2 The Story of Two Whiplash Victims

2.1 The Scene of the Accident

Amanda and Claudia are friends; they were excited as they headed for Claudia’s home for a party. Amanda, who was driving the car, got distracted by Claudia’s conversation and suddenly realized that she had to stop for a red light at an intersection. She immediately applied the brakes and was hit by a truck from behind; it rammed into the back of their vehicle throwing both of them forward in their seats. At the scene, an ambulance was called. Both Claudia and Amanda were conscious, but dazed. During the accident, Amanda had her head turned to the right to converse with Claudia. The impact forced her head back into extension and exaggerated the rotation before it came into violent contact with the headrest. The headrest was set too low relative to her head allowing for even greater extension of the neck. Amanda’s head was then thrown forwards into flexion and rotation to the left.

Headrest Use and Whiplash Injuries

In the 1960s, it was observed that head restraints in car seats reduce neck motion, and therefore would limit whiplash injuries.1 Hence, since December 1968, all passenger cars manufactured in the USA are required by law to have the head rest extending a minimum of 700 mm (27.5 inches) above the hip level. Two important aspects of head restraints are their height and their distance from the back of the head. Since 2001, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety rated the passenger cars manufactured in the USA, based on the head restraint configuration, as follows: good, acceptable, marginal, or poor. More favorable ratings are given if the head restraints measure higher and closer to the head of an average size male. Recent changes by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration–USA require that head restraints achieve a minimum height of 750 mm above the hip in its lowest position, and 800 mm when adjusted to its highest position.2 Along with these parameters the restraint must not be more than 50 mm away from the typical position of an occupant’s head. The Canadian guidelines are highlighted in the following websites of traffic safety:

- Canada Safety Council. Properly Adjusted Headrests Prevent Injuries: https://canadasafetycouncil.org/trafficsafety/properly-adjusted-headrests-prevent-injuries

- Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety: https://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/ergonomics/driving.html

Several car manufacturing companies have also introduced newer designs with their own unique attributes to safety: Toyota, Whiplash Injury Lessening System (WILS); Volvo, Whiplash Injury Prevention System (WHIPS); and Saab, Saab Active Head Restraint (SAHR).

REVIEW 2.1

Which of the following is true?

- All patients of neck injury need a CT scan

- The height and placement of the headrest plays an important role in preventing injury to neck structures

- Presence of localized pain over the shoulder can be considered a red flag during examination of a neck injury patient

Correct answer: 2

2.2 Amanda in the ER

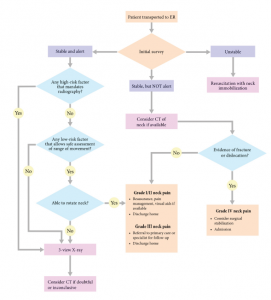

Emergency Room Algorithm of Management for Acute Injuries Involving the C-spine

Within a short time, Amanda became aware of the intense pain in the left side of her neck. A shooting electric shock-like pain ran into her left shoulder and along the lateral aspect of the left arm onto the top of her thumb. It was accompanied by significant neck pain and tremendous stiffness when she tried to move. Her left shoulder began to ache intensely, and she noticed a headache involving the back of her head on the left-hand side. The electric shock-like pain in her left arm soon settled down into a sensation of pins and needles accompanied by a numb, heavy sensation. She felt unable to get out of the car due to the pain; she was quite shaken by the whole incident. She was placed in a hard collar by the paramedics and taken to the nearest emergency department where she was evaluated by the trauma team. The emergency room algorithm of management for acute injuries is described in Figure 2-1.

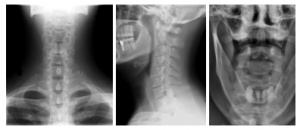

A primary survey was completed and significant injuries were ruled out. However, the secondary survey resulted in some concern regarding the amount of neck pain and guarding, the complaints of numbness and weakness in the patient’s left arm, and the observed biceps and brachioradialis reflex changes (C5-C6). Plain films and a CT scan of the cervical spine were therefore ordered. A 3-view X-ray was performed to rule out C-spine injuries (Figure 2-2). The criteria for imaging are noted in the Canadian C-spine rule (Figure 2-3).3 Both X-rays and CT scan revealed no fractures and preserved alignment. She was then diagnosed as WAD grade III.

2.3 Assessment of Those with Whiplash and Neck Pain

The Canadian C-spine rule is used in patients with trauma3 (Figure 2.3), and the following questions and triage algorithm should be considered in a new patient with neck pain. When considering the history, determine whether there are any red flags. Red flags are clinical features that indicate an increased risk of specific conditions that can present with neck pain and require urgent attention. Red flags may include:

- Category I: factors that require urgent attention include blood in sputum; loss of consciousness; neurological deficits crossing three myotomal levels; perianal numbness; progressive neurological deficit; pulsating abdominal mass.

- Category II: factors that require subjective questioning and precaution include age >50 years; clonus; fever; gait deficit; disorder with predilection of infection or hemorrhage; history of cancer; or cortisone use.

- Category III: factors that require further physical testing and differentiation including abnormal reflex; bilateral radiculopathy; unexplained referred pain; unexplained weakness across upper or lower limb. Based on these questions the patient is triaged and classified into WAD grade III. The WAD grades are detailed in Chapter 1.

2.4 Amanda’s Discharge from ER & Visit to the Fracture Clinic

Amanda was discharged from the emergency room with an appointment for an outpatient magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck and referral to the spine service through the fracture clinic the following week. She was given a prescription for a moderate-strength opioid, along with non-steroidal anti-

inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), and instructed to use a soft collar for short-term stabilization until her fracture clinic appointment.

By the time she was seen in the fracture clinic her left arm felt much better, although she continued to have significant achiness in the shoulder. The MRI demonstrated a small posterolateral disc protrusion at C5-C6 and some edema at the left C6 nerve root, but nothing of additional note.

Amanda was also concerned about the ongoing stiffness and pain. She was told that she had sustained a ‘soft tissue’ whiplash injury apart from the disc protrusion. A discectomy would only be required should the disc protrusion progress to the point of nerve root compression resulting in neurological compromise. She was advised to stay active, participate in regular activity as tolerated, and was prescribed physiotherapy with routine analgesics including NSAIDs and tricyclic antidepressants to help her pain and sleep.

2.5 References

- Severy DM, Brink HM, Baird JD. Backrest and Head Restraint Design for Rear-End Collision Protection, SAE Technical Paper Series 680079, Society of Automotive Engineers, Warrendale, PA, 1968.

- Farmer CM, Wells JK, Lund AK. Effects of head restraint and seat redesign on neck injury risk in rear-end crashes. Traffic Inj Prev 2003;4:83-90.

- Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen KL, et al. The Canadian C-spine Rule for radiography in alert and stable trauma patients. JAMA 2001;286:1841-8.