9 Challenges to Educational Practice

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to

- Define global education.

- Explain if and how global education is being realized at the secondary and post-secondary levels of education in Canada.

- Explain how the global economic crisis is related to education-related matters in Canada and around the world.

- Define neoliberalism.

- Identify the ways in which neoliberalism has influenced education at both the K–12 and post-secondary levels.

- Explain what is meant by globalization and internationalization and how the two terms are different.

- Explain the various strategies post-secondary institutions are using to internationalize their campuses.

- Identify the four models used by different countries to fund tertiary education.

- Describe current perceived challenges in the instruction of post-secondary students.

Introduction

The previous chapters have laid the foundation for understanding the sociology of education within a mostly Canadian context. Increasingly, however, forces of globalization are creating networks of interconnectedness between people, businesses, markets, and educational institutions. The trends in Canada’s educational practices are greatly linked to occurrences in other countries. In this chapter, the focus will be on how educational practices in Canada are linked to larger global trends—particularly to the trend of neoliberalism. The chapter will examine how economic markets are linked to educational trends and changes over time. Attitudinal shifts that are influenced by the close relationship between such economic approaches and related orientations toward education and job training will also be considered.

Global Education

The term global education is one that is cropping up more and more in education-oriented literature. There is not a single definition of global education that is agreed upon by all users of the term, however. In general, global education refers to the delivery of education in a way that recognizes the context of subjects in a broader geographical framework than simply the one in which the students and teachers live. It is the recognition that topics should be taught from a perspective that acknowledges alternative approaches and promotes intercultural understandings. Sometimes global education may be referred to as development education, intercultural education, or world studies (Pike 2000).

While the goals of global education may be viewed as admirable, they are indeed difficult to put into practice and evaluate. This is due to many factors, not least because of the vagueness of the goals themselves and the uncertainty of how to put goals of global education into any meaningful sort of practice (Pike 2000). The idea of what global education entails differs between countries as well. For example, Canadian and British teachers are more likely to regard it as meaning the understanding of how people are connected to the global system, while American teachers are more likely to state that global education refers to learning about different countries and cultures (Pike 2000).

Citizenship Education in the Canadian Curriculum

One strategy of promoting global education is to augment civic education, social studies, and/or history (depending on the jurisdiction) with aspects of global citizenship education in the Grades 1 to 12 curricula. As noted by Richardson and Abbott (2009), it is more difficult to talk about global education in Canada than in countries like France and the UK, where national curricula exist. Curricula across Canada vary considerably. We can, however, examine how the different curricula respond to concerns over global citizenship.

Richardson and Abbott (2009) remind us that global citizenship is not a concept that is new to Canadian curricula and that the preferred relationship between students and the larger outside world is one that has changed over time due to various shifts in political outlooks of wider society. Richardson and Abbott (2009) identify five different major imaginaries in the approach of global citizenship education in Canada over time. Imaginaries are ways of understanding the nature of global citizenship and provide a rationale for promoting such a world view. Imaginaries do not necessarily follow a linear sequence, and elements of more than one may be found overlapping within the same curriculum in a province at any given time.

The first major imaginary is imperialism. In much of the twentieth century, emphasis was placed on teaching children about how to be proper moral citizens and to uphold allegiance to the British Empire. National identity as Canadians was largely framed in terms of imperialist connections to Britain. The world was essentially divided into recognized colonies of the Crown and “other” (Richardson and Abbott 2009), Commonwealth and non-Commonwealth, or “West” and non-West.

The next major imaginary was the Cold War, which refers to the period immediately following the Second World War (1945). Global citizenship education then focused on a different kind of “other.” The world was no longer was perceived to be divided into Commonwealth and non-Commonwealth, but was split into communist and non-communist. Much social studies curricula was focused on understanding the differences between the two worlds.

After the focus on the Cold War came the multipolar imaginary, which began in the 1960s. This understanding of the world was framed by the creation of the United Nations and the shift of Canada as a “rising middle power.” The multipolar phase switched the international discourse in curricula to one that focused on international co-operation and interdependence. These changing world views were also embedded in a changed technological landscape in which air travel and advances in telecommunication were contributing to a new “world culture” (Richardson and Abbott 2009:383). The view is also characterized as the “global village” understanding of the world, wherein the mandate of global civic education was to enlighten students as to the interdependent nature of global politics and the great inequalities that existed between nations, with the underlying objective to raise the standard of living in developing countries. While perhaps a noble ambition on the surface, critics (see Merryfield 2001) argue that such a world view is fundamentally the same as that found during the imperialism phase, when it was assumed that the West was a model for all others to follow, ignoring important cultural and historical differences.

The late 1980s saw the emergence of the ecological imaginary, which emphasized environmental concerns about the survival of the planet along with an understanding of cultural diversity and a respect for a variety of world views. Educational approaches focused on getting the student to see the world through the eyes of those from other cultures and nations. The ecological phase was a transformative approach to global citizenship education (Richardson and Abbott 2009) because its focus was on changing the world views of students and getting them to reexamine their own biases and beliefs, rather than changing other cultures.

The most current imaginary of global citizenship education is one that is characterized as monopolar. The prevailing approach that is taught is one rooted in economic neoliberalism, which emphasizes the understanding of the world as a vast market. The emphasis has shifted to the international competitiveness of markets, with consumerism as the core organizing principle. This imaginary, according to Richardson and Abbott (2009), is largely a step backwards in the evolution of such approaches to global citizenship education because it somewhat resembles the previous phases, which stress individualism and competitiveness rather that interdependence and empathy.

Richardson and Abbott (2009) argue that Canadian curriculum currently tends to exhibit characteristics of both the ecological and monopolar imaginaries, which is inherently problematic because of the opposing world views that they occupy. The ecological imaginary emphasizes an empathetic world view, while the monopolar focuses on competitiveness. For example, recent planning documents from the Ontario Ministry of Education state that “[t]he overall skill and knowledge level of Ontario’s students must continue to rise to remain competitive in a global economy. At the same time, the achievement gap must continue to be closed between students who excel and students who struggle because of personal, cultural or academic barriers.”1

Global Economic Crisis

Markets that are linked across borders are a key feature of the current world in which we live. The economic situation of a country determines many practices of its government and market behaviours of its citizens. The recent global economic crisis was a major event that had numerous knock-on effects in various aspects of social life, including work and education. Therefore, the global economic crisis is directly connected to the current state of education in Canada and around the world.

The global economic crisis began in 2008 and is much attributed to lending practices in the United States, characterized by an abundance of subprime mortgages. Subprime mortgages are loans for purchasing a home that are given to individuals who have higher credit risks and may have more difficulty meeting the repayment schedule. The price of houses at this time was also artificially high, meaning that a great number of large mortgages were given to individuals at a high risk of defaulting. These loans were bundled together and sold as securities to investors. When defaulting on the mortgages occurred in large numbers, many foreclosures occurred and the banks took over ownership of the houses. The foreclosures, however, became so numerous that housing prices dropped, affecting the prices of houses owned even by people with a low risk of defaulting. With the values of houses dropping around them, low-risk borrowers found that the houses they originally bought for higher prices were valued at only a fraction of what they paid, and the changing terms of their mortgages caused them to default as well. The banks were left holding properties that were nearly worthless and the investors owned securities with no value.

Because the banking and investments systems are linked throughout the world, it was not long before the crash in the US banking system was felt in other countries. Many banks were “bailed out” by federal governments, causing the governments to borrow money to rescue the established financial system. High government debts have many different ramifications for citizens, including higher unemployment and decreased spending on social programs.

More recently, the European debt crisis has been at the forefront of current affairs. Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain are four European Union member states that are heavily indebted due to borrowing from other countries. In many instances, the national debt of these countries can be linked to the financial crisis that began in the United States. These countries all faced the inability to pay back their debts, and so the European Union and the International Monetary Fund had to make a decision as to whether to bail them out and thus increase the debt for other EU member states. In the case of the European Union, the value of the common currency (the euro) is at stake in dealing with debt at the country level.

Economic Crises and Education

These economic crises are not simply problems with banking and trading stocks, limited to the realm of the financial sector. These problems spill over rather quickly into everyday aspects of citizens’ lives, particularly when governments declare austerity measures in which public spending is severely cut in order to pay back federal debt. These spending cuts can affect education systems because education systems are funded in part by these governments. In Canada, this has resulted in reductions in funding to higher education and research as well as hiring freezes at many universities and colleges. Many universities and colleges have also responded to funding cuts by increasing reliance on fixed-term and temporary contract faculty, which are less expensive to employ as they are paid lower wages and have little or no job security (Education International 2009; Rajagopal 2002; Webber 2008).

University budgets are also strongly tied to endowment funds, which are donations given to the university that are invested in the stock market. The university is allowed to use a percentage of the investment earnings from the endowment fund in its operating budget.

When the financial crisis began in late 2008, many stocks dropped in value, which also meant that the size of the university endowment funds also shrank. For example, in 2008 McGill University had $928 million in endowments, which lost 20 percent of their value (about $185 million).2 Endowment fund losses of similar proportions were seen at universities all across the country.

Usher and Dunn (2009) predicted that the economic downturn in Canada would present a number of challenges to post-secondary institutions, including decreased revenue combined with increased costs, increasing enrolments, and increasing costs associated with student financial assistance. These predictions paint a bleak picture for students competing to be enrolled in programs at post-secondary institutions, with a greater reliance on financial aid and questionable employment prospects upon graduation. Usher and Dunn (2009) indicate that economic recessions historically result in increased post-secondary enrolment due to limited employment opportunities in a difficult economy. Many such students favour short-term courses, like master’s degrees and college programs. Usher and Dunn (2009) predict that master’s-level programs will be characterized not by the seminar style of learning, but larger lecture-style arrangements that will be used to accommodate increasing class sizes.

Increasing tuition fees may be a necessary source of revenue for universities (Usher and Dunn 2009) as rates of federal and provincial funding for post-secondary institutions decreases. The Canadian Federation of Students (2008) reported that tuition comprised about 21 percent of university revenue in 1995, while it is currently around 32 percent.

Neoliberalism in Canadian Education

Many researchers argue that there has been a marked shift in the orientations of students toward education in the last generation, which is largely due to the increasing popularity of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism is the ideological belief in the reduction of public spending and the promotion of reliance on private enterprise within a global economy. This term comes from the classical definition of liberalism originating with the work of Adam Smith. Neoliberalism should not be confused with political liberalism, which generally reflects a progressive approach to social and fiscal policy that focuses on the community and is more closely related to social democracy or socialism. In terms of how neoliberal ideas relate to education, fiscally conservative governments will often cut funding to education, which results in increases to tuition fees.

Davidson-Harden et al. (2009) argue that neoliberal social policy started in Canada in the late 1990s—a bit later than in England and the United States—with massive cuts in federal transfers to the provinces by the federal Liberal Party, rationalized as part of a larger-scale deficit reduction program. These budget cuts affected many social welfare programs across the country and were framed as an attempt to “trim” the welfare state. These cuts in federal transfers resulted in reduced funding to all levels of education.

Neoliberal Practices in K–12 Education

In terms of K–12 education in Canada, some notable markers of neoliberalism have already been discussed in previous chapters. For example, in Chapter 4, the creation of “charter” schools in Alberta under the fiscally conservative Ralph Klein government of the 1990s was rationalized as a way to provide “choice” and “alternatives” to parents in terms of public education. It was also suggested that such alternatives put pressure on public schools to perform better so that they can still be seen as attractive to prospective students’ parents. The public funding of private education, which was also discussed in Chapter 4, and which varies from province to province, is also indicative of this understanding of education as a product that can be subject to comparison shopping.

As described in Chapter 5, many provinces are relying on standardized testing of children. Rezai-Rashti (2009) notes that standardized testing and evaluation systems were brought into Ontario during the Premier Mike Harris years, which were characterized by massive structural changes in governance, curriculum, and evaluation procedures. The structural changes were argued to reduce “waste,” while the evaluation and curriculum changes were adopted to increase accountability of teachers and to have precise records of students’ achievement.

Weiner (2003) indicates that public schools are increasingly relying on fundraising in order to meet the gaps left by provincial funding cuts. In affluent neighbourhoods, fundraising by students and parents can be quite successful and garner substantial donations, but schools in economically disadvantaged areas do not have this kind of success in fundraising initiatives. Davidson-Harden et al. (2009) suggest that this increased reliance on fundraising in K–12 is indicative of privatization in public schooling. People for Education (2011), an advocacy group for Ontario public schooling, found in a recent survey of parents of students in public schools and their principals that nearly all public schools in Ontario were involved in some form of fundraising that, per school, funds raised by such efforts varied from zero dollars to $275 000. Additionally, over two-thirds of secondary schools were found to charge fees for courses. New guidelines from the Ontario Ministry of Education are expanding allowable fundraising efforts to enable outdoor structures, renovations to auditoriums and science labs, upgrades to sports facilities, and investments in technology (Ontario Ministry of Education 2011). Such additional allowances on the spectrum of targets for fundraising suggest that the gap between the richer and poorer schools will expand further (People for Education 2011).

For-profit offshore schools were also discussed in Chapter 4 and can be conceptualized as another attempt to “sell” education. Offshore schools are, at the time of writing, an educational product that is permitted only by the Government of British Columbia in the form of “School District Business Companies” since 2002—when the idea was marketed to school boards as an entrepreneurial opportunity to make money abroad.3 Fifteen school boards acted on this opportunity, resulting in offshore schools around the world, but mostly in Asia.

Another example of the private market creeping into K–12 public education is illustrated in the creation of public–private partnerships, also known as P3s. P3s refer to contracts between the public and private sectors in which skills or investments are made by the private sector into a good that will be offered to the public. The private sector will recoup its investment through various means. For example, a private company may build a structure to be used by a school and then rent that property to the school. Perhaps the most “infamous” case of P3 schools occurred in the 1990s in Nova Scotia, when the Liberal government declared in 1997 that all new schools would be P3 schools—in other words, private companies would be used to build the schools and private companies would retain ownership over the buildings and the province would lease the buildings. A new Conservative government took office in 1999 and investigated the premises behind the new P3 decision. An auditor found that the proposed 38 schools that had been built the P3 way actually ended up costing the province $32 million more than if they had been built by the province. Additionally, the costs of repairs and upgrades to the leased buildings are often the responsibility of the public partner—not the private partner. After a lease of the property expires (typically 25–30 years), the province has the option to buy the building back from the private holder, thus assuming ownership of a 25- to 30-year-old building. P3s have been experimented with in many provinces, with varying degrees of success.

The final, and perhaps most obvious, example of neoliberal practices in K–12 education is advertising in schools. Like fundraising efforts, schools and school boards are frequently seeking additional ways to increase revenue to support programs and equipment that government funding does not cover. In a study of commercialism in Canadian public schools, the Canadian Federation of Teachers (Froese-Germain 2005) found that 28 percent of elementary schools reported advertising for corporations or businesses in or on the school. The respective figure for secondary schools was nearly doubled at 54 percent. According to results, “[m]ost advertising in elementary schools was found on school supplies (11.4%) and in hallways, cafeterias and other school areas (11.1%). In secondary schools, most advertising was found in school areas such as halls and cafeterias (31.5%) and to a lesser extent on school supplies (12.2%) and team uniforms (8.1%)” (Froese-Germain 2005:5). The most frequent corporate advertisers were identified as Coca-Cola and PepsiCo. In addition to advertising, many schools were reported to have “exclusive contracts” with either Coke or Pepsi such that only one of these brands would be sold on school property. Advertising in schools is a particularly contentious issue because while it may be a source of much-needed funding, critics argue that it is inappropriate to advertise products to children who are a captive audience inside an institution of learning. Froese-Germain (2005) states that there are at least three concerns that they have about advertising in schools. The first is that supporting unhealthy choices like sugary soft drinks may have health impacts on students, such as putting them at a higher risk of diabetes and promoting childhood obesity. The second reason is about equity—not all schools will be able to attract the same calibre and number of corporate sponsors, giving those schools that are already desirable to advertisers an even greater advantage. The final concern is one that questions the ethics of allowing corporate advertising in schools in the respect that the lessons that they learn in schools about good health and citizenship may be compromised by the very presence of corporate messages in the school corridors.

Neoliberal Practices in Post-Secondary Education

In terms of post-secondary education, there are also many indicators of neoliberal policy implicit in new trends on campuses. The most obvious shift in recent years is the decrease of government funding to post-secondary education and the increased reliance on tuition fees as a source of revenue, which is discussed elsewhere in this chapter. Another effect of neoliberalism, however, is the movement of provinces to approve the development of private, for-profit universities. The law permitting the establishment of private universities was passed in Ontario in 2002 (Postsecondary Student Opportunity Act), in British Columbia in 1985 (first the Trinity Western University Act in 1985, then the Sea to Sky University Act for Quest University in 2002),4 in New Brunswick in 2001 (Degree Granting Act), and most recently in Saskatchewan in 2012 (Saskatchewan’s Degree Authorization Act).5

Metcalfe (2010) argues that although Canadian governments have traditionally distanced themselves from outrightly favouring high-technology programs and promoting partnerships with industry (at least more so than their counterparts in other English-speaking countries), this is becoming more favoured as a source of revenue. The term academic capitalism has been used to describe national-level policies that favour industrial research collaborations, while often undertaken at the cost of revenues directed toward undergraduate education (Slaughter and Leslie 1997). Such targeted partnerships with industry are regarded by some Canadian professors as a threat to academic autonomy (Newson and Polster 2008) because the implications of such alliances will require researchers to pursue topics that are of interest only to businesses, marginalizing many of the research topics that are of interest (and concern) to faculty members. As pointed out by Metcalfe (2010), however, other researchers such as Pries and Guild (2007) are far more enthusiastic about the increasing role of commercialization within the university, understanding them as economically viable opportunities for learning. In addition to industry-funded research in the university, there has also been a noticeable increase in the presence of corporate members on university governance boards.

For example, the board of governors at the University of Calgary in the academic year 2011–2012 included the vice-president and chief financial officer of Shaw Communications and the former vice chair of Enbridge,6 while the board of governors in the same academic year at University of New Brunswick included the chair of BMO Asset Management and the former vice-president of finance for NB Power.7 Table 9.1 provides a list of corporate members of boards of government for a selection of Canadian universities in the academic year 2011–2012. Research by Carroll and Beaton (2000) has found that members of boards of governors at Canadian universities are increasingly from high-tech industry, signalling more reliance on technology-intensive production in global markets and neoliberal approaches to higher education that value such linkages between industry and universities.

Education researchers and commentators have also argued that another outcome of neoliberalism is that the fundamental purpose of higher education has also undergone an important (and undesirable) shift from education to training (Côté and Allahar 2011; Keeney 2007). The objective of education, as understood from a traditional “liberal education” perspective, is to cultivate the mind of individuals. The neoliberal agenda, however, has shifted this orientation of creating well-informed citizens to a framework of training students for jobs, which focuses on developing a narrow range of skills or specialization in particular tasks. Côté and Allahar explain that “one can only be educated in the liberal arts and sciences: education and training are not inimical to one another; they merely speak to different moments in the complex process of teaching, learning, and sharing information” (2011:15). This shift from universities providing a liberal education to a focus on marketable skills and training is referred to as vocationalism.

Table 9.1 Corporate Board Members at Selected Universities across Canada, 2011-2012

Sources: http://bog.ubc.ca/?page_id=84; www.ucalgary.ca/secretariat/node/627; www.queensu.ca/secretariat/trustees/bios.html; http://boardofgovernors.dal.ca/Board%20Members; www.mcmaster.ca/univsec/bog/membersbio.cfm

| UBC | University of Calgary | Queen’s University | Dalhousie University | McMaster University |

| Western Corporate Enterprises | Fraser Milner Casgrain LLP | Keystone Property Management Inc | Southwest Properties | Research in Motion (RIM) |

| Pushor Mitchell | Enbridge | Granite Microsystems | Doctors Nova Scotia | CIBC |

| Salient Group | Salman Partners | Black and Associates | Stewart McKelvey | Trivaris |

| Timber West Forest Corp | Western Financial Group | Bell Canada Enterprises | Canada Direct Trading Ltd. | Westbury International |

| Royal Bank | River Ridge Financial Management | McInnes Cooper | Gowlings Hamilton | |

| Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan | Bennett Jones LLP | Intelivote Systems Inc. | OMERS | |

| Russel Metals | Age Care Investments Ltd. | Halifax International Airport Authority | Craig Wireless Systems | |

| Borden Ladner Gervais | Canadian Energy Pipeline Association | M. Fares Group | Xerox Canada | |

| Canfor | Shaw Communications | Dofasco |

Evidence of vocationalism can be observed in the increased offering of diplomas and certificates (rather than degrees) in various fields that presumably signal training in a particular set of skills. Applied degrees are also fairly new arrivals to the university scene, with an “explosion of activity” around the creation of such degrees in Ontario, British Columbia, and Alberta (Dunlop 2004). Such degrees are different from the baccalaureate degrees traditionally awarded at universities and are similar in training to what used to be only conventionally available at community colleges (Dunlop 2004)—specific training in skills that are meant to lead directly to jobs. Community colleges in the same provinces also were given the authority to award baccalaureate degrees between the early 1990s and 2000, with New Brunswick and Manitoba following suit in 2008 and 2009, respectively (Jones 2009). Such changes in provincial legislation were often rationalized by provincial leaders as a way of making post-secondary education more market driven by increasing post-secondary competition and emphasizing individual choice (Skolnik 2008). It is also interesting to note that vocationalism of universities is also highly associated with the lessening prestige and emphasis placed on actual vocational training in the skilled trades at the secondary level, as discussed in Chapter 8 (Taylor 2005, 2010). Table 9.2 summarizes the different indicators of neoliberalism in Canadian education.

Table 9.2 Indicators of Neoliberalism in Canadian Education

| K-12 | Post-secondary |

| Decreased provincial funding | Decreased federal transfers |

| Increase in standardized testing | Increased tuition |

| Increase in private education | Increased reliance on part-time and contract faculty |

| Increase in alternative to public school (e.g., charter schools) | Increase in private universities |

| Increased reliance on fundraising by schools | Branding and marketing of post-secondary institutions domestically and abroad |

| Advertising in schools | Increase in corporate partnerships |

| High fees for international students | Increase in corporate membership to university governance |

| Offshore, for-profit schools | Increased reliance on international students as a source of revenue |

| P3 initiatives (public-private partnerships) | Vocationalism and “applied” degrees |

There is a great deal of controversy around the place of applied degrees, certificates, and diplomas within the university system. Traditionally, universities were places of “higher learning” and sites of liberal education, while colleges were places where students went for job training. Increasingly, however, this distinction is being blurred. Dunlop (2004) suggests that because many university graduates went on to “top up” their degrees with training at colleges after graduation, the university has found an opportunity to fulfill a market need. Others, such as Côté and Allahar (2011), find fundamental intellectual flaws in confusing the original mandates of universities and colleges:

. . . to dismiss this distinction and embrace the confusion between education and training is analogous to confusing an apple with an orange. Both apples and oranges are good in their right. But to shift a liberal education system to a vocational one, and then claim the benefits of the liberal education for pseudo-vocational training is not only mistaken, it is dishonest. If we continue to delude ourselves about this, not only will the system degrade further, but also the mixed system we are developing will diminish further the overall legitimacy of the system in the eyes of stakeholders who count on the quality of liberal arts and sciences graduates and the roles for which they are ostensibly certified. (Cote and Allahar 2011:103)

Students as Consumers?

Under neoliberalism, education is seen as a means toward getting a job at an increasing rate of tuition. Education then becomes reframed as a product that is purchased rather than a public good to which all citizens should have access. This has led to a view that students are “consumers” in post-secondary institutions, trying to get undergraduate degrees that are increasingly regarded as the minimum education required to enter the corporate world. As argued by Côté and Allahar (2007), the university in particular has shifted from a place of “elite education” to that of mass education. Participation rates in post-secondary education have increased greatly over the past 20 years, as detailed in Chapter 8. The decreasing per-student amount that is government-funded and the increased number of students has forced post-secondary institutions to find other sources of revenue, including increased tuition fees. Students are more likely now than in the past to perceive a university degree as the necessary minimum credential for getting a good job—a credential that comes with an increasingly hefty price tag. See Box 9.1 for a discussion of universities competing for students.

This view of students as consumers who must be satisfied with the product they have purchased stands in stark contrast to traditional models where teachers and professors are the authority figures in charge of the learning. Such orientations can (and do) result in a clash between teaching staff and students. Newson (2004:231), for example, argues that students who view themselves as consumers may argue that they should not have to participate in class (showing up should be enough) and that their tuition entitles them to a “decent” grade. Wellen (2005) argues that the frustrated responses of teaching staff can play themselves out in the form of “arrogance and condescension,” or professors may instead change the course style and delivery to one that is more entertaining and practical, thereby marginalizing academic values while prioritizing ones that will appease students. This is particularly poignant given that student evaluations of teaching are often used as part of the tenure and promotion process of professors (Lindahl and Unger 2010). Junior faculty members are more likely to feel pressured to please their students, even at the cost of their course content.

Box 9.1 – Universities Competing for Students

The annual rankings of universities in Maclean’s magazine has been a popular benchmark by which to judge universities since they were launched in 1991. The rankings are broken down into a variety of areas, including classes, student–teacher ratio, grants and awards received by faculty members, resources, student support, library facilities, and overall reputation. The ranking exercise has not been welcomed by all university administrators, who have argued that past ranking methodologies are flawed. In 2006, 25 Canadian universities refused to participate in providing Maclean’s with the data they requested to do the rankings. Such universities included the University of Alberta, Dalhousie, the University of British Columbia, and the University of Toronto (Samarasekera 2007). Maclean’s has bypassed this obstacle in successive years by not requiring the universities to provide data, instead getting it from public sources, such as Statistics Canada and university websites.

But how important are these rankings? Do they influence students’ decisions when selecting a university? Mueller and Rockerbie (2005) find that a university’s Maclean’s ranking can significantly impact upon the number of applications that it receives. In terms of how the universities themselves respond, the evidence is less clear.

Senior administrators at UBC were very concerned about their Maclean’s ranking on class size in 2003 and they “pressured faculty members to manipulate course enrolments and even cap class sizes in an effort to improve the school’s standing in the Maclean’s ranking—despite warnings from professors that this could actually hurt students. Internal documents revealed that the administration suggested using sessionals to teach classes, lying to students about room capacity even if it meant denying students the opportunity to major in a discipline or graduate on time. UBC actually designed an enrolment software program to help department chairs cap enrolment at the numbers set by Maclean’s” (McMurtry 2004:20).8

Another way that universities are competing for students is through branding. Branding refers to the process of creating a public image that is advertised and associated with a specific product or service. Varsity clothing lines are a traditional style of higher education branding, but in more recent years, full-blown ad campaigns for universities have been rolled out, ranging from movie trailers, billboards, and ads on public transportation, to banner ads on websites and direct marketing. Many larger universities in Canada spend $1 million or more on advertising per year.9 It is difficult to assess how successful such ad campaigns are, and critics argue that such large expenditures on advertising are drawing precious resources away from current students. This, in turn, creates a vicious circle of having to recruit even more students to fill this revenue gap.

While the figures for Canada are not easily aggregated, in the United States, the amount of money spent on marketing of universities and colleges went up by 50 percent between 2000 and 2008 (Hearn 2010). Hearn argues that university branding campaigns “replace traditional mottos with pithy slogans. Some of these include ‘A Legacy of Leading’ (University of Idaho); ‘Redefine the Possible’ (York University); ‘Inspiring Minds’ (Dalhousie University); ‘Inspiring Innovation and Discovery’ (McMaster University); ‘Open Minds, Creating Futures’ (Ohio Dominican University); ‘Grasp the Forces Driving the Change’ (Stanford University); ‘Knowledge to Go Places’ (Colorado State University); ‘Investing in Knowledge’ (University of Liverpool); and ‘Wisdom. Applied.’” (Ryerson University)” (2010:210). A recent rebranding of the motto of Trent University from “Canada’s outstanding small university” to “The world belongs to those who understand it” resulted in a backlash from some students who regarded the new slogan as elitist. The new slogan was also marketed just before tuition hikes, resulting in one sign being vandalized to read “The world belongs to those who can afford it.”10

Globalization and Internationalization

In a previous chapter, globalization was defined as the increasing economic, technological, cultural, and migratory linkages of countries throughout the world.

The discourse of globalization favours the view that knowledge and knowledge workers will make positive contributions to the economy and that education is the vehicle by which such gains will be made. Education, however, is also becoming a lucrative business opportunity for many countries. The growth of private education, offshore education, and other for-profit education services has been noted by scholars of global education (Heyneman 2001) as well as elsewhere in this book. See Box 9.2 for a discussion of how the European Union member states are using globalization strategies in their restructuring of tertiary education.

Box 9.2 – The Bologna Declaration

The Bologna declaration is an example of a globalization strategy for education of residents of the European Union member states. In 1999, a declaration was made by EU leaders to increase the comparability of post-secondary education and credentials across Europe. These policies were adopted in order to increase the mobility, employability, and competitiveness of higher education in the European Union (Bologna Declaration 1999). Reforms at the national level are envisaged to promote mobility for students and academic workers within the European Union (Pechar 2007), thereby creating more fluidity between national systems and bypassing traditional barriers of fragmentation between education systems in the individual member states. Such a vision for large-scale mobility is thought to be largely influenced by the model in the United States (Pechar 2007). One major outcome of this agreement is rooted in the very organization of degrees in member states; restructuring to the Bologna standards requires institutions to adopt the “Anglo-Saxon” arrangement in which an undergraduate degree is followed by a master’s degree and then a doctorate. Prior to this, the systems in each member country had been a “mishmash” of different degree structures, often with first degrees equivalent to master’s degrees which required six to seven years of study (Pechar 2007). Under the Bologna declaration, the first “cycle” (undergraduate) lasts three years at minimum, although no length is set for the second cycle (master’s). Additionally, the comparability of national systems is further facilitated by the European Credit Transfer System, which permits students to accumulate credits while transferring to universities in different member states, further promoting European mobility of students.

In the past few decades, trade agreements have been signed between countries that actively promote this notion of globalization, encouraging (even requiring) trade between countries with fewer barriers. The World Trade Organization (WTO) was established in 1995 and currently has 153 member countries, with Canada having been a member since its founding.11 The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) is a multilateral trade agreement pertaining to “trade in services” and was created to “liberalize” such trade in services around the world. The agreement specifically defines restrictions on government measures that may impact on the international trading of services and are legally enforceable through trade sanctions if deemed necessary. The development of the agreement continued in the early 2000s, and only explicitly eliminates government/public services from the process of liberalization.

GATS has caused considerable unease among education researchers worldwide because it is understood as much more than just a trade agreement, but covers every possible manner in which services are provided internationally. Because the agreement openly advocates privatization and deregulation, many critics argue that there are potential risks to higher education (Robertson 2005). If higher education is deemed to be a liberalizable service or commodity that is subject to GATS, there are possible implications for future restrictions and regulations regarding the presence of foreign institutions, tax rules, and restrictions of research grants to domestic universities (CAUT 2012). The GATS does indicate that “services supplied in the exercise of governmental authority” are exempt from GATS, which should cover public higher education in Canada. The Canadian Association of University Teachers (2012), however, argues that the extent to which higher education is public (i.e., subject to governmental authority) varies considerably among countries, with private and public systems existing in many nations. Critics argue that many clauses in this agreement need to be clarified so that the position of higher education in this trade agreement is explicit. Drakich, Grant, and Stewart (2002) suggest that the presence of the private American university, the University of Phoenix, in Canada indicates the liberalization has already begun, despite the Canadian government’s assurance that public education was not subject to such bargaining. The private American post-secondary provider the DeVry Institute of Technology has also made recent inroads into Canada, with its most recent campus established in Calgary.

Many Canadian post-secondary institutions are involved in an ongoing strategy of promoting internationalization. Internationalization in general refers to the process of creating co-operation and activities across national borders (van der Wende 2001). The internationalization of education is the process of creating linkages between educational institutions and people that span across borders. While internationalization and globalization (Chapter 8) are often used interchangeably, there are important differences between them. One key difference is that internationalization can be seen as an expression of national self-interest where the nation is a dominant feature. While there may be benefits to individuals from other countries, the basic unit of interest in internationalization is always the individual country. Globalization, in contrast, is oriented toward replacement of national economies with a single global economy characterized by free movement of individuals and capital. The two terms globalization and internationalization are most certainly linked in meaning, but the latter is ostensibly rooted in very specific interests of the state.

Farquhar (2001) has identified four rationale-types for the internationalization of Canadian universities (see also Cudmore 2005a for further discussion). The first is a culturally based rationale, which argues that internationalization will permit Canada’s culture to be more widely (in a global sense) understood. With this understanding will come a higher respect for Canada’s values, which will lead to Canada having more global influence. The second is a politically based rationale, which is concerned with issues such as national security and strategic alliances. International students in Canada can be regarded as potential future citizens who may become part of Canada’s highly skilled workforce. The third is an academically based rationale in which it is surmised that internationalization necessarily adds international elements to the curricular activities, which in turn enhance the academic experiences of both foreign and domestic students. The final rationale is economically based and argues that internationalization is associated with the greater economic performance of a country.

Transnational and Cross-Border Education—The Future of International Studying?

The widespread availability of online technologies and distance learning opportunities offered by increasing numbers of post-secondary institutions around the world means that it is often possible for students who reside in one country to obtain credentials (including degrees) from institutions in different countries without leaving their original country of residence. The term transnational education is often used to describe the educational arrangement where students are physically located in a different country than the credential-awarding institution (van der Wende 2001). Anglo-Saxon countries are the main deliverers of transnational education, with the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia being the world’s dominant providers (van der Wende 2001).

In contrast to transnational education, cross-border education occurs when the host institution essentially becomes mobile (instead of the student). Cross-border education can take several forms. Sometimes post-secondary institutions open branch or satellite campuses in foreign countries where they deliver the same (or similar) degree programs that are offered at the home or main campus (Marginson and McBurnie 2004). For example, the Schulich School of Business at York University is building a campus in Hyerabad, India, scheduled to open in 2013. Although the York business school has been offering its curriculum and degrees to students in India for the past three years through a partnership with the SP Jain Institutive of Management and Research, they believed demand was high enough to necessitate the creation of an entire branch campus in India.12

Other branch campuses of Canadian universities include the United Arab Emirates campus of University of Waterloo (see http://uae.uwaterloo.ca/) and the Qatar campus of University of Calgary (http://www.qatar.ucalgary.ca/). The University of Calgary’s branch campus offers nursing degrees to students in Doha, Qatar. Waterloo’s branch campus is in partnership with HCT-Dubai in UAE. According to University of Waterloo:

“The University of Waterloo offers programs on the campus of HCT-Dubai, with students transferring to the university’s main campus in Waterloo, Ontario after two years to complete their studies. All teaching personnel at the university’s campus in UAE come from the Waterloo campus. The curriculum for programs offered at the UAE campus is identical to the curriculum for the same programs offered in Waterloo. In addition, the UAE campus offers the same cooperative education program. Because HCT recognizes all credits earned in University of Waterloo programs, graduates who have completed the necessary requirements at the UAE and Waterloo campuses will receive both an HCT degree and a University of Waterloo degree. The university does not make a distinction between the degrees earned by those studying full-time at the Waterloo campus and those who have completed part of their studies at the UAE campus.” 13 (Copyright © University of Waterloo)

In addition to branch campuses, other universities are in formal partnerships with post-secondary institutions in other countries. Partnerships are different from branch campuses because the university does not commit to building a physical location on foreign soil. For example, University of British Columbia has a partnership with Mexico’s Tecnologico de Monterrey in 1997 (Bates 2001). Staff at UBC developed five online courses which were then developed in the curriculum at Tec de Monterrey, with the costs of development shared equally by both institutions. Tec de Monterrey was allowed to use these courses anywhere in Latin America, and UBC could also use these course materials elsewhere in the world. After five years, the two institutions decided to enter into a formal partnership, in which both institutions offer a master’s degree in Educational Technology that is available in both English and Spanish, with faculty at both institutions working together on courses.14

Another way that post-secondary institutions establish themselves in foreign markets is through the use of franchising. As the term suggests, “a local service provider is authorized by a foreign institution to provide all or part of one of its education programmes under pre-determined contractual conditions. Most of the time, this education leads to a foreign qualification” (Vincent-Lancrin 2009:70–71). At the time of writing, Canadian universities have not participated in franchising arrangements to any significant measurable extent, although such practices are very common with British, Australian, and American universities (Healy 2008). The practice of franchising has also been disparagingly referred to as McDonaldization (Hayes and Wynyard 2002) because critics argue that this method of market expansion used by such universities and colleges is akin to equating education with the products offered at globally present chain stores and restaurants. In fact, one of the major debates around the franchising of universities and colleges, particularly to major markets in Asia (China, Singapore, and Malaysia) has been the lack of quality assurance measures taken to ensure that the education and degrees awarded at such franchises are actually equivalent to those awarded at the original “home” institution. At the heart of franchising is the idea that a product is universal wherever it is consumed—a Big Mac is the same product in every country. The number of students in franchised university programs is not inconsequential—for example, even in 2002, over 180 000 students were reported to be in franchised UK universities abroad (Healy 2008). Quality assurance practices have become more commonplace, sometimes revealing significant deficiencies in the way programs are delivered abroad. In a particularly embarrassing investigation, for example, a Malaysian campus that awarded University of Wales degrees was found to be run by a local celebrity with faked credentials, while another franchise in Bangkok was found to be running illegally. As a result of this (and other irregularities within the University of Wales), the university has been closed.15

The Recruitment of International Students

Another revenue-creating technique being used by many universities is the recruitment of international students, who are usually required to pay a fee differential, or a rate of tuition that is higher than (sometimes double) that of domestic students. These differentials were brought in by various host countries due to the perception that there were substantial costs associated with subsidizing students from other countries (Woodhall 1987). Introduced in Canada in the 1970s, individual jurisdictions all have different fee structures for international students. In Quebec, however, international students are often not subject to fee differentials due to the province’s official policy of recruiting francophone students from other parts of the world (Eastman 2003, cited in Siddiq, Baroni, Lye, and Nethercote 2010).

Differential fees are a substantial source of revenue for universities, and international students are aggressively recruited due to the high profits they afford many post-secondary institutions—not only in terms of the higher tuitions they pay, but also due to the relatively low cost of hiring these students as research and teaching assistants (Altbach and Knight 2007). For example, universities in Nova Scotia collected almost $19 million in such fees during the 2008/2009 academic year (Siddiq et al. 2010). The charging of differential fees to international students is a practice that currently occurs only in Canada, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and Australia. On post-secondary campuses across Canada, there are over 90 000 full-time and 13 000 part-time international students, representing nearly 10 percent of the undergraduate student body and around 20 percent of post-graduate students. International students contribute about $6.5 billion annually to the Canadian economy.16

Critics of fee differentials argue that universities use international students as a source of revenue while ostensibly hiding behind an official ideology of cultural

enhancement in which the recruitment of international students is promoted as fostering a multicultural environment that will augment the educational experiences of both foreign and domestic students. The Canadian Federation of Students (2008) is highly critical of fee differentials, arguing that such practices limit education-based emigration to students from wealthy families.

While international higher education is growing in demand, Canada receives relatively few of the international students who choose to study abroad (Weber 2007). In overall percentages, the United States receives 30 percent of all international students, followed by Germany and the UK (each with 12 percent), Australia (10 percent), and France (9 percent). Canada has only less than one percent of the total global share of international students at the post-secondary level (Weber 2007). The Canadian government introduced off-campus work permits to international students in 2006, hoping to increase the attractiveness of Canada as a study-abroad destination (Citizenship and Immigration Canada 2006).

Internationalization of the Post-Secondary Curriculum?

While some approaches to global education at the primary and secondary levels of education were discussed above, the mandate of attracting international students from abroad is often couched in the rationale of adding diversity to university campuses. Inherent in such discussions is the desire to add a global dimension to the education experienced by post-secondary students, both foreign and domestic. But how successful are Canadian post-secondary institutions at increasing not only the composition of their student bodies, but also the international and intercultural dimensions of their courses and programs? In 2000, 60 percent of post-secondary institutions in Canada that were surveyed in an Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada report (AUCC) indicated they did not have any way of monitoring or assessing the international dimensions of the programs or courses offered at their institutions, with only a quarter of universities indicating that a review process was being developed and just 15 percent stating that a process was already in place (Weber 2007). Such results suggest that a low priority has been given to some of the purported benefits of internationalization (Knight 2000). An update of the survey in 2006 (AUCC 2007b) provides little comparative data. Between the two years, universities that offer programs with an international focus grew from 53 to 61, and the overall number of academic programs with an international focus climbed from 267 to 356. However, university programs requiring graduates to have knowledge of a second language decreased from 16 percent to 9 percent.

There exists scant research on the internationalization efforts on Canadian campuses with regard to how successful they have been at incorporating intercultural and international perspectives. A handful of case studies appear in the literature, however. Hanson (2010), for example, describes an internationalization attempt at a global health program at University of Saskatchewan, citing evidence of “global citizenship” and “personal transformation” in students who had taken the courses. An additional issue in internationalization also relates to individual disciplines and how much internationalization is indeed possible in their fields. Some programs may lend themselves more readily to internationalization of the curriculum (e.g., cultural studies, sociology) than others (e.g., mathematics, biology). Indeed, the AUCC (2007a) found that the five most popular disciplines reporting successful internationalization of their curricula were global studies, European studies, international business, development studies, and Asian studies—disciplines that by their very nature are rooted in global conceptualizations of their subject matter.

In terms of the reported strategies that are most frequently employed in university efforts to internationalize the curriculum, the use of international scholars and visiting experts, the use of international or intercultural case studies, organizing international field/study tours, and encouraging students to work or study abroad were the techniques most frequently identified by Canadian university administrators (AUCC 2007a).17

Online Learning

While most Canadian universities offer some online courses, a few offer entire degrees that can be completed online. Indeed, student services such as advising and library services can also be done entirely online without the need for students to ever physically visit the degree-granting campus. There are two universities in Canada that are devoted entirely to online delivery: Athabasca University (in Alberta) and TÉLUQ (attached to l’Université du Québec à Montréal). Royal Roads in British Columbia also has a high proportion of its course delivery online, but brief periods of residency are required.

In terms of other universities that offer online courses, Memorial (Newfoundland), Thompson Rivers (BC), Manitoba, Waterloo (Ontario), Laurentian (Ontario), and Concordia (Quebec) offer the largest numbers of courses online (Canadian Virtual University 2012).

Canadian Virtual Universities is a consortium of English and French universities in Canada that came together to share resources and facilitate credit transfer across jurisdictions (CVU 2012). Students may be wary of acquiring online credentials because of the negative association such degrees have with US-based for-profit online universities (such as the University of Phoenix). CVU (2012) argues that Canadian universities would benefit from promoting the fact that quality assurance, transferability, and course comparability are ensured through member universities of CVU.

Most CVU students are domestic, with only a very small percentage (one to three percent) taking the courses and degrees from a different country. In contrast, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia take a much greater global share of international students who reside outside of the country’s borders (CVU 2012). There are many potential reasons for the relatively low uptake of Canadian online degrees by non-resident international students compared to other countries, including the prestige associated with particular institutions in the United States, UK, and Australia, legal and financial restrictions, and differences in professional accreditation (CVU 2012).

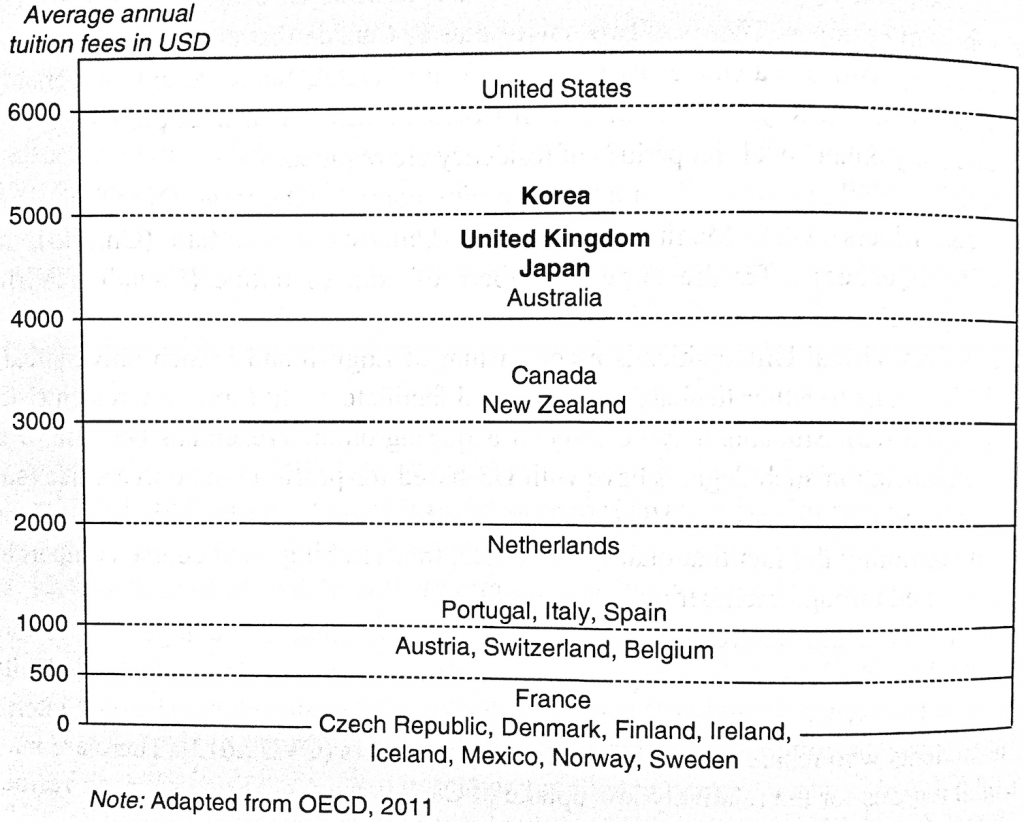

Rising Costs and Shifting Attitudes

As described above, changes in government policies and funding have meant that tuition fees have been rising for students, as the portion of governmental funding to post-secondary educational institutions has slowly shrunk over the past few decades. Still, however, Canadian university tuition fees are substantially lower than those found in other English-speaking countries, apart from New Zealand (OECD 2011), as shown in Figure 9.1. Recent fee restructuring changes in the United Kingdom that will be implemented in the academic year 2012–2013 will also substantially increase the distance between the tuition charged to UK-based students and those in Canada, as the Conservative government in the UK voted to remove tuition caps, which allow universities to charge a maximum of £9000 per year (approximately $14 000 CND). The maximum fee that UK universities were allowed to charge in 2010–2011 was just over £3000. Of the 123 universities in the UK, over half have announced that they will charge the maximum fee, while none have indicated they will charge less than £6000 per year.18

The OECD (2011) has identified four models of how countries approach funding tertiary education (see Table 9.3). Countries are divided into the four models according to how much of the cost of tertiary education is derived from tuition, how much student aid is available, the rates at which young people participate in tertiary education, and the overall public expenditure (as measured by GDP spending on tertiary education). Models 1 and 4 are similar in the respect that they charge very low (or no) tuition fees. Model 1 is comprised of the Nordic countries, which are often characterized by their deeply rooted social values that emphasize equality of opportunity, framing access to tertiary education as a right rather than a privilege. These countries often offer high student aid (to support students through their studies). Public expenditure on tertiary education is high, and is obtained through the higher taxation systems in these countries. To contrast, the various countries in Model 4 have low tuition, but also traditionally low levels of student aid. The participation rates in tertiary education are also much lower than in other models—less than 50 percent. Clearly there are factors other than tuition fees that influence students in these countries to go on to tertiary education.

Countries in Model 2 are the English-speaking nations and the Netherlands (which only recently joined this group). Students in Model 2 pay high tuition fees and have high access to student aid. There is also high uptake of tertiary education and relatively low to moderate public expenditure on funding for post-secondary education. In contrast, students in Model 3 in Japan and Korea pay high tuition fees and have little access to student aid. The participation rates in Japan and Korea also vary significantly, and recent reforms in 2009 to the student support system suggest that Japan may soon be more like a Model 2 country.

Match the model of education to the country clusters.

[h5p id=”9″]

Consumerism, Academic Entitlement, and Disengagement

Model 2 countries’ increased reliance on funding tertiary education by private tuition has led to an increased financial burden carried by students. Essentially, education is something that is becoming expensive to purchase. And there is an increasing perception that an undergraduate degree is an essential educational credential that is required for entry to the labour market, resulting in the steady increases in tertiary enrolment that are observed in the last 20 years—22 percent of adults aged 20 to 29 in 1995 to 26 percent in 2008 (OECD 2011). These increased enrolments, along with the cultural belief that having a degree is essential for getting any kind of “good” job later on, have been referred to as the massification of education (Mount and Bélanger 2004). As noted earlier in this chapter with regard to the discussion on neoliberalism, critics have argued that this focus on the cost of education is changing the expectations that students have about their post-secondary experiences, transforming them from students into consumers. Many post-secondary institution administrators are even referring to students as clients, reflecting a general shift toward reconceptualizing the role of students in institutions of higher learning. The shifting role of student from “empty vessel to be filled with knowledge” to a demanding consumer is resisted by many faculty members, however. For example, Newson (2004) argues that it is fundamentally erroneous to consider students as consumers or clients because they are simply not free to choose what they learn and how they learn it (this is still the domain of the teaching faculty). Additionally, the “product” of an education is not something tangible, but is the ongoing transformation of the student through learning, not simply the degree that she or he has paid for.

In a survey of faculty and librarians conducted by the Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations (OCUFA) in 2009, nearly 62 percent of respondents indicated that their class sizes had increased compared to just three years ago. Additionally, 40 percent indicated that they believed students were receiving less educational quality than just three years ago, pointing to oversubscribed courses where there were more students than available seats, large lecture-style courses replacing small-group seminars in upper year courses, and more reliance on multiple-choice style testing to ease workload. In addition to perceived deteriorating teaching conditions, 55 percent of respondents said that current students were less prepared for university than students just three years ago. Signals of this unpreparedness included clear declines in writing and numeric skills, expectations of success without effort, and overdependence on online sources rather than proper library research.19 Indeed, a literature is currently growing on the perceived unreadiness of new undergraduate students (see Côté and Allahar 2007, 2011), arguing that students are not being prepared in secondary school for the types of skills that have traditionally been assumed by university teachers in the past.

Professor Alan Slavin, a physics professor at Trent University, was interested in understanding the increased rate of dropouts from his introductory physics courses over recent years (Slavin 2008). He suggests that there are a few possible reasons for such increases. The first is grade inflation in high schools. Grade inflation refers to the increase in overall scores being given to work that in the past would have received lower grades. And, indeed, other authors (Côté and Allahar 2007, 2011) point to strong evidence of grade inflation over the past two decades: a grade of “A” meant “excellent” in previous generations, but is now considered “respectable.”20 And while there is widespread consensus that there has been grade inflation in the United States, Australia, the UK, and other countries, it appears that little is being done to stop it (Côté and Allahar 2011). Such critics argue that the result of grade inflation is that students are highly rewarded in secondary school for substandard work with minimal effort and experience a shock when these types of grading techniques are not carried over into university practices. Slavin (2008) also suggests that secondary schools have tended to rely on rote memorization of “facts” rather than developing critical reasoning skills due to the emphasis on performing well on standardized tests at the secondary level—a shift that occurred in Ontario in the 1990s during the first stages of neoliberal reforms.

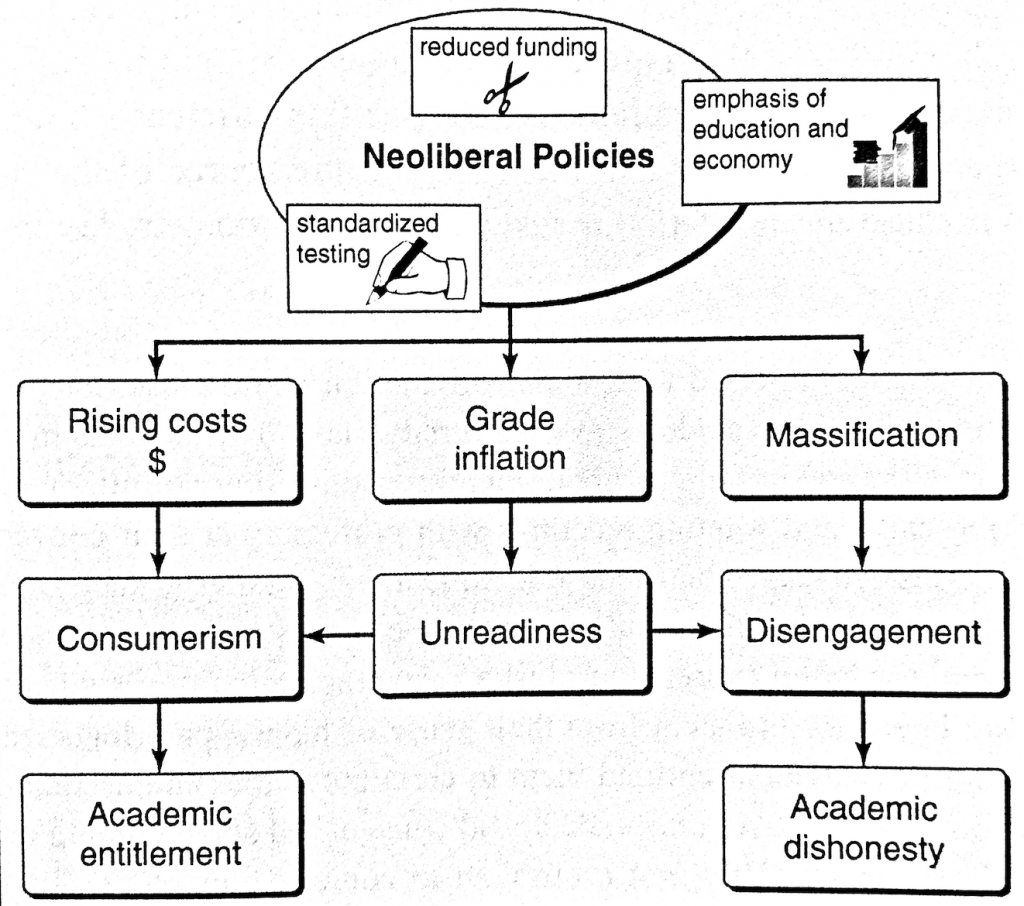

Figure 9.2 illustrates how the various terms described in this section are related to one another (according to the research of the many authors discussed here) and how they can be thought of as outcomes that originate from neoliberal policies.

Some Canadian universities have recognized that grade inflation is a problem and are changing the way that they assess undergraduate applications. The University of British Columbia is now requiring students to submit a personal profile in addition to their high school marks. The profile consists of answers to five short answer questions in which an applicant’s non-academic strengths may be evaluated. And because students’ final grades in Alberta are heavily impacted, and generally reduced, by their performance on standardized diploma exams, the University of Saskatchewan is now looking at both the high school marks and diploma exam marks of applicants from Alberta so that they are not disadvantaged relative to students from other provinces where such diploma exams are not used or factored so heavily into final grades (Tamburri 2012).

Faculty members and students also differ on their understanding of what constitutes a good grade, likely due to a combination of the history of grade inflation and the increasing expense of tuition. The term academic entitlement has been used to describe “an attitude marked by students’ beliefs that they are owed something in the educational experience apart from what they might earn from their effort” (Singleton-Jackson, Jackson, and Reinhardt 2010:343). In a focus group study of first-year students at the University of Windsor, Singleton-Jackson, Jackson, and Reinhardt (2010) found considerable evidence of attitudes toward academic entitlement, often captured in the sentiment that students should at least be expected to pass given that they pay such high tuition fees. The responsibility for passing appeared to be transferred to the professor, who participants in the study thought should recognize their payment and grant them a pass—a great departure from the professorial perspective that students should be evaluated based on their performance of the course requirements. Despite this difference, however, Singleton et al. (2010) argue that it is likely that the system is the source of the entitled feelings among students because the institution treats students as customers, leading to customer-like expectations:

Students’ comments indicated a customer orientation about class time, classroom etiquette, and their role as students in a university class. The students in this study did not express their expectations about email response time, turning assignments in late, taking calls, and wanting meetings with professors at their convenience in an overtly aggressive way. Their tone was, in fact, very matter of fact. Upon listening to the discussion recordings and reviewing the comments made by the students, we heard what was being expressed as just a very pragmatic set of student expectations that we interpreted to stem from their sense of having paid for attending the university and that payment entitled them to certain services and accommodations from their professors. . . . As one student said when asked about coming late and/or leaving early for class, “[It’s] not a problem to come late or leave early because we’re paying for it, so it’s our issue, but don’t be disruptive. (Singleton et al. 2010:352–353)

The idea of consumerism and these sentiments of academic entitlement are strongly linked to one another. Canadian researchers have called this phenomenon degree purchasing, wherein the credential of getting a degree is seen as a vehicle for employment opportunities rather than as an opportunity for learning (Brotheridge and Lee 2005). Canadian research has found that students who had strong degree purchasing orientations also had poorer study habits, performed poorly in courses, and were more likely to challenge the authority of their teachers (Brotheridge and Lee 2005).

Another concern for post-secondary teachers is student engagement, which refers to the amount of time and effort that students put into their studies. Côté and Allahar (2011) demonstrate that the amount of time students spend on their studies outside class has dropped significantly since the 1960s, when it was around 40 hours, to now, when it is around 14 hours. The authors explore different arguments for this change in study time, including the possibility that students’ time is now spent in paid employment or caring for dependants; however, their analyses of the National Survey of Student Engagement reveal that there is little association between time devoted to study and paid employment. If anything, their data indicate that those who work were more engaged. In contrast, time spent socializing was found to have a bigger effect on time displacement from studying. Most strikingly, however, was the finding that a great proportion of students who were disengaged reported receiving consistently high grades, suggesting that they were being highly rewarded for their marginal efforts. The authors suggest that such a finding points to fundamental flaws in the grading standards being used at Canadian universities today and in the expectations of professors.

Table 9.4 Forms of Academic Dishonesty Reported by Canadian University Students

| Type of Cheating | In High School | Undergraduate | Graduate |

Serious cheating on tests:

|

58% | 18% | 9% |

Serious cheating in written work

|

73% | 53% | 35% |

Source: Christensen Hughes, Julia M. and McCabe, Donald L. 2006. Academic Misconduct within Higher Education. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 36(2): 1–21 Reproduced with the permission from the Canadian Society for the Study of Higher Education/Canadian Journal of Higher Education

One additional symptom of student disengagement is academic dishonesty, more commonly referred to as cheating. In a recent study by Christensen Hughes and McCabe (2006b) of university students across Canada, undergraduate students were asked about their current studies as well as their behaviours in high school. The researchers asked the students about various forms of cheating, ranging from “mild” (e.g., working on an assignment with others when the instructor had indicated individual work) to serious (e.g., copying on an exam). Table 9.4 summarizes the numbers of high school, undergraduate, and graduate students who admitted to serious cheating on tests and written work. In terms of serious cheating on tests, 58 percent of students said they had engaged in a form of serious cheating on test while in high school, while 18 percent of undergraduates and 9 percent of graduate students admitted to serious cheating on tests. With regard to serious cheating on written work, nearly three-quarters of students indicated that they had done so in high school, while over half of undergraduates admitted to serious cheating while in university. Over a third of graduate students indicated they had participated in serious cheating on written assignments. While the authors caution that the results are not generalizable to all students in Canada, they suggest that the findings point to potential areas of concern.

Which students cheat and why? Christensen Hughes and McCabe (2006b) found that cheating occurs more among students who are young, male, overworked, have a different first language from that of instruction, suffer from anxiety, or have high grade-point averages. The latter characteristic—having high grade point averages—might be regarded as counter-intuitive; however, students may use cheating as a technique to ensure that they receive an A, particularly during high-pressure times in the school year.

There is also some consensus that the most pervasive form of plagiarism is copying from online sources, which is likely due to the accessibility and structure of the internet itself, constituting a type of “electronic opportunism” that many students might not be able to resist (Rocco and Warglien 1995; Selwyn 2008). Indeed, many universities in Canada and beyond have reported marked increases in plagiarism in recent years since the accessibility and availability of online information has increased. For example, in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at the University of Toronto, cases of online plagiarism rose from 55 percent of academic misconduct offences to 99 percent between 2001 and 2002 (Wahl 2002). Other researchers have suggested that students regard online plagiarism as less wrong than offences using sources that are in print (Baruchson-Arbib and Yaari 2004). Other commentators on the issue argue that such pervasiveness in online cheating is a byproduct of university massification (Breen and Maassen 2005; Underwood and Szabo 2004), whereby students feel increased pressure to get the highest grades possible. This may be compounded by perceived inadequate access to professors and libraries, reframing cheating as a required “survival strategy.”

Similarly, a study of students at a western Canadian university also examined cheating behaviours of undergraduates. Jurdi, Hage, and Chow (2011) asked students to reflect on their academic honesty since they began university and found that 30 percent of students admitted to plagiarizing written assignments, while a quarter indicated they had cheated during tests. Just over half of all students indicated that they had committed at least one instance of paper plagiarism, exam cheating, or falsifying records/making dishonest excuses.