3 Style Tips

Read time: 4 minutes

Overview

This chapter will discuss tips for improving the style and readability of your scientific writing. Style is the way your research is described, whereas format it the way your paper is arranged.

Sections in this chapter

- Balancing honesty and efficiency

- Precision

- Clarity

- Familiarity

- Fluidity

- Forthrightness

- Conciseness

- Imagery

Balancing honesty and efficiency

Scientific writing is a craft rather than a science, and is subject to two constraints: Honesty and Efficiency

Honesty – you must include all research results, including the data points, even those which don’t fit the curve. You must give fair treatment to opposing theories and experiments.

Efficiency – you must inform your audience as efficiently as possible, however not with the paper with the shortest length, but with the paper that takes the readers the shortest time to understand.

What makes for good science writing?

- Have something to say

- Be logical and clear

- Brevity

- Apply simple rules of style

- Read other’s writing

- Try talking (out loud) before writing

- Know and respect your audience

- Revise and proofread

- Learn to cut out words

- Get help from peers

Precision

Choose and use the right words in your scientific writing. For example, know if you need to use “weight” or “mass”. Don’t hesitate to repeat a word if the word is the right word. Ideally a scientific term should only have one meaning, but there are many words that have different common meanings than scientific meanings. For instance, a “theory” in common language is like a hunch or guess, whereas in science theories are built from large bodies of evidence. Be aware of multiple meanings or negative connotations in your writing (e.g., “adequate” can have a negative connotation).

Clarity

Keep your sentences as simple as possible in scientific writing. Follow the guidelines in the Writing Basics chapter to make your sentences short and clear.

Using jargon or pretentious words and phrases will reduce the clarity if your writing. You may be encouraged to use these words by your supervisor or peers, and you will see them everywhere — they look smart, right? — but they are part of what makes science so difficult to read. Table 3.1. shows a list of words and phrases you should stop using along with simple replacements. See the next section on Familiarity to learn more about jargon.

Table 3.1. Pretentious words and phrases to avoid

| Pretentious words and phrases | Simple replacements |

| approximately | about |

| affords / furnishes | gives |

| novel | new |

| implement | carry out |

| utilize | use |

| activate | start |

| facilitate | make |

| subsequently | then |

| “…clearly demonstrates…” | “…demonstrates…” |

| “As is well known, amines…” | “Amines…” |

| “Obviously, the reaction…” | “The reaction…” |

Familiarity

Find and use language that is familiar to your audience (this requires knowing the audience for your writing!). If you need to use an unfamiliar word, define it using words in which are familiar. You can also use use examples or analogies to help the reader.

It can be hard to avoid jargon, especially phrases that developed in your own laboratory and that you use with your peers. Some examples of common jargon phrases are:

- “the solvent was rotovapped”

- “the compound crashed out of solution”

- “the NMR showed”

Fluidity

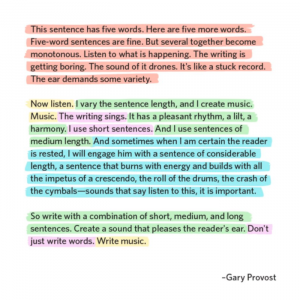

Fluid writing is difficult to accomplish in the first draft, and we’ll come back to it when we discuss Editing your work. One factor to fluidity is variability (see “Write music” below); vary your sentence or paragraph length and structure. The second factor is to use strong connective words, or conjunctions, to keep your thoughts flowing from one to the next.

Write music

This tip comes from “100 ways to improve your writing “ by Gary Provost.

Forthrightness

Use active-voice whenever possible to avoid vagueness that often comes with passive-voice. Use strong nouns that require few adjectives, and use strong active verbs and don’t overly hedge your statements (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2. Weak and passive vs. strong and active phrases

| weak verb phrase: strong verb: |

“made the measurement of” “measured” |

| needlessly passive: active: |

“is used to detect” “detects” |

| needlessly passive: active: |

“is capable of” “can” |

Conciseness

Being concise means eliminating redundancies. This is difficult to do while writing, but can be easier during the revision stage. Below are some examples of common phrases, with the redundant word in [square brackets]. If you imagine a sentence for each one with and without the redundant word, the meaning should remain the same.

Redundant words

- [already] existing

- [completely] eliminate

- [basic] fundamentals

- [currently] underway

- [continue to] remain

- mix [together]

- never [before]

- [still] persists

Replace these phrases with single words:

- “in the light of the fact” = because

- “in the vicinity of” = near

- “at this point in time” = now

- “has the ability to” = can

Examples of redundant wording

Example 1

WORDY: US Government blackout order during World War II:

“Such preparations shall be made as will completely obscure all Federal buildings and non-Federal buildings occupied by the Federal government during an air raid for any period of time from visibility by reason of internal or external illumination.”

CONCISE: President Roosevelt’s response:

“Tell them that in the buildings where they have to keep the work going to put something across the windows.”

Example 2

WORDY: Our website has made available many of the things you can use for making a decision on the best solvent. (20 words)

CONCISE: Our website presents criteria for choosing the best solvent. (9 words)

Imagery

Often in writing, we are trying to supply a mental image of our science and research. Chemists work at the molecular scale, on processes not visible even under most microscopes, and imagistic words can help convey this molecular world, for example…

“the host molecule encapsulates the guest”

Using a description that evokes the five senses can also help a scientist trying to reproduce a method, e.g.,

“a red syrupy oil” or “bright yellow needle-like crystals”.

When words are not enough, we can use schemes, figures, and other illustrations to convey our meaning in science: you’ll see more on that in Module 2.