7 Structural and Social Inequalities in Schooling

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to

- Describe how gender differences exist in educational outcomes.

- Explain how the socioeconomic status of a family can impact on a child’s educational outcomes.

- Identify how neighbourhoods, regions, and urban/rural location are associated with educational achievement and attainment.

- Summarize how different family structures are associated with educational outcomes.

- Define children in care and identify the reasons that such children may have educational disadvantages.

- Describe the educational outcomes of immigrant groups to Canada and define theories of assimilation.

- Summarize the educational barriers faced by undocumented immigrants.

- Explain what is meant by involuntary minority and how this concept relates to the educational outcomes of Aboriginals.

- Summarize how sexual orientation and heterosexism may impact on the education experiences of youth.

- Explain what is meant by special needs students and identify the major arguments in favour of inclusive education.

- Explain how early childhood interventions are meant to reduce inequality in educational outcomes.

- Describe how risk factors and protective factors are related to the concept of resilience.

Introduction

There are many characteristics of children and their families that have been found to be strongly associated with children’s educational achievement and, eventually, educational attainment. Educational achievement refers to how well a student does in school and is often assessed in terms of grades or scores on standardized tests, while educational attainment refers to the highest level of education an individual acquires, and is often assessed in terms of whether or not a person goes on to post-secondary education.

The previous chapters have highlighted some key areas where structural inequalities in educational outcomes can be expected. There are some key areas where structural inequalities in educational outcomes can be expected. For example, in Chapter 6, the process of socialization was discussed. An example is the process of socialization. How girls and boys are socialized differently from one another can impact upon their educational outcomes in terms of their confidence, performance, and interests. There are many factors that can impact on how well a child does in school and whether he or she pursues post-secondary education. Many of these different factors—but certainly not all—will be discussed in this chapter.

Many characteristics people have that can impact on the opportunities they have in life (or their life chances) can be divided into ascribed and achieved characteristics. Ascribed characteristics are those features of individuals with which they are born, such as race, sex, and the social class of one’s family. Achieved characteristics, in contrast, are earned or chosen through individual effort, like personal skills and occupational designations. Most life chances are influenced by a combination of ascribed and achieved characteristics. For example, earning a doctorate requires a lot of effort on the part of the individual, but people from middle- and upper-class families are more likely to pursue post-graduate degrees. In this chapter, however, the focus is on ascribed characteristics.

Gender

Gender was discussed in the previous chapter as is a major contributing factor to socialization. The outperformance of boys by girls on recent standardized reading tests was also discussed, which suggests that gender is no longer a barrier to educational achievement for girls—although debates have arisen as to whether the school environment has become feminized to match the learning styles of girls, leaving boys at a disadvantage (see Chapter 6).

In terms of educational attainment, in 2010, 71 percent of all women aged 25 to 44 had post-secondary education, compared to 64 percent of males in the same age range. Gender is not a barrier to access to post-secondary education in Canada. Women, however, are sharply underrepresented in the natural sciences, applied sciences, engineering, and mathematics (Canadian Council on Learning 2007b). In contrast, women are over-represented in education, health sciences, and social sciences. Women have entered the workforce in increasing numbers over the last several decades, and the vast majority of this increase has been in the “caring professions” such as nursing and teaching. The relative proportion of women in the scientific and technical occupations has declined in relation to the number of women who have entered the workforce.

Male-dominated professions in disciplines such as mathematics and engineering enjoy higher wages than the disciplines that females are more likely to choose. This difference contributes to the persistent wage gap that exists between men and women. Women earn about 68 percent of similarly qualified males. The wage growth of female-dominated professions is also remarkably slower than those dominated by males (Canadian Council on Learning 2007b).

Why don’t women pursue careers in the sciences? Standardized testing results do not reveal great differences between males and females in terms of their abilities in mathematics and science. Simpkins, Davis-Deane, and Eccles (2006), however, have found evidence of girls being less confident in their perceived ability in math and science skills than boys. Such findings suggest that environmental factors perpetuating gender stereotyping are more likely to be the causes behind career choices rather than innate biological and cognitive reasons.

Efforts are being made to encourage girls to pursue further education in the sciences, however. One such effort is by the Canadian Association for Girls in Science, a science club for girls between the ages of 7 and 16. Several chapters exist across Canada in order to stimulate girls’ interest and confidence in science. The club usually meets at the workplace of a guest scientist. The girls are given the opportunity to learn about the guest’s education and job.1

Social Class and Socioeconomic Status

There is a tendency in Canada to downplay the importance of social class, evident in the popular discourse that everyone is “middle class” and that the same opportunities are available to everyone—that it is just a matter of trying. There is much evidence to the contrary, however. Canada does not have an official “poverty line”—or a predetermined household income that a family must earn below in order to be considered “poor.” Rather, Statistics Canada has developed low income cut-offs (LICOs) which, in addition to income, take rural/urban location, region, and family size into account in their calculation. LICOs are not intended to be a poverty measure, but instead are an indicator of the threshold beyond which a family will devote a significant proportion of its income to the necessities of life, such as food and shelter, compared to other families. In 2008, 9 percent of people under the age of 18 lived in households identified by the LICOs.2

The socioeconomic status of a child’s family has been shown repeatedly to be one of the strongest indicators of a child’s educational outcomes (Gorard, Fitz, and Taylor 2001; Ma and Klinger 2000). Socioeconomic status refers to the income of a family, but also to other factors that determine how much income a family can make, such as level of education of parents and their occupations. Indeed, low socioeconomic status not only is associated with poor grades, but also is a strong predictor of dropping out of school and skipping school. Research has shown that an achievement gap exists between children from low-income families and other families. In other words, children from poor families tend to do less well at school.

Socioeconomic Status, School Readiness, and School Achievement

One reason that children from less advantaged families do worse at school is because they often lack school readiness. School readiness refers to a child’s developmental stage at which he or she is able to participate in and benefit from early learning experiences. The reasons that low-income children may lack school-readiness have been attributed to inconsistencies in parenting, repeated changes in their primary caregiver, their lack of role models, their greater likelihood of being unsupervised, and the lack of social support received by parents (Ferguson, Bovaird, and Mueller 2007). Multiple studies from Canada have shown that children from low-income homes have decreased school readiness (Brownell et al. 2006; Janus et al. 2007; Thomas 2006; Willms 2003).

Being under-prepared for early education means that such children are at a major disadvantage in the classroom. Lack of school readiness is associated with poor educational attainment. For example, in a Manitoba study, Roos et al. (2006) found that among all children whose families had collected social assistance payments in the last two years, only 12 percent passed a standardized writing test, compared to 89 percent of all other children. Analyses of Canadian longitudinal data have shown that socioeconomic factors are strongly—and persistently over the life course—associated with achievement in school (Hoddinott, Phipps, and Lethbridge 2002; Phipps and Lethbridge 2006; Ryan and Adams 1998). The relationship between low socioeconomic status and school achievement is by no means unique to Canada, however. The results from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) standardized tests discussed in Chapter 5 have demonstrated that in most countries, the socioeconomic status of families is a major factor in explaining the educational attainment of young people (Adams and Wu 2002).

Adult Educational Outcomes Associated with Low Socioeconomic Status of Family-of-Origin

The socioeconomic status of an individual’s family has been shown to impact on his or her overall educational attainment. In Chapter 2, theories of social mobility were presented that suggested various class-based reasons why such effects may occur. Theories of social mobility suggest various class-based reasons why such effects may occur. Statistics Canada data show that about 31 percent of youth from families in the lowest 25 percent of household income attended university, compared to just over 50 percent of youth from the highest 25 percent of household income (Frenette 2007). Other studies have found that socioeconomic status of families impacts the likelihood of youth going on to any form of post-secondary education (Finnie, Lascelles, and Sweetman 2005). It is possible that such youth, lacking the financial resources to pay for post-secondary education, find it difficult to secure loans to be able to attend, or find the negative aspects of carrying a large debt load to outweigh the potential benefits of going on with their education. Many may also have not had the influence in the home environment (i.e., emphasizing the benefits of further education) or have school performance (i.e., good enough grades) to make such choices possible (Usher 2005).

Neighbourhoods, Regions, and Location

Closely linked to socioeconomic status and social class are neighbourhood characteristics. Families with low socioeconomic status tend to live in areas with lower-cost housing. Sociologists and education researchers have recently become interested in how neighbourhood effects impact on school achievement and attainment. Living in areas with high concentrations of poverty is thought to negatively impact on children’s academic achievement, acting to keep children in cycles of poverty. Children in such neighbourhoods are more likely to have unemployed parents, low-quality schools staffed by discouraged teachers, and constrained social networks that do not give them much access to social contacts who reinforce the value of education (see the discussion of bridging social capital in Chapter 2). In other words, children living in such neighbourhoods may experience a lack of positive role models. Much research on neighbourhood effects has been based in the United States, however, where neighbourhoods characterized by high poverty are more numerous and have greater levels of crime and racial segregation (Oreopoulos 2008). Many low-income neighbourhoods in Canada are occupied temporarily by new immigrants who leave within five years. An overview of the research on neighbourhood effects on child outcomes in Canada suggests they may have somewhat of an effect on child educational attainment, but that the characteristics of the immediate family are likely to be of greater importance (Oreopoulous 2008).

Differences in standardized test scores by province were discussed in Chapter 5. Such discrepancies suggest that educational resources vary by what have come to be known as the “have” and “have not” provinces. “Have not” provinces are those that cannot cover the cost of their own federally mandated programs like social assistance, old age security, and employment insurance. Equalization or transfer payments are made from the federal government to the “have not” provinces in order for the province to be able to deliver services. For post-secondary education, the federal government does provide federal transfers to ensure high-quality education across the country. But because education from kindergarten to secondary school is under provincial jurisdiction, federal fiscal transfers are not received. Traditional “have” provinces such as Alberta, British Columbia, and Ontario have larger budgets to spend on education. This money does not itself ensure better performance by students, but financial resources allow better funding to create educational environments that are more conducive to student learning and success (Davies 1999). PISA results consistently show students from British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario to be at the top of the league tables for Canada (Knighton, Brochu, and Gluszynski 2010).

Additional research has shown that along with regional disparities, there are also marked differences between levels of educational outcomes between urban and rural areas (Desjardins 2011). In rural areas, compared to urban areas, high school dropout rates are significantly higher and PISA scores are significantly lower (Canadian Council on Learning 2006). Reasons for this disparity have been suggested to lie with the difficulty in attracting teachers to rural schools. While rural schools tend to be small and to offer more personalized attention to students, many are faced with staffing problems. Often, they can only attract younger, less experienced teachers who may be burdened with heavy workloads and teaching courses outside their area of expertise (Canadian Council on Learning 2006). Rural schools are also more likely to face difficulties attracting teachers who can teach specialty science courses, many of which are required for admission to post-secondary programs. Also, because economic conditions are often more difficult in rural areas, students (particularly males) are frequently forced to leave school to pursue employment to make up for deficits in their families’ incomes (Looker 2002).

Family Structure

As discussed in Chapter 6, families and schools are two of the main socializing agents of children. Before children enter school, the family is where children are socialized into particular ways of thinking about the world, including social and moral values and gender roles. When children enter school, a new force of socialization comes into play. The family, however, still remains an important part of a child’s socialization even after the child enters school.

The way that a child is socialized depends on many characteristics of the family. As discussed above, social class has been shown to be an important factor in the educational outcomes of children. Children who come from families with higher incomes and who have parents who are highly educated have a definite advantage in how well they perform in school and how far they will go with their education. There are many characteristics of families that can influence their children’s educational outcomes. As a primary socialization agent, the influence of the family is manifold.

One basic family characteristic that has been shown to impact on a variety of life outcomes (including education) is the structure of the family. According to census data from 2006, of all families with children in Canada, about 63 percent are in married couples (including stepfamilies), 11 percent are in common-law unions, and almost 26 percent are in lone-parent families. These figures have greatly changed over 25 years, as displayed in Figure 7.1. The number of married unions has decreased, with a resulting increase in common-law (unmarried and cohabiting unions) and lone-parent-headed households. The rate of marriage (with or without children) varies considerably across the country, with Quebec having the lowest rate, at 37.5 percent of adults in a marriage, while the highest rate is in Newfoundland and Labrador at 54.3 percent. The national average is around 48 percent of all adults (Vanier Institute of the Family 2010). In Quebec, over half of births occur within couples who are not married.

Figure 7.1 Family Structures of Families with Children

[h5p id=”7″]

Family structure is often examined in terms of the “two-parent biological parent” or “intact” model versus all others. Much research from Canada and elsewhere has shown that compared to “intact” family structures, children from other family forms tend to do less well at school and to have lower educational outcomes. Such research findings suggest that such family forms may have fewer resources available for children (social, cultural, and economic) and have fewer role models, and may also be characterized by higher levels of stress, all of which can adversely affect educational outcomes (Frederick and Boyd 1998; Garasky 1995; Hango and de Broucker 2007).

Divorce

Research has shown that experiencing the divorce of one’s parents can negatively impact on a child’s educational outcomes. In Canada, about 37 percent of marriages will end before the 30th anniversary (Ambert 2009). While there are no precise statistics available, it is estimated that between 20 and 30 percent of children born in the 2000s will experience the breakdown of their biological parents’ relationship.3 Strohschein, Roos, and Brownwell (2009) found in a Manitoba-based study that children who experienced a divorce of their biological parents before they were 18 were less likely to complete high school than children from intact families. Furthermore, younger children appeared to be more adversely affected than those who experienced a parental divorce in their adolescence. Other Canadian research (Evans, Kelley, and Wanner 2009; Martin, Mills, and Le Bourdais 2005) has also found that children of divorce often have lower educational levels. It should be noted that most children do not experience serious developmental or psychological problems as a result of divorce and that these lower educational outcomes do not apply to all children of divorce—they are just at a greater risk of having these outcomes than children from intact families (Corak 2001).

There are many potential reasons why some children of divorced parents tend to do less well than those from intact families. Such outcomes may be related to the lower levels of parental emotional support and supervision (and diminished parenting) available after a marital break-up. Others, particularly younger children, may not be able to cope with the emotional stress of the events. Also, going from a two-parent to a one-parent household is also often associated with a decrease in household income and therefore a decrease in a child’s standard of living. Going from an intact family to a one-parent family may constrain the quality of social, economic, and cultural capital (Chapter 2) available to children during their formative years (Corak 2001)—resources that have been found to be associated with later-life educational outcomes.

Lone-Parent Families

Much research has also demonstrated that children from single-mother families tend to do worse than children in intact families. There are two general pathways to single parenthood: (1) through marital dissolution, and (2) beginning as a single-parent. This is an important distinction to make, because single-parent households that are the result of marital dissolution are less likely to experience the persistent poverty that often characterizes never-married mother-headed households (Juby, Marcil-Gratton, and Le Bourdais 2005). In Canada in 2006, approximately 80 percent of lone-parent families were headed by females.4 Statistics Canada LICO rates for young people living in female lone-parent-headed households were 23.4 percent in 2008, compared to 6.5 percent of those living in two-parent families.5

Research has shown that children who grow up apart from their biological fathers tend to have lower school achievement, a higher tendency to drop out of school, and lower aspirations than children who are raised by both biological parents (Amato 2005; McLanahan and Sandefur 1994; Sigle-Rushton and McLanahan 2004). Canadian research has shown that compared to intact families, children from lone-parent families are more likely to drop out of high school and not pursue post-secondary education (Hango and de Broucker 2007). See Box 7.1 for a discussion of teen mothers and their children.

Box 7.1 – Teen Moms and Their Children

Teenage mothers have been a topic of considerable recent interest—particularly from the media. These mothers are characterized by having a birth during their teenage years and usually as being single parents. Studies have shown that teenage mothers tend to have low educational attainment and lower household incomes (Hobcraft and Kiernan 2001; Hofferth 1987; Hofferth, Reid, and Mott 2001; Robson and Berthoud 2003). Studies that have examined the children of teenage mothers have also noted that these children are at a higher risk for a range of adverse outcomes, including poorer cognitive development (Moore, Morrison, and Greene 1997), poorer health (Botting, Rosato, and Wood 1998; Peckham 1993; Wolfe and Perozek 1997), and worse educational outcomes (Jaffee, Moffit, Belsky, and Silva 2001; Moore et al. 1997).

In 2008, the average rate of teen births was 12 per 1000 teenage females in Canada. The rate varied considerably by province, from almost 95 in Nunavut to 8.5 in Quebec.6 In contrast, the average mother’s age at birth in Canada was 29.4 years. Canadian research has shown that, in terms of educational outcomes, the children of teenage mothers have a higher risk of not graduating from high school (Brownwell et al. 2010; Jutte et al. 2010) and poor performance in school (Dahinten, Shapka, and Willms 2007). The authors also found that children of teenage mothers were more likely to become teenage mothers themselves, be on social assistance in adulthood, and have experienced intervention by child protective services during their childhoods.

Many teen mothers have disadvantages that can be traced back to the socioeconomic status of their families of origin (Robson and Pevalin 2007). This cycle of economic disadvantage is often passed on to their offspring, as a teenage girl who becomes pregnant is unlikely to complete high school. Some high schools in Canada, however, have put supports in place especially for teenage mothers. The Louise Dean School in Calgary is a school for pregnant and parenting teenagers that has been operating as such for over 40 years. The school offers a wide range of supports for pregnant and parenting teens to allow them to complete secondary school and also to support and educate them in raising their children. They also offer help to access other supports—such as with career development and financial assistance. According to the school’s website:

‘[t]he school currently operates with a September to June traditional program along with a five week summer school component. There are multiple start points for students throughout the year to ensure ongoing accessibility for all students. Most of the students are residents of Calgary, although students throughout Alberta and other provinces also attend. The school is unique due to the ongoing and onsite collaboration with Catholic Family Service (social worker support), onsite childcare (Learning Centre), and Alberta Health Services. Students are really offered ‘wrap around’ support to assist them with education, housing, counselling and childcare support.

To support the young women while they are at Louise Dean Centre, a team consisting of an educator, a social worker, an early childhood educator, and a health professional works with them to improve academic achievement, social/emotional concerns, and healthy lifestyle choices for themselves and their babies. The team also accesses other supports as needed such as medical care, career development, and financial assistance.

Catholic Family Service provides counseling for the students and facilitates groups for parenting teens, teen fathers, grandparents, and young women considering adoption. In addition to counseling, Catholic Family Services provides the on-site licensed daycare facility, the Dr. Clara Christie Infant Learning Centre, which operates during the school week to provide care for infants under the age of eighteen months. The Centre is licensed for 40 babies. Trained staff also assist the young mothers with parenting skills and offer regular workshops on topics of interest to the students.”7

In a study of the life outcomes of former students of the Louise Dean School, researchers (Simpson and Charles 2008) found that students of this school tended to do better than the average teenage parent in terms of educational attainment and employment.

Source: Used with permission of the Calgary Board of Education and Catholic Family Service at Louise Dean School.

Stepfamilies

Stepfamilies include both married and unmarried (common-law) unions in Canada, with about half of stepfamilies in Canada being the result of remarriages (Ambert 2009). When a parent re-partners, it is indeed easy to imagine the great deal of adjustment that must be made by the child, which can be difficult, particularly if the child does not like the new partner. About 10 percent of Canadian children under 12 are living in a stepfamily (Ambert 2009). About 46 percent of stepfamilies have children of both adults, 43 percent contain the female’s children only, and 11 percent contain the male’s children only (Vanier Institute of the Family 2010). The addition of a stepparent can also mean the addition of stepsiblings to a household, resulting in blended families—which, according the figures above, is the case the majority of the time in such families.

The research on the effects of living in stepfamilies on children’s outcomes has rather mixed results (Ambert 2009). Remarriage often has the effect of raising the total household income of a parent, which can have positive effects on the socioeconomic status of a family (Morrison and Ritualo 2000). The age of a child when a parent remarries also appears to be an important factor in how well the child adjusts, with younger children being more likely to be supportive of the presence of a new parental figure (Bzostek 2008). If the new parent is accepted by the child and a bond forms, the presence of a stepparent can enhance the outcomes of a child, but if the child is hostile to the stepparent or abuse occurs the outcomes are obviously less favourable (Kirby 2006).

Research has also found that older adolescents are more likely to leave home earlier if their custodial parent remarries. Similarly, adolescents from stepfamilies have been found to delay their pursuit of post-secondary education (Hango and de Broucker 2007). And leaving home at an early age has the effect of lessening the likelihood that a young person will pursue post-secondary education at all (Boyd and Norris 1995). Canadian research has also found that children living in stepfamilies (as well as those raised by lone parents) are more likely to display hyperactivity (Kerr 2004; Kerr and Michalski 2007).

Same-Sex Parents

Same-sex marriage was legalized across Canada in 2005. Legal rights are also extended to common-law same-sex unions the same way that they are to common-law opposite-sex unions in Canada. The 2006 census indicated that there were about 45 000 same-sex couples living in Canada, of which almost 17 percent were married. Of these couples, 9 percent had children under the age of 24 living in the household. Lesbian couples were far more likely to report having resident children (16 percent) than gay male couples (3 percent).8

A Canadian governmental report commissioned by the Department of Justice (Hastings 2006) examined the findings of about 100 studies from around the world on the outcomes of children who were raised in various family structures, including same-sex parents. The report concluded that children raised by same-sex female parents had the same emotional and behavioural development as those living in “traditional” families. The findings were limited to female same-sex parents because of the lack of research on male same-sex parents.

In terms of educational outcomes, American researchers have found no difference in school achievement (Wainright, Russell, and Patterson 2004) and progress through school (Rosenfeld 2010) between children raised by same-sex and opposite-sex parents. No Canadian research on the educational outcomes of children raised by same-sex parents currently exists.

Children in Care

The term child in care refers to a minor who has been removed from his or her family by provincial child protective services. There is no national definition of a child in care because child welfare services are under provincial/territorial jurisdiction in Canada. In all cases, however, the provincial or territorial jurisdiction has removed a child from his or her home at least temporarily and has assumed responsibility for the minor. The reasons for removal usually pertain to neglect and maltreatment, with many having experienced physical, emotional, or sexual abuse. Children in care are also known as foster children, Crown wards (wards of the state), youth in care, or children in “out-of-home care.” Regardless of the term used, such children have experienced at least part of their childhood—and often the vast majority of it—being raised in foster families. Mitic and Rimer (2002) report that in British Columbia in 2001, for example, 10 000 children were in care at any one point in time, with half being in temporary care (i.e., returning to their families within six months) and the other half being in continuing custody. On the extreme end of the spectrum are children who are raised in “secure units,” which are highly supervised residential settings where children who are deemed to be a significant risk to themselves or others are placed.

Mulcahy and Trocmé (2010) report that in 2007, there were an estimated 67 000 children in care across Canada on any given day. This translates into a rate of just over 9 children in care per 1000. This number has steadily risen since the 1990s.

Children brought into care often come from families on social assistance and headed by a lone female parent (Mitic and Rimer 2002). Related research has found that a disproportionate number of children in care are Aboriginal. In 2007, about 27 000 Aboriginal minors were in out-of-home care. They comprise approximately 40 percent of the total in-care population. Within their age groups, however, they comprise only 5 percent of the total Canadian population (Gough, Trocmé, Brown, Knoke, and Blackstock 2005).

The handful of studies that have examined children in care and educational outcomes have found that these children face significantly more challenges in achieving basic literacy than other children. A review by Snow (2009), examining the educational supports and educational attainments of children in care in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom, found that there are numerous barriers facing these children. Children in care often suffered from poverty, abuse, neglect, and malnutrition before “detection” by the state. Malnutrition affects developmental progress in children and can hamper proper growth of the brain. Abuse and maltreatment can also compromise a child’s emotional and cognitive development. Such children are at a higher risk of conduct disorders and are more likely to have to repeat grades. Numerous studies have also found that children in care are many times more likely to be in need of special education, compared to the general population (Flynn and Biro 1998; Janus and Offord 2007; Scherr 2007; Turpel-Laford and Kendall 2007).

Therefore, children enter care situations having experienced a range of abuse and maltreatment. Early experiences can impair learning and educational attainment throughout childhood and into adulthood. While placement into care is deemed necessary and oriented toward protecting children, much foster care is associated with multiple placements and separation from siblings (Snow 2009). Getting moved from placement to placement creates an unstable life for many children in care and is associated with behavioural problems in children.

Emotional challenges are also faced by children in care. The experience of leaving one’s family and being placed in care can result in low self-esteem and feelings of abandonment (Mitic and Rimer 2002). Even among children who are not in care, residential mobility (i.e., moving) has been found to be negatively associated with academic achievement (Pribesh and Downey 1999; Rumberger and Larson 1998). Moving from placement to placement further disrupts a child’s social circle and educational continuity. Cultural fragmentation and isolation may also be experienced by Aboriginal children in care if they are not connected to their culture during a placement (Mitic and Rimer 2002). Children in care also have significantly higher school absenteeism, grade repetition, lower scores on standardized tests, and lower graduation rates (Mitic and Rimer 2002; Snow 2009). These disadvantages often carry over into adulthood, with former children in care being disproportionately represented among the homeless, imprisoned, and social assistance populations (Snow 2009).

Programs Targeted at Children in Care

The previous research identified above has highlighted the problems faced by children in care. As a result, suggestions for enhancing and maximizing the opportunities for these children have been made by researchers and policy-makers. Moffat and Vincent (2009) have suggested that early interventions (between the ages of 1 and 4) with literacy-promoting activities for the in-care population within their foster placements is a start to narrowing the achievement gap. To further test whether educational interventions can help young people in foster care, Flynn et al. (2011) used an experimental design consisting of 77 children in care in Ontario, randomly assigning them to one of two groups. The first group received tutoring by the foster parent, while the second did not.9 Foster parents in the first group were trained in a six-hour workshop to use instructional training materials in order to tutor their foster child. The foster parents in the first group agreed to provide three hours of tutoring to their foster child for 30 consecutive weeks and were required to send data on the child’s performance to the research team on a weekly basis. The researchers found that students who had received the tutoring made much larger gains in the school year compared to those who did not, suggesting that the tutoring was effective. These findings suggest that such interventions can reduce the achievement gap between children in care and other students.

Mitic and Rimer (2002) have argued that a major missing piece in the pathways of children in care to educational success is the communication between child welfare agencies and schools. Of primary importance is also the limiting of relocation of children to maximize stability for children in care. The authors note that school may be the most consistent and stable aspect of a child in care’s life, particularly when the certainty of their home life is unclear. Where moves are necessary, policy-makers suggest that provisions are put into place to make the transition as smooth as possible.

Teachers are also important sources of guidance to children in care. Mitic and Rimer (2002) argue that to best help children in care, their teachers need to be kept informed about their living situations. Similarly, teachers need to be trained about how to be sensitized to the unique needs of this population. Mitic and Rimer (2002) argue that clear lines of communication and co-operation among social workers, foster parents, and schools are needed to enhance the school performance of children in care.

Immigrants and Visible Minorities

In addition to Canada’s Aboriginal groups, the population of Canada is also made up of many groups of immigrants. Canada has a lengthy history of being a major immigrant-receiving nation. Small amounts of immigration to New France (now Quebec) from France began in the 1600s, while the British began to immigrate to Upper Canada (now Ontario) in the late 1700s. More settlers, particularly from Britain and Ireland, arrived in Canada after the War of 1812. Settlers of varied European origin arrived prior to the First World War, settling in areas beyond Quebec and Ontario, most notably the Prairies. A large wave of immigration from these European groups also occurred in the late 1950s, including large numbers from the Ukraine and Russia. Since the 1970s, however, immigration to Canada has largely been comprised of visible minorities from developing countries. According to Statistics Canada, Canada admitted 252 179 immigrants in 2009.10 The largest groups were from China (11.5 percent), the Philippines (10.8 percent), and India (10.3 percent). The next largest groups were Americans (3.8 percent), British (3.8 percent), and French (2.9 percent).

Canada has the highest immigration rate in the world and this is expected to continue partly due to the low fertility rates in Canada. The main reasons that people immigrate to Canada are to be reunited with family members who already live here, humanitarian reasons (i.e., refugees fleeing dangerous situations in their countries of origin), and economic migration (highly skilled immigrants that are deemed to contribute to Canada’s workforce and economy).

There are many generations of immigrants in Canada. First generation immigrants are those who were born outside the country. The term second generation immigrant refers to someone who was born in Canada, but has at least one parent who was born outside of Canada (Kučera 2008). Technically, this popular term is incorrect; those deemed second generation immigrants are not actually immigrants because they were born in Canada. Sometimes researchers use the term 1.5 generation immigrant, which refers to those who immigrated to Canada when they were children (Kobayashi 2008) and had a substantial amount of their early schooling occurred while living in Canada. While not born here, a significant amount of their childhood was spent in Canada. Individuals with parents born in Canada are referred to as third-or-higher generation immigrants. In addition to immigrant status and generation, people also are distinguished by whether or not they are members of a visible minority. Visible minorities are groups of people who are visibly not of the same race as the “majority” of people in a country.11

Immigrants and Theories of Assimilation

There are two major approaches to understanding how immigrants integrate into their host society. The traditional approach of assimilation theory is that the adaptation of immigrants follows a linear trajectory. This model assumes that there is a fairly straightforward relationship between how long an immigrant group spends in the host country and the level of adaptation of its members—both within and between generations. This “straight-line approach” suggests, for example, that children who are young when they arrive in Canada will have more favourable academic outcomes than those who arrive at older ages. Additionally, successive generations should outperform their predecessors—second generation immigrants should do better than the first generation, and third generation immigrants should do better than the second generation (Anisef et al. 2010). An alternative theoretical approach called segmented assimilation theory differs from the linear trajectory approach because it assumes that different immigrant groups will have different paths to assimilation (Portes and Zhou 1993). The segmented assimilation approach emphasizes that some immigrant groups may experience downward mobility, experiencing poverty, while others may experience varying upward and downward mobility for each successive generation. Other groups may, in fact, follow the “straight line” trajectory suggested by the traditional approach, and the longer they are represented in the host society, the more their success may mimic the experiences of the White middle class.

Educational Achievements of Immigrant Groups

Standardized tests that are administered to some Canadian students were discussed in the previous chapter. Researchers have used these data sources to examine how immigrant children perform on a variety of educational outcomes compared to native-born children. For example, using data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Ma (2003) found that children born outside of Canada did worse on reading and science components of the test, compared to non-immigrant children. There were no differences, however, between the two groups of students on mathematics test scores.

Gluszynski and Dhawan-Biswal (2008) also examined the PISA data, but looked at those born outside Canada and first generation immigrants in more detail. Both foreign-born and first generation immigrant children performed worse in reading than those who were native-born with at least one Canadian-born parent. They found that this difference was even more pronounced for those who had been in Canada for less than five years and who spoke a different language at home than the test language (English or French). Immigrant boys also tended to do worse than immigrant girls. Gluszynski and Dhawan-Biswal (2008) also found that the longer an immigrant family had been in the country, the better the student did, indicating that the achievement score between immigrants and native-borns narrowed relatively quickly, suggesting rapid integration. Using the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) also discussed in Chapter 5, Sweetman (2010) compared immigrant children’s test scores to those of native-born children. Years in the school system narrowed the gap between immigrants and native-born, also suggesting that the longer a child has been in the school system in the host country, the more similar his or her performance is to that of a native-born child.

Language proficiency is another factor in how well children of immigrants—particularly young children—achieve at school. Worswick (2001) analyzed the school performance of children of first and second generation immigrants. In early school years (Grades 2 through 5), immigrant children whose parents’ first language was not the language of instruction at school were disadvantaged in terms of vocabulary and reading. However, evidence of rapid assimilation was found as by age 13, with these children performing at the same—or better—levels than their counterparts with Canadian-born parents. Further work by Worswick (2004) found that immigrant children whose parents’ mother tongue was not English or French had lower vocabulary scores than those with Canadian-born parents, although their reading and mathematics scores were no different. Thus, having neither parent speak English or French as a first language appears to account for much of the difference observed between immigrant children and their Canadian-born peers, at least in early schooling. Young children who enter school with little or no proficiency in either English or French have time to catch up, but similar adolescents entering school will be at a significant disadvantage because they have a very short time to become fluent in order to succeed in secondary school (Gunderson 2007).

Potential Reasons for Differences in Educational Outcomes between Immigrant Generations and the Native-Born

There are several reasons why immigrant children may face disadvantages related to their education. Rousseau and Drapeau (2000) found that traumas experienced in the homeland (due to war) before immigration, combined with cultural uprooting, can lead to emotional problems among refugees, which can in turn hinder educational achievement in refugee children. Their study involved looking at the scholastic achievement of immigrants from Cambodia and Central America who were attending six Montreal-area schools.

Many immigrants, however, do not arrive in Canada as refugees, and therefore other explanations for potential differences in their educational performance compared to native-borns must be examined. The role of socioeconomic status and social mobility were described above. These factors apply to immigrants as well—and many new immigrants live in impoverished communities and have below-average household incomes. Thiessen (2009) has shown that when socioeconomic characteristics of the family are taken into consideration, the gap between students of African and Latin American origin and native-born European Canadians narrows considerably. These findings suggest that much of the disadvantage experienced by some immigrant and Canadian-born ethnic groups is largely attributable to economic factors.

As noted in Chapter 6, students from disadvantaged backgrounds and racial minority students are more likely to be “streamed” into low-ability tracks or streams. While existing literature has found streaming had tended to place immigrants and visible minorities in higher ability streams (Krahn and Taylor 2007), many differences by origin group were noted. Specifically, those who had arrived to Canada during adolescence and those with poor official-language proficiency were more likely to be streamed into the lower ability groups.

Socio-cultural context must also be taken into consideration, such as the cultural definitions of success that characterize an ethnic group (Leung 2001). Some researchers argue that part of the answer to why different immigrant groups perform differently in school outcomes lies in the culturally specific expectations that exist within ethnic groups. Ethnic capital (Borjas 1992) refers to the overall educational and income levels of particular ethnic groups, which are thought to be able to enhance life outcomes of children of immigrants. For example, Chinese immigrants have very high levels of educational attainment, and this group characteristic may contribute to the performance of individual second-generation Chinese immigrants. Borjas (2000) argues that growing up in a culture in which high achievement is displayed as the norm of those in close social proximity makes individuals internalize such goals for themselves. In a study of the educational attainments of children of immigrants, Abada, Hou, and Ram (2008) found that children of Chinese, Indian, African, and West/Asian and Middle Eastern parents had higher ethnic capital. Differences in ethnic capital, however, explain only a part of the gap between the outcomes of different second generation ethnic groups.

Related to the idea of ethnic capital is the notion that children from particular ethnic backgrounds, particularly those of Asian descent, are strongly encouraged to pursue post-secondary education, especially university (Chow 2004; Finnie and Mueller 2010). Suárez-Orozco and Suárez-Orozco (2001) propose that the optimism of immigrant parents, particularly those who may have experienced disappointment at their own inability to succeed in their host country, may “will ambition” (p. 105) to their own children. Due to their own perceived post-immigration decline in status, they may push their children to succeed even more. Specifically, Chow (2004:321, citing Peng and Wright 1994) argues that “various characteristics of Asian culture such as docility, industriousness, respect for authority, and emphasis on learning are highly compatible with those required for academic success.” A summary of the possible reasons that explain the differences between immigrant and non-immigrant in terms of educational achievement is provided in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1 Potential Reasons for Educational Outcome Differences between Immigrants and Non-Immigrants

[h5p id=”8″]

Anisef et al. (2010) also found that a student’s place of origin was a strong predictor of whether or not a first generation student would drop out of high school, which supports the segmented assimilation hypothesis. The study was based on data from a Toronto cohort of Grade 9 students that was studied over a six-year period. Specifically, individuals born in the Caribbean were much more likely to drop out of school compared to native-born students. In contrast, this risk was much smaller among students who originated from Southern Asia, Eastern Asia, and Europe. Anisef et al. (2010) argue that much of the difference between those originating from the Caribbean and other groups can be better explained by the characteristics of the neighbourhoods in which youth are living, with many living in economically deprived areas—areas that tend to have cheaper housing and thus attract new immigrant groups. Canadian research has shown that neighbourhood poverty and schools that have a high proportion of students from low socioeconomic backgrounds contribute to student dropout rates in Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal (McAndrew et al. 2009). Recent attention to the poor academic outcomes of Black youth, particularly in Toronto, have motivated the creation of an Africentric public school, which was discussed in Chapter 6. The curriculum of this school is modified to be more relevant to the lived experiences of Black students, with the intention of reducing the dropout rates among this population.

Other works by Anisef and associates (Anisef and Kilbride 2003) have found that first generation Caribbean youth often find themselves socially isolated, which is associated with their becoming frustrated and falling behind in school. As social capital theory points out (Chapter 2), the types of relationships and networks that individuals have contribute to their educational outcomes and later-life successes. Young people who live in poverty and experience social isolation will have compromised social capital because their bridging capital (the linkages between groups) will often be weak. Bridging capital is what would give youth access to the mainstream and opportunities not available in their immediate group. While they may have strong bonding capital (within their own ethnic group), this may not be enough to foster academic achievement. According to Anisef et al. (2010), because “residential segregation favors bonding over bridging [capital], immigrant youth who live in and attend schools in poor neighborhoods and ethnic enclaves are more likely to network or bond with peers of similar social, cultural and economic backgrounds. Opportunities for immigrant students to accrue bridging capital may therefore be limited, thereby increasing the probability of poor academic performance and leaving school early without graduating” (p. 108).

Another characteristic that may partially explain the achievement differences between immigrants and Canadian-born children is their own and their parents’ aspirations for their education. Research by Krahn and Taylor (2005) has found that visible minority youth in Canada have high aspirations toward post-secondary education. In fact, their aspirations are, in general, higher than those of Canadian-born not-visible-minority youth. Others have found that first generation immigrant parents have higher educational expectations of their children compared to those parents who were born in the country (Glick and White 2004; Smith, Schneider, and Ruck 2005). The heightened expectations of these groups may act as a “buffer” against economic disadvantages experienced by a family that may otherwise lessen the educational success of their children (Sweet et al. 2010).

Post-Secondary Educational Outcomes of Immigrants

Much recent research has shown that second generation immigrants to Canada have comparable (Worswick 2004) and often higher educational attainment than their peers who have domestic-born parents (Aydemir, Chen, and Corak 2005; Kučera 2008; Palameta 2007; Picot and Hou 2011). Boyd (2002) has shown that 1.5 generation and second generation immigrants in Canada have a strikingly different pattern of educational outcomes than in the United States. In Canada, their achievements often exceed those with domestically born parents, while in the United States, this same class of immigrants tends to lag behind their peers.

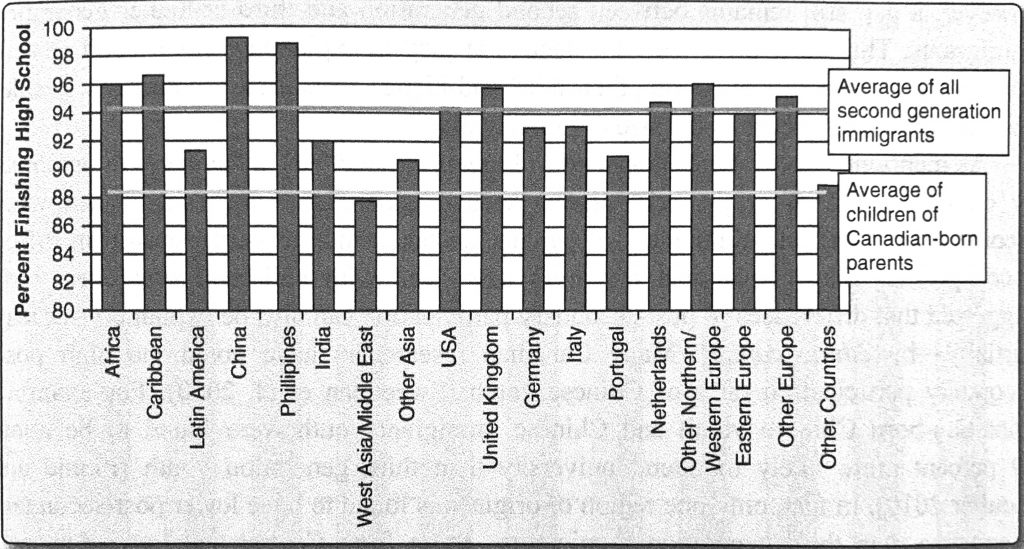

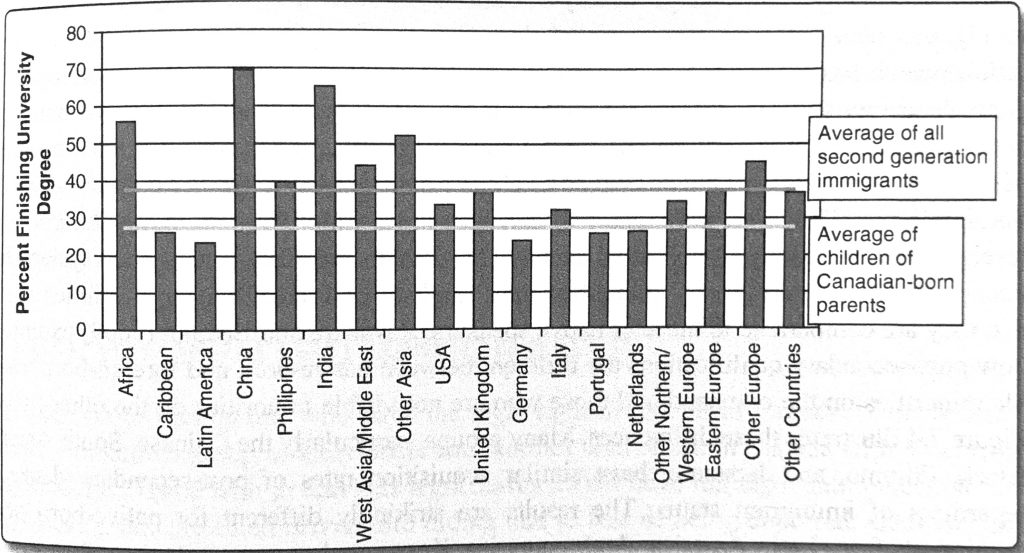

Much variation, however, exists when the educational outcomes of specific groups of second generation immigrants are examined (Boyd 2008; Rothon, Heath, and Lessard-Phillips 2009). For example, second generation children of immigrants from China, India, Pakistan, and Africa have been found to outperform children with native-born parents (Rothon et al. 2009). In fact, the researchers found that the educational accomplishments of all second generation groups were superior to the majority population with Canadian-born parents. The authors note that a similar pattern exists among second generation immigrants in the United Kingdom, but that in the United States, Black Caribbean and Mexican immigrant groups tend to lag well behind the majority population. Other recent evidence of the educational attainment among adult second generation immigrants by Statistics Canada shows that this group, regardless of parents’ country of origin, are more likely to finish high school than those with Canadian-born parents (see Figure 7.2). As well, compared to their counterparts with Canadian-born parents, many of these groups are significantly more likely to earn a university degree (see Figure 7.3).

Findings such as these naturally raise questions about why second generation immigrants appear to outperform those with native-born parents. The educational attainment of second generation immigrants, particularly visible minorities, has consistently been found to be higher than third-or-higher generations (Abada, Hou, and Ram 2008; Aydemir and Sweetman 2007; Bonikowska 2008; Boyd 2002; Finnie and Mueller 2010). As discussed above, studies in social mobility have demonstrated that the socioeconomic status of parents is highly predictive of their children’s educational attainment; those whose parents who have post-secondary education are more likely to themselves obtain such credentials. In the second generation immigrant population, however, this relationship is much weaker. Low credentials of parents are much less of an impediment to post-secondary educational attainment for second generation immigrants than for those with native-born parents (Bonikowska 2008; Picot and Hou 2011). Aydemir, Chen, and Corak (2008) found that among second-generation immigrants, the strength of the association between parental education and child education was one-third of what it was among those with Canadian-born parents. Similarly, income is also only a weak predictor of the success of second generation immigrants.

Source: Statistics Canada, Ethnic Diversity Survey, Adapted from www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11f0019m/2008308/t-c-g/tbl1-eng.htm

Source: Statistics Canada, Ethnic Diversity Survey, Adapted from www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11f0019m/2008308/t-c-g/tbl1-eng.htm

Another factor that at least in part explains the achievements of the second generation immigrants is that they are much more likely to live in large urban areas (Bonikowska 2008). Also discussed above, living in large urban areas tends to be associated with higher educational attainment. Even after taking urban dwelling into account, however, a gap still remains between second generation and third-or-higher generation immigrants. Therefore, there are other factors at play in explaining why second generation immigrants are outperforming their third-and-higher generation counterparts, besides parental education, income, and size of municipality.

As mentioned above (and illustrated in Figures 7.2 and 7.3), differences in outcomes by country/region of origin exist among second generation immigrants. Even when income and educational attainment of parents are taken into account, significant differences persist. Like educational outcomes associated with children, researchers have suggested that differences in post-secondary participation can also be explained—at least partially—by ethnic capital. Many Canadian researchers have noted the high post-secondary participation rates of Chinese youth (Sweetman et al. 2010). For example, Canadian-born Chinese youth and Chinese immigrant youth were found to be about 50 percent more likely to attend university than third generation youth (Finnie and Meuller 2010). In fact, only one region of origin was found to have lower post-secondary attendance than third generation immigrants—those from Central and Latin America. Abada and Tenkorang (2009) have also found that that the type of post-secondary institution attended by those with immigrant parents also varies according to ethnic origins. Chinese and South Asians (Indians, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis) were far more likely to attend university compared to Whites and Blacks, but Blacks were more likely than other groups to complete vocational programs or attend college.

Such differences by country/region of origin by second generation immigrants spark the additional question of whether ethnic capital is dependent on the generation of immigrant. In other words, do visible minorities possess different stocks of ethnic capital that change depending on their length of stay in Canada? For example, do foreign-born Chinese immigrants have different ethnic capital than Chinese-Canadians born in Canada? Very little research has been done on this specific topic in Canada. Boyd (2002) found that, in general, second and 1.5 generation visible minority immigrants had superior outcomes to both third generation visible and non-visible minority groups. The finding that the outcomes of the 1.5 generation (those who arrived as children) are similar to those of second generation immigrants is largely attributable to language acquisition. Even if young children are foreign-born, spending a substantial amount of time in the Canadian school system as young children would greatly strengthen their English- or French-language abilities such that they are comparable to those of native speakers. Ravanera and Beaujot (2009) examine how post-secondary qualifications are different between native-born and foreign-born visible minorities on the one hand and those who are not visible minorities on the other hand. Figure 7.4 illustrates these differences. Many groups, particularly the Chinese, South Asian, Black, Filipino, and Japanese, have similar acquisition rates of post-secondary degrees regardless of immigrant status. The results are strikingly different for native-born and immigrants from Latin America, Arab countries, Korea, and to some extent southeast and west Asia. The higher acquisition rates of post-secondary degrees among Latin American and Arab immigrants can perhaps partly be explained by Canadian immigration policies.

Figure 7.4 Proportion of Population Aged 15–24 with University or College Degree by Visible Minority and College or University Degree by Ethnic Origin and Whether Native-Born or Immigrant

| Country of Origin | Native Born | Immigrant |

| Chinese | 18% | 23% |

| South Asian | 18% | 18% |

| Black | 14% | 13.5% |

| Filipino | 16.5% | 15% |

| Latin American | 9.5% | 16% |

| Southeast Asian | 14.5% | 17.5% |

| Arab | 18% | 24% |

| West Asian | 13.5% | 16.5% |

| Korean | 20% | 15% |

| Japanese | 17% | 18.5% |

| Not Visible Minority | 17% | 20% |

Many immigrants arrive in Canada as skilled workers and professionals who must achieve a number of “points” in order to have a qualifying application for immigration. Educational attainment is one major area in which points are awarded, as are language skills and occupation.12 This figure suggests that there is some evidence that ethnic capital is fairly consistent among ethnicities for many groups, regardless of location of birth (i.e., Canada or elsewhere) particularly among the Chinese, South Asian, Black, Filipino, and Japanese.

Undocumented Immigrants

In addition to immigrants who have the legal right to remain in Canada, there is also a largely unknown group of individuals and families who reside in Canada with precarious legal status. Those with precarious legal status do not have full legal entitlements to live in Canada, and are often driven into hiding due to fear of being deported. Because such people live with the fear of being deported, there is not much research done on this population as they are largely hidden in our society. There are several routes to experiencing precarious status. This group includes those who are on temporary work permits, those who have overstayed their visas, those awaiting outcomes of refugee claims, and those awaiting the outcomes of applications to Humanitarian and Compassionate applications (or appeals). The latter is an application for permanent residency for individuals who would face “excessive hardship” if they were to return to their home countries.13 Some with failed applications may have received deportation orders on which they did not act.

There are two major issues facing children of parents with precarious status when it comes to education: (1) the ability to be able to enrol in school at all, and (2) the fear of being caught by immigration officials because one is enrolled in school. It should be noted from the outset that examples discussed will focus on Ontario—not because there are not undocumented immigrants in other parts of the country, but because the entire body of research that exists on such matters in Canada comes from Ontario. As a major destination for immigrants and as one of the most multicultural cities in the world, it is therefore not surprising that a bulk of Canadian instances on undocumented immigrant children and education would emerge from Toronto.

Advocates for undocumented children point to the international legal rights for children which guarantee all access to education, and which are upheld in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.14 Advocates for children of adults with precarious legal status argue that Canada, as a signatory to this convention, is legally required to provide access to education for these children regardless of their (or their parents’) legal status. As noted by Bernhard et al. (2007), the UN Convention stipulates that in decisions that affect children, the interests that most favour the child must be placed front and centre.

Critics also point to Ontario’s Education Act, particularly Section 49.1, which explicitly states that a person “shall not be refused admission because the person or the person’s parent or guardian is unlawfully in Canada.”15 Regardless of this wording of the Education Act, many undocumented immigrants report their children being denied access to school because of the demands of administrators for documents that the parents simply cannot provide, such as evidence of application for immigration (Koehl 2007; Sidhu 2008). Thus, while children are deemed entitled to education through international and provincial law regardless of immigration status, there has been considerable evidence that these laws are not always upheld.

Even when children are granted access to education, many attend with a certain degree of fear of their status being revealed. In the spring of 2006, much media attention was given to cases of the Canadian Border Service agents entering Toronto schools and demanding that certain children be brought to the principal’s office. The children were part of families who had been denied refugee status and failed to be present for their deportation flight back to their country of origin. Canada Border Services agents held the children until the parents turned themselves in. When parents arrived, they were taken into custody and placed in a detention centre.16 Unsurprisingly, the case attracted much negative publicity (Koehl 2007), which eventually resulted in the federal department apologizing and stating that this was atypical practice for the Canadian Border Services Agency.The threat of being found out, and the requirements of many schools to provide official citizenship or immigration documents in order to become enrolled in school, mean that a large proportion of children of adults with precarious status are not in school. As a result of the incidents above, the Toronto District School Board unanimously passed an “Access Without Fear: Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy for children who do not have legal immigration status in May of 2007.17 Under this policy, children and their families are not required to reveal their legal status to schools and schools agree not to pass on any information to Canadian Immigration authorities.

Aboriginals

The history of Aboriginal people with Canada’s education system—particularly residential schooling—was discussed in Chapter 3. Much Canadian research has shown that educational outcomes for Aboriginal youth are poor (Aman and Ungerleider 2008; Aydemir, Chen, and Corak 2008; Brunnen 2003; Finnie, Lascelles, and Sweetman 2005; Krahn and Hudson 2006; Thiessen 2009).

Ogbu (1992) has distinguished between two types of minorities: voluntary and involuntary. Immigrants are voluntary minorities because they usually immigrate to the host country with the intention of starting a better life or giving their children greater opportunities. Involuntary minorities are those who are minorities due to historical circumstances that they could not escape under which they were conquered and enslaved. Aboriginal people in Canada can be considered involuntary minorities in the sense that they were subjected to rule by colonial settlers. Specifically in the case of education, these involuntary minorities’ children were also forced into the residential schooling system (Thiessen 2009)—the purpose of which was to socialize them into British ways of living (and de-socialize them out of their Aboriginal culture). Because of these historical experiences, Aboriginals (and involuntary minorities in general) may be disconnected from the education system given its historical role in stripping children of their culture. Using Ogbu’s theoretical perspective, the superior academic performance of voluntary minorities (described in the previous section on immigrants) can be attributed to their ability as voluntary minorities to maintain a positive attitude toward the Canadian education system (Samuel, Krugly-Smolska, and Warren 2001).18

Directly related to the conditions of being involuntary minorities, other researchers have suggested that the poor educational performance of Aboriginals can be traced to several other root causes. As discussed in Chapter 5, many curricular practices are based on Western European models of learning, which do not take Aboriginal knowledge and “ways of knowing” into account (Aikenhead 2006). There is often a large divide between what Aboriginal children have been taught about their culture and traditions in the home and the content of curriculum that is taught in schools. Failure to integrate curricular materials that are relevant to Aboriginal cultures is argued to be symptomatic of persistent colonial educational practices (Pirbhai-Illich 2010) that perpetuate an internalized colonial ideology of Aboriginal cultural inferiority. The absence of culturally relevant curriculum, combined with the low expectations that teachers tend to have for Aboriginal students (Riley and Ungerleider 2008), have been argued as two significant disadvantages that Aboriginal children face before they even begin school.

In terms of academic achievement, the scores of Aboriginal students on standardized tests have been found to be consistently lower than those of other students (Ma and Klinger 2000; Richards, Vining, and Weimer 2010). British Columbia is the only Canadian province that publishes the results of standardized tests by various school and student characteristics, including “Aboriginal identity” (Aman 2009; Richards, Vining, and Weimer 2010). As discussed in Chapter 5, the Foundation Skills Assessment tests are administered in Grades 4 and 7. The British Columbia Ministry of Education (2010) reports a sizable gap between the performance of Aboriginal students and non-Aboriginal students in Grade 4 on all areas of assessment (reading, writing, and numeracy). This gap widens further by Grade 7. Aboriginal children are also overrepresented in special education programs and underrepresented in gifted programs (Government of British Columbia 2001).

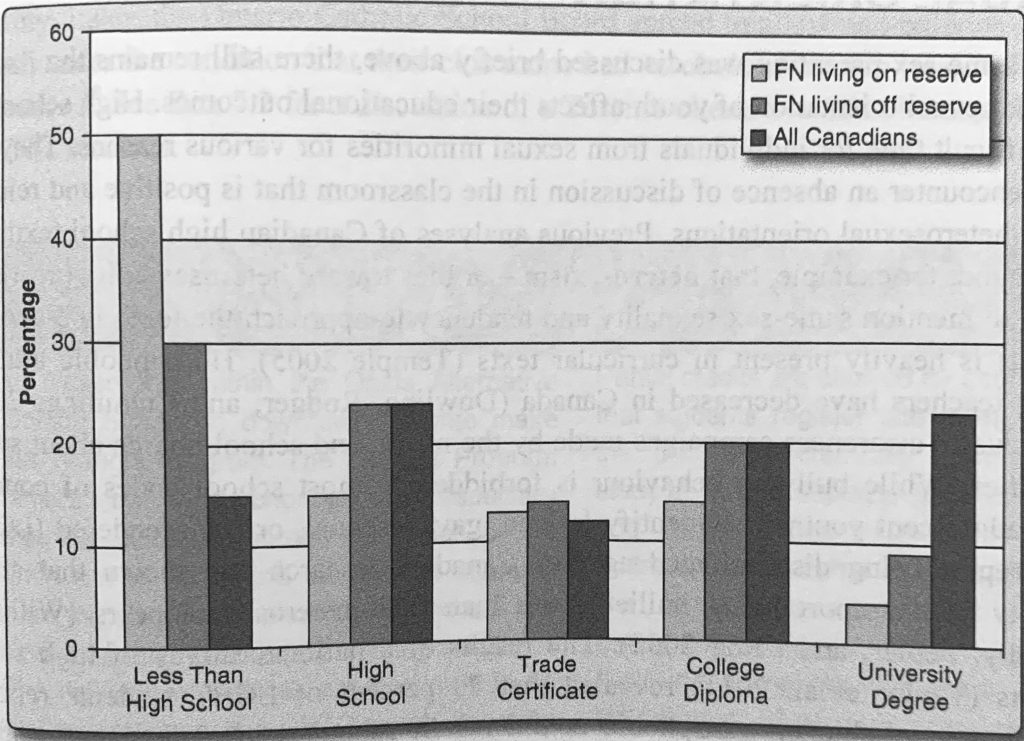

Not doing well in school is strongly associated with school dropout. Aboriginal youth are also more likely not to complete high school compared to non-Aboriginals. These educational attainment differences between Aboriginals and all other Canadians are further accentuated when whether or not an Aboriginal person lives on a reserve is taken into consideration. Aboriginal youth who live on reserves (most who identify as First Nation) attend schools on the reserves that are run by the local band councils, but which are formally under federal jurisdiction. Research has shown that these schools are typically remote, very small, under-resourced, and underfunded (Rajekar and Mathilakath 2009). The remainder of Aboriginal children attend off-reserve schools that are under provincial jurisdiction. As illustrated in Figure 7.5, in 2006, 15 percent of all Canadians did not have a high school diploma, compared to 30 percent of Aboriginal people living off reserve and half of Aboriginals living on reserve.

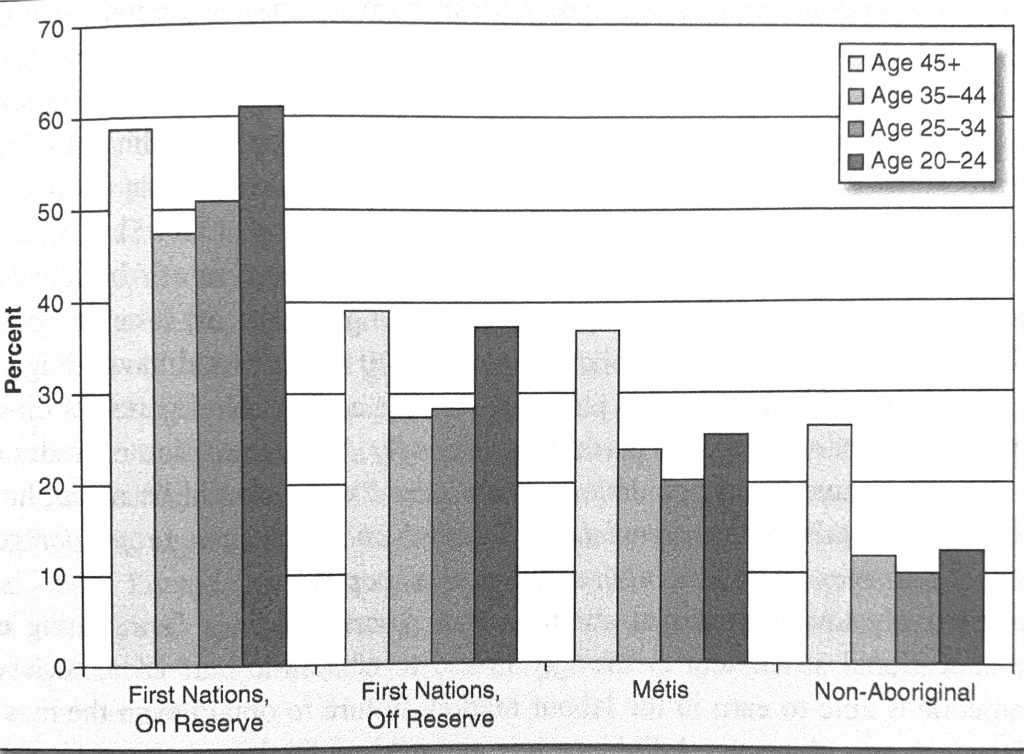

There is some evidence that the educational attainment gap between Aboriginals and other Canadians has somewhat widened. In 2001, 6 percent of all Aboriginals had a university degree compared to 20 percent of all other Canadians—a 14-point difference, which has since grown slightly larger to 15 percent in 2006. Figure 7.6 shows the percentage of Aboriginals without high school certification, by age group (this time broken down into First Nations living on and off reserve, Métis, and non-Aboriginals who did not complete high school). It would be reasonable to expect that each successive generation of Canadians, regardless of ethnicity, would be more likely to get a high school diploma. If we look to trends across different generations, we can see that the overall educational attainments of Aboriginal groups (and non-Aboriginals) made considerable gains between the age 45 and older group and the next youngest group (35–44) as more and more people got their high school certification. But in the next youngest generation shown (age 25–34), there are noticeable reversals in the trend. Among on-reserve First Nations, almost 51 percent of the youngest cohort shown here did not complete high school. Similarly, the number crept up slightly to just over 28.3 percent of those living off reserve. The biggest decrease in high school dropouts between ages 35–44 and 25–34 was seen among Métis, although the lowest rate overall (10 percent) is observed in non-Aboriginals. And in the youngest generation, the result is even less encouraging, particularly for First Nations youth, whose levels of high school dropout are regressing to those of previous generations.

Source: Census 2006, author’s own calculations, www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/as-sa/97-560/p20-eng.cfm

Source: Statistics Canada 2006 Census online tables, www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/as-sa/97-560/p20-eng.cfm

Educational attainment is a strong predictor of high school completion. As discussed above, Aboriginal children tend to do worse on standardized tests than other Canadian children—and this gap widens as children get older. The failure to succeed at school is strongly associated with dropping out, which strongly reduces the likelihood of an individual completing post-secondary education. Aboriginal participation in post-secondary education is substantially lower than for other groups (Finnie et al. 2005). About 23 percent of all Canadians have university degrees, compared to 9 percent of Aboriginals living off reserve and only 4 percent living on reserve. The figures for off-reserve Aboriginals and all Canadians are identical for college diplomas (20 percent) and having high school as the highest level of completion (24 percent)—but the comparable figures for on-reserve Aboriginals are 15 percent and 14 percent, respectively. The acquisition of trades certificates is about the same in all populations (see Figure 7.6). It should be noted, however, that among Aboriginals who do complete high school, about the same proportion go on to some form of post-secondary education as the general population.

The relatively low educational attainment of Aboriginals has far-reaching effects. Because educational attainment is strongly linked to economic outcomes, such as how much someone is able to earn in the labour market, failure to obtain even the most basic credentials such as a high school diploma puts many Aboriginals at a severe disadvantage in the workforce.

Sexual Orientation

While same-sex parenting was discussed briefly above, there still remains the issue of how the sexual orientation of youth affects their educational outcomes. High school can be a difficult time for individuals from sexual minorities for various reasons. They will likely encounter an absence of discussion in the classroom that is positive and relevant to non-heterosexual orientations. Previous analyses of Canadian high school textbooks have found, for example, that heterosexism—or bias toward heterosexuality (as well as failure to mention same-sex sexuality and tendency to approach the topic in a negative context) is heavily present in curricular texts (Temple 2005). Homophobic attitudes among teachers have decreased in Canada (Dowling, Rodger, and Cummings 2007), likely due to awareness campaigns made by the media and school boards about sexual minorities. While bullying behaviour is forbidden in most school codes of conduct, many adolescent youth who identify lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgendered (LGBT) often report being discriminated against. Canadian research has shown that sexual minority youth report being bullied more than their heterosexual peers (Williams, Connolly, Pepler, and Craig 2005). The results of a national survey of high school students (Taylor et al. 2011) revealed that 70 percent of LGBT students reported hearing homophobic or transphobic comments in school daily from other students (e.g., “That’s so gay”), while 10 percent indicated that they had heard such comments from teachers on a daily basis. One in five had reported being physically assaulted due to their sexual orientation.

Schools vary from having explicit anti-homophobia policies to having no anti-homophobia policies, and the study by Taylor et al. (2011) suggests that such policies make a difference in how safe schools are for LGBT youth in Canada. Students who attended a school with an explicit anti-homophobia policy were significantly less likely to report experiencing physical or verbal assault at school. Many LGBT youth also reported missing school due to fear of being bullied. LGBT youth have higher dropout rates and lower educational aspirations (Saewyc et al. 2006), as well as higher rates of depression and psychological problems, than “straight” youth (Savin-Williams 1999; Williams et al. 2005).

Student organizations called gay-straight alliances (GSAs) have become increasingly popular in North American schools (including universities), where they serve to create a positive environment for students who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered, or queer. Various alliances exist in Canadian schools. The website www.mygsa.ca provides a list of all gay-straight alliances in Canadian schools. The site is organized by Egale, a national LGBT human rights organization. At the time of writing, over 130 GSAs across Canada were listed on the website. Research has shown that GSAs can improve the psychological well-being and safety of sexual minorities in school (Goodenow, Szalacha, and Westheimer 2006).

The topic of gay-straight alliances made headlines in early 2011 when it was revealed that students trying to start a gay-straight alliance in an Ontario high school were not permitted to do so. Officials from the Ontario Catholic School Board stated that such clubs would run counter to the teachings of the church, which do not advocate homosexuality. Later, the Ontario Catholic School Board agreed to allow anti-bullying groups instead, under the condition that their club name had no obvious links to issues of sexual orientation.19 See Box 7.2 for a discussion of a Toronto alternative school that is focused on LGBT students.

Box 7.2 – The Triangle Program

Three classrooms within the Oasis Alternative Secondary School in downtown Toronto make up the Triangle Program. The Triangle Program is Canada’s only high school program especially created for LGBTQ20 youth. The goals of the program are to foster the success of students who are targets of homophobia and who are at a high risk of dropping out or committing suicide.

The classroom activities are designed to be particularly relevant to LGBTQ youth. Morning activities are oriented toward completing high school credits, either independently or in groups, with the assistance of teachers and volunteers. Partial credits are allowed for courses in the case that students register late in the year or leave the program. Afternoon activities involve the study of various subjects (science, social studies, and English) that have been redesigned to address the concerns of the LGBTQ communities. An attendance rate of at least 80 percent must be maintained in order to keep a student’s place in the Triangle Program. In the 2009–2010 school year, 63 students were registered in the Triangle Program.