4.1 The Learning Curriculum

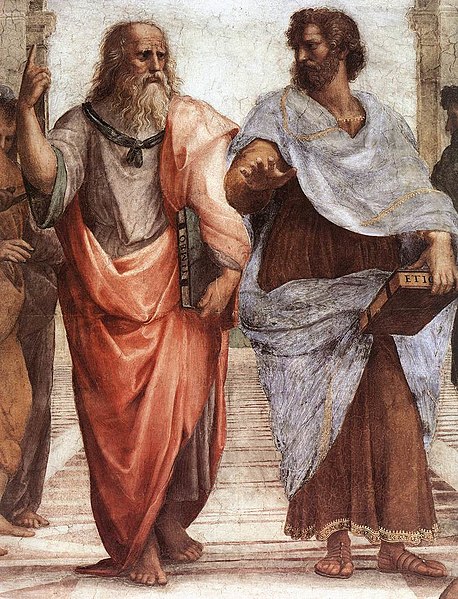

What does it mean to be authentic? Similar words related to authentic or authenticity are: genuine, original, veritable, and rightful. One might say to be authentic means to be genuine or rightful in a context. What does this mean for authentic education? As previously discussed, authentic education, or authentic learning, allows learners to traverse and meaningfully discuss concepts and relationships connected to the world around them at an individualized pace with an interdisciplinary approach. Could it be said that authentic education is a return back to genuine and original learning? This could be the case, as Lodge suggests, that learning through action in an authentic practice has long been enacted in workplaces, even tracing as far back as Plato in The Academy[2].

Authentic education provides an emphasis on action and experience which is of growing interest to students given their keenness and enthusiasm to garner workplace learning for job preparedness, especially in colleges and universities. The learning curriculum in a modern educational framework strives to achieve this authentic action as a return to true learning. Marsh and Willis identify currere, or the autobiographical reflection on educational experiences[3], as an actionable approach for the learning curriculum.

How does this relate to the model of workplace learning? Stephen Billett asserts that the focus of a curriculum towards workplace learning and guided participation in learning every day should be paramount within a workplace curriculum model[4]. There are a couple of ways to combine authentic education with a workplace-learning curriculum. First, start with the pedagogical structure from previous chapters, such as organizing physical spaces and creating authentic activities for learners to be integrated into these models. Second, use authentic assessments, which are tailored accomplishments that are significant and relatable to the learning curriculum. This assessment goes beyond multiple-choice tests and focuses on development through a logistical and pragmatic structure.

It is Lauren Resnick who, as president of the American Educational Research Association in 1987, outlined the process of learning inside and outside of schools. She described the relationship between schooling and economic participation this way:

“Ever since the Smith-Hughes Act of 1917, schools have been expected to provide certain students with experience with the same kinds of machines and the same kinds of tasks that they will encounter in the workplace.”[5] (p. 16).

In addition, these are her comments on skills for authentic learning outside of schools:

“Beyond reorganized job-specific training, modern economic conditions also call for education aimed at helping people develop skills for learning even when optimal instruction is not available.”[5] (p. 17).

Ultimately, it is through this concept of authentic action within curricula that will help students achieve goals to be successful in their endeavours once they leave school and enter the workforce, be it through a coaching model of pedagogy or an apprenticeship model. The learning curriculum needs to provide actionable teaching and resources to meet the needs of students entering the workforce. Test your knowledge by selecting all the characteristics of authentic assessment in the activity below.