3.8 What Is the Role of the Context? Contingency Approaches to Leadership

Learning Objectives

- Analyze the major situational conditions that determine the effectiveness of different leadership styles.

- Identify the conditions under which highly task-oriented and highly people-oriented leaders can be successful based on Fiedler’s contingency theory.

- Discuss the main premises of the Path-Goal theory of leadership.

- Describe a method by which leaders can decide how democratic or authoritarian their decision making should be.

What is the best leadership style? By now, you must have realized that this may not the right question to ask. Instead, a better question might be: under which conditions are different leadership styles more effective? After the disappointing results of trait and behavioral approaches, several scholars developed leadership theories that specifically incorporated the role of the environment. Researchers started following a contingency approach to leadership—rather than trying to identify traits or behaviors that would be effective under all conditions, the attention moved toward specifying the situations under which different styles would be effective.

Fiedler’s Contingency Theory

The earliest and one of the most influential contingency theories was developed by Frederick Fiedler (1967). According to the theory, a leader’s style is measured by a scale called Least Preferred Coworker (LPC) scale. People who are filling out this survey are asked to think of a person who is their least preferred coworker. Then, they rate this person in terms of how friendly, nice, and cooperative this person is. Imagine someone you did not enjoy working with. Can you describe this person in positive terms? In other words, if you can say that the person you hated working with was still a nice person, you would have a high LPC score. This means that you have a people-oriented personality and you can separate your liking of a person from your ability to work with that person. However, if you think that the person you hated working with was also someone you did not like on a personal level, you would have a low LPC score. To you, being unable to work with someone would mean that you also dislike that person. In other words, you are a task-oriented person.

According to Fiedler’s theory, different people can be effective in different situations. The LPC score is akin to a personality trait and is not likely to change. Instead, placing the right people in the right situation or changing the situation is important to increase a leader’s effectiveness. The theory predicts that in “favorable” and “unfavorable” situations, a low LPC leader—one who has feelings of dislike for coworkers who are difficult to work with—would be successful. When situational favorableness is medium, a high LPC leader—one who is able to personally like coworkers who are difficult to work with—is more likely to succeed.

How does Fiedler determine whether a situation is favorable, medium, or unfavorable? There are three conditions creating situational favorableness: (1) leader-subordinate relations, (2) position power, and (3) task structure. If the leader has a good relationship with most people, has high position power, and the task is structured, the situation is very favorable. When the leader has low-quality relations with employees, has low position power, and the task is relatively unstructured, the situation is very unfavorable.

Research partially supports the predictions of Fiedler’s contingency theory (Peters et al., 1985; Strube & Garcia, 1981; Vecchio, 1983). Specifically, there is more support for the theory’s predictions about when low LPC leadership should be used, but the part about when high LPC leadership would be more effective received less support. Even though the theory was not supported in its entirety, it is a useful framework to think about when task- versus people-oriented leadership may be more effective. Moreover, the theory is important because of its explicit recognition of the importance of the context of leadership.

Table 3.8.1: Situational Favorableness

| Situation Favorableness | Leader-subordinate Relations | Position Power | Task Structure | Best Style |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Favorable | Good | High | High | Low LPC Leader |

| Good | High | Low | ||

| Good | Low | High | ||

| Medium | Good | Low | Low | High LPC Leader |

| Poor | High | High | ||

| Poor | High | Low | ||

| Poor | Low | High | ||

| Unfavorable | Poor | Low | Low | Low LPC Leader |

(Source: Fiedler, 1967)

Situational Leadership

Another contingency approach to leadership is Kenneth Blanchard and Paul Hersey’s Situational Leadership Theory (SLT) which argues that leaders must use different leadership styles depending on their followers’ development level (Hersey et al., 2007). According to this model, employee readiness (defined as a combination of their competence and commitment levels) is the key factor determining the proper leadership style.

The model summarizes the level of directive and supportive behaviors that leaders may exhibit. The model argues that to be effective, leaders must use the right style of behaviors at the right time in each employee’s development. It is recognized that followers are key to a leader’s success. Employees who are at the earliest stages of developing are seen as being highly committed but with low competence for the tasks. Thus, leaders should be highly directive and less supportive. As the employee becomes more competent, the leader should engage in more coaching behaviors. Supportive behaviors are recommended once the employee is at moderate to high levels of competence. And finally, delegating is the recommended approach for leaders dealing with employees who are both highly committed and highly competent. While the SLT is popular with managers, relatively easy to understand and use, and has endured for decades, research has been mixed in its support of the basic assumptions of the model (Blank et al., 1990; Graeff, 1983; Fernandez & Vecchio, 2002). Therefore, while it can be a useful way to think about matching behaviors to situations, overreliance on this model, at the exclusion of other models, is premature.

Table 3.8.2: Situational Leadership Theory

| Follower Readiness Level | Competence (Low) | Competence (Low) | Competence (Moderate to High) | Competence (High) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commitment (High) | Commitment (Low) | Commitment (Variable) | Commitment (High) | |

| Recommended Leader Style | Directing Behavior | Coaching Behavior | Supporting Behavior | Delegating Behavior |

Situational Leadership Theory helps leaders match their style to follower readiness levels.

Path-Goal Theory of Leadership

Robert House’s path-goal theory of leadership is based on the expectancy theory of motivation (1971). Expectancy theory of motivation suggests that employees are motivated when they believe—or expect—that (1) their effort will lead to high performance, (2) their high performance will be rewarded, and (3) the rewards they will receive are valuable to them. According to the path-goal theory of leadership, the leader’s main job is to make sure that all three of these conditions exist. Thus, leaders will create satisfied and high-performing employees by making sure that employee effort leads to performance, and that their performance is rewarded. The leader removes roadblocks along the way and creates an environment that subordinates find motivational.

The theory also makes specific predictions about what type of leader behavior will be effective under which circumstances (House, 1996; House & Mitchell, 1974). The theory identifies four leadership styles: directive, supportive, participative, and achievement-oriented. Each of these styles can be effective, depending on the characteristics of employees (such as their ability level, preferences, locus of control, achievement motivation) and characteristics of the work environment (such as the level of role ambiguity, the degree of stress present in the environment, the degree to which the tasks are unpleasant).

- Directive leaders provide specific directions to their employees. They lead employees by clarifying role expectations, setting schedules, and making sure that employees know what to do on a given workday. The theory predicts that the directive style will work well when employees are experiencing role ambiguity on the job. If people are unclear about how to go about doing their jobs, giving them specific directions will motivate them. However, if employees already have role clarity, and if they are performing boring, routine, and highly structured jobs, giving them direction does not help. In fact, it may hurt them by creating an even more restricting atmosphere. Directive leadership is also thought to be less effective when employees have high levels of ability. When managing professional employees with high levels of expertise and job-specific knowledge, telling them what to do may create a low empowerment environment, which impairs motivation.

- Supportive leaders provide emotional support to employees. They treat employees well, care about them on a personal level, and are encouraging. Supportive leadership is predicted to be effective when employees are under a lot of stress or when they are performing boring and repetitive jobs. When employees know exactly how to perform their jobs but their jobs are unpleasant, supportive leadership may also be effective.

- Participative leaders make sure that employees are involved in making important decisions. Participative leadership may be more effective when employees have high levels of ability and when the decisions to be made are personally relevant to them. For employees who have a high internal locus of control, or the belief that they can control their own destinies, participative leadership gives employees a way of indirectly controlling organizational decisions, which will be appreciated.

- Achievement-oriented leaders set goals for employees and encourage them to reach their goals. Their style challenges employees and focuses their attention on work-related goals. This style is likely to be effective when employees have both high levels of ability and high levels of achievement motivation.

Table 3.8.3: Predictions of Path-Goal Theory

| Situation | Appropriate Leadership Style |

|---|---|

| When employees have high role ambiguity | Directive |

| When employees have low abilities | |

| When employees have external locus of control | |

| When tasks are boring and repetitive | Supportive |

| When Tasks are stressful | |

| When employees have high abilities | Participative |

| When the decision is relevant to employees | |

| When employees have high internal locus of control | |

| When employees have high abilities | Achievement-oriented |

| When employees have high achievement motivation |

(Information in the table based on House, 1996; House & Mitchell, 1974)

The path-goal theory of leadership has received partial but encouraging levels of support from researchers. Because the theory is highly complicated, it has not been fully and adequately tested (House & Aditya, 1997; Stinson & Johnson, 1975; Wofford & Liska, 1993). The theory’s biggest contribution may be that it highlights the importance of a leader’s ability to change styles, depending on the circumstances. Unlike Fiedler’s contingency theory, in which the leader’s style is assumed to be fixed and only the environment can be changed, House’s path-goal theory underlines the importance of varying one’s style, depending on the situation.

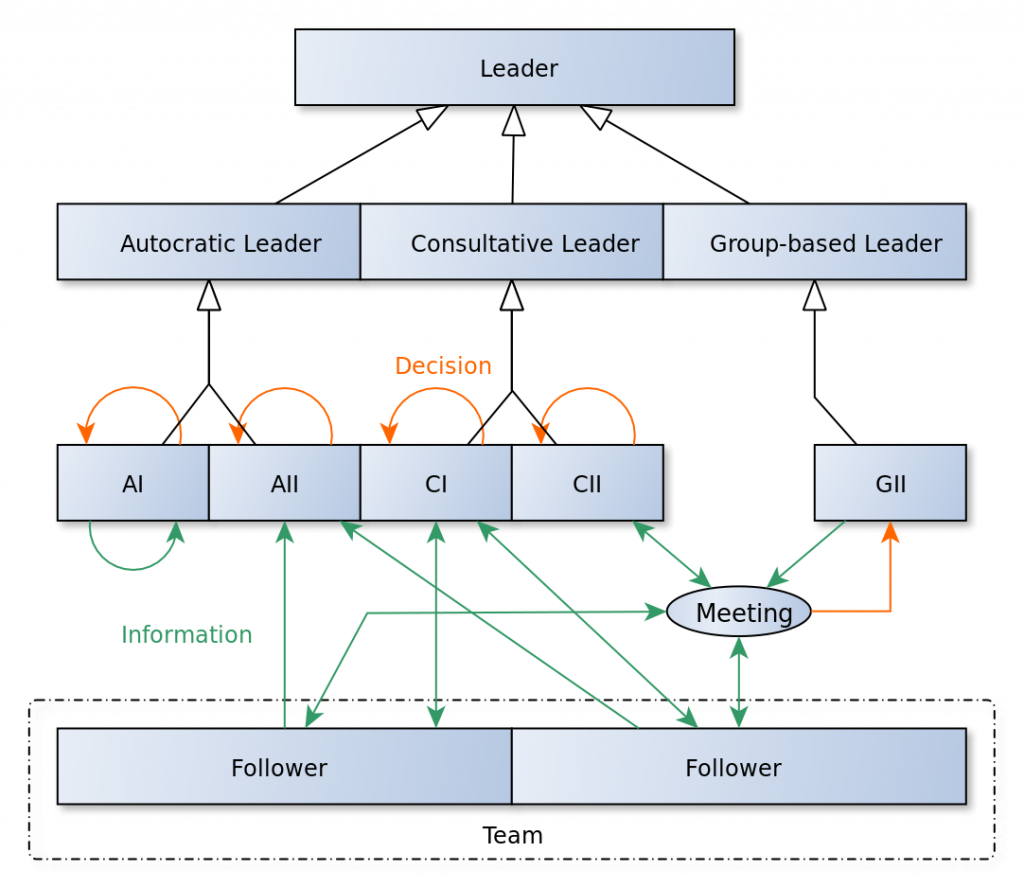

Vroom and Yetton’s Normative Decision Model

Yale School of Management professor Victor Vroom and his colleagues Philip Yetton and Arthur Jago developed a decision-making tool to help leaders determine how much involvement they should seek when making decisions (Vroom, 2000; Vroom & Yetton, 1973; Jago & Vroom, 1980; Vroom & Jago, 1988). The model starts by having leaders answer several key questions and working their way through a funnel based on their responses.

Let’s try it. Imagine that you want to help your employees lower their stress so that you can minimize employee absenteeism. There are a number of approaches you could take to reduce employee stress, such as offering gym memberships, providing employee assistance programs, establishing a nap room, and so forth. Let’s refer to the model and start with the first question. As you answer each question as high (H) or low (L), follow the corresponding path down the funnel.

- Decision significance. The decision has high significance because the approach chosen needs to be effective at reducing employee stress for the insurance premiums to be lowered. In other words, there is a quality requirement to the decision. Follow the path through H.

- Importance of commitment. Does the leader need employee cooperation to implement the decision? In our example, the answer is high, because employees may simply ignore the resources if they do not like them. Follow the path through H.

- Leader expertise. Does the leader have all the information needed to make a high-quality decision? In our example, leader expertise is low. You do not have information regarding what your employees need or what kinds of stress reduction resources they would prefer. Follow the path through L.

- Likelihood of commitment. If the leader makes the decision alone, what is the likelihood that the employees would accept it? Let’s assume that the answer is Low. Based on the leader’s experience with this group, they would likely ignore the decision if the leader makes it alone. Follow the path from L.

- Goal alignment. Are the employee goals aligned with organizational goals? In this instance, employee and organizational goals may be aligned because you both want to ensure that employees are healthier. So let’s say the alignment is high, and follow H.

- Group expertise. Does the group have expertise in this decision-making area? The group in question has little information about which alternatives are costlier or more user-friendly. We’ll say group expertise is low. Follow the path from L.

- Team competence. What is the ability of this particular team to solve the problem? Let’s imagine that this is a new team that just got together and they have little demonstrated expertise to work together effectively. We will answer this as low, or L.

Based on the answers to the questions we gave, the normative approach recommends consulting employees as a group. In other words, the leader may make the decision alone after gathering information from employees and is not advised to delegate the decision to the team or to make the decision alone with no input from the team members.

In Figure 3.8.1, Vroom and Yetton’s leadership decision tree shows leaders which styles will be most effective in different situations.

Leadership Decision Tree

Vroom and Yetton’s model is somewhat complicated, but research results support the validity of the model. On average, leaders using the style recommended by the model tend to make more effective decisions compared with leaders using a style not recommended by the model (Vroom & Jago, 1978).

Cross-Cultural Context

Gabriel Bristol, the CEO of Intelifluence Live, a full-service customer contact center offering affordable inbound customer service, outbound sales, lead generation, and consulting services for small to mid-sized businesses, notes “diversity breeds innovation, which helps businesses achieve goals and tackle new challenges” (Bristol, 2016). Multiculturalism is a new reality as today’s society and workforce become increasingly diverse. This naturally leads to the question “Is there a need for a new and different style of leadership?”

The vast majority of the contemporary scholarship directed toward understanding leaders and the leadership process has been conducted in North America and Western Europe. Westerners have “developed a highly romanticized, heroic view of leadership” (Meindl et al., 1985). Leaders occupy the center stage in organizational life. We use leaders in our attempts to make sense of the performance of our groups, clubs, organizations, and nations. We see them as key to organizational success and profitability, we credit them with organizational competitiveness, and we blame them for organizational failures. At the national level, recall that President Reagan brought down Communism and the Berlin Wall, President Bush won the Gulf War, and President Clinton brought unprecedented economic prosperity to the United States during the 1990s.

This larger-than-life role ascribed to leaders and the Western romance with successful leaders raises the question “How representative is our understanding of leaders and leadership across cultures?” That is, do the results that we have examined in this chapter generalize to other cultures?

Geert Hofstede points out that significant value differences (individualism-collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity-femininity, and time orientation) cut across societies. Thus, leaders of culturally diverse groups will encounter belief and value differences among their followers, as well as in their own leader-member exchanges.

There appears to be a consensus that a universal approach to leadership and leader effectiveness does not exist. Cultural differences work to enhance and diminish the impact of leadership styles on group effectiveness. For example, when leaders empower their followers, the effect on job satisfaction in India has been found to be negative, while in the United States, Poland, and Mexico, the effect is positive (Robert et al., 2000). The existing evidence suggests similarities as well as differences in such areas as the effects of leadership styles, the acceptability of influence attempts, and the closeness and formality of relationships. The distinction between task and relationship-oriented leader behavior, however, does appear to be meaningful across cultures (Dorfman & Roonen, 1991). Leaders whose behaviors reflect support, kindness, and concern for their followers are valued and effective in Western and Asian cultures. Yet it is also clear that democratic, participative, directive and contingent-based rewards and punishment do not produce the same results across cultures. The United States is very different from Brazil, Korea, New Zealand, and Nigeria. The effective practice of leadership necessitates a careful look at, and understanding of, the individual differences brought to the leader-follower relationship by cross-cultural contexts (Dorfman et al. 1997).

Exercises

- Do you believe that the least preferred coworker technique is a valid method of measuring someone’s leadership style? Why or why not?

- Do you believe that leaders can vary their style to demonstrate directive, supportive, achievement-oriented and participative styles with respect to different employees? Or does each leader tend to have a personal style that he or she regularly uses toward all employees?

- What do you see as the limitations of the Vroom-Yetton leadership decision-making approach?

- Which of the leadership theories covered in this section do you think are most useful, and least useful, to practicing managers? Why?

Key Takeaways

“What Is the Role of the Context? Contingency Approaches to Leadership” in Principles of Management by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Situational (Contingency) Approaches to Leadership” in Principles of Management by Open Stax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.