20 Talks

Read time: 8 minutes

Overview

This chapter will provide guidance and tips on giving a talk at a conference, seminar, research update, or thesis defence.

Sections in this chapter

- Format and length

- Slides

- Planning your talk

- Tell a story

- Preparing your talk

- Accessibility

- Make it interactive

- Common mistakes

Format and Length

Oral presentations for science communication have many possible formats:

- Conference presentations (15 minutes, 45 minutes)

- Seminars (45-50 minutes)

- Thesis defence (10-20 minutes, or 45-50 minutes)

- Research updates

- Tutorials and Lectures

Most oral presentations at conferences or in a thesis defence are 10-20 minutes in length, whereas invited talks, lectures, or seminars can be longer. The oral presentation should be designed to fit the time period but must allow for the introduction of the speaker, questions at the end of the talk, and technical glitches. In a one-hour time slot, a talk should be 45-50 minutes to allow time for questions and introduction.

A rough guide to the number of slides needed is:

- for a simple slide – one per minute

- for a complex slide – one per two minutes

- calculate where the midpoint of your talk is, to use for reference

Slides

Talks are usually accompanied by visual media, like a PowerPoint slide deck, or in some cases a blackboard/whiteboard (this is considered “old school”). Most universities have PowerPoint and KeyNote templates that you can download and use for research presentations (Click here for Queen’s University Templates).

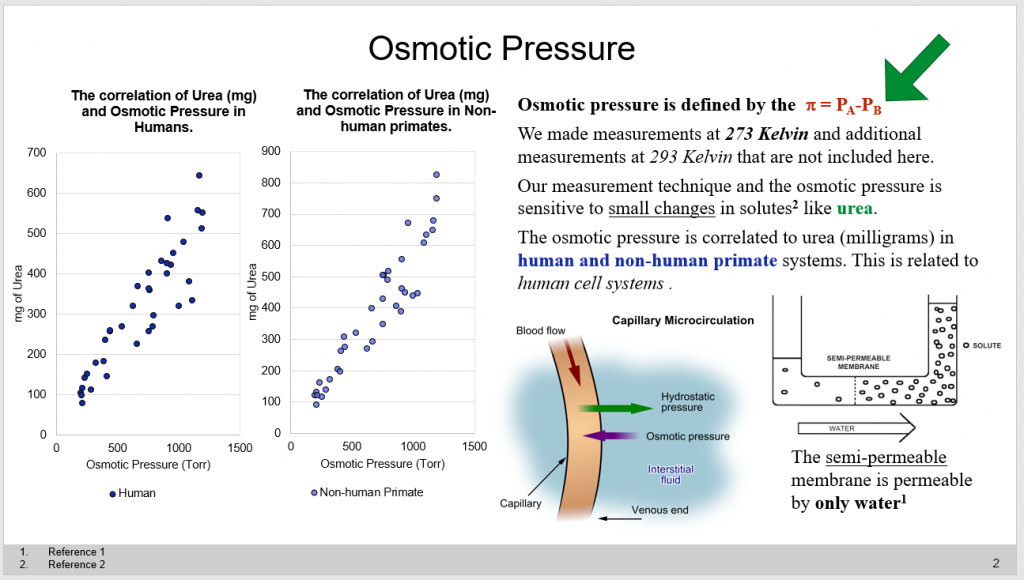

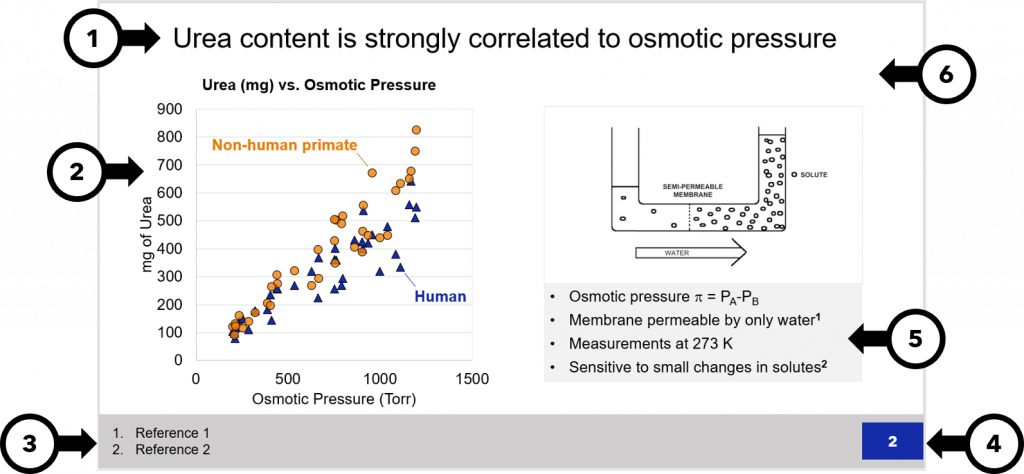

Here are several tips for designing slides (see Figure 20.1):

- Write a descriptive title that contains the key message

- Keep text size at 18pt or above, including in graph axes

- Keep a space for references cited in the slide

- Have a large and clear slide number

- Limit text and use bullet points, not paragraphs

- Use plenty of white space to avoid over-crowding

Planning your talk

Before you start making slides or thinking of what you want to say, take some time to consider the big picture and plan your talk. As always, consider first who your audience will be: What is their experience or expertise? What will they be interested in? What is their language level? Once you have a clear idea of your intended audience, decide what message you have for them, what you want them to take from your talk. Have a central message that is reflected in your talk’s title.

In science, talks can be a venue to showcase your work and effort, and presenters can sometimes get overly ambitious or want to impress the audience (e.g., a thesis defence or interview talk). This mentality can lead to over-loaded talks that try and present too much data, or too many different research projects. In your talk, stick to ONE STORY. This story might be a single research project or a single component of the project. This doesn’t mean you can’t mention other projects or the broader context of your work, but only that you must stick to your one story for the bulk of the talk.

Tell a story

Since our framework for giving a talk is to tell a story, what makes a good story? Some things we’ve already discussed, including having a clear central message. The second is to embrace conflict. In research, this means describing mistakes or debate that stemmed from your research; often, failure leads to a new discovery, which creates a compelling story.

Shohini Ghose, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Canada.

Once you have your story idea, there are many ways to order a talk — sequential, categorical, problem-solution, etc — all involve an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. The introduction is crucial in getting your audience to the same level of background and getting them excited about research. So why is it that the audience often starts to lose interest in the introduction?

Introduction

Too many presenters start their talk, their story, by diving into the details. They will explain everything that has been done before their work and define the area of research and its terms. These are important points for the talk, but the issue is that the audience does not know why you are telling them all this information. Even if the audience is interested in the topic, they will disengage if the motivation for the research being presented in the talk is unclear.

The solution to a boring introduction is to start with a hook (Table 20.1). This can be a compelling message related to the research question, e.g., “Is there a mosquito strategy that could eliminate dengue virus?”.[1] Such a question is engaging even to an audience with no prior knowledge because it makes them want to learn more, which leads perfectly into an explanation of what is the dengue virus, why do we want to eliminate it, and what are mosquito strategies? Another way to hook the audience in the introduction is to tease an exciting or surprising result, then explain how it was reached. This is similar to a movie where you see where the characters end up, and then the movie explains how they got there. This approach is excellent for an expert audience, who will understand the importance of the result and want to know all the details that follow.

Table 20.1. How to structure an engaging introduction to your talk

| Introduction | Boring | Engaging |

| 1 | “Lanthanide perovskites are..” | Hook: “Can molecular design help solve global challenges?” |

| 2 | “MOFs are…” | “We are trying to make new MOFs to capture carbon pollution” |

| 3 | “These compounds are made using…” | “MOFs are…” “Lanthanide perovskites are..” |

| 4 | “We are trying to make new MOFs to capture carbon pollution” | “These compounds are made using…” |

Body

This is the bulk of your talk, where you explain your methods, results, and discuss the findings, and it can easily get out of hand if you have lots of data. Keep your keep message clear, and cut out any content that does not support this message. Remember that you can always discuss related content after your talk when the audience asks questions. If you are preparing a slide deck, use this trick: each slide should have a single “key message” that related to the overall goal of the talk. Then, organize the slides so that they flow along with your intended story.

Conclusion

To conclude your talk, bring the audience back to the “big picture” and reiterate your overall message. Bring the focus from the past (what was done) into the present and future. Describe the impact of your work, the significance, and what questions remain. For the final slide, make sure to acknowledge your colleagues, collaborators, and those who funded the research. Tell the audience how they can learn more by contacting you or how to find the relevant publications.

Preparing your talk

When preparing your talk, start to develop an outline or storyboard. Create rough versions of your visual aids (slides) and key points on single sheets of papers or on individual PowerPoint slides (Table 20.2). In this process, it can help to try and tell your story out loud. Talk through these ideas with yourself or a colleague, this will give you the opportunity to rearrange the sequence, adjust wording, etc. Use the “Slide Sorter” view in PowerPoint to look at your overall outline and rearrange your story.

Martha Davis provides excellent advice for planning and making visual aids for a talk in her book chapter “Visual Aids to Communication”.[2] She suggests being as consistent as possible with how you use colour, symbols, axes, etc. Don’t bother numbering your figures, and avoid tables or large paragraphs of text, and make visually appealing figures following the guidance from the chapters in Module 2: Visuals.

Avoid using too many devices for emphasis: the use of too many colours, italics, bold print, or underlining. If these enhancements are overused they will detract attention from the key message of the slide. Instead, use your voice for emphasis.

Table 20.2. Outline for a 15-minute talk with slides (adapted from Davis, 2005)

| Slide | What to include | # of slides |

| Title | Title and subtitle, author, affiliation, date. | 1 slide |

| Forecast | The ‘hook’. Describe the nature of the problem, the big research question, and the clear central message. | 1 slide |

| Outline | Optional. Sets out the structure of the talk. | 1 slide |

| Background | Motivations, definitions, related work, and methods (briefly). | 3-4 slides |

| Results | Key findings and insights (focus on 1-2 rather than all). Avoid using text and tables. Interpret the results as you go. | 5-6 slides |

| Summary | Bring the audience back to the big picture, leave them wanting to read more. | 1 slide |

| Future work | Optional. Describe what you plan to do next. | 1 slide |

| Acknowledgements | Thank your colleagues, collaborators, and funding | 1 slide |

| Back-up slides | Optional. Keep some extra slides that you didn’t have time to cover, but that might be useful for discussion. | 0-3 slides |

| Total | ~15 slides |

Accessibility

- Although this chapter advised you to limit the text on your slides, you should avoid eliminating text entirely. Text on slides is important for the hearing impaired, just like having close captions in a video.

- It’s also important to always use a microphone if it is offered! Don’t say “No, I don’t need it, I speak loudly”. You don’t know how well your voice carries in that room, and are likely being offered a microphone for a reason.

- Microphones are sometimes linked to devices like hearing aids that can help those with hearing impairments.

- Make sure your slides follow the best practices for visual accessibility. Check that your colours are distinguishable for the colour-blind.

- Don’t overcrowd your slides. Some disabilities make it difficult to look at screens for too long or to take in too much information at once.

Make it interactive

Educational research has proven how activities in the classroom can improve learning outcomes and student engagement. This idea can also be applied to research talks to help bring in our audience and keep them listening throughout your presentation (Table 20.3). Make your presentation interactive by having audience members answer questions either out loud or in their mind, or create time for audience members to discuss something in the middle of your talk. It can be intimidating to give away control of your presentation, but the reward is an engaged audience who feels like they are participating, rather than just listening.

Table 20.3. Strategies to make your talk interactive

| Activity | Description | Example |

| Ask a question verbally | The question can be something for the audience to silently think about, or make it clear if you expect an answer or raised hands. | “And what do you think happened next?” “Does anyone know who first discovered this reaction?” |

| Ask a question using polling software | There are some great, easy, and free ways poll your audience from their devices, like Poll Everywhere or Mentimeter |  |

| Think-pair-share | Pose a question, then give your audience a minute to discuss with each other. Ask audience members to share afterwards. | “Why do we need to use this method? Discuss with your neighbour for a minute, then I want to hear what you all think.” |

| Demonstration | Ask your audience to do something that helps demonstrate the point you are trying to make. | “It is hard to remember a phone number if I disrupt your memory with lots of other numbers. Remember this number on the screen, you will need to recall it at the end of the talk” |

Below is a slide containing some common mistakes people make when creating presentation slides. Can you find them all?

Click here to show an answer

- The slide is over-crowded, there not enough white space

- The title is not descriptive

- Text is too small in the figures and references

- Data points in the figures are small and difficult to distinguish

- Instead of a legend, data could be labelled on the graph

- The two graphs could be combined into one

- Too much text, written in sentences/paragraphs rather than bullets

- Enhancements (bold, underline, italics, colour) are overused

- Red and green may not be accessible to colour-blind audience members

- The slide contains some irrelevant information (“measurements at 293 K are not included here”)

- The slide number is small and might get cut off when projected