Day 1: Agenda and Resources

Active Learning Techniques (or how to get students doing stuff)

Item number three in Chickering and Gamson’s (1987) “Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education” is the practice of encouraging active learning. After all, “learning is not a spectator sport”! Think about it, when do your students learn best? Or when, as a student, did you learn best. We’re willing to bet that while there were moments when your prof had you simply listening to them that you did learn some, but learning “took off” when you did stuff. Indeed, we learn by doing and students demonstrate their learning in observable ways. This is the reason behind writing learning outcomes in public and observable ways. Naively, the answer to the question about what we want for our students at the end of a course, module, lesson is often stated as “I want my students to know such-and-such” or “I want my students to understand the concept of X.” While many of us can agree to this, the challenge begins when we try to answer the question, How do I know my students know such-and-such?

This brings us to the point that what we usually do, as teachers, is to get our students to do something. Some examples would be to get them to titrate in a Chemistry class, dissect in Biology, write an argument in Philosophy, or carry out a critical inquiry in a Women’s and Gender Study course. The point is, we try to get our students to do things as if they were practitioners of our discipline. Let’s take this a bit further, imagine you were taking a class on how to use a word processor. Furthermore, imagine that the prof taught the course simply by talking at you. One day the prof comes in and says:

Class, today we will learn how to italicize text in our word processor. One way to do this is to click on Format before you need the italics text, clicks on Font style, and from the drop down menu choose Italics. and don’t forget to do the same thing when you want to stop italicizing. Is everyone with me?

Ok, you might be lucky, though, and have remembered to make sure the ribbon is on. Remember that from three weeks ago? If you don’t look at your notes or ask someone if they know how to do that. So, where was I, Oh yes, at the spot where you are typing, you can simply click on the icon with a slanted ‘I’ — this stands for italics. Now start typing and everything should be slanted. When you wish to stop, click that slanted ‘I’ icon and voila, “Bob’s your uncle.” Do y’all think you can remember that? What some of you are a little hesitant? Oh, I see, what happens if you can’t remember? That’s simple. If you forget to start italicizing from the point where you are typing, don’t worry, simply go to the text you wish to italicize, highlight it, and use one of the two methods I just explained to you. Great, that should get you going now in adding accent to your text.

Let’s move on, now we will learn how to generate numbered lists, so that you can create your bibliography. This is why I wanted you to learn italics first. Ok, so this is how you do it …

You can see from this example that there is a good chance that not all the students, if any, will walk away confident they “know” how to italicize. True, the prof taught it, but can we have confidence that the students learned it? How could we improve on the prof’s teaching? Simply by getting the students to DO. Remember it is hard to learn how to play a harp simply by reading the instructions, or balancing a chemical reaction simply by hearing someone tell you how they do it. So, if learning is not a spectator sport, but rather simply a sport, then the teaching involves getting our students to be athletes in this sport.

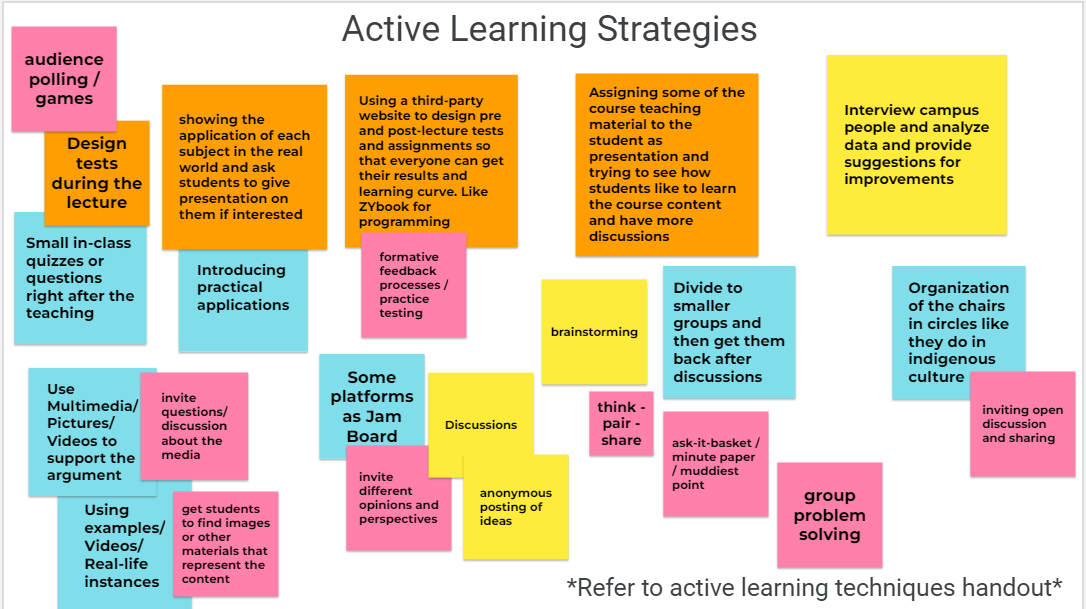

How can you incorporate active learning into your classroom?

From UWindsor’s CTL: Adapted from https://edtech.mst.edu/media/informationtechnology/edtech/documents/teach/02_Active%20Learning%20Continuum.pdf

Clarification Pauses

This simple technique fosters “active listening.” Throughout a lecture, particularly after stating an important point or defining a key concept, stop presenting and allow students time to think about the information. Ask students to review their notes and ask questions about what they’ve written so far.

Designing Effective Questions

Intentionally design questions in advance. http://cll.mcmaster.ca/resources/pdf/Rasmussen.pdf

Writing Activities such as the “Minute Paper”

At an appropriate point in the lecture, ask the students to take out a blank sheet of paper. Then, state the topic or question you want students to address. For example, “Today, we discussed emancipation and equal rights. List as many key events and figures as you can remember. You have two minutes – go!”

Self-Assessment

Students receive a quiz (typically ungraded) or a checklist of ideas to determine their understanding of the subject. Concept inventories or similar tools may be used at the beginning of a semester or the chapter to help students identify misconceptions.

Large-Group Discussion

Students discuss a topic in class based on a reading, video, or problem. The instructor may prepare a list of questions to facilitate the discussion.

Think-Pair-Share

Have students work individually on a problem or reflect on a passage. Students then compare their responses with a partner and synthesize a joint solution to share with the entire class.

Cooperative Groups in Class (Informal Groups, Triad Groups, etc.)

Pose a question for each cooperative group while you circulate around the room answering questions, asking further questions, and keeping the groups on task. After allowing time for group discussion, ask students to share their discussion points with the rest of the class.

Peer Review

Students are asked to complete an individual homework assignment or short paper. On the day the assignment is due, students submit one copy to the instructor to be graded and one copy to their partner. Each student then takes their partner’s work and, depending on the nature of the assignment, gives critical feedback, and corrects mistakes in content and/or grammar.

Group Evaluations

Similar to peer review, students may evaluate group presentations or documents to assess the quality of the content and delivery of information.

Brainstorming

Introduce a topic or problem and then ask for student input. Give students a minute to write down their ideas, and then record them on the board. An example for an introductory political science class would be, “As a member of the minority in Congress, what options are available to you to block a piece of legislation?”

Case Studies

Use real-life stories that describe what happened to a community, family, school, industry, or individual to prompt students to integrate their classroom knowledge with their knowledge of real-world situations, actions, and consequences.

Hands-on Technology

Students use technology such as simulation programs to get a deeper understanding of course concepts. For instance, students might use simulation software to design a simple device or use a statistical package for regression analysis.

Interactive Lecture

Instructor breaks up the lecture at least once per class for an activity that lets all students work directly with the material. Students might observe and interpret features of images, interpret graphs, make calculation and estimates, etc.

Active Review Sessions (Games or Simulations)

The instructor poses questions and the students work on them in groups or individually. Students are asked to show their responses to the class and discuss any differences.

Role Playing

Here students are asked to “act out” a part or a position to get a better idea of the concepts and theories being discussed. Roleplaying exercises can range from the simple to the complex.

Jigsaw Discussion

In this technique, a general topic is divided into smaller, interrelated pieces (e.g., a puzzle is divided into pieces). Each member of a team is assigned to read and become an expert on a different topic. After each person has become an expert on their piece of the puzzle, they teach the other team members about that puzzle piece. Finally, after each person has finished teaching, the puzzle has been reassembled, and everyone on the team knows something important about every piece of the puzzle.

Inquiry Learning

Students use an investigative process to discover concepts for themselves. After the instructor identifies an idea or concept for mastery, a question is posed that asks students to make observations, pose hypotheses, and speculate on conclusions. Then students share their thoughts and tie the activity back to the main idea/concept.

Forum Theater

Use theater to depict a situation and then have students enter into the sketch to act out possible solutions. Students watching a sketch on dysfunctional teams, might brainstorm possible suggestions for how to improve the team environment. Ask for volunteers to act out the updated scene.

Experiential Learning

Plan site visits that allow students to see and experience applications of theories and concepts discussed in the class.

https://www.uwindsor.ca/ctl/492/active-learning-and-lesson-planning

https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/speaking-listening-techniques/

Media Attributions

- Jamboard-ActiveLearning