1 Introduction

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to

- Define sociology of education.

- Explain and give examples of what is meant by social structure.

- Explain how understanding news stories about education-related topics can be enhanced by incorporating approaches from the sociology of education.

Introduction to the Sociology of Education

On any given day in Canada, there is likely to be a major news item that features the topic of education. Whether it is about the value of a university degree, the cost of education, the working conditions of teachers, or achievements of students, education is of great concern and interest to policy makers, politicians, and Canadians in general. There is a common belief in Canadian society (and beyond) that education is essential to ensure a good quality of life and that education holds the key to an individual’s success. Parents who hope their children have a better standard of living than they did will more often than not point to education as being the major determining factor in this outcome. This is particularly true if the parents are recent immigrants (Krahn and Taylor 2005), because the parents very likely settled in Canada to improve the prospects of their children. Education, therefore, is regarded as something to be attained in order to ensure future economic security, social status, and perhaps even social and psychological well-being.

In this book, the topic of education is discussed within a sociological framework. The sociology of education is a branch of sociology that studies how social structures affect education as well as the various outcomes of education. Social structures in general refer to enduring patterns of social arrangement. Sociologists see social structure in all aspects of society. For example, social class is a social structure that generally refers to the socioeconomic background of an individual and his or her family. Social class has been found to impact on many aspects of life that are related to education, including educational achievement (i.e., grades), educational attainment (highest qualification), and future aspirations. Other examples of social structures are bureaucracy, legal systems, the family, religion, and race. These are all enduring patterns of social relations that are observable in society—groupings that are entrenched in our collective minds and that guide our behaviours and shape our life outcomes.

The sociology of education is a way of examining education in order to understand how social structures shape various aspects of education. Indeed, these social structures shape not only how we understand education, but also how it has been designed over the years, how the structure of education systems exists today, and the various outcomes associated with educational credentials.

A Case Study of a Major Education-Related News Item in Canada

It is perhaps most useful to introduce the topic of sociology of education by using a recent case study that received much national and international attention. After giving details of this case, various approaches from the sociology of education can be used to further understand the events. On February 27, 2012, a motion calling for the equal funding of First Nations education was passed unanimously in the House of Commons.1 This means that the members of the House of Commons agreed that schools on First Nations reserves should be given the same kinds of resources as “regular” schools that are found throughout the rest of the country. This news made headlines across Canada.

But why is this a major historic landmark for First Nations education? It may seem like a very reasonable request to many—something that should not have to be asked for, but is already assumed to be in place.2 In order to understand the significance of this decision, it is necessary to have more information about some of the events that led one particular member of Parliament to introduce the motion in the first place.

Attawapiskat First Nation

Much of the recent discussion about poor living conditions in First Nations communities has been a result of attention given to circumstances at the Attawapiskat First Nation, an isolated fly-in community located in the James Bay region of Northern Ontario. This community is home to the Muskego James Bay Cree and has a population of around 3500, although in 2012 just over half of all members lived on the reserve, with the remainder living off site.3 Much of the year, the reserve is inaccessible by ground transportation. In the winter months, “ice roads” serve as a means of travelling into and out of the community.

In October 2011, Chief of Attawapiskat First Nation Theresa Spence declared a state of emergency. This state of emergency was called due to a housing crisis faced by the community and the fast approach of winter. Some families were living in non-insulated tents and sheds with no electricity or running water. The Canadian Red Cross mobilized in late November to assist in the housing crisis. A period of over one month passed before the Red Cross stepped in—because, in the meantime, provincial and federal governments were debating responsibility for the community, and in the process accomplishing little to improve the circumstances of those in makeshift housing and sub-zero temperatures.

This was not, however, the first time a state of emergency had been declared in Attawapiskat. In fact, it was the third time in as many years. The first declaration of emergency was made in April 2009, when site demolition of a school closed years earlier due to a massive diesel leak on the land released the strong odour of diesel fumes into the air. The community closed its two schools due to an air quality crisis and requested evacuation. The federal government did not support an evacuation and asked instead to monitor air quality in the area. In July 2009, according to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, “soil sampling and testing is completed. Continuous air quality monitoring is implemented. Both demolition sites (the former elementary school and the old water treatment plant) are capped with clay soil to prevent odours, vapours, and water accumulation.”4

The second declaration of emergency occurred a few months later in July of the same year, when a massive sewage flood dumped waste into eight homes in the community. Those affected by the flooding (about 90 people) were evacuated by the community and placed in off-reserve accommodation for several weeks. The provincial and federal governments again did not consider these circumstances to warrant evacuation.

Many people probably did not hear of the first and second declarations of emergency at Attawapiskat, but they very likely are aware of the situation that unfolded in late 2011. What changed? Local officials and the member of Parliament for the area, Charlie Angus, started a major publicity campaign, which included numerous news conferences, letters, and a YouTube video.5 People started to pay attention after the media gave the issue considerable coverage. Photographs of the decrepit and overcrowded housing conditions were revealed, showing residents living in tents and other temporary accommodations (often called “third world” in the media), often without plumbing or proper heating

systems, resulting in not only national but international outcry.6

Attawapiskat First Nation and School Facilities

The above discussion details three recent major crises at the Attawapiskat First Nation. But these particular crises occurred in tandem with another major issue that has left the community without a permanent school for more than 12 years. The community had been waiting to have a new school built after the old one (built in 1976) was closed in 2000 due to site contamination. Concerns about contamination of the land upon which the school sat began shortly after the school was built. In 1979, thousands of litres of oil leaked into the soil near the school, and in 1982, evidence was found of oil in the school foundation and petroleum fumes in the classrooms. In the mid-1980s, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) investigated the complaints and recommended a cleanup of the area. Still, over 10 years later, more environmental investigations into the site revealed a high level of contamination of harmful toxins requiring immediate action.7 Additional site testing in 2000 revealed again that the school was sitting above highly toxic land, with soil readings of various chemicals that were well beyond safe levels for humans. Throughout the two decades of site contamination, students and teachers continued to attend class at this school despite the strong chemical odours and numerous health-related complaints.

The school was officially closed permanently in 2000 due to the contamination. INAC then moved the school into temporary portable classrooms beside the contaminated site. Children had to attend classes in these portables, which were placed on contaminated brownfields (i.e., land previously used for industrial purposes).8 These same portables were still in use at the time of writing (2012) to accommodate over 400 elementary school children in the community. See Box 1.1 for a description of the temporary school.

Numerous plans by the federal government to build a new school have since failed to materialize. Three successive INAC ministers (Robert Nault, Andy Scott, and Jim Prentice) have promised, and then reneged on, a new school for the community. Plans to build a new school in 2008 were cancelled, with Chuck Strahl, minister for Indian Affairs and Northern Development, indicating that there were more pressing projects elsewhere to fund.9 Frustrated by the ongoing delay in replacing their school, teenagers and adults in Attawapiskat began a campaign to raise awareness of their situation in the rest of Canada and the world.

Box 1.1 – A Decade-Old “Temporary” School

Linda Goyette, reporting for Canadian Geographic in 2010, provides an account of the decade-old “temporary” school in Attawapiskat.

“As Shannen Koostachin used to say, this place is not a real school. Eleven rough buildings stand in a narrow strip between the fenced contamination site and an airstrip. In poor condition, the gloomy structures do not resemble anything you could describe as a school.

“I arrived at recess time. Kids poured out of the squat classrooms to play tag, kick a ball or climb up on a fire hydrant to play King of the Castle. This barren yard is their playground—no swings, no slides, no monkey bars, no baseball diamond or soccer field. In deepest winter, students pull on parkas, snow pants and boots to walk to the community centre for phys. ed. Their school has no gym.

“There is no library, no cafeteria, no art room, no music room. There are no heated corridors between the scattered classrooms. Every day, children and teachers walk inside and outside—inside and outside, inside and outside—through blizzards, ice fog, sleet and thunderstorms. Maintenance workers move a rough wooden ramp to a different portable every year to allow access to a disabled student as he moves through the grades.”10

Source: Still Waiting in Attawapiskat, by Linda Goyette, Canadian Geographic magazine, Dec 2010. Used with permission of the author.

Shannen Koostachin

Shannen Koostachin was a well-known teen activist from Attawapiskat who became the face of the Attawapiskat School Campaign. Koostachin and her classmates decided to fight back against the federal government’s failure to deliver the promised school in 2008 after Chuck Strahl’s announcement, using social media such as YouTube and Facebook. They began a campaign that they called “Education Is a Human Right,” calling for “safe and comfy” schools with quality, culturally based education for First Nations students. The campaign developed momentum and received national attention and support from teachers and students from across the country. Shannen Koostachin, while only 13 years old, spoke at a rally on Parliament Hill in 2008 and met with INAC minister Chuck Strahl to ask him why no school had been built. Koostachin also spoke at numerous rallies and youth conferences and was nominated for an International Children’s Peace Prize. The movement created by her and her friends and supporters is considered to be the largest children’s rights movement in the history of Canada.

Shannen and her sister attended high school off the reserve, making the decision to leave the fly-in community and move to Temiskaming Shores, Ontario—500 kilometres from Attawapiskat. This decision was based on her and her family’s belief that quality high school education could be attained only outside of their community and off-reserve. Tragically, Shannen was killed in a car accident in May of 2010 at age 15.

Shannen’s friends and family, as well as MP Charlie Angus, rallied together in order to carry on Shannen’s vision of equal education for First Nations children and youth, calling this campaign “Shannen’s Dream.” Shannen’s work was focused on raising awareness about the lack of a school in Attawapiskat and the series of broken promises made by federal ministers to the community. She and her supporters believed in equal educational opportunities for all Canadians.

Charlie Angus, the New Democratic Party member of Parliament representing Timmins–James Bay (Ontario), introduced Motion 571 as a private member’s bill into the House of Commons on September 17, 2010. Motion 571 is also known as Shannen’s Dream, after Shannen Koostachin. It read:

“That, in the opinion of the House, the government should:

- declare that all First Nation children have an equal right to high quality culturally-relevant education;

- commit to provide the necessary financial and policy supports for First Nations education systems;

- provide funding that will put reserve schools on par with non-reserve provincial schools;

- develop transparent methodologies for school construction, operation, maintenance and replacement;

- work collaboratively with First Nation leaders to establish equitable norms and formulas for determining class sizes and for the funding of educational resources, staff salaries, special education services and indigenous language instruction; and

- implement policies to make the First Nation education system, at a minimum, of equal quality to provincial school systems.”11 (From Motion 571, published in the Notice Paper no. 66, September 20, 2010, available at http://www.parl.gc.ca/content/ hoc/House/403/NoticeOrder/066/ordpaper066.PDF. Used with permission of the House of Commons)

The motion was also widely accepted by First Nations communities and many education-related organizations, such as the Canadian School Boards Association,12 the Ontario English Catholic Teachers’ Association,13 and the Canadian Teachers’ Federation.

Despite the motion and the continued momentum of the campaign, the school, which was again promised in late 2010, was in various stages of planning and negotiation. A detailed timeline of events around this time, including meetings between INAC and the community officials, can be found at www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/ 1100100016328.

During the Attawapiskat state of emergency declaration of 2011, the federal government appointed a controversial “third-party manager” to handle the band’s finances—to the outcry of band officials, as the gesture suggested to the band that they were not capable or trustworthy enough to manage their federal funds.

Angus reintroduced the motion again (now referred to as Motion 202) in the House of Commons in November 2011. This coincides with the flurry of media attention that was being given to the living conditions on the Attawapiskat First Nation at that time, and rekindled larger public interest in the poor education facilities in the community. The motion was passed unanimously in late February of 2012, meaning that in principle, all voting members of the House of Commons agreed on equal funding of First Nations schools. The federal budget announced on March 29, 2012, by the Conservative government committed $100 million over three years to Aboriginal education, although the same budget allocated $26.9 million in cuts to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada.

On March 6, 2012, Attawapiskat First Nation and the current minister for Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development John Duncan announced that a construction contract had been awarded to a Manitoba firm (along with artist renderings) for the new school, which is expected to open for the 2013–2014 school year.14

Using the Sociology of Education to Help Understand the Events in Attawapiskat

The above description of recent events at Attawapiskat First Nation has been an attempt at summarizing a series of crises experienced by the First Nation over the last several decades. There are many details missing, and a thorough historical overview of the crises would warrant its own separate book. The objective of this brief summary, however, is to demonstrate that understanding education-related issues, such as the ones in Attawapiskat, can be greatly aided by the use of sociological approaches.

There are many questions that may emerge from the above discussion of the events in Attawapiskat. Motion 571 (later 201) advocating for equal treatment of First Nations students may seem to be an odd request, for example. Why would they not be treated equally in the first place? Why would it take so long for a school to be built? Why are the living conditions in that First Nation so substandard? There are no easy answers to these important questions, but there are sociological arguments that can be made about what larger social structures and histories have contributed to the current situation.

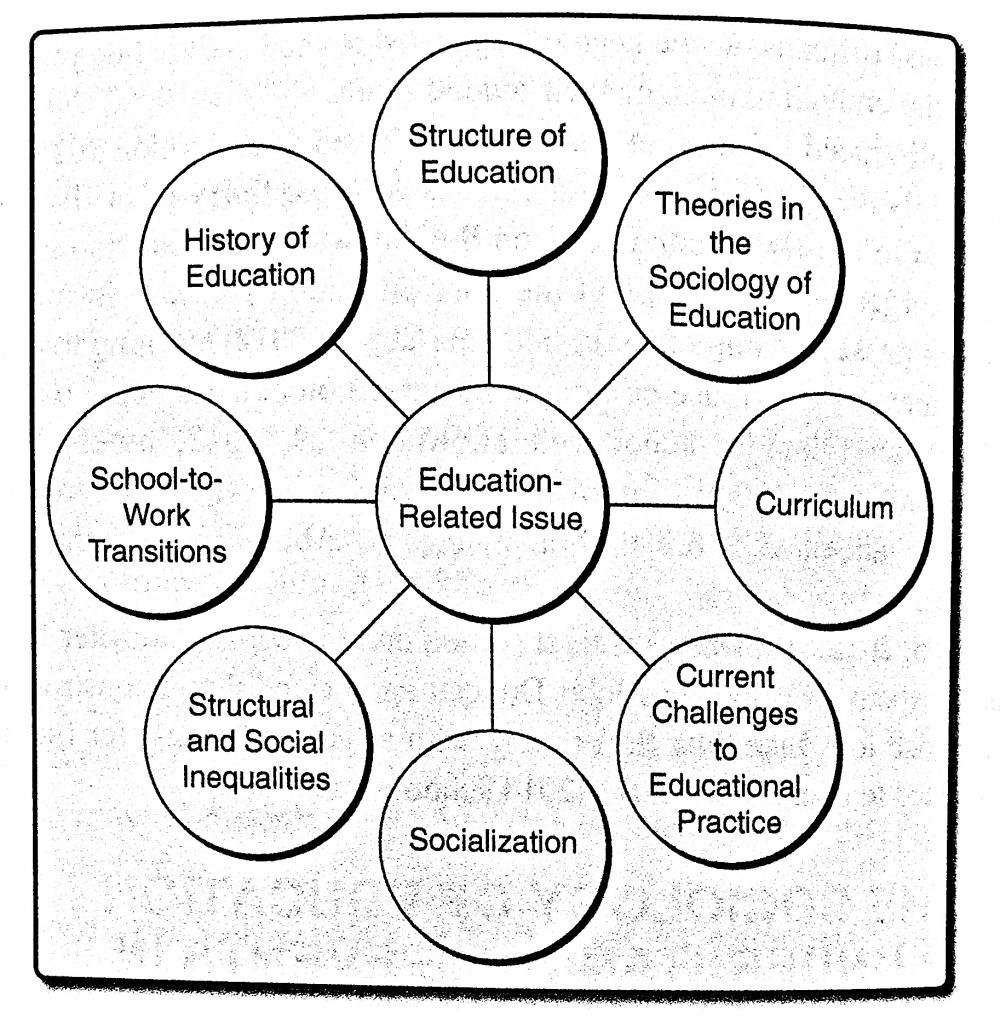

Each successive chapter of this book is divided into a topic area within the sociology of education that can be applied to many different topics within the expansive area of education (see Figure 1.1). This textbook is divided into eight additional substantive chapters, which all focus on different aspects of the sociology of education.

In Chapter 2, various theoretical approaches to the sociology of education are considered. The discipline of sociology is strongly anchored by theory and the methodological foundations of research practice. Chapter 2 is an important exploration of various sociological theories that can be used to understand topics in education in Canada and beyond. The chapter begins with the traditional macro-sociological approaches offered by Karl Marx, Max Weber, and Émile Durkheim, and moves into various more contemporary theories in the sociology of education.

One particular theory that is discussed in Chapter 2 is critical race theory. This theory understands race to be at the centre of issues of inequality in education. Much more nuanced than straightforward and overt “racism,” critical race theory argues that the racial minority students are often disadvantaged because there is an informal cultural baseline to which they are always being compared. Because “Whiteness” is the dominant cultural and racial group in Canada, norms and expectations associated with “White culture” are considered the norm and any deviations from that are seen at worst as weaknesses and at best as “exotic” characteristics. Critical race theory can perhaps help contextualize some of the cultural frustrations expressed by First Nations officials and representatives of the INAC. Critical race theorists would argue that First Nations priorities in education (which may include culturally relevant curriculum) are “different” from the norm and therefore considered less legitimate and inferior. Critical race theorists may also interpret the prime minister’s decision to intervene with “third-party management” of the Attawapiskat First Nation (during the 2011 crisis) to be indicative of mistrust about the First Nation’s ability to manage its own finances and as an attempt to “repair” the matter by sending an uninvited member of the dominant culture.

In addition to critical race theory, some of the theories of social mobility may also be useful to understand the situation in Attawapiskat. Social mobility theories examine how individuals are able to achieve upward social mobility—or advance their social position. Social mobility theories, however, illustrate that it is difficult for disadvantaged youth to better their situations and that they are more likely to stay in the same social class and economic conditions into which they were born, due to various factors including strong processes of socialization that make movement out of their class of origin rather challenging.

It is not possible to entirely understand educational practices today unless their historical contexts are considered. In Chapter 3, the history of education in Canada is discussed as it developed in different pockets across the country. The history of how Aboriginals were treated in Canada is particularly important to the Attawapiskat case. While the colonization of Canada and resulting mistreatment of Aboriginals is an acknowledged fact in this nation’s history, of particular importance to issues pertaining to education is the historic Indian Act of 1876—a legal document which still dictates how Aboriginal affairs (including education) are structured in Canada. The Indian Act was a piece of legislation that was drawn up after Canada became a nation (1867), in order to articulate the obligations of the Canadian government to First Nations people. At that particular time in the country’s history, the government had allocated First Nations people to specific areas of land (starting the “reservation” system) and had decreed that the First Nations people were wards of the Crown to be taken care of by the federal government, without rights to self-government. Importantly, the act dictated that issues of First Nations education (which at that point in time was entirely concerned with assimilating the “Indians” into British Christian culture) were the responsibility of the federal government. It is important to recognize that this historic Indian Act is still the reason that matters of on-reserve schooling are treated as a concern to be dealt with by federal politicians. For the rest of Canadian students, education is a provincial matter that is shaped by individual policies of each jurisdiction. In terms of the housing crisis in Attawapiskat, housing for on-reserve communities is still a federal issue and it is not possible (legally) for an on-reserve citizen to have a mortgage (i.e., if they want to buy a house, it is not possible unless they have all the funds at hand or go through alternate means of funding).

In Chapter 4, the discussion turns to the structure of education. As noted, on-reserve schools are operated by the federal government. About 20 percent of First Nations (i.e., not including Métis or Inuit) children attend school on reserve in schools managed by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development. Structural changes since the 1970s have meant that more First Nations bands are now somewhat in control of their schools—the amount of control varies according to the First Nation. In the early 1990s, INAC transferred some of the control of the school to Attawapiskat First Nation Education Authority (AFNEA). This sharing of control between federal and local officials has the potential to cause conflict, because although the local band officials have gained control over decisions on hiring and staffing, the federal officials still have control over major spending initiatives, such as building new schools.15 As such, inherent tensions can be seen as being “built in” to the way First Nations are able to control the educational infrastructures in their communities.

In Chapter 5, the focus turns to curriculum. Curriculum encompasses that which is learned in school and comprises the learning objectives for each level of education (grade) and subject. Curricula have changed significantly over time, and these changes are documented in Chapter 5. Also, what is taught also tends to vary across the different jurisdictions of Canada. Despite being under federal jurisdiction, on-reserve schools do not have not an official curriculum. Instead, guidelines indicate that the education quality must be “comparable” to that offered by the provincial jurisdiction. In other words, children at on-reserve schools should be receiving the same quality of education as those in provincially run schools (Mendelson 2008). Pictures of dilapidated schools with scarce resources built on toxic land cast much doubt on the likelihood that comparability targets have been met in such cases.

One major element of the dream that Shannen Koostachin had about First Nations education is that the curriculum of on-reserve students would be culturally relevant and reflect the beliefs and practices of First Nations people. Aboriginal education advocates have argued that typical Canadian curricular practices tend to have a Eurocentric view of the world that is strongly attached to the scientific method. In order to give relevance and legitimacy to the traditional practices in the community, critics argue that Aboriginal “ways of knowing” and cultural practices should be incorporated into the curriculum of on-reserve schools (Aikenhead 2006) and off-reserve schools with substantial Aboriginal students. Many First Nations school boards implement the provincial curriculum and make adjustments to make it more culturally relevant (Mendelson 2008), although Mendelson (2008) notes that the (small) First Nations school boards have an onerous task of organizing all aspects of education (curriculum, funding, hiring, policy development, codes of conduct, etc.) within the First Nation, whereas children in provincially run schools have external policy-makers at the level of the provincial ministry dedicated to curriculum development. Without external levels of curriculum development support, it is difficult to maintain quality and improve performance.

As described by a recent Senate Standing Committee on First Nations Education:

Currently, every First Nation community is left on their own to try to develop and deliver a range of educational services to their students. First Nations schools operate without any statutory recognition and authority to do so. Federal policy to guide efforts in this regard is, at best, ad hoc and piecemeal. The Department requires First Nations to educate their students at levels comparable to provincial and territorial jurisdictions, and yet provides them no meaningful supports by which to do so. No one actually knows who is ultimately accountable for the educational outcomes and services provided to First Nations students. This situation is, quite frankly, incomprehensible. (Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples 2011:56. Senate of Canada. Reproduced with permission.)

No establishment of a Canada-wide plan for First Nations education or development of a consistent system of First Nations education exists. It is also not an insignificant point that many of the parents and grandparents of current First Nations students were subjected to the residential schooling system that forcibly removed First Nations children from their homes at an early age (from around 1930 to the late 1960s) to be placed in boarding schools where they often experienced abuse and humiliation and were made to “unlearn” their First Nations cultures.

Turning to Chapter 6, the discussion moves to socialization in the schooling process. Children and youth spend a great deal of their lives in school, and in addition to their families, schools are agents of socialization that shape them into the persons that they become as adults. Children must learn how to be students—the role that they will have in the class and the appropriate behaviours associated with this role. Students are also socialized into becoming future productive members of society through being taught essential literacy and numeracy skills, and in many jurisdictions renewed attention has been given to including moral education into the curriculum. Socialization is accomplished through many means in the school setting in which they experience their education: the relationship that students have with their teachers and with one another, and the school bond (commitment to one’s school) that they have.

One of the messages that the Attawapiskat School Campaign led by Shannen Koostachin emphasized was the general sense of worth that inadequate schools were giving to young people about themselves as individuals. In a speech, she articulated this very message when she said, “It’s hard to feel pride when our classrooms are cold, when mice run over our lunches. . . . It’s hard to feel you can have the chance to grow up to be somebody important when you don’t have proper resources, like a library.”16 The disadvantaged socialization prospects of young people in this already economically depressed community suffering from a high youth suicide rate were at the heart of the campaign.

In Chapter 7, attention is turned to structural and social inequalities in schooling. Clearly, the Attiwapiskat students in the case considered in this chapter have experienced many structural and social disadvantages in their schooling, most notably in the form of the inadequacy of their school facilities. Larger social inequalities also affect children and others in the area, particularly the high rates of poverty and unemployment that are experienced by individuals living on the Attawapiskat First Nation. As discussed in Chapter 7, socioeconomic status is closely linked to the educational outcomes of children, in which children from poor families do worse at school and have less favourable overall outcomes.

Aboriginal youth in general have strikingly low rates of high school graduation, and this is even more pronounced if they live on reserve. In some remote communities, youth must make the decision to leave their family homes in order to be able to attend high school in a larger community, as many First Nation communities do not have secondary schools. Leaving one’s community and family can be a difficult decision for anyone, particularly a young person. As discussed above, Koostachin and her sister left their First Nation community to attend high school because of their perception that in order to have successes later in life, a superior education had to be sought outside their community. The low educational attainment of Aboriginal youth has enormous ramifications. Without completing secondary education, the employment prospects of youth (Aboriginal or otherwise) are incredibly limited. This results in a continued cycle of poverty that is largely due to structural and social inequalities experienced in early life and exacerbated by limited employment prospects in their communities.

As stated above, education is clearly associated with future life outcomes of individuals, and this is the focus of Chapter 8. The end of formal education is usually followed by a transition into the labour market. Such school-to-work transitions have changed over time in Canada, with youth now spending longer periods of time in formal education. As suggested in the previous paragraph, Aboriginal youth are far more likely to drop out of high school, which severely curtails their employment opportunities. In remote reserves such as Attawapiskat, there are very limited employment opportunities to begin with—with unemployment rates at around 90 percent. The biggest job provider is the Victor diamond mine run by De Beers, which employs about 100 band members. De Beers also worked with Northern College to train workers for the diamond mine. The mine is located on traditional Cree territory. The First Nation does not receive any direct revenues from the mine, although the Province of Ontario does receive tax revenues from the operation.

Chapter 9, the last chapter of this book, is about current challenges to education practices. Various challenges are identified, with particular attention paid to issues that are highly associated with globalization, or the merging of individual country economies into a global market. The global economic crisis is discussed in this chapter, particularly with regard to its ramifications into various areas of people’s lives—including education. It brings issues of government spending into the forefront of government debates. What money is being “wasted” on unnecessary public services? What cuts can be made?

The conditions of economic deprivation in Attawapiskat spurred the Conservative prime minister Stephen Harper to declare that more than $90 million had been given to the community since he had taken office in 2006, and to question how it had been spent. The Conservative government then offered additional monies on the condition that “third-party management” (which would be paid by the band) would be in charge of administering funds. The ideological approach of neoliberalism is also explored in this chapter, particularly in relation to how such approaches contextualize conflicts experienced in education. Neoliberalism is the ideological belief in the reduction of public spending and promotion of reliance on private enterprise within a global economy. The introduction of the third-party management can be interpreted as the federal government’s neoliberal response to the crisis in Attawapiskat.

Neoliberal policies are also reflected in the influence of private enterprise creeping into public institutions. One obvious and ever-increasing example is when advertisers are allowed to promote products within schools. In the case of Attawapiskat, the De Beers company has been running a “Books in Homes” program since 2009 in James Bay, providing around 2000 area children with their school textbooks each year.

Chapter Summary

In this chapter, sociology of education was defined. Social structures were also defined, along with examples of how social structures impact on the sociology of education. The crisis in Attawapiskat First Nation was detailed, with particular attention given to the passing of the Shannen’s Dream motion and how it was a product of the ongoing Attawapiskat School Campaign. The focus of each additional chapter was then introduced, paying particular attention to how concepts from the chapter could give additional insights to the events that have unfolded at the Attawapiskat First Nation in terms of their school crisis as well as their general state of long-term and marked economic disadvantage.

Review Questions

1. Define sociology of education.

2. What is meant by social structure? Give three examples of social structures that may have an impact upon education.

Exercises

- Using Figure 1.1 as a guide, summarize the various dimensions of the sociology of education that are applicable to the Attawapiskat school crisis.

- Look through the headlines of local and national newspapers and identify an education-related topic that is currently being given attention. Summarize the issue. Using the Attawapiskat case study detailed in this chapter as an example, suggest various aspects of the sociology of education that may be useful in understanding the issue you have identified in more detail.

- Using the internet, examine problems that have been identified at other First Nations schools. Some particularly striking examples are found in the cases of the Bunibonibee and Lake St. Martin First Nations. What do these cases have in common with Attawapiskat? How are they different?

Film Recommendation

- Canada: Apartheid Nation (directed by Angela O’Leary)

Key Terms

A branch of sociology that studies how social structures affect education as well as the various outcomes of education.