5 The Role of Curriculum

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to

- Describe how Canadian curriculum was shaped by socio-historical processes from pre-industrial Canada to the present day.

- Identify the three influences on curriculum and describe how they influence what is taught in schools.

- Identify the two main ways that curriculum accountability is maintained.

- Compare how the different large-scale assessment practices in Canada vary by province and territory.

- Contrast the six arguments that are for and against large-scale assessments.

- List the five stages of multicultural education that have occurred in Canada.

- Identify two key conflicts in the implementation of multicultural curriculum.

- Identify two ways that multicultural education is being addressed in Canadian curricular practices.

- Describe how in some parts of Canada adjustments have been made to the curriculum to incorporate Aboriginal and ethnic minority perspectives.

- Define White privilege and how anti-racist pedagogies can be used to promote multicultural education.

Introduction

Curriculum is the content of schooling. It is that which is learned in the schooling environment. This is not limited simply to familiar subjects like mathematics, science, or reading. The curriculum is significantly more far-reaching. It also prepares students to become future workers and citizens. And it is because of this socializing nature of the curriculum that it is a topic of enormous sociological interest.

The curriculum is a social construction with many embedded and taken-for-granted assumptions about what knowledge should be transmitted to young people. Who decides what goes into the curriculum? What assumptions about knowledge are engrained in Canadian curricular practices?

Because education is under provincial and territorial jurisdiction in Canada, each province and territory has its own ministry of education that has an official curriculum guide for teachers to follow. These are official documents and the following of the curricular guides is mandatory for teachers. Curriculum guides tell teachers what should be taught and when (i.e., in what order and how much time to allocate to specific topics). The detail of the curricular documents, however, varies greatly from province to province. The method by which the teacher chooses to teach the topic is entirely up to them. Teachers learn about ways of teaching specific topics as part of their teacher training (which also follows curricular guidelines, but at a post-secondary level).

Historical Events in Canadian Curriculum Development

Developments in curriculum cannot be completely understood if the social, cultural, and historical contexts in which they occurred are not taken into account. The context of what is taught at school has been an ideological battleground, with various religious, economic, cultural, and political advocacy groups playing major roles at different points in history. A thorough overview is well beyond the scope of this textbook, discussion, but a brief summary (drawn primarily from the much more thorough overview given by Tomkins 2008) will help contextualize major curricular shifts that have happened across this vast country. Figure 5.1 summarizes some of the major historical events in Canada and how they influenced what was taught to children.

| Larger Historical Events | Years | French Canada | English Canada | Residential Schooling |

| Pre-industrial Canada

English settlers arrive in Upper Canada |

1600s-1700s | Jesuit Ratio Studiorum | Informal parent and church-regulated system | |

| United Province of Canada (1841)

British North American Act (1867) |

1840s-1890 | Church controlled schooling | Egerton Ryerson embarks on curricular development | Aboriginals children removed from their families and forced intro residential schools. This practice did not end until 1996.

|

| Massive influx of immigration (1892-1920)

First World War (1914-1918) Second World War (1939-1945) |

1890-1945 | Missionaries provide informal schooling | Mandatory attendance laws (1920s)

New Education introduced (1930s) New Education gains popularity (1940s) |

|

| Cold War (1947-1991)

Quiet revolution Quebec French language legislation Official Language Act (1974) |

1945-1990s | Revamping of entire Quebec school system (1970s) | Refocus of rigour to math and science (1960)

Changes to curriculum to respond to demands of Aboriginals, French Canadians, women, and ethnic minorities (1970s) Increased centralization (1980s) Large-scale reforms in many provinces (1990s) |

Pre-Industrial Canada

Until the 1840s, education was largely in the hands of the family and the church. Prior to this time, Canada was a pre-industrial society which was mostly based upon agriculture. In New France and English Canada, a systematic curriculum for the education of young people was not established until the 1840s. The 1600s, however, marked the creation of the Jesuit Ratio Studiorum in New France, which was a plan of studies for males who wanted to enter the priesthood. In 1635, the Jesuit College was founded in Quebec, which provided training of priests, as well as males of the upper classes pursuing esteemed vocations. Formal schooling at this point in time was largely limited to the social elite. Similarly, the education of girls in Quebec coincided with the arrival of the Ursulines (a Catholic order of nuns) in 1639. Their school, opened in 1657, focused on teaching the doctrine of the Catholic church, but also the “three Rs” (reading, writing, and arithmetic). Domestic skills were also included in the curriculum. Education in Upper Canada and the remainder of what is now known as Canada was not established until later in the nineteenth century due to lack of settlement.

It was not until the late 1700s that English settlers arrived and settled permanently in Upper Canada. It was the case that schooling was simply not widely available in Upper Canada prior to 1840. In other parts of Canada, the situation was similar. For example, in New Brunswick, a “moving school” was introduced, which required that teachers in different parishes “keep” school in turn. The curriculum at the moving school focused on the three Rs and Protestant biblical teachings. While uptake was high, most children only attended school for a maximum of four years, and attendance during those four years would not likely be consistent. In western Canada, formal education was also closely associated with churches.

Victorian Canada (1841–1892)

In 1841, the United Province of Canada reunited Canada West (Upper Canada) and Canada East (Lower Canada) after several years of armed rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada. Large-scale immigration from England, Scotland, and Ireland meant that the population was growing rapidly. Industrial technology emerged in the form of manufacturing and the development of the railway, and many new immigrants were drawn to cities.

Egerton Ryerson, whose work on establishing education in Upper Canada was described in Chapter 3, is considered to be Canada’s first major advocate of curriculum development. Serving as chief superintendent of schools in 1846, he was concerned about the lack of a formally established curriculum, and expressed concern that such a curriculum was necessary to assimilate the large numbers of immigrants that had arrived in Upper Canada. His focus was on organizing a curriculum for Upper Canada, and his efforts in Upper Canada were later adopted by other school promoters across Canada. Upper Canada was where the mass of the population existed and was therefore a logical starting point for Ryerson. Ryerson travelled extensively and studied school systems internationally in order to bring Canada in line with existing educational practices in other countries, borrowing heavily from Ireland, Scotland, Prussia, France, and Massachusetts in the United States. As discussed in Chapter 3, he spent the 1840s to the late 1870s developing the public school system in Upper Canada.

Ryerson’s vision of education led to the implementation of ideas such as departmental control over the use of particular textbooks and curriculum. He also advocated for the education system to be subjected to equitable public funding as well as to be open to inspection and scrutiny. The idea of textbooks, school libraries, common curriculum, public funding, and accountability is engrained in our understanding of education systems now, but in the 1840s these were quite radical suggestions that were met with a great deal of resistance. Despite being a member of the clergy, Ryerson was also a strong advocate of non-sectarian schools, and many of his reforms reflected his desire to keep control of the schools in the public domain rather than in the hands of the Church of England. English language and literature, mathematics, geography, history, and natural sciences were core to Ryerson’s proposed curriculum. Central to Ryerson’s curriculum was also a “Common Christianity” that he envisaged would educate young people toward a shared sense of morality and duty.1

In Atlantic Canada, provincial boards of education were established in the late 1840s and early 1850s. The prescribed curriculum was one that was meant to be non-denominational. Curriculum development was very similar in western Canada after Confederation in 1867. Non-sectarianism was again strongly prescribed. The rest of Canada developed similar patterns of non-sectarian school curriculum development as they joined Confederation and established their own provincial education acts. The two provinces that deviated the most from “Ryerson uniformity” were Quebec and Newfoundland. Tomkins argues that the case of Newfoundland is explained by its extreme denominationalism (Protestant/Catholic divide) and late entrance into Confederation. In Quebec, religious and linguistic communities played a larger role in the control of schooling, leaving it out of the government’s jurisdiction.

Modernization and Curricular Reforms 1892–1920

Canada’s population dramatically increased between 1892 and 1920 due to mass immigration. During this time, about four million new inhabitants arrived in Canada. The Yukon (1898), Alberta, and Saskatchewan (both in 1905) also joined Confederation between these years, adding to Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, the Northwest Territories, British Columbia, Prince Edward Island, and Manitoba, which had joined earlier. Canada at this time was engaged in country-building and the “Canadianization” of new immigrants, which continued to be an overarching curricular objective. Growth of Canadian schools at this time is also greatly attributable to laws instituted around compulsory attendance. All provinces except Quebec had mandatory attendance laws by 1920. Increased enrolments and population growth meant the massive expansion of the Canadian education system.

In the early 1900s, New Education was introduced in English Canada, which incorporated less traditional topics of study into the classroom. Traditionally, the subjects covered in formal schooling focused mainly on English (literature and grammar), mathematics, learning Latin, and the rote learning of historical dates and geography. New Education introduced the subjects of home economics (“domestic science”), agricultural studies, and physical education to the curriculum, but not with uniform success. Kindergarten was also introduced as a New Education reform. At this point in history, the major purpose of public education in English Canada was to assimilate the large numbers of new immigrants at the time to dominant Anglo-Saxon values and to keep the Canadian curriculum free of American influence. See Box 5.1 for a discussion of the content of curriculum during this time in Canada’s education history.

Box 5.1 – Early Textbooks in English Canada: Loyalty to the British Empire and Christian Values

The introduction of the required use of specific textbooks in the classroom was a hallmark of the beginnings of the education system in English Canada. Under the influence of Egerton Ryerson, the required textbooks in Upper Canada were initially (1846) readers adopted from Ireland. This may seem like a curious choice, but Ryerson rationalized that these texts were more suited to the Canadian temperament and, more importantly, did not contain American influence. The creation of a Canadian identity in education was central to the curricular objectives at the time. A Canadian series of these readers was created in 1867.

But what was in these readers? These textbooks contained the messages about what constructed a model citizen. Baldus and Kassam (1996) analyzed the schoolbooks used in Upper Canada between 1846 and 1910. They found that the books of that time reflected the morality of the upper class. They argue that accepting the social order was a major concern for British conservatives in Canada, and that schoolbooks repeatedly emphasized working hard and the acceptance of suffering and of one’s place in the social order.

Van Brummelen (1983) examined the content of textbooks in British Columbia between 1872 and 1925. Like texts in Upper Canada, loyalty to the British Empire was also found to be a strong underlying theme. The books used in British Columbia, however, strongly emphasized literal interpretations of the Bible, although this decreased significantly by the late 1880s. Van Brummelen documents how the early textbooks from the 1870s conveyed a literal interpretation of the Bible, including discussions about history. For example, the Biblical stories of Adam and Eve and the Tower of Babel were interpreted as actual world history events in the earliest texts. Christian beliefs were emphasized as mandatory to live a useful and productive life. The literal interpretation of the Bible loosened over time and the messages shifted to a more general emphasis on promoting a common Christian sense of morality which prevailed into the 1930s.

Van Brummelen argues that the books chosen reflected the values and morals of a small group of educational leaders. This is how they thought children should be socialized. The contexts of these books must be understood in tandem with the social climate of the time, however. As Van Brummelen concludes, “. . . with a vast and only sparsely settled expanse, with the constant threat of American annexation, with an often hostile native population, with a plurality of nationalities and religions, with poor communication and transportation, and with an almost non-existent sense of national identity, it would have been surprising if textbooks, and consequently, schools, had not held before the students a common Canadian vision of life and society that the leaders wanted to inculcate” (p. 24). A significant part of that vision included socialization into Christian values. However, Sheehan (1990) argues that across Canada, loyalty to the Empire was an important message found in readers that were used in most provinces in the early twentieth century.

1920 to Post–Second World War

In the 1920s, New Education and similar reform efforts continued to gain popularity as British educators (influenced by progressive movements in the United States) continued to argue that education should be more encompassing than just the three Rs. Learning purely through memorization was also regarded as a less acceptable pedagogical practice than it had been in the past, with more attention being shifted to the possibilities of students engaging in experiential learning. The late 1930s and early 1940s saw the beginnings of the progressive education movement, which is a pedagogical approach that prioritizes experiential learning (i.e., learning through doing and experiencing) over the amassing and memorization of facts. Reforms of this era were characterized as being more child-centred, activity-based, integrating various subjects where possible (Lemisko and Clausen 2006). For example, social studies emerged as a subject, which was the result of combining geography, civic education, and history. The content of this course, offered across grade levels, was based upon developing democratic and cooperative behaviour through experiential learning. Alberta led all provinces in adopting major revisions to the curriculum in the late 1930s that promoted progressive education, with other provinces following in the 1940s.

Post-War Curriculum Changes: 1945–1980

Although a mandate of Ryerson and many other education advocates of his time (and later) across Canada was to avoid American influences in curriculum, many American ideas found their way into Canadian curriculum in the post-war years, including the idea of scientific testing. The cultural content of the English Canadian curriculum, however, remained British. In fact, throughout curriculum development in Canada, there have often been marked efforts to keep the curriculum “Canadian” and culturally distinct from that used in the United States (Sumara, Davis, and Laidlaw 2001). Topics of study were British, although education influences were recommendations that had been adapted from prominent British educators through the influence of American education advocates.2

The Cold War era, or the years following the Second World War, was associated with competition and political tension between the Soviet Union and its communist allies and the Western world—primarily the United States. Competition between the opposing sides manifested itself in two important ways. The first was the “Space Race”—which referred to a rivalry between sides as to which nation could lead in technological space exploration. The second area of major competition was the more ominous Nuclear Arms Race, in which the U.S. and the Soviet Union engaged in the stockpiling of nuclear arsenals. In these years the English Canadian curriculum followed the American lead and added more curricular emphasis on science and mathematics to reflect public opinion that remaining competitive with the Russians (who were thought to excel in these areas) was paramount.

The mid-1960s is associated with another major shift in curriculum across Canada. In English Canada, much pressure was put on the educational system to change in order to respond to the newer values and worldviews emerging at the time. In addition to less centralized control of schools and an increase in the regional specificities of courses of study, schools had to respond to demands from students and members of the public who had various concerns. Students wanted more “practical” knowledge that also reflected a more diverse (non-British) population. Advocacy groups cropped up in the form of federal agencies, consumer organizations, organized labour, and human rights organizations. These groups viewed classrooms as an ideal place to cultivate their desired social changes. Many rights movements also occurred in the 1960s—Aboriginal Civil Rights activism (as well as the Civil Rights movement in the United States) and the second wave of feminism across Canada, the UK, and the United States drew attention to racial and gender inequalities. During this period, advocacy groups representing Aboriginal and various minority groups moved to press for multicultural, non-sexist, and non-racist treatments of subject matter.

At the same time that pressures were being made to make the English Canadian curriculum more progressive, the Quiet Revolution was occurring in Quebec. Up to this point, the schools in Quebec were run by the Catholic Church. In the early 1960s, Quebec completely overhauled its education system, replacing Catholic Church leadership with government administration. The reasons for this change were manifold, but at the core was the desire of the leaders in French Canada to achieve a workforce that had the essential qualifications to modernize Quebec both economically and culturally. In the 1970s, Quebec introduced controversial legislation that required all new immigrant children (which included children from other Canadian provinces) to be educated in French rather than English. These school reforms were all considered essential by leaders who sought to overturn what they believed to be a francophone disadvantage resulting from of hundreds of years of marginalization under Church and British domination.

Since the 1970s, additional shifts have occurred in curriculum across Canada. The 1980s was marked by an increase in centralization (after decentralization in the 1960s) to create more accountability. Standardized testing was re-introduced (after having previously been abandoned) and more focus was again placed on skill performance in reading, writing, and mathematics. Teachers resisted these top-down demands and insisted on being included in decisions around curriculum reform. The inclusion of teachers in curriculum reform became accepted practice in the 1980s.

1990 to Present Day

The 1990s were again characterized by large reforms in several provinces that were in response to various factors including the perceived poor performance of Canadian students in international rankings as well as high dropout rates. Inclusiveness was also emphasized in the reforms, with efforts to engage and represent a wider diversity of perspectives. A basic core academic curriculum, to be completed by all, was supplemented with alternative subjects within which a student could pursue his or her own interests. This new curriculum was adopted with the mandate of responding to the diversity of the population and better preparing young people for the labour force. New high school curriculum emphasized career-related skills (e.g., skills in technology and communication) in addition to academic study, with the intention of preparing students to be productive future citizens with a variety of skill sets. An anticipated outcome of accommodating a more diverse student population was the retention of students who would otherwise be at high risk for dropping out.

While curriculum has historically been provincially specific to fit the needs of a diverse population, the Council of Ministers of Education (CMEC) was established in 1967 in order for provinces to collaborate on common curricular goals. The CMEC has, for example, coordinated a number of student assessments that are administered across the country (discussed in more detail below). The first development of CMEC was the Pan-Canadian Science Project (PCSP), which was aimed at producing a science curriculum with the same learning outcomes across all provinces and territories for kindergarten through to Grade 12. Science was chosen as the first area of cooperation due to the perceived importance of scientific literacy in wider scope of the economy, and in order to keep up with the American science curriculum reforms that had been underway since the early 1990s (Percy 1998). The materials on this project are available for individual provincial and territorial jurisdictions to incorporate into their science curricula (Dodd 2002). Many provinces have implemented the PCSP.

In 1995, a Pan-Canadian Protocol for Collaboration in School Curriculum was adopted in order to improve the overall education quality across provinces and territories and also to foster cooperation between the jurisdictions. In 1993, education ministers in the western provinces and the Yukon and Northwest Territories signed the Western Canadian Protocol for Collaboration in Basic Education (K–12), with Nunavut joining in 2000. A similar alliance was created among the Atlantic provinces in 1995 with the establishment of the Atlantic Provinces Education Foundation. The mandate of the Western Canadian Protocol and the Atlantic Provinces Education Foundation is to create common curriculum outcomes and methods of assessment between the jurisdictions (Dodd 2002).

Influences on Curriculum

While there is general consensus that it is of fundamental importance to educate children and young people, the specific content of that education is subject to debate. Parents are a major source of influence on the curriculum, as are political/cultural organizations and corporations.

Parental Influence on Curriculum

Parents, unsurprisingly, often exert influence on the content of children’s education. Most often this occurs when parents feel that what is being taught (or being proposed to be taught) contrasts sharply with the morals and worldviews that they wish to have instilled in their children. Parental influence can also be found in parent or school councils, which were discussed in Chapter 4 (Parker and Leithwood 2000).

While subjects like reading are regarded as essential skills, what children are permitted to read in class continues to be a topic that can create much debate. The Freedom of Expression Committee (www.freedomtoread.ca) monitors censorship issues in Canada, including books that parents have made cases for removing from school curricula and libraries. Jenkinson (1986) indicates that most advocates of banning particular books in schools are individual parents. The annual lists compiled by the Freedom of Expression Committee reveal that in 2009 at least 74 “challenges” were received by the Canadian Library Association about library holdings that at least one person wished to have removed. In the previous year, this number was 139. For example, in 2008, a parental complaint in Toronto argued for the removal of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale from a Grade 12 English class on the grounds that it used profanity and described violent scenes involving sexual degradation. The school board retained the novel in the curriculum. In 2002, Black parents and teachers in Yarmouth, Digby, and Shelburne, Nova Scotia, challenged Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird and Barbara Smucker’s Underground to Canada on the grounds that they contained language that was derogatory to Black people. Parents expressed concern that it could lead to racial stereotyping and to their own children being mocked. Ultimately, these books were not removed from the school library.

Often, the challenges that parents have are rooted in religious beliefs that they feel are being undermined by curricular content. For example, in 2000, the Durham, Ontario, school board received many complaints that the popular Harry Potter books by J. K. Rowling were being read in schools. An official from the school board said that the complaints were coming from fundamentalist Christian parents who were concerned that the wizardry and witchcraft that the main character practised was inappropriate for adolescents. In other jurisdictions across Canada, some teachers have been asked not to use these books in the classroom, and similar issues have arisen in 19 U.S. states. This is just one of many examples of parents and members of the public “challenging” books in schools.3

With regard to science, Darwin’s theory of evolution and the Big Bang theory can be viewed as problematic by certain religious groups who believe that the universe and humankind was created by a supreme being. Many fundamentalist groups have opposed the teaching of these topics in the classroom, as they run counter to their own beliefs. They have also suggested that perspectives such as creationism and intelligent design, which support their views, also be taught alongside Darwinism and the Big Bang theory as legitimate alternatives. Many religious groups also oppose the exposure of their children to many topics including sexual health education and climate change. The curriculum varies widely by province, as does teachers’ knowledge of the topic (as well as their personal beliefs).

Political/Cultural Groups’ Influence on Curriculum

It is not exclusively individual parents who challenge curricular content; sometimes organizations representing political, religious, or cultural viewpoints also oppose curricular materials. In 2006, for example, the Canadian Jewish Congress challenged Three Wishes: Palestinian and Israeli Children Speak, by Deborah Ellis.4 They argued that this book should not be accessible to elementary school children because it presented a flawed and one-sided view of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. While the book was not removed from schools, five school boards in Canada set restrictions on its access (e.g., limiting its access to higher grade levels and requiring that the title be removed from shelves and available only by request).

In 2007, the Council of Turkish Canadians challenged Extraordinary Evil: A Brief History of Genocide by Barbara Coloroso on the grounds that the deaths of millions of Armenians during the Ottoman Empire was described as genocide. (The Turkish government disagrees that this was genocide.5) This book was to be used in Toronto in a Grade 11 history class on genocide. A committee of the Toronto District School Board deemed the material to be an inappropriate depiction of factual history and it was removed from the reading list. This decision was met with much protest by writers, Canadian publishers, and the Book and Periodical Council, which led to it being put back on the reading list, but as a social psychological resource on genocide rather than a historical text. This reversal of the decision led the Turkish Embassy to complain to Premier Dalton McGuinty and the Ontario Ministry of Education. The book remains on the reading list at the time of writing.

Private-Sector Influence

Many corporations have free resources available for teachers that help with teaching specific topics (Robertson 2005). The corporations provide materials freely to teachers who can easily request them online. A few examples include the Canadian Nuclear Association, which provides “secondary school teachers with access to lesson plans about concepts, issues and people related to the nuclear industry.”6 The resources that are provided are vast and include full lesson plans, downloadable PowerPoint slides, and student assessment materials, all of which are customized to the curriculum requirements of particular jurisdictions. Kellogg’s also has nutrition-related educational resources on a special website called missionnutrition.ca, which includes lesson plans and materials for children from kindergarten to Grade 8. Dove Canada offers a “Real Beauty School Program” for teachers that is aimed at improving children’s self-esteem. Kraft Canada and Sobeys are major sponsors of Prince Edward Island’s Healthy Eating Alliance, which provides several nutrition resources for teachers to use in the classroom.7 Procter & Gamble has partnered with government health agencies at the provincial and federal level to create a “user-friendly, state of the art, puberty education program” which they call the Always Changing and Vibrant Faces program. Procter & Gamble also offers teaching materials for nutrition education aimed at Grade 4 students and “nose-care” instructional materials geared toward Grade 1 students.

How do the Curricula of Different Provinces Compare on Controversial Subjects?

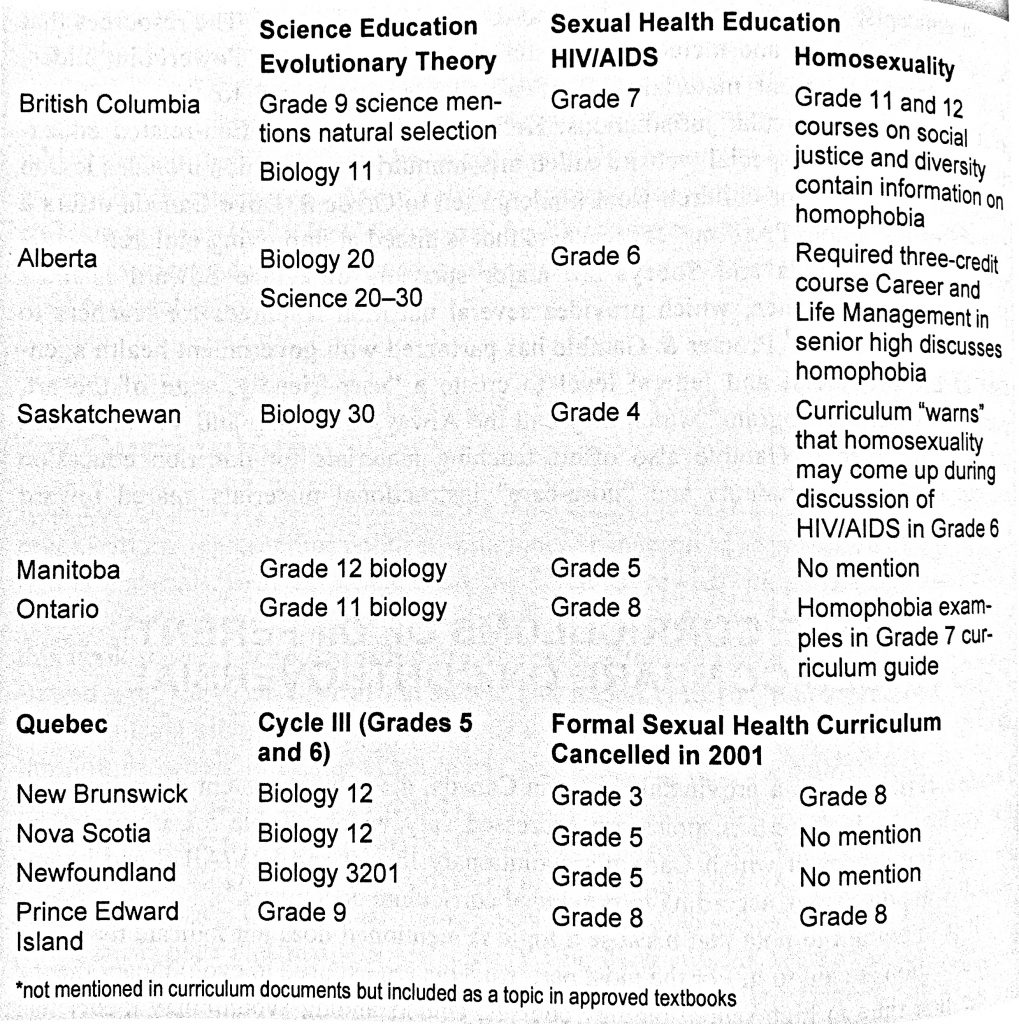

Because curriculum is a provincial matter in Canada, the subject content of courses and the grades at which certain topics are addressed vary widely. Table 5.1 illustrates by province the grades at which Darwin’s evolutionary theory and HIV/AIDS and homosexuality are discussed, according to provincial curriculum documents.8

It is important to note that because a topic is mentioned does not indicate that thorough attention is paid to it. For the most part, students are exposed to evolutionary theory for the first time in high school biology courses. Understanding evolutionary theory has wider implications for a student’s understanding of related issues, such as environmental studies, genetics, and viral mutations (e.g., why we need new flu inoculations every year). Most provinces introduce evolutionary theory in later high school years, although British Columbia, Prince Edward Island, and Quebec begin talking about the topic markedly earlier. Additionally, Asghar, Wiles, and Alters (2007) found in a study of pre-service elementary teachers that most regarded evolutionary theory as scientific fact and that three-quarters of them intended to teach evolutionary theory in elementary school science. They did, however, raise concerns about the religious beliefs of students and their parents and also that they themselves did not receive adequate training on this topic in their own educational trajectories.

As a public health issue, it is arguable that discussion of sexually transmitted diseases is very important, particularly incurable infections like HIV/AIDS. Table 5.2 shows that the first mention of this topic varies greatly by province, from Grade 3 in New Brunswick to Grade 8 in Prince Edward Island and Ontario. Many provincial curriculums have HIV discussions that occur in every year of sexual health education. Quebec does not have an official sexual health curriculum as it was discontinued in 2001 due to funding cuts. Teachers are encouraged to bring up such topics in informal discussions in class. Women’s groups and sexual health workers in Quebec have indicated that the sharp increases in STIs among young people are indicative of the harm caused by this reform in curriculum.9 Homosexuality is notably absent in many provincial curricula as well. Saskatchewan’s sexual health curriculum documents “warn” that the discussion of homosexuality may come up when HIV/AIDS is presented. See Box 5.2 for a discussion of changes to legislation in Alberta that enables parents to remove their children from school when topics that parents disapprove of are discussed in the classroom.

Box 5.2 – In the News: Parents Responding to Curriculum

In mid-2009, Alberta legislators passed Bill 44, a controversial piece of legislation that allows parents to pull their children out of class when religion, sexual orientation, or sexual health topics are going to be discussed. The bill is an amendment to the province’s human rights laws. It is now required that school boards give parents written notice when controversial topics are going to be discussed in the classroom. By giving such notice, parents are given the option to have their children excluded from such lessons. Casual conversations in the classroom around such topics are not covered by this bill.

The bill was protested by many, particularly by schools boards, teachers, and human rights groups, who argued that this legislation makes it possible for teachers and school districts to become the target of human rights complaints from parents. Such a pedagogical environment, they argue, is loaded with tensions for educators who understandably do not want to be the target of such complaints. It is argued that such legislation would have been better dealt with by the School Act, instead of being reconfigured as a human right. The School Act, according to the Alberta Education website, “describes the relationship of the Minister to students, parents and school jurisdictions and provides for the system of administration and financing of education in Alberta and generally deals with the ultimate authority of the Minister with respect to all constituents in the educational system.”10 Section 50 of Alberta’s School Act already permitted exemption of students from patriotic or religious instruction with parental written request.

The union representing Alberta teachers (the Alberta Teachers’ Association) has also expressed concern about “grey areas” of education—the case where sexuality and religion can come into discussion in other topics, such as social studies and literature.

A similar controversy emerged in Ontario in early 2010, when the province proposed to change the new sex education curriculum. The proposed revised curriculum, backed by the Liberal Ontario Premier Dalton McGuinty, was to expand to include Grade 3 students learning about sexual orientation, while Grade 6 students would learn about masturbation. The topics of anal and oral sex were proposed to be taught at the Grade 7 level. Much backlash was received from faith-based groups over the proposed changes to the sex education curriculum, arguing that young children would be exposed to inappropriate materials. The McGuinty government scrapped the proposed changes, arguing that it had not introduced the proposed changes with enough lead time to get feedback from groups and to prepare parents.

Sources: www.cbc.ca/canada/toronto/story/2010/04/21/ont-sexed.html; www.thestar.com/breakingnews/article/799313–mcguinty-postpones-sex-ed-changes?bn=1; www.cbc.ca/canada/edmonton/story/2009/06/02/alberta-human-rights-school-gay-education-law.html.

Curriculum Accountability

Given the considerable amount of decision making that goes into determining what should be included in the curriculum, it follows that provinces and school boards would want to ensure that teachers are following the curriculum and that students are learning its content. How do the provinces and school boards ensure that the curriculum is being followed? In other words, what measures of accountability are built into the school system to ensure that that curriculum is being followed? One formal tool of accountability is standardized testing procedures. Another informal technique is media pressure.

Evaluation and Assessment of Students

Evaluation and assessment of students is often done in the form of testing. In general, there are two ways that teachers can evaluate student work and understanding of materials: formative assessment and summative assessment. Formative assessment refers to ungraded feedback that teachers receive from students during the course of learning material that gives indication as to how the students understand the content. Such assessment tools take the form of drafts of essays or journal reflections (Volante and Beckett 2011). Summative assessment refers to tools used for evaluation at the end of a unit and take the form of quizzes, tests, essays, or projects. Both formative and summative assessments have different functions—the former is used during the learning process to ensure comprehension, while the latter is used at the end to evaluate performance. Formative assessment has been found to improve student learning and thereby enhance summative assessment, although the use of formative assessment practices varies greatly between teachers (Volante and Beckett 2011).

In addition to formative and summative assessment, standardized testing also occurs across Canada. Standardized testing is the process of giving the same curriculum-based test to all students at a particular level in a particular jurisdiction. Because each province and territory governs its own education system, these types of assessment exams—or large-scale assessments (LAS)—vary considerably across the country. The objective of assessment exams is to evaluate how well students are achieving according to the curriculum mandates of that particular province/territory. It is one way that accountability is maintained. If the curriculum is being followed, it is argued that the students should achieve well on tests that are developed according to the learning outcomes associated with the curriculum. While testing in most provinces and territories occurs across the spectrum of K–12, there are many different grades and subject areas that are focused on by the different provincial/territorial government departments.

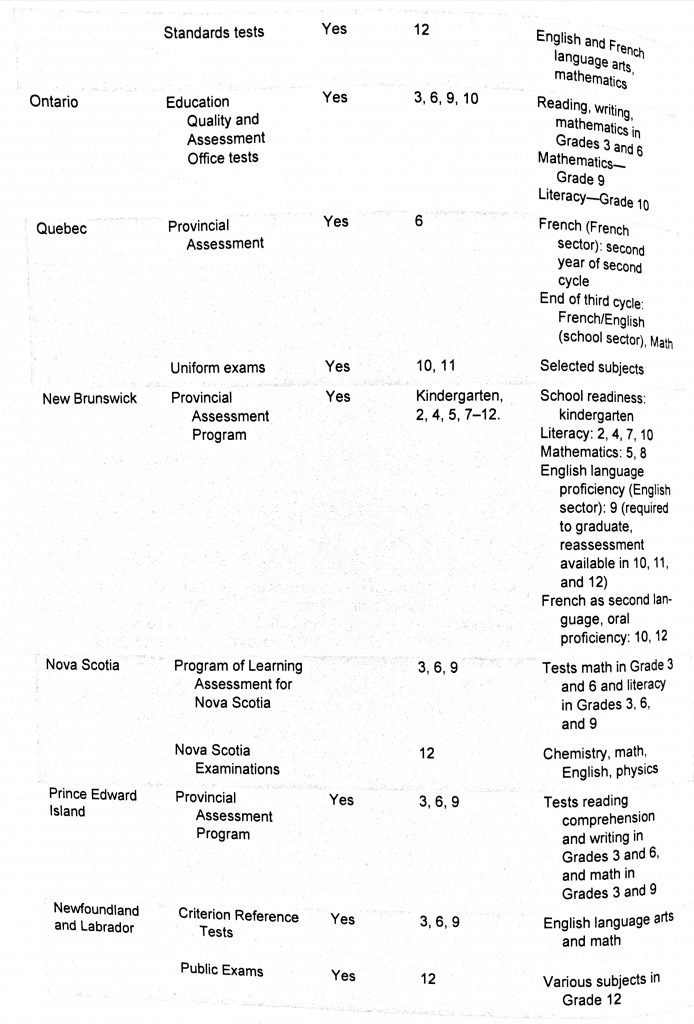

One similarity that the majority of provinces and territories share is the assessment of Grade 12 subjects for graduation and diploma purposes. In such credentialing exams, the assessment is of the performance of the student. These exams serve to assess competency in subject areas and are used by post-secondary institutions to evaluate criteria for acceptance into programs of further study. The exceptions to Grade 12 diploma assessments are in Ontario, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. In Ontario, a literacy test, which is required for graduation, is completed in Grade 10, while Grade 11 students are tested in English and mathematics in New Brunswick (in the English system). Many of these tests at the senior level are high-stakes exams because a percentage of the grade achieved on these tests goes into the calculation of the final grade. These values can vary between 30 percent of a final grade (e.g., Manitoba and Nova Scotia) and 50 percent (e.g., Alberta and Newfoundland). Exams at senior levels are high stakes for the students, but not for teachers or administrators; students must pass to graduate, but educators do not experience official sanctions if students perform poorly (Volante and Ben Jaafar 2008), although they may experience scrutiny in the media (discussed below).

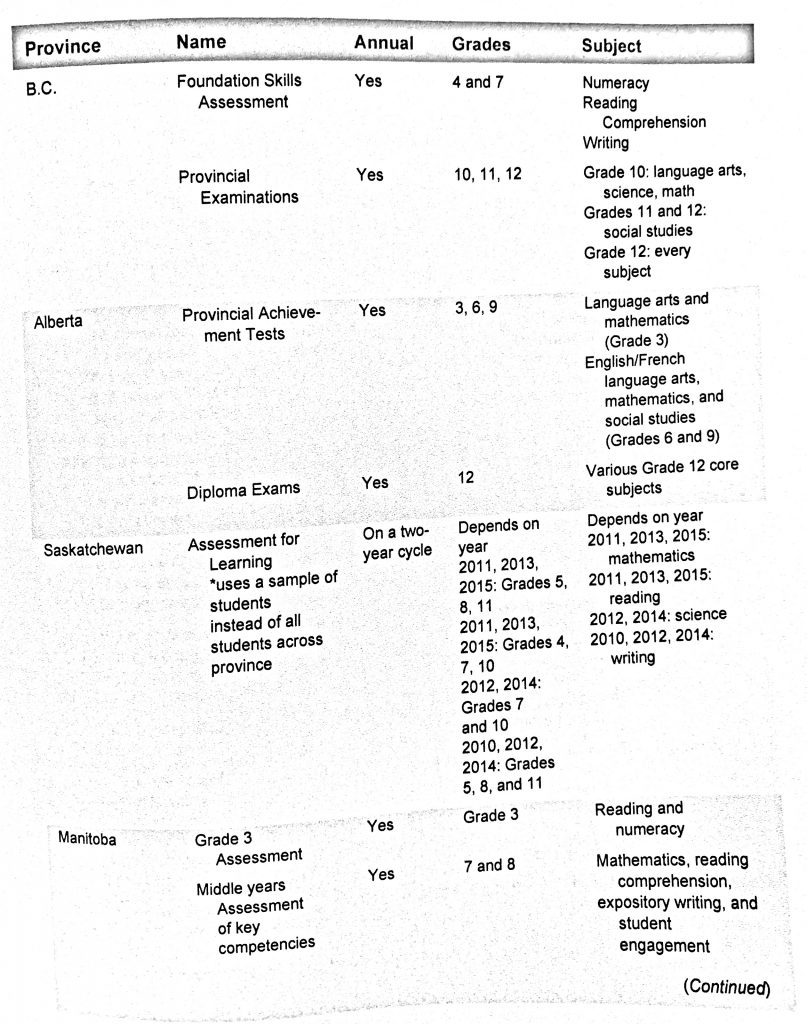

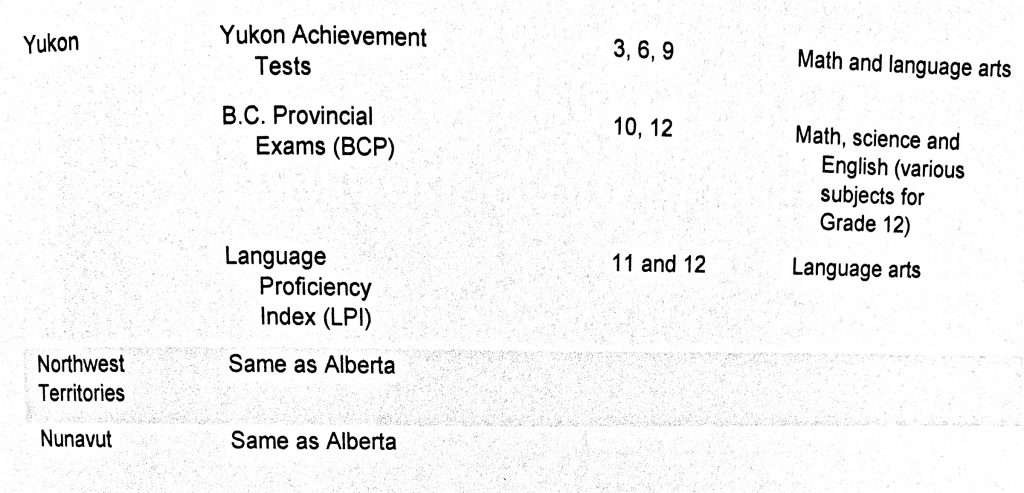

Large-scale assessments also serve to evaluate the performance of programs. Tests are administered in math and English (as well as other subjects) in specific grades in order to evaluate how well students are demonstrating the curricular goals of the province. The grades achieved on these tests have no bearing on the formal assessment of the students’ performance. In Alberta, which arguably has the most extensive assessment procedures in Canada, students are assessed in math and English language arts in Grades 3, 6, and 9, as well as in science, social studies, and French language arts (where applicable) in Grades 6 and 9. There are 11 courses for which there are credentialing exams in Grade 12, and students must write and pass six of them to get a diploma. It should be noted that the high school diploma tests used in Alberta are also used in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. This is in stark contrast to Prince Edward Island, where students have assessment tests for reading in Grades 3 and 6 and for mathematics in Grades 6 and 9, and no diploma exams for high school graduation. British Columbia assesses reading, writing, and numeracy in Grades 4, 7, and 10 and has credentialing exams in Grade 12 in numerous subjects, while Nova Scotia assesses math in Grades 5 and 8, language arts in Grades 6 and 9, and has credentialing exams in English, science, and math in Grade 12. Saskatchewan, in contrast, assesses math, language arts, science, and writing in rotating years with different grades, based on samples of students (rather than all students across the province, like most assessment tests). For example, in 2011, 2013, and 2015, Grades 5, 8, and 11 will be assessed in mathematics and Grades 4, 7, and 10 in reading. In 2012 and 2014, Grades 7 and 10 will be assessed in science and Grades 5, 8, and 11 in writing. Appendix A at the end of this chapter has a detailed description of all the provincial and territorial assessments used in the Canadian school system.

Media Pressure

One outcome of large-scale assessments is that the results are usually made public. It is often the case that the media acquires the results of provincial, national, and international student assessments and reports the results. Some jurisdictions, or even particular schools (depending on the level of detail that is released), are celebrated as being the best schools, while others are noted for being at the bottom of the league tables (i.e., ranking chart).

The Fraser Institute in Vancouver (an independent conservative think tank) has been releasing “report cards” on elementary and secondary schools in selected provinces since 1998. These report cards rank schools according to how well students have done on the large-scale assessments done in these provinces. At the time of writing, the report cards are prepared for B.C., Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec. The purpose of these rankings, according to the Fraser Institute, is that by “combining a variety of relevant, objective indicators of school performance into one easily accessible public document, the school report cards allow teachers, parents, school administrators, students, and taxpayers to analyze and compare the academic performance of individual schools.”11 Each report ranks schools across the province according the scores that children achieved on standardized tests. For each school, information is provided on percentage of ESL and special needs students, enrolment numbers at specific grade levels, parents’ average income, and the school’s overall rank out of all schools in the province. Average test marks are provided for prior years and the percentage of tests failed is also indicated. The schools are given ratings out of 10 on their performance. Any member of the public can download the reports from the Fraser Institute’s website to see how a specific school rates on these criteria.

These ratings are obviously controversial, not only because the measures on which they are based (i.e., large-scale assessments) are also controversial. The Fraser Institute argues that it fairly compares all schools against one another using uniform criteria, whereas critics say that these rankings greatly oversimplify the many factors that contribute to student achievement and pit schools against one another (Volante 2005).

National-level Assessments

With all the differences in assessments that occur across the country, policy-makers have been interested in developing ways to compare the achievement and learning of children across the country. The Council of Ministers of Education in Canada (CMEC) is an intergovernmental body that was created in 1967 by ministers of education across the country. The mandates of the CMEC include representing all the provinces and territories on educational matters as well as monitoring the achievement and skills of Canadian students. CMEC oversees the pan-Canadian assessment of student performance. In 1993, the Student Achievement Indicators Program (SAIP) was introduced, which assessed mathematics in 13- and 16-year-olds. The assessment was based on a random sample of more than 35 000 students across Canada. Reading (1994) and science (1996) assessments were administered in successive years to complete a three-subject cycle of assessments. A second cycle occurred from 1997–1999, and a third from 2001–2004. Information from these assessments is examined at a provincial and national level (i.e., not by municipality).

In 2007, the SAIP was replaced by the Pan Canadian Assessment Program (PCAP) in order to “reflect changes in curriculum, integrate the increased jurisdictional emphasis on international assessments, and allow for the testing of the core subjects of mathematics, reading, and science.”12 The PCAP assesses 13-year-olds across Canada in science, mathematics, and reading. Each year of the assessment gathers information on all subjects, although the larger proportion of the assessment will shift among the three subject years in rotating cycles. In 2007, the focus was on reading, while in 2010 it was on mathematics, and in 2013 it will be on science. Over 30 000 students within 1500 schools were randomly selected from participating jurisdictions (the Northwest Territories and Nunavut did not participate). See Box 5.3 for a discussion of the 2007 results by jurisdiction.

Box 5.3 – Average Reading Scores from 2007 PCAP across Jurisdictions

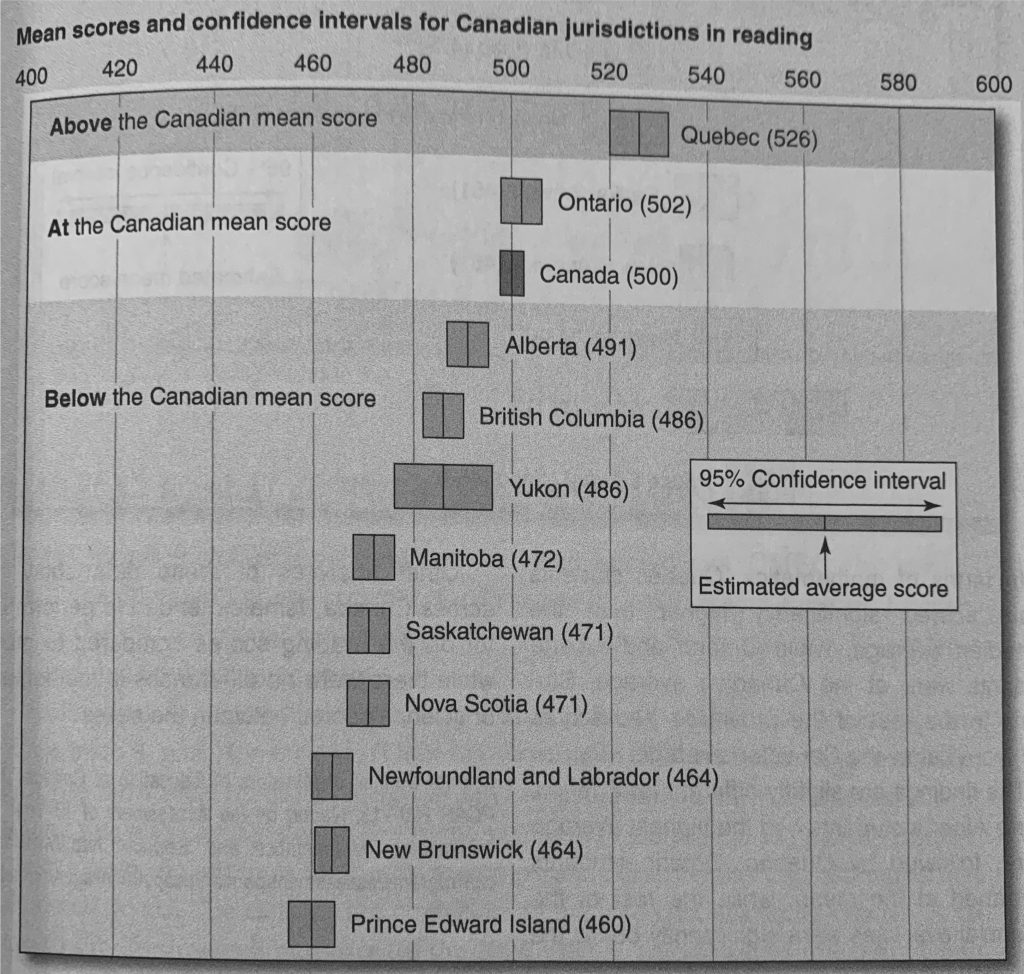

The results from the PCAP allow the performance of students in each of the provinces to be compared to one another. In the first chart, the average (mean) reading scores of students by different provinces are represented, along with the pan-Canadian average (500). The middle of each box shows the provincial average, while the right- and left-hand sides of the box show what is known as the 95 percent confidence interval. The grades themselves do not report the raw average, but estimates of how the population of each province would have done if all students had participated. The confidence interval tells how much precision is associated with that estimate—the larger the interval, the less precise the measurement is. This confidence interval represents where the actual mean is estimated to fall 95 percent of the time.

Looking at the provinces compared to the overall Canadian average, one can say provinces are significantly (in a statistical sense) different only if the confidence intervals do not overlap with one another.

Quebec’s average, therefore, is significantly different (i.e., higher) than the Canadian average in reading. Ontario’s is not significantly different from the Canadian average, but is significantly different (lower) than Quebec. All provinces except Ontario and Quebec performed lower than the Canadian average on reading.

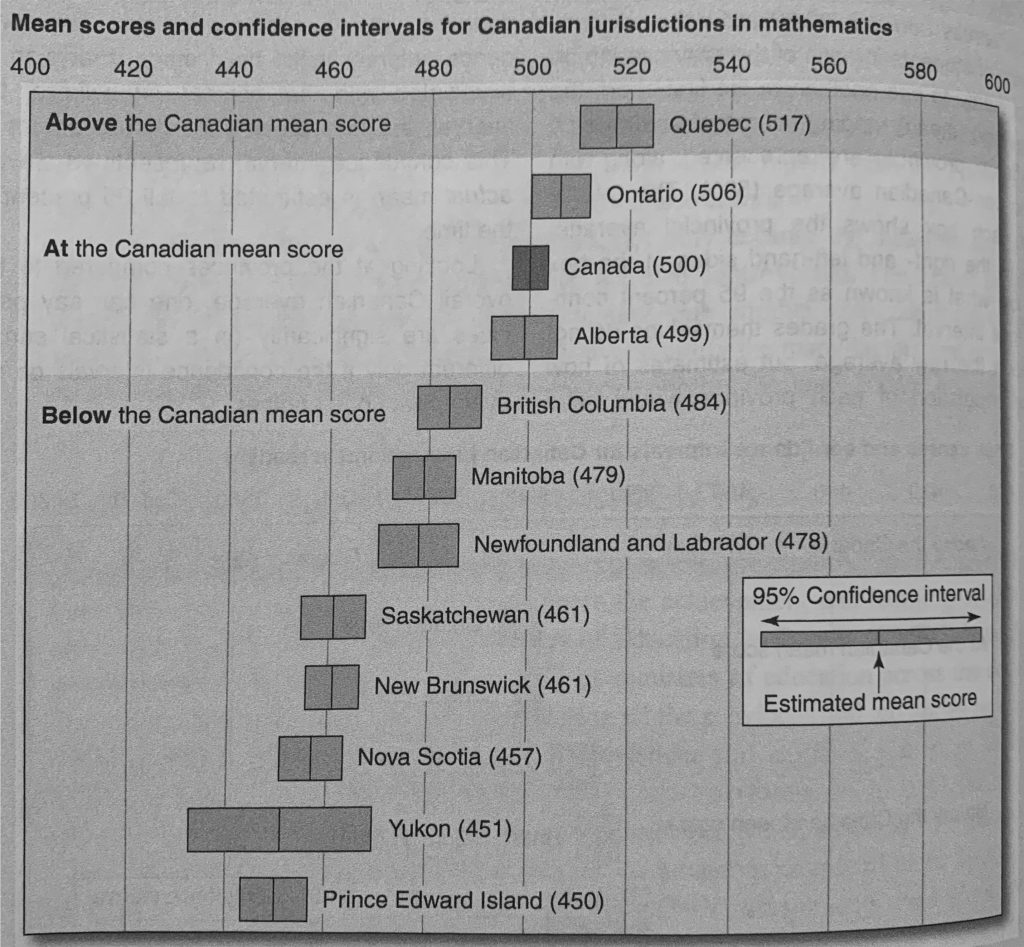

In terms of mathematics, Quebec students again scored significantly higher than the Canadian average, while Ontario and Alberta students were at the Canadian average. Students in the rest of the provinces had scores that were below the Canadian average.

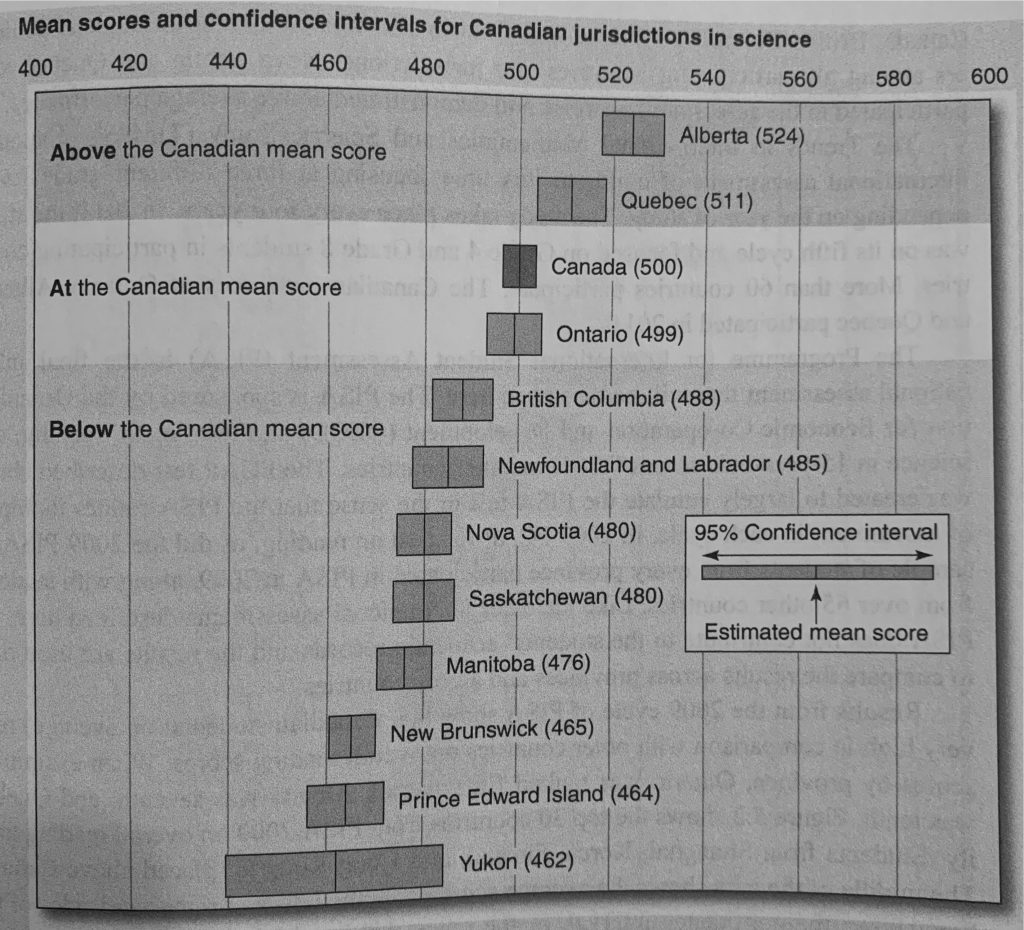

The findings are slightly different for science, where Alberta students had the highest average score, followed by Quebec. Ontario students performed at the mean, while the rest of the provincial averages were significantly below the Canadian mean.

Other analyses of these data show that across Canada, females tended to perform better on the reading scores compared to males, while there were no differences in mathematics or science scores between the sexes.

Source: Council of Ministers of Education of Canada. 2008. PCAP 2007-13. Report on the Assessment of 13 Year Olds in Reading, Mathematics and Science. http://www.cmec. ca/Programs/assessment/pancan/pcap2007/Pages/default. aspx.

International-level Assessments

In addition to provincial/territorial and pan-Canadian assessments, CMEC also participates in three international assessments: the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study, the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study, and the Programme for International Student Assessment.

The Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) is a reading test administered to 9- and 10-year-olds (Grade 4). Starting in 2001 and occurring every five years, it was most recently administered in 2011 to children in over 50 countries. All 10 Canadian provinces participated in the study, which is based upon a sample of children. The results from the tests are used only to compare children across Canada and across jurisdictional levels. The tests do not contribute to the students’ academic records at all and are strictly for research purposes. In the 2006 PIRLS, the Russian Federation, Hong Kong, and Singapore were the top scorers of the countries that participated. Within Canada, British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario also ranked among the highest achievers among all participating countries and jurisdictions. Nova Scotia and Quebec also participated in the assessment exercise and demonstrated above average performance.

The Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) is another international assessment of children, this time focusing at three different grade levels depending on the year of study. The study takes place every four years. In 2011, the study was on its fifth cycle and focused on Grade 4 and Grade 8 students in participating countries. More than 60 countries participate. The Canadian provinces of Ontario, Alberta, and Quebec participated in 2011.

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is the final international assessment that will be discussed here. The PISA is sponsored by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and tests math, reading, and science in 15-year-olds across OECD member countries. The PCAP test described above was created to largely emulate the PISA test in the sense that the PISA rotates its topics of assessment in each cycle. In 2009 PCAP focused on reading, as did the 2009 PISA. A sample of students from every province participated in PISA in 2009, along with students from over 65 other countries. Like the other international assessments described here, the PISA does not contribute to the students’ academic records and the results are used only to compare the results across provinces and across countries.

Results from the 2009 cycle of PISA show that Canadian students (on average) rank very high in comparison with other countries on overall reading scores. When examining scores by province, Ontario was ranked fifth overall, Alberta was seventh, and Quebec was tenth. Figure 5.2 shows the top 30 countries from PISA 2009 on overall reading ability. Students from Shanghai, Korea, Finland, and Hong Kong all placed above Canada. The middle of the bars shows the average score while the left- and right-hand sides of the bars shows the confidence interval, or the range within which the “true score” is estimated to exist. If bars overlap, there is no “significant” difference between the scores. Shanghai’s scores are clearly significantly higher than those of the rest of the countries in the study, while the overall Canadian average score is higher than those of all countries listed below Australia.

Controversies around Large-scale Assessment

Advocates of large-scale assessment tend to stress that these testing mechanisms have several advantages. The biggest advocates of large-scale assessment tend to represent the administration side of education. If the tests are based on curriculum, they allow administrators to examine how closely the curriculum is being followed. Some advocates have even argued that these assessments have the effect of making students try harder (Anderson 1990). The results of such tests can arguably point to the most effective teaching practices and direct attention to areas where more research and/or resources need to be targeted. If a new policy or program is implemented, the results of these assessments can also point to the success or failure in the adaptation to such changes. National assessments allow provincial governments and departments of education to evaluate how children outcomes vary by jurisdiction, while international assessments reveal where Canadian children rank on the global stage and allow educators to ensure that our practices are competitive and effective.

Here is a look at collated information on Canada’s achievement in reading from OCED | PISA 2015. Feel free to follow the links to dig deeper.

The mean score in reading performance is one of the highest among PISA-participating countries and economies. (527 PISA Score, rank 2/69 , 2015) Download Indicator

Boys’ performance in reading is one of the highest among PISA-participating countries and economies. (514 PISA Score, rank 3/69 , 2015) Download Indicator

Girls’ performance in reading is one of the highest among PISA-participating countries and economies. (540 PISA Score, rank 4/69 , 2015) Download Indicator

The percentage of low performers in reading (below proficiency Level 2) is one of the lowest among PISA-participating countries and economies. (10.7 %, rank 66/69 , 2015) Download Indicator

The percentage of top performers in reading (proficiency Level 5 or 6) is one of the highest among PISA-participating countries and economies. (14 %, rank 2/69 , 2015) Download Indicator

The percentage of low-performing boys in reading (below proficiency Level 2) is one of the lowest among PISA-participating countries and economies. (13.9 %, rank 66/69 , 2015) Download Indicator

The percentage of top-performing boys in reading (proficiency Level 5 or 6) is one of the highest among PISA-participating countries and economies. (11.3 %, rank 2/69 , 2015) Download Indicator

The percentage of low-performing girls in reading (below proficiency Level 2) is one of the lowest among PISA-participating countries and economies. (7.5 %, rank 65/69 , 2015) Download Indicator

The percentage of top-performing girls in reading (proficiency Level 5 or 6) is one of the highest among PISA-participating countries and economies. (16.8 %, rank 3/69 , 2015) Download Indicator

Critics of large-scale assessment see things quite a bit differently, however. Teachers and teachers’ unions have argued that the many advantages often associated with large-scale assessment are rarely supported by research (Covaleskie 2002). Many argue that the millions of dollars spent on these assessments should be re-invested directly into classrooms, where it is much more likely to have a positive impact (English Teachers Federation of Ontario 2001). Moreover, they argue that many of the disadvantages of these tests are overlooked. Many of the skills that are fostered by teachers in the classroom, such as creativity, are not measured by large-scale assessments. Many factors impact on how students do in such test situations, including socioeconomic background, immigrant status, and parental education (Willms 1999). Raw scores from such tests ignore how these and other factors influence how students do on the assessments, instead shifting the blame to teachers. The outcomes of tests also fail to take into consideration that many schools and classrooms are greatly under-resourced. Poor test scores may be attributable to this lack of resources experienced by many teachers.

Because their students’ outcomes on such tests are often interpreted as reflections on their teaching skills and efforts, teachers feel pressured by administrators and are therefore likely to participate in what is known as teaching to the test. This approach focuses on teaching materials similar to those found on upcoming assessments—rather than engaging in innovative pedagogical ways to deliver curriculum.13 Teaching to the test also weakens teacher morale and job satisfaction (Volante 2004). Critics argue that in addition to acting as a negative form of social control over teachers, these assessments also can actually act to harm the self-esteem and mental health of children by placing an enormous amount of stress upon them (Hartley-Brewer 2001).

Alberta, which has the most extensive assessment systems in the country, also has the lowest percentage of high school graduates progressing into post-secondary institutions. Critics such as the Alberta Teachers’ Association (2005) have suggested that this is a direct consequence of such heavy reliance on high-stakes testing and test scores (Volante 2007). A summary of the arguments for and against large-scale assessments can be found in Table 5.2. See Box 5.4 for a discussion of large-scale assessment controversies that have entered recent news.

|

Table 5.2 Summary of Arguments For and Against Large-Scale Assessment |

|

|

Advocates of LSA |

Critics of LSA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Source: Adapted from Volante 2006:7–8. | |

Box 5.4 – In the News: Recent Backlashes against Assessment Exercises

In January 2009, the Vancouver school board approved a letter to be sent to parents that instructed them on how to have their children voluntarily excluded from the Foundation Skills Assessment exams (issued in Grades 4 and 7). The B.C. Teachers’ Federation vehemently opposes the Foundation Skills Assessment exams, arguing that the tests neither help the children learn nor help the teachers teach. They also argue that the test results do not provide parents with any useful feedback about their children’s progress and that the assessments use a great deal of resources (they are very expensive to administer) that would be better used in directly funding schools. The move by the school board was admonished by the Education Minister, who indicated that these are not optional exams. In previous years, the B.C. Teachers’ Federation has taken out full-page ads in the Vancouver Sun explaining to parents how they could prevent their children from taking the exams.

In Ontario there was an increase in “cheating and irregularities” in 2010 reported by the Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO). The EQAO is an independent agency funded by the Ontario government which oversees province-wide testing. Ten Ontario schools were investigated by EQAO for breaking testing procedures by photocopying previous years’ tests, allowing unauthorized resource materials (i.e., dictionaries, calculators) to be used, revealing questions beforehand, or making hand gestures to students about which answers on the tests were correct. The EQAO was alerted to possible cheating and inadvertent breaking of rules by concerned parents and school officials. In the past, teachers and principals have been suspended when cheating has been established. The EQAO has stated that it plans to add a “checklist” for teachers that includes clearer instructions on how to administer the tests.

Hidden Curriculum

The content of textbooks from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries across Canada had a not-so-hidden message of trying to create a certain type of citizen. That citizen would not question the existing class system, would be loyal to the British Empire, and would uphold Christian values. The delivery of a “moral education” was a strong underlying assumption of educational practices of the time, which is very consistent with what Durkheim (Chapter 2) argued to be the fundamental objective of education.

The changes that have occurred in curriculum over the past several decades have been shaped by various forces. Early on, approaches were used to keep British Imperial culture front and centre so as to avoid the Americanization of the curriculum. In the 1960s and afterward, awareness about the importance of diversity and non-British perspectives were highlighted, with curricular practices changing to accommodate a wider range of perspectives. Other topics highlighted in this chapter so far have shown that education is contested territory. Particular groups oppose the inclusion of certain works of literature and topics (around evolutionary theory and discussions of sexuality) in the classroom because it contradicts what they believe and therefore what they think their children should learn.

Curriculum also develops uniquely in various jurisdictions due to their socio-historical specificity. Raptis and Baxter (2006), for example, note how mathematic curriculum developed differently in British Columbia and Quebec. British Columbia was far more influenced by American educational theorists than Quebec, exhibiting major differences that can be traced back to the mid-1800s. For example, mathematics curriculum in Quebec is focused heavily on mental calculations and developing mental automaticity for multiplication by 10, 100, and 1000. Quebec mathematics curriculum is also more unified, with a focus on conceptual understanding and “problem solving,” which refers to the pedagogical practice of demonstrating the relationship of new material to previously learned material and emphasis of the conceptual understanding of mathematical principles. In British Columbia, the curriculum exhibited a different teaching approach that required students to respond to focused and direct questions such as determining the percentage of a number. Problem solving, in contrast, was treated as a separate topic. Raptis and Baxter (2006) argue that these differences in curriculum are deeply ingrained in the socio-historical development of each province, with practices in Quebec resembling educational approaches from France (which emphasize intellectual development) and British Columbia being more influenced by American educational theorists, which favours a “socially utilitarian” curriculum.

The differences between American and French approaches can been explained by the different histories that each educational system had followed. The American educational system developed to educate and assimilate a growing immigrant population in the New World. The development of the education system in France began much earlier and was greatly shaped by Napoleon in order to train personnel to administer his empire. French education was modernized in the late nineteenth century, when public school became free, mandatory, and secular for children less than 15 years of age. France was not an immigrant-receiving country in the way that the United States (and Canada) were, and therefore the content of the curriculum is not as focused on “assimilation,” as the population at the time was relatively homogenous.

Multicultural Curriculum

Canada is a country with a diverse population. The official policy of multiculturalism was introduced in 1971 by the Trudeau government and the Multicultural Act, passed in 1988, further guaranteed cultural diversity to Canadians, allowing them to preserve and share their unique cultural heritages. While the founding immigrant groups of Canada were British and French, immigration to Canada after the World Wars resulted in a population that was much more diverse than simply English, French, and Aboriginal. The purpose of the multiculturalism policy was to legitimize the place of the various ethno-cultural groups in Canada. One of the objectives of this policy was to celebrate this diversity of ethno-cultural groups and their contributions to Canadian society. Another was to promote healthy relationships between and among these groups (Ghosh 2004).

Stages of Multicultural Education in Canada

Ghosh (2004) identifies five stages of the development of multicultural education in a Canadian context. The first is the assimilation stage. Until the adoption of the official policy of multiculturalism, assimilation into an Anglo-dominated culture was expected in English Canada. Differences from the dominant culture were seen as deficiencies that needed to be remedied. The next stage is referred to as the adaptation stage, which characterized the practices in education observed shortly after multiculturalism policy was introduced in Canada in the 1970s. Ghosh notes that in this stage, cultural differences were regarded as “exotic.” Attention to multicultural topics and cultural diversity was approached with a “museum view”: practices specific to particular ethnicities were regarded as romantic cultural artifacts. Sometimes known as the “saris, samosas and steel drums” approach, these first attempts at introducing multiculturalism into education largely failed at fostering integration and tolerance because non-dominant cultures were regarded as strange and exotic and associated only with specific foods, dances, and music.

The third stage of multicultural education in Canada is known as the accommodation stage. In this stage, attention shifted to promoting equality of opportunity. This was represented in education by the introduction of topics like ethnic studies, heritage language programs, and the inclusion of gender and ethnic representation in curricula. According to Ghosh (2004), this was realized through a variety of techniques, including removing ethnic and racial stereotypes from curriculum material, hiring minority teachers, and offering heritage-language courses in schools. Ghosh argues, however, that despite these efforts, the overall Eurocentric content of the curriculum and culture of the education system continued to marginalize ethnic minority students and discriminate against them in both overt and covert ways.

The fourth stage of multicultural education is called incorporation. In this stage, attention has shifted to promoting intergroup relations. Within education, this has meant the hiring of more teachers from ethno-cultural groups and the implementation of prejudice-reduction strategies. In this stage, attempts are made at creating alliances between different groups.

The fifth stage is referred to as the integration stage, which Ghosh notes is a “radical departure” from the previous stages. In this stage, world views are altogether different. Instead of a Eurocentric White cultural framework as the dominant world view, the orientation at this stage is much more global. Teachers using a critical race pedagogy focused on anti-racist education are characteristic of multicultural education in Canada at this stage. This approach to pedagogy in Canada, however, has been used in only a handful of cities and provinces, and usually on an experimental basis (Ghosh 2004).

How Successful Has Implementing a Multicultural Curriculum Been?

Like any other curricular reform, the success of multiculturalism in curriculum hinges on how well the topic is covered in teacher training. Failure to educate teachers on how to adopt reformed curriculum will often result in failed reform efforts (Lemisko and Clausen 2006).

Dunn et al. (2009) investigated how teacher education programs approached the topic of multicultural education, and found that most student teachers had very little experience with cultural and ethnic diversity. This led to feelings of anxiety about their ability to work in diverse classroom environments. While many student teachers indicated that they were open-minded, many also expressed some resistance to acquiring intercultural competence, or being able to successfully teach and communicate with students from other cultures. Dunn explains that teachers may feel that students should learn how to assimilate into their classrooms.

Bickmore (2006), in an examination of curriculum documents from Manitoba, Nova Scotia, and Ontario, found that ideals of multiculturalism were pervasive in learning outcomes but that diversity is often represented as harmonious and conflict is regarded as minimal. There are few presentations of critical viewpoints. Historical injustices are often discussed as though they have been resolved or are nearly resolved. Bickmore argues that this can be confusing, particularly for students who are racialized and have had very different experiences of what is being discussed. Bickmore notes that “citizenship education that begins by marginalizing conflicting voices is unlikely to provide a solid foundation for more pluralistic democracy” and that these types of curricular practices are emphasizing assimilation more than democratic engagement. They act as a form of “implicit social control and homogenization through [the] inculcation of unproblematized values, silencing, or marginalization of dissenting viewpoints” (p. 382).

Across Canada, the implementation of multiculturalism into education varies considerably. One way that multiculturalism is promoted is through the teaching of heritage languages. Teaching of languages other than French and English expanded in schools across the country from the 1980s onwards. Table 5.3 summarizes the current offerings by province and territory, although the language offerings at any particular school would be reflected by the needs of a particular area. A large number of heritage languages are offered in British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario. None are offered in New Brunswick, Newfoundland, or Prince Edward Island, likely reflecting that these areas have seen less immigrant settlement than other parts of Canada. More recently, many provinces (and all the territories) have offered instruction in Aboriginal languages. Most, but not all, language instruction is offered from the kindergarten to Grade 12 levels, although this varies by province.

Quebec has not adopted multicultural education practices like the rest of the country. Because Quebec is interested in protecting its distinct society status and the French language, the language of instruction in Quebec schools is mandated to be French (although English school boards exist as well). Because Quebec also had (and continues to have) a large influx of immigrants, integrating different cultural groups was also regarded as necessary. Instead of multiculturalism, however, a policy of intercultural education was promoted. This means that Quebec schools will be pluralistic in their outlook, but that French will be relied upon as the language of instruction. Multiculturalism as a federal policy is fundamentally in ideological opposition to French-Quebecois nationalism (Ghosh 2004), and Quebec has been opposed to it since its inception in the late 1980s. It was believed that multiculturalism would erode Quebeckers’ autonomy and their linguistic culture (Talbani 1993). Policies and procedures associated with intercultural education have the goal of assimilating non-francophone students into Quebec linguistic and cultural practices. As explained by Talbani, “Quebec government addressed the issue of the cultural diversity by defining its priorities based on two factors: (1) controlling the selection of immigrants in response to the specific economic and cultural needs of Quebec society; and (2) the harmonious integration of new-comers of all origins with the French-speaking community” (1993:411, citing Quebec 1990).

Table 5.3 Heritage Language Courses Offered in the Provinces and Territories

| Province | Territory | Language | Notes |

| British Columbia | American Sign Language

German Italian Japanese Korean Mandarin Chinese Punjabi Spanish First People’s Languages |

Implemented 1998 to present, all K-12 |

| Alberta | First Nations, Metis, and Inuit (FNMI) languages programs

Blackfoot and Cree offered at elementary, junior, and senior high Chinese German Italian Japanese Latin Punjabi Spanish Ukrainian |

Implemented from the outcomes of the Western Canadian Protocol Aboriginal Languages Curriculum Framework (2000), which began in 1997 as a joint effort between educators in the western provinces and Aboriginal communities to achieve the goal of creating a suitable Aboriginal languages curriculum.

Most available K-12 |

| Saskatchewan | FIrst Nations and Metis languages

Ukrainian |

In place since 1994

Available K-12 |

| Manitoba | Aboriginal languages

American Sign Language (ASL) German Hebrew Spanish Ukrainian

|

Aboriginal languages in place since 2007 and available K-12

ASL since 1993 Other heritage languages available to begin at Grade 1, 4, 7 or Senior 1 |

| Ontario | Native languages | |

| Classical languages | ||

| Numerous international languages | In curriculum since 1999 for Native languages and offered from Grade 1

Classical and international languages offered from Grade 9 Numerous international and classical languages have been on offer since the Heritage Language Program began in Ontario in the late 1980s |

|

| Quebec | Spanish

Cree |

Spanish offered as a third language after French and English starting at beginning of Cycle II

Cree School Board created in Northern Quebec via the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (1975) |

| New Brunswick | None | |

| Nova Scotia | Mi’kmaw | Miigmao language

Gaelic Spanish German |

Mi’kmaw | Miigmao implemented in 2003 and offered from Grade 1 onward

Gaelic instituted in 1997 and offered from Grade 10 onward |

| Newfoundland | none | |

| Prince Edward Island | none | |

| Yukon | Aboriginal languages | Often used as second language of instruction from Kindergarten onward |

| Nunavut | Inuktitut | Curriculum embedded in “Inuuqatigiit” which is a curriculum based on Inuit perspectives and implemented from Kindergarten onward |

| Northwest Territories | Aboriginal languages | Curriculum embedded in “Inuuqatigiit” which is a curriculum based on Inuit perspectives and implemented from Kindergarten to Grade 6 |

Canada’s Aboriginals and Curriculum

St. Denis (2007) has argued that Aboriginal students have been subjected to processes of racialization that have “historically, legally and politically” divided Aboriginal communities. Many critics such as Aikenhead (2006) have argued that school curriculum in Canada has prioritized a Western European scientific way of knowing. This way of knowing is so engrained and taken-for-granted in Western culture that it can be difficult to promote alternative viewpoints. This Western way of knowing tends to emphasize positivism and an ontology of objective reality (Chapter 2), particularly when it comes to science. However, there are other ways of knowing that do not value these particular orientations. As argued by Aikenhead, the Aboriginal way of knowing includes an “alternative notion of knowledge as action and wisdom, which combines the ontology of spirituality with holistic, relational, empirical practices in order to celebrate an ideology of harmony with nature for survival” (p. 387).

Teaching styles in the Canadian classroom are typically task-focused and rely on linear thinking and passive learning (or the idea that students are “banks”, discussed in Chapter 2). Teaching is based on conveying small units of information rather than on aiming for an understanding of the whole (Cherubini, Hodson, Manley-Casimir, and Muir 2010; Ghosh 2002). These practices are at odds with the Indigenous way of knowing. Critics argue that the Canadian school system has not nurtured Aboriginal students’ identities by recognizing their ways of knowing, which alienates students and makes them less inclined to want to participate in learning (Aikenhead 2006; Canadian Council on Learning 2007a; Carr 2008; Cherubini, Hodson, Manley-Casimir, and Muir 2010). Aikenhead (2006) calls this forcing of Eurocentric views on Aboriginal students, and the resulting delegitimization of their ways of knowing, cognitive imperialism. Many teachers, however, are not trained to deal with Aboriginal ways of knowing, as it is largely absent from teacher training practices across Canada—with some notable exceptions, such as Brock University’s specialized degree in Aboriginal Education (Redwing and Hill 2007).

Multicultural Curriculum and White Privilege

Many scholars, including Schick and St. Denis (2005), have argued that the current approaches to multicultural education have originated from a problematic starting point that views Canadian culture as “raceless, benevolent, and innocent” (p. 296). The authors argue that the common ways of talking about multiculturalism fail to acknowledge that privilege—particularly White privilege—vastly improves the likelihood of individuals overcoming disadvantage. In Canadian popular discourse, racism is thought of as something that occurred in the past—or that happens in the United States—and discussions of racism are considered taboo or ill-mannered. Schick and St. Denis argue that is imperative for teachers to recognize that White-skin privilege serves to advantage White students and teachers by allowing them to move with ease in a Eurocentric Western environment. For example, the racism that Aboriginal peoples faced limited their access to and success in education, but these same mechanisms served to assist White students. While such students may regard their success as solely the result of hard work, critical race theorists (Chapter 2) argue that it is necessary to recognize that the system is not as meritocratic as we might believe.