2.1 The Education System in North America

In order to understand the educational system in North America, it helps to know its history. With the growth of industrialization in nineteenth-century America, new cities started forming around the areas outside of the Atlantic North East. Cities such as Kansas City, Detroit, St. Louis, Cleveland, and Chicago were all growing. Higgs cites that Kansas City and St. Louis saw spectacular growth due to the rise of urbanization for industrialized work[1]. According to Lyons, Chicago saw exponential industrialized growth making it the second-largest city in the country next to New York. With that, came more families with more children. Given that most men worked in factories, and anti-child labour laws were passed along with compulsory education laws, Chicago became one of the first cities to enhance public education, given the massive influx of people[2]. Then, the concept of a child’s education as a cornerstone of growth came into play. With this came the creation of educational laws. This could be seen as a reactionary method born out of labour and human rights’ laws related to getting children out of the harmful conditions of factory work.

Although the children were now removed from the workplace, this environment still had an impact on the educational system. Management education or industrialized education became commonplace in public schools, forming from the managerial systems in England and in Germany[3]. This became a common theme within schools, similar to how contemporary students experienced schools during recent times in public education. Rows of seats focused on the front of a classroom, bells signifying when to change stations and have a lunch break; all of these methods were born from the industrialized model of education.

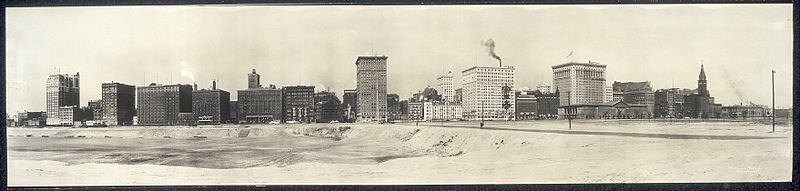

A photograph, which has never been previously made available to the public (e.g. by publication or display at an exhibition) and which was taken more than 70 years ago (before 1 January 1950).

Even after laws and regulations, the concept of public education was that schooling was preparing students to enter back into the factory, given the cognitive training of the public-school system during these years. However, looking at this critically, an argument can be made about productivity in schooling in this period, such as the need and demand for educators. According to Blinder, the growth of education and learning was massive, given the growth of the industry, regarding the United States educational system as one of the best in the world at the time[4]. This would lead to the growth of the higher-educational system within the United States, such as the land-grant universities promoting vocational research initiatives.

The key argument with the public-educational system is that the theory around education could have an industrial precedent, but in the end, the individuals in the classroom are not widgets; they are humans and need to be treated as such. John Dewey and his work of Democracy and Education provide answers to the human side of education, especially in the early twentieth century. Dewey outlined the democratic conception of education, bringing in the human aspect towards learning and the entanglement between humanism and learning:

“Society is conceived as one by its very nature. The qualities which accompany this unity, praiseworthy community of purpose and welfare, loyal to public ends, mutuality of sympathy, are empathized…Any education given by a group tends to socialize its members but the quality and value of the socialization depends on the habits and aims of the group.”[5]

Gordon and English analyze Dewey’s work through the perspective of challenging neoliberal globalization. They find contention with Dewey’s pragmatic work of being difficult to comprehend, considering that Dewey offered an unclear framework. However, the authors also find positives in Dewey’s approach to connect societies and promote new ways of learning and education[6]. The authors take a neo-Marxist stance to Dewey’s understanding of democracy with regard to the nature of a capitalist economic system of educational theory. However, it can be said that democracy in relation to freedom of thinking presupposes the ability to think and pursue any form of education outside of an industrialized or collective nature, whatever may fit for the individual. In turn, this supports a classical liberal approach as the individual guiding her or his education in a way that is deemed fit outside of an economic understanding of capitalism or Marxism. The logical and pragmatic design of Dewey transcends theoretical structures of economics and can be beneficial to reforming education in our current state, using the past as a lever. Click on the information tabs below to learn more about the industrialization of learning in North America during the twentieth century.