10.10 Personal, Operational, and Strategic Networks

Learning Objectives

- Determine the actions required to take to develop a network.

Three Types of Networking

Strong, useful networks don’t just happen at the water cooler. They have to be carefully constructed. What separates successful leaders from the rest of the pack? Networking, as defined in Section 10.8, is creating a fabric of personal contacts to provide the support, feedback, and resources needed to get things done. Yet many leaders avoid networking. Some think they don’t have time for it. Others disdain it as manipulative. To succeed as a leader, Ibarra recommends building three types of networks:

- Personal—kindred spirits outside your organization who can help you with personal advancement.

- Operational—people you need to accomplish your assigned, routine tasks.

- Strategic—people outside your control who will enable you to reach key organizational objectives.

Table 10.10.1: Personal, Operational, and Strategic Networks

| The purpose of this network is to… | If you want to find network members, try… | |

|---|---|---|

| Personal network | exchange important referrals and needed outside information; develop professional skills through coaching and mentoring | participating in alumni groups, clubs, professional associations, and personal interest communities. |

| Operational network | get your work done, and get it done efficiently. | identifying individuals who can block or support a project. |

| Strategic network | figure out future priorities and challenges; get stakeholder support for them. | identifying lateral and vertical relationships with other functional and business unit managers—people outside your immediate control—who can help you determine how your role and contribution fit into the overall picture. |

Making It Happen

Networks create value, but networking takes real work. Beyond that obvious point, accept that networking is one of the most important requirements of a leadership role. To overcome any qualms about it, identify a person you respect who networks effectively and ethically. Observe how he or she uses networks to accomplish goals. You probably will also have to reallocate your time. This means becoming a master at the art of delegation, to liberate time you can then spend on cultivating networks.

Building a network obviously means that you need to establish connections. Create reasons for interacting with people outside your function or organization; for instance, by taking advantage of social interests to set the stage for addressing strategic concerns. Ibarra and Hunter found that personal networking will not help a manager through the leadership transition unless he or she learns how to bring those connections to bear on organizational strategy. In “Guy Kawasaki’s Guide to Networking through LinkedIn,” you are introduced to a number of network growth strategies using that powerful Web-based tool.

Finally, remind yourself that networking requires you to apply the principle of reciprocity. That is, give and take continually—though a useful mantra in networking is “give, give, give.” Don’t wait until you really need something bad to ask for a favor from a network member. Instead, take every opportunity to give to—and receive from—people in your networks, regardless of whether you need help.

Remember, Mark Zuckerberg, cofounder of Facebook, helped to bring social networking to 90 million users.

Social Networks and Careers

We owe our knowledge about the relationship between social network characteristics and finding a job to Stanford sociologist Mark Granovetter. In a groundbreaking study, Granovetter found that job seekers are more likely to find a job through weak ties than through strong ties (Granovetter, 1974). He demonstrated that while job hunters use social connections to find work, they don’t use close friends. Rather, survey respondents said they found jobs through acquaintances: old college friends, former colleagues, people they saw only occasionally or just happened to run into at the right moment. New information, about jobs or anything else, rarely comes from your close friends, because they tend to know the same things and people you do. Strong ties, as you might expect, exist among individuals who know one another well and engage in relatively frequent, ongoing resource exchanges. Weak ties, in contrast, exist among individuals who know one another, at least by reputation, but who do not engage in a regular exchange of resources. In fact, Granovetter showed that those who relied on weak ties to get a job fared better in the market in terms of higher pay, higher occupational status, greater job satisfaction, and longer job tenure. While much in the world has changed since Granovetter’s 1974 research, subsequent studies continue to affirm his basic findings on the consequences of social network structure (Goleman, 2006). As you might expect, for weak ties to be effective though, there must be some basis for the affinity between the indirectly connected individuals, but this affinity can simply be having the same birth month or high school or college alma mater.

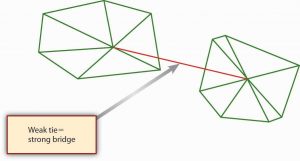

The value of weak ties is highly counterintuitive; we tend to think of relationships being more valuable when we have strong ties to others. However, if you think about it, and as shown in Figure 10.10.3, the value of a weak tie lies in the fact that it is typically a bridging tie, that is, a tie that provides nonredundant information and resources. In the case of a job search, the weak tie serves as a strong bridge. “Social Networking as a Career-Building Strategy” suggests some personal strategies you might consider with your own social networks. Remember to use LinkedIn wisely to find a job – or to have a job find you!

Example: Guy Kawasaki’s Guide to Networking Through LinkedIn

LinkedIn (http://www.Linkedin.com) is the top business social networking site. With more than 30 million members by the end of 2008, its membership dwarfs that of the second-largest business networking site, Plaxo. LinkedIn is an online network of experienced professionals from around the world representing 150 industries (LinkedIn, 2008). Yet, it’s still a tool that is underutilized, so entrepreneur Guy Kawasaki compiled a list of ways to increase the value of LinkedIn (Guy Kawaski, 2008). Some of Kawasaki’s key points are summarized here that can help you develop the strategic side of your social network (though it will help you with job searches as well):

- Increase your visibility: By adding connections, you increase the likelihood that people will see your profile first when they’re searching for someone to hire or do business with. In addition to appearing at the top of search results, people would much rather work with people who their friends know and trust.

- Improve your connectability: Most new users put only their current company in their profile. By doing so, they severely limit their ability to connect with people. You should fill out your profile like it’s a resume, so include past companies, education, affiliations, and activities. You can also include a link to your profile as part of an e-mail signature. The added benefit is that the link enables people to see all your credentials.

- Perform blind, “reverse,” and company reference checks: Use LinkedIn’s reference check tool to input a company name and the years the person worked at the company to search for references. Your search will find the people who worked at the company during the same time period. Since references provided by a candidate will generally be glowing, this is a good way to get more balanced data.

- Make your interview go more smoothly: You can use LinkedIn to find the people that you’re meeting. Knowing that you went to the same school, play hockey, or share acquaintances is a lot better than an awkward silence after, “I’m doing fine, thank you.”

- Gauge the health of a company: Perform an advanced search for the company name and uncheck the “Current Companies Only” box. This will enable you to scrutinize the rate of turnover and whether key people are abandoning ship. Former employees usually give more candid opinions about a company’s prospects than someone who’s still on board.

Exercises

- What characterizes a personal social network and how can they benefit you?

- What characterizes an operational social network?

- What characterizes a strategic social network?

- How do social networks create value in a career management setting?

Key Takeaways

In this section, you were introduced to a different slant on social networks—a slant that helps you manage your networks based on where you might be in an organization. Personal networks are important and tend to follow you everywhere, operational networks are those that help you get your immediate work done, and strategic networks involve a much broader stakeholder group that typically involve individuals who are out of your direct control. We further discussed using social networks as a vehicle for advancing your own career. One key takeaway from this section is that effective leaders are effective networkers, and you will need to figure out the style of networking that works for you as you move higher in an organization.

“Personal, Operational, and Strategic Networks” in Principles of Management by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.