3.6 Who Is a Leader? Trait Approaches to Leadership

Learning Objectives

- Describe the position of trait approaches in the history of leadership studies.

- Explain the traits that are associated with leadership.

- Discuss the limitations of trait approaches to leadership.

Traits of a Successful Leader

Ralph Stogdill, while on the faculty at The Ohio State University, pioneered the trait approach to leadership (Stogdill, 1948; Stogdill, 1974). Scholars taking the trait approach attempted to identify physiological (appearance, height, and weight), demographic (age, education, and socioeconomic background), personality (dominance, self-confidence, and aggressiveness), intellective (intelligence, decisiveness, judgment, and knowledge), task-related (achievement drive, initiative, and persistence), and social characteristics (sociability and cooperativeness) with leader emergence and leader effectiveness. After reviewing several hundred studies of leader traits, Stogdill (1974) described the successful leader in this way:

The [successful] leader is characterized by a strong drive for responsibility and task completion, vigor and persistence in pursuit of goals, venturesomeness and originality in problem-solving, drive to exercise initiative in social situations, self-confidence and sense of personal identity, willingness to accept consequences of decision and action, readiness to absorb interpersonal stress, willingness to tolerate frustration and delay, ability to influence other person’s behavior, and capacity to structure social interaction systems to the purpose at hand (Stogdill, 1948).

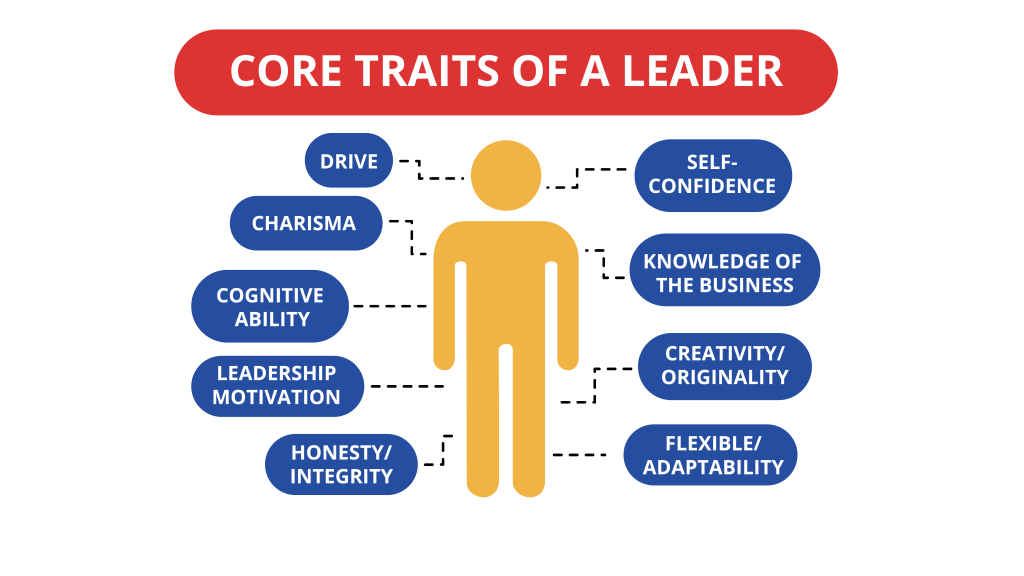

The last three decades of the 20th century witnessed continued exploration of the relationship between traits and both leader emergence and leader effectiveness. Edwin Locke from the University of Maryland and a number of his research associates reviewed the trait research and observed that successful leaders possess a set of core characteristics that are different from those of other people (Kirkpatrick & Locke, 1991; Locke et al., 1991). Although these core traits do not solely determine whether a person will be a leader—or a successful leader—they are seen as preconditions that endow people with leadership potential. Among the core traits identified are:

- Drive—a high level of effort, including a strong desire for achievement as well as high levels of ambition, energy, tenacity, and initiative

- Leadership motivation—an intense desire to lead others

- Honesty and integrity—a commitment to the truth, where word and deed correspond

- Self-confidence—an assurance in one’s self, one’s ideas, and one’s ability

- Cognitive ability—conceptually skilled, capable of exercising good judgment, having strong analytical abilities, possessing the capacity to think strategically and multidimensionally

- Knowledge of the business—a high degree of understanding of the company, industry, and technical matters

- Other traits—charisma, creativity/originality, and flexibility/adaptiveness

(Kirkpatrick & Locke, 1991)

While leaders may be “people with the right stuff,” effective leadership requires more than simply possessing the correct set of motives and traits. Knowledge, skills, ability, vision, strategy, and effective vision implementation are all necessary for the person who has the “right stuff” to realize their leadership potential (Stewart, 1999; Locke et al., 1991). According to Locke, people endowed with these traits engage in behaviors that are associated with leadership. As followers, people are attracted to and inclined to follow individuals who display, for example, honesty and integrity, self-confidence, and the motivation to lead.

With regard to the validity of the “great person approach to leadership”: Evidence accumulated to date does not provide a strong base of support for the notion that leaders are born. Yet, the study of twins at the University of Minnesota leaves open the possibility that part of the answer might be found in our genes. Many personality traits and vocational interests (which might be related to one’s interest in assuming responsibility for others and the motivation to lead) have been found to be related to our “genetic dispositions” as well as to our life experiences (House & Aditya, 1997; Bouchard et al., 1990). Each core trait recently identified by Locke and his associates traces a significant part of its existence to life experiences. Thus, a person is not born with self-confidence. Self-confidence is developed, honesty and integrity are a matter of personal choice, motivation to lead comes from within the individual and is within his control, and knowledge of the business can be acquired. While cognitive ability does in part find its origin in the genes, it still needs to be developed. Finally, drive, as a dispositional trait, may also have a genetic component, but it too can be self- and other-encouraged. It goes without saying that none of these ingredients are acquired overnight.

Other researchers have had success in identifying traits that predict leadership (House & Aditya, 1997); the traits that show relatively strong relations with leadership and overlap with those mentioned by Stogdill are as follows (Judge et al., 2002):

Intelligence

General mental ability, which psychologists refer to as “g” and which is often called IQ in everyday language, has been related to a person’s emerging as a leader within a group. Specifically, people who have high mental abilities are more likely to be viewed as leaders in their environment (House & Aditya, 1997; Ilies et al., 2004; Lord et al., 1986; Taggar et al., 1999). We should caution, though, that intelligence is a positive but modest predictor of leadership. In addition to having a high IQ, effective leaders tend to have high emotional intelligence (EQ). People with high EQ demonstrate a high level of self-awareness, motivation, empathy, and social skills. The psychologist who coined the term emotional intelligence, Daniel Goleman, believes that IQ is a threshold quality: it matters for entry- to high-level management jobs, but once you get there, it no longer helps leaders because most leaders already have a high IQ. According to Goleman, what differentiates effective leaders from ineffective ones becomes their ability to control their own emotions and understand other people’s emotions, their internal motivation, and their social skills (Goleman, 2004). Many observers believe that Carly Fiorina, the ousted CEO of HP, demonstrated high levels of intelligence but low levels of empathy for the people around her, which led to an over-reliance on numbers while ignoring the human cost of her decisions (Karlgaard, 2002).

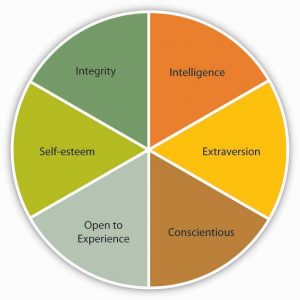

The Big Five Personality Traits

Psychologists have proposed various systems for categorizing the characteristics that make up an individual’s unique personality; one of the most widely accepted is the Big Five model, which rates an individual according to openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Several of the Big Five personality traits have been related to leadership emergence (whether someone is viewed as a leader by others) and leadership effectiveness.

Table 3.6.1: Big Five Personality Traits

| Trait | Description |

|---|---|

| Openness | Being curious, original, intellectual, creative, and open to new ideas. |

| Conscientious | Being organized, systematic, punctual, achievement-oriented, and dependable |

| Extraversion | Being outgoing, talkative, sociable, and enjoying social situations. |

| Agreeableness | Being affable, tolerant, sensitive, trusting, kind, and warm. |

| Neuroticism | Being anxious, irritable, temperamental, and moody. |

(Goldberg, 1990)

For example, extraversion is related to leadership. extraverts are sociable, assertive, and energetic people. They enjoy interacting with others in their environment and demonstrate self-confidence. Because they are both dominant and sociable in their environment, they emerge as leaders in a wide variety of situations.

Out of all personality traits, extraversion has the strongest relationship to both leader emergence and leader effectiveness. Research shows that conscientious people are also more likely to be leaders. This is not to say that all effective leaders are extraverts, but you are more likely to find extraverts in leadership positions. An example of an introverted leader is Jim Buckmaster, the CEO of Craigslist. He is known as an introvert, and he admits to not having meetings because he does not like them (Management Today, 2008).

Steve Ballmer, CEO of Microsoft, is an extraverted leader. For example, to celebrate Microsoft’s 25th anniversary, Ballmer enthusiastically popped out of the anniversary cake to surprise the audience.

Another personality trait related to leadership is conscientiousness. Conscientious people are organized, take initiative, and demonstrate persistence in their endeavors. Conscientious people are more likely to emerge as leaders and be effective as leaders. Finally, people who have openness to experience—those who demonstrate originality, creativity, and are open to trying new things—tend to emerge as leaders and tend to be effective as leaders.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is not one of the Big Five personality traits, but it is an important aspect of one’s personality. The degree to which people are at peace with themselves and have an overall positive assessment of their self-worth and capabilities seems to be relevant to whether they will be viewed as a leader. Leaders with high self-esteem support their subordinates more, and when punishment needs to be administered, they punish more effectively (Atwater et. al., 1998; Niebuhr & Davis, 1984). It is possible that those with high self-esteem have greater levels of self-confidence and this affects their image in the eyes of their followers. Self-esteem may also explain the relationship between some physical attributes and emerging as a leader. For example, research shows a strong relationship between height and being viewed as a leader (as well as one’s career success over life). It is proposed that self-esteem may be the key to the connection of height with leadership because people who are taller are also found to have higher self-esteem and therefore may project greater levels of charisma as well as confidence to their followers (Judge & Cable, 2004).

Integrity

Research also shows that people who are effective as leaders tend to have a moral compass and demonstrate honesty and integrity (Reave, 2005). Leaders whose integrity is questioned lose their trustworthiness, and they hurt their company’s business along the way. For example, when it was revealed that Whole Foods CEO John Mackey was using a pseudonym to make negative comments online about the company’s rival Wild Oats, his actions were heavily criticized, his leadership was questioned, and the company’s reputation was affected (Farrell & Davidson, 2007).

There are also some traits that are negatively related to emerging as a leader and being successful as a leader. For example, agreeable people who are modest, good-natured, and avoid conflict are less likely to be perceived as leaders (Judge et. al., 2002).

The key to benefiting from the findings of trait researchers is to be aware that not all traits are equally effective in predicting leadership potential across all circumstances. Some organizational situations allow leader traits to make a greater difference (House & Aditya, 1997). For example, in small, entrepreneurial organizations where leaders have a lot of leeway to determine their own behavior, the type of traits leaders have may make a difference in leadership potential. In large, bureaucratic, and rule-bound organizations, such as the government and the military, a leader’s traits may have less to do with how the person behaves and whether the person is a successful leader (Judge et. al., 2002). Moreover, some traits become relevant in specific circumstances. For example, bravery is likely to be a key characteristic in military leaders but not necessarily in business leaders. Scholars now conclude that instead of trying to identify a few traits that distinguish leaders from non-leaders, it is important to identify the conditions under which different traits affect a leader’s performance, as well as whether a person emerges as a leader (Hackman & Wageman, 2007).

Other Leader Traits

Sex and gender, disposition, and self-monitoring also play an important role in leader emergence and leader style.

Sex and Gender Role

Much research has gone into understanding the role of sex and gender in leadership (Helgesen, 1990; Fierman, 1990; Rosener, 1990). Two major avenues have been explored: sex and gender roles in relation to leader emergence, and whether style differences exist across the sexes. As noted earlier in this text, the majority of research has been carried out focused on a binary approach to gender (male and female), so does not take into account transgender, non-binary, and other gender identities. It is important to have diverse, equitable, and inclusive organizations. Stereotyping should be avoided. The following research does make some good points to keep in mind, and additional research will be provided as it materializes.

Evidence supports the observation that men emerge as leaders more frequently than women (Chapman, 1975; Fagenson, 1990). Throughout history, few women have been in positions where they could develop or exercise leadership behaviors. In contemporary society, being perceived as experts appears to play an important role in the emergence of women as leaders. Yet, gender role is more predictive than sex. Individuals with “masculine” (for example, assertive, aggressive, competitive, willing to take a stand) as opposed to “feminine” (cheerful, affectionate, sympathetic, gentle) characteristics are more likely to emerge in leadership roles (Kent & Moss, 1994). In our society males are frequently socialized to possess masculine characteristics, while females are more frequently socialized to possess feminine characteristics.

Recent evidence, however, suggests that individuals who are androgynous (that is, who simultaneously possess both masculine and feminine characteristics) are as likely to emerge in leadership roles as individuals with only masculine characteristics. This suggests that possessing feminine qualities does not distract from the attractiveness of the individual as a leader (Kent & Moss, 1994).

With regard to leadership style, researchers have looked to see if male-female differences exist in task and interpersonal styles, and whether or not differences exist in how autocratic or democratic men and women are. The answer is that when it comes to interpersonal versus task orientation, differences between men and women appear to be marginal. Women are somewhat more concerned with meeting the group’s interpersonal needs, while men are somewhat more concerned with meeting the group’s task needs. Big differences emerge in terms of democratic versus autocratic leadership styles. Men tend to be more autocratic or directive, while women are more likely to adopt a more democratic/participative leadership style (Early & Johnson, 1990). In fact, it may be because men are more directive that they are seen as key to goal attainment and they are turned to more often as leaders (Dobbins et al., 1990).

Dispositional Trait

Psychologists often use the terms disposition and mood to describe and differentiate people. Individuals characterized by a positive affective state exhibit a mood that is active, strong, excited, enthusiastic, peppy, and elated. A leader with this mood state exudes an air of confidence and optimism and is seen as enjoying work-related activities.

Recent work conducted at the University of California-Berkeley demonstrates that leaders (managers) with positive affectivity (a positive mood state) tend to be more competent interpersonally, contribute more to group activities, and be able to function more effectively in their leadership role (Staw & Barsade, 1993). Their enthusiasm and high energy levels appear to be infectious, transferring from leader to followers. Thus, such leaders promote group cohesiveness and productivity. This mood state is also associated with low levels of group turnover and is positively associated with followers who engage in acts of good group citizenship (George & Bellenhausen, 1990).

Self-Monitoring

Self-monitoring as a personality trait refers to the strength of an individual’s ability and willingness to read verbal and nonverbal cues and to alter one’s behavior so as to manage the presentation of the self and the images that others form of the individual. “High self-monitors” are particularly astute at reading social cues and regulating their self-presentation to fit a particular situation. “Low self-monitors” are less sensitive to social cues; they may either lack motivation or lack the ability to manage how they come across to others.

Some evidence supports the position that high self-monitors emerge more often as leaders. In addition, they appear to exert more influence on group decisions and initiate more structure than low self-monitors. Perhaps high self-monitors emerge as leaders because in group interaction they are the individuals who attempt to organize the group and provide it with the structure needed to move the group toward goal attainment (Dobbins et al., 1990).

Exercises

- Think of a leader you admire. What traits does this person have? Are they consistent with the traits discussed in this chapter? If not, why is this person effective despite the presence of different traits?

- Can the findings of trait approaches be used to train potential leaders? Which traits seem easier to teach? Which are more stable?

- How can organizations identify future leaders with a given set of traits? Which methods would be useful for this purpose?

- What other traits can you think of that would be relevant to leadership?

Key Takeaways

"Who Is a Leader? Trait Approaches to Leadership" in Principles of Management by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

"The Trait Approch to Leadership" in Principles of Management by Open Stax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.