10.9 How Leaders Can Use Social Networks to Create Value

Learning Objectives

- Analyze how social networks create value.

The Benefits of Social Networks

You probably have an intuitive sense of how and why social networks are valuable for you, personally and professionally. The successful 2008 U.S. presidential campaign of Barack Obama provides a dramatic example of how individuals can benefit when they understand and apply the principles and power of social networking (Cox, 2008). In this section, we discuss three fundamental principles of social network theory, then help you see how social networks create value in your career and within and across organizations, before describing social network analysis (SNA) and making note of some of the ethical implications of SNA.

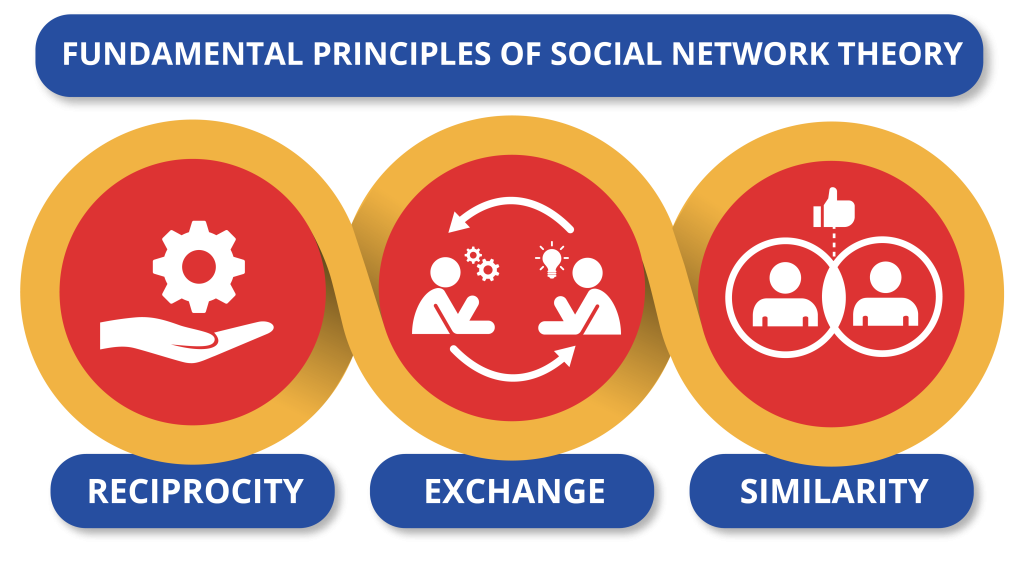

Reciprocity, Exchange, and Similarity

Across all social networks, performance depends on the degree to which three fundamental principles are accounted for (Kilduff & Tsai, 2004). The first is the principle of reciprocity, which simply refers to the degree to which you trade favors with others. With the principle of reciprocity, leaders have the ability to get things done by providing services to others in exchange for the services they require. For instance, you are more likely to get assistance with a problem from a colleague at work when you have helped him or her out in the past. Although the quid pro quo may not be immediate, over time leaders will receive only in proportion to what they give. Unless the exchanges are roughly equivalent over time, hard feelings or distrust will result. In organizations, few transactions are one-shot deals. Most are ongoing trades of “favors.” Therefore, two outcomes are important: success in achieving the objective and success in improving the relationship such that the next exchange will be more productive.

The second principle is the principle of exchange. Like the reciprocity principle, it refers to “trading favors,” but it is different in this way: the principle of exchange proposes that there may be greater opportunity for trading favors when the actors are different from one another. In fact, according to network theory, “difference” is what makes network ties useful in that such difference increases the likelihood that each party brings a complementary resource to the table. Going back to our example where you sought out assistance from a colleague, you probably needed that assistance because that person brought a different skill set, knowledge, or other resources to bear on the problem. That is, since you were different, the value of exchange was greater.

The third principle is the principle of similarity. Psychologists studying human behavior have observed that relationships, and therefore network ties, tend to develop spontaneously between people with common backgrounds, values, and interests. Similarity, the extent that your network is composed only of like-minded folks, also makes it more likely that an individual may be dependent on a handful of people with common interests.

Why is it important to understand these three principles? As a leader, you will find your network useful to the extent that you can balance the effects of the three principles. Because of similarity, it is easier to build networks with those with whom you have various things in common, though this similarity makes the network less useful if you need new ideas or other resources not in the current group. A critical mistake is to become overly dependent on one person or on only a few network relationships. Not only can those relationships sour but also the leader’s usefulness to others depends critically on his or her other connections. Those people most likely to be attractive potential protégés, for example, will also be likely to have alternative contacts and sponsors available to them.

Similarity also means that you have to work harder to build strong exchange networks since their formation is not spontaneous. Most personal networks are highly clustered—that is, your friends are likely to be friends with one another as well. And, if you made those friends by introducing yourself to them, the chances are high that their experiences and perspectives echo your own. Because ideas generated within this type of network circulate among the same people with shared views, a potential winner can wither away and die if no one in the group has what it takes to bring that idea to fruition. But what if someone within that cluster knows someone else who belongs to a whole different group? That connection, formed by an information broker, can expose your idea to a new world, filled with fresh opportunities for success. Diversity makes the difference.

Finally, for reciprocity to work, you have to be willing and able to trade or reciprocate favors, and this means that you might need access to other people or resources outside the current network. For example, you may have to build relationships with other individuals such that you can use them to help you contribute to your existing network ties. We will look more at personal social networks in the next section.

Making Invisible Work Visible

In 2002, researchers Rob Cross, Steve Borghatti, and Andrew Parker published the results of their study of the social networking characteristics of 23 Fortune 500 firms (Cross et. al., 2002). These researchers were concerned that traditional analysis of organizational structure might miss the true way that critical work was being done in modern firms—that is, they theorized that social networks, and not the structure presented on the organization chart, might be a better indicator of the flow of knowledge, information, and other vital strategic resources in the organization. One goal of their research was to better define scenarios in which conducting a social network analysis would likely yield sufficient benefit to justify the investment of time and energy on the part of the organization.

Cross and colleagues found that SNA was particularly valuable as a diagnostic tool for managers attempting to promote collaboration and knowledge sharing in important networks. Specifically, they found SNA uniquely effective in:

- Promoting effective collaboration within a strategically important group.

- Supporting critical junctures in networks that have cross-functional, hierarchical, or geographic boundaries.

- Ensuring integration within groups following strategic restructuring initiatives.

Connect and Develop

Consumer product giant Procter & Gamble (P&G) pioneered the idea of connect and develop, which refers to developing new products and services through a vast social network spanning parts of P&G and many other external organizations. Like many companies, P&G historically relied on internal capabilities and those of a network of trusted suppliers to invent, develop, and deliver new products and services to the market. It did not actively seek to connect with potential external partners. Similarly, the P&G products, technologies, and ‘know-how’, it developed were used almost solely for the manufacture and sale of P&G’s core products. Beyond this, P&G seldom licensed them to other companies.

However, around 2003, P&G woke up to the fact that, in the areas in which it does business, there are millions of scientists, engineers, and other companies globally. Why not collaborate with them? P&G now embraces open innovation, and it calls this approach “Connect + Develop.” It even has a website with Connect + Develop as its address (http://www.pgconnectdevelop.com). This open innovation network at P&G works both ways—inbound and outbound—and encompasses everything from trademarks to packaging, marketing models to engineering, and business services to design.

On the inbound side, P&G is aggressively looking for solutions for its needs, but also will consider any innovation—packaging, design, marketing models, research methods, engineering, and technology—that would improve its products and services. On the outbound side, P&G has a number of assets available for license: trademarks, technologies, engineering solutions, business services, market research methods, and models, and more.

As of 2005, P&G’s Connect + Develop strategy had already resulted in more than 1,000 active agreements. Types of innovations vary widely, as do the sources and business models. P&G is interested in all types of high-quality, on-strategy business partners, from individual inventors or entrepreneurs to smaller companies and those listed in the FORTUNE 500—even competitors. Inbound or out, know-how or new products, examples of success are as diverse as P&G’s product categories. Some of these stories are shown in “P&G Connect + Develop Success Stories.”

Example: P&G Connect + Develop Success Stories

Bringing Technology Into P&G: Olay Regenerist

A few years ago, the folks in P&G’s skin care organization were looking both internally and externally for antiwrinkle technology options for next-generation Olay products. At a technical conference in Europe, P&G first learned of a new peptide technology that wound up being a key component used in the blockbuster product, Olay Regenerist. The technology was developed by a small cosmetics company in France. They not only developed the peptide but also the in vitro and clinical data that convinced P&G to evaluate this material. After they shared some of their work at a conference attended by P&G’s skin-care researchers, they accepted an invitation for their technologists to visit P&G and present their entire set of data on the antiwrinkle effects of the new peptide. This company now continues to collaborate with P&G on new technology upstream identification and further upstream P&G projects.

Taking Technology Out of P&G: Calsura

Not all calcium is created equal.

When P&G was in the juice business, it discovered Calsura, a more absorbable calcium that helps build stronger bones faster, and keeps them stronger for life. The addition of Calsura calcium makes any food or drink a great source of the daily calcium needed for building stronger bones faster in kids, and keeping bones stronger throughout adulthood; Calsura is proven to be 30% more absorbable than regular calcium. Today, P&G licenses the Calsura technology to several companies.

- University Collaboration

- University of Cincinnati Live Well Collaborative

- Collaborating with a university in a new way

P&G has partnered with the prestigious design school at the University of Cincinnati to develop products specifically for consumers over age 50. Using design labs, university students and P&G researchers collaborate to study the unique needs of the over-50 consumer. The goal is to develop and commercialize products that are designed for this consumer bracket.

(Proctor & Gamble, n.d.)

Ethical Implications

Social networks are a key ingredient in the “organizing” component of management, so should in fact help managers lead their organizations to bigger and better things (Borgatti & Molina, 2003; Borgatti & Molina, 2005). So what harm can there be if a leader uses SNA to uncover the invisible structure in their organization? Three top ethical concerns are (1) violation of privacy, (2) psychological harm, and (3) harm to individual standing.

The Ethical Argument in Favor of Managing Social Networks

Being sensitive to the ethical issues surrounding the management of social networks does not mean leaving social network relationships to chance. For instance, if you know that your department would be more productive if person A and person B were connected, as a leader wouldn’t you want to make that connection happen? In many firms, individuals are paid based on performance, so this connection might not only increase the department’s performance but its personal income as well.

The broader issue is that social networks exist and that the social capital they provide is an important and powerful vehicle for getting work done. That means that the ethical leader should not neglect them. Wayne Baker, the author of Achieving Success Through Social Capital (2000), puts it this way:

“The ethics of social capital [i.e., social network relationships] requires that we all recognize our moral duty to consciously manage relationships. No one can evade this duty—not managing relationships is managing them. The only choice is how to manage networks of relationships. To be an effective networker, we can’t directly pursue the benefits of networks or focus on what we can get from our networks. In practice, using social capital means putting our networks into action and service for others. The great paradox is that by contributing to others, you are helped in return, often far in excess of what anyone would expect or predict”.

Exercises

What do the social network concepts of reciprocity, exchange, and similarity mean, and what are their pros and cons?

How do social networks create value in an organizational setting?

What are some ways that an organization can manage the social network to be more innovative?

What is social network analysis?

Why should leaders be concerned about the ethical implications of social network analysis?

Why might it be unethical for leaders to neglect the organization’s social networks?

Key Takeaways

This section showed how social networks create value and goes on to address social network analysis (SNA). We started by introducing the social network theory concepts of reciprocity, exchange, and similarity. We outlined how social networks create value in and across organizations, with specific examples of making invisible work visible before describing SNA and highlighting some of the ethical implications surrounding privacy, harm to individual standing, and psychological harm. Some specific approaches to managing SNA-related ethical issues were outlined as well as the negative ethical implications of ignoring an organization’s SNA.

To foster creativity, 3M encourages technical staff members to spend up to 15% of their time on projects of their own choosing. Also known as the “bootlegging” policy, the 15% rule has been the catalyst for some of 3M’s most famous products, such as Scotch Tape and—of course—Post-it notes (3M, 2002).

“How Managers Can Use Social Networks to Create Value” and “Ethical Considerations With Social Network Analysis” in Principles of Management by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.