similar effects on both pain and function and may be superior to some simple medications in the long term. For chronic cervicogenic headache, cervical manipulation may be superior to massage or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation to improve pain and function at up to six months’ follow-up. Cervical and thoracic manipulation may be beneficial as a stand-alone treatment; however, mobilization alone may not be.

Exercise plus manipulation or mobilization:45 when added as an adjunct to exercise, manipulation and/or mobilization are beneficial for pain relief, reduced disability and perceived effect for chronic cervicogenic headache, and chronic neck pain with or without radicular findings when contrasted against no treatment in the long term. The benefit is substantive; that is, one needs to treat one in two to five people to achieve up to a 69% treatment advantage. Manipulation or mobilization when added as an adjunct to exercise demonstrates better short-term pain relief (up to three months) than exercise alone, but this advantage disappears in the long term in terms of pain, function, global perceived effect, and quality of life outcomes for neck pain of mixed duration or chronic neck pain with or without headache. Similarly, this combination of care improves pain and quality of life more than traditional care for acute WAD but offers no added benefit for change in function, global perceived effect, or quality of life.

8.3 Other Modalities of Treatment

8.3.1 Ultrasound and Electrotherapies

Ultrasound is a modality that uses piezoelectric crystals to convert electrical energy to mechanical oscillation energy.46 The proposed mechanisms of action of ultrasound for pain relief are increases in local metabolism, circulation, regeneration, and extensibility of myofascial tissue through its thermal and mechanical effects.47 Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, electrical muscle stimulation, frequency-modulated neural stimulation, and electrical twitch-obtaining intramuscular stimulation can all be referred to as electrotherapies.46 Small-sized studies show that ultrasound appears to have a role in providing short-term and intermediate-term improvement in pain and function and can be especially useful as an adjunctive therapy in the treatment of myofascial pain.46-48

8.3.2 Local Laser Therapy

For the most part, we do not fully understand how laser therapy works. Proposed explanations include the “gate theory” and stimulation of the microcirculatory system.45 Limited and small-size studies support the use of specific dosages of laser therapy for neck pain. Overall, the evidence is unclear.49

8.4 References

- Seferiadis A, Rosenfeld M, Gunnarsson R. A review of treatment interventions in whiplash-associated disorders. Eur Spine J 2004;13:387-97.

- Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prepared by the International Association for the Study of Pain, Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain Suppl 1986;3:S1-226.

- Travell JG, Simons DG. Travell & Simons’ Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, 2nd edn. Baltimore, Maryland, USA: Williams and Wilkins; 1999.

- Alvarez DJ, Rockwell PG. Trigger points: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 2002;65:653-60.

- Lavelle ED, Lavelle W, Smith HS. Myofascial trigger points. Med Clin North Am 2007;91:229-39.

- Shah JP, Danoff JV, Desai MJ, et al. Biochemicals associated with pain and inflammation are elevated in sites near to and remote from active myofascial trigger points. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89:16-23.

- Sikdar S, Shah JP, Gebreab T, et al. Novel applications of ultrasound technology to visualize and characterize myofascial trigger points and surrounding soft tissue. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009;90:1829-38.

- Cummings TM, White AR. Needling therapies in the management of myofascial trigger point pain: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001;82:986-92.

- Tough EA, White AR, Cummings TM, Richards SH, Campbell JL. Acupuncture and dry needling in the management of myofascial trigger point pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Pain 2009;13:3-10.

- Seo SY, Lee KB, Shin JS, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture and electroacupuncture for chronic neck pain: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Chin Med. 2017;45:1573-95.

- WHO. Therapeutic Patient Education, Continuing Education Programmes for Health Care Providers in the Field of Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 1998.

- Knowles MS. The modern practice of adult education: Andragogy versus pedagogy. New York: Associate Press; 1970.

- Gross A, Forget M, St George K, et al. Patient education for neck pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Mar 14;(3):CD005106.

- Louw A, Diener I, Butler DS, Puentedura EJ. The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:2041-56.

- van Oosterwijck J, Nijs J, Meeus M, et al. Pain neurophysiology education improves cognitions, pain thresholds, and movement performance in people with chronic whiplash: a pilot study. J Rehabil Res Dev 2011;48:43-58.

- Meeus M, Nijs J, van Oosterwijck J, van Alsenoy V, Truijen S. Pain physiology education improves pain beliefs in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome compared with pacing and self-management education: a doubleblind randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010;91:1153-9.

- Busch AJ, Schachter CL, Overend TJ, Peloso PM, Barber KR. Exercise for fibromyalgia: A systematic review. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1130-44.

- van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Kuijpers T, et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of physical and rehabilitation interventions for chronic non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J 2011;20:19-39.

- Searle A, Spink M, Ho A, Chuter V. Exercise interventions for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Rehabil 2015;29:1155-67.

- Louw S, Makwela S, Manas L, Meyer L, Terblanche D, Brink Y. Effectiveness of exercise in office workers with neck pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. S Afr J Physiother. 2017;73:392.

- Miyamoto GC, Lin CC, Cabral CMN, van Dongen JM, van Tulder MW. Cost-effectiveness of exercise therapy in the treatment of non-specific neck pain and low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:172-81.

- Chiesa A, Calati R, Serretti A. Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clin Psychol Rev 2011;31:449-64.

- Williams AC, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11:CD007407.

- Eccleston C, Morley SJ, Williams AC. Psychological approaches to chronic pain management: evidence and challenges. Br J Anaesth 2013;111:59-63.

- McCracken LM, Vowles KE, Eccleston C. Acceptance-based treatment for persons with complex, long standing chronic pain: a preliminary analysis of treatment outcome in comparison to a waiting phase. Behav Res Ther 2005;43:1335-46.

- Wicksell RK, Ahlqvist J, Bring A, Melin L, Olsson GL. Can exposure and acceptance strategies improve functioning and life satisfaction in people with chronic pain and whiplash-associated disorders (WAD)? A randomized controlled trial. Cog Behav Ther 2008;37:169-82.

- Abernethy B, Kippers V, Hanrahan SJ, Paddy MG, McManus AM, MacKinnon L. Biophysical Foundations of Human Movement. 3rd edition. Champaign: Sheridan Books, 2013. 3rd edition, Sheridan Books; 2013.

- Borisut S, Vongsirinavarat M, Vachalathiti R, Sakulsriprasert P. Effects of strength and endurance training of superficial and deep neck muscles on muscle activities and pain levels of females with chronic neck pain. J Phys Ther Sci. 2013;25(9):1157-62.

- Page P. Current concepts in muscle stretching for exercise and rehabilitation. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012;7(1):109-19.

- Crandall S, Howlett S, Keysor JJ. Exercise adherence interventions for adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Phys Ther. 2013;93(1):17-21.

- Jordan JL, Holden MA, Mason EE, Foster NE. Interventions to improve adherence to exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2010(1):CD005956.

- Zimmerman GL, Olsen CG, Bosworth MF. A ‘stages of change’ approach to helping patients change behavior. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(5): 1409-16.

- Kay TM, Gross A, Goldsmith CH, Rutherford S, Voth S, Hoving JL, et al. Exercises for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;8:CD004250.

- Blanpied PR, Gross AR, Elliott JM, et al. Neck pain: revision 2017. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47:A1-A83.

- Sahrmann SA. Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. St. Louis: Mosby Inc., 2002.

- Brosseau L, Wells GA, Tugwell P, et al. Ottawa Panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on therapeutic massage for neck pain. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2012;16:300-25.

- Sherman KJ, Dixon MW, Thompson D, Cherkin DC. Development of a taxonomy to describe massage treatments for musculoskeletal pain. BMC Complement Altern Med 2006;6:24.

- Kutner JS, Smith MC, Corbin L, et al. Massage therapy versus simple touch to improve pain and mood in patients with advanced cancer: a randomized trial. Ann Int Med 2008;149:369-79.

- Sagar SM, Dryden T, Myers C. Research on therapeutic massage for cancer patients: potential biologic mechanisms. J Soc Integr Oncol 2007;5:155-62.

- Moyer CA, Rounds J, Hannum JW. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychol Bull 2004;130:3-18.

- Patel KC, Gross A, Graham N, et al. Massage for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD004871.

- Ernst E, Canter PH. A systematic review of systematic reviews of spinal manipulation. J R Soc Med 2006;99:192-6.

- Meeker WC, Haldeman S. Chiropractic: a profession at the crossroads of mainstream and alternative medicine. Ann Int Med 2002;136:216-27.

- Gross A, Langevin P, Burnie SJ, et al. Manipulation and mobilisation for neck pain contrasted against an inactive control or another active treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;9:CD004249.

- Gross AR, Paquin JP, Dupont G, et al. Exercises for mechanical neck disorders: A Cochrane review update. Man Ther 2016;24:25-45.

- Annaswamy TM, De Luigi AJ, O’Neill BJ, Keole N, Berbrayer D. Emerging concepts in the treatment of myofascial pain: a review of medications, modalities, and needle-based Interventions. PM R 2011;3:940-61.

- Ilter L, Dilek B, Batmaz I, et al. Efficacy of pulsed and continuous therapeutic ultrasound in myofascial pain syndrome: a randomized controlled study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2015;94:547-54.

- Manca A, Limonta E, Pilurzi G, et al. Ultrasound and laser as stand-alone therapies for myofascial trigger points: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Physiother Res Int 2014;19:166-75.

- Gross AR, Dziengo S, Boers O, et al. Low level laser therapy (LLLT) for neck pain: a systematic review and meta-regression. Open Orthop J 2013;7:396-419.