Module 1: Designing for connection

1.2 Virtual learning contexts and virtual learners

Key principles: Virtual learning contexts

Since the winter of 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the world, many instructors and learners have been teaching and learning in various virtual learning contexts, which include

- fully online courses, which were thoughtfully developed before and during the pandemic and will persist even as more learners return to campuses around the world;

- remote courses, which were developed (in many cases quite quickly) in response to institutional classroom closures due to the pandemic. Some of these courses will continue being offered online, even as learners start to return to the classroom; and

- blended courses (hybrid courses), which involve some blend of online learning components and in-person classroom activities, which are typically focused on active learning, problem-solving, hands-on application, and interactions that are more difficult to do asynchronously or virtually.

One thing that many instructors and learners are craving and missing is the human and social connection that has been interrupted in their academic, work, and social lives. There are many ways to enhance virtual learning experiences, for both instructors and learners, to help them feel more connected, engaged, and included. Before we launch into these, let’s take a moment to think about our virtual learners, what is unique to the virtual learning context, and what we hope virtual learning will look like post-pandemic.

Note

The COVID-19 pandemic marked a significant point in history for most of us and had a huge impact on virtual learning in higher education, resulting in many lessons learned and some that we are still learning. One of the biggest growth areas that came from the challenges of this time is greater awareness, understanding, and interest in humanizing learning and the importance of institutions, instructors, and learners in growing all of our capacities to support mental health and wellness, equity, and inclusivity in virtual teaching in higher education. Now that most instructors and learners have experienced virtual education, there is incredible buy-in to build capacity in delivering courses in a more flexible way. Many welcome a more fully online or blended future in education, but would like to see it done right—with humans front and centre of the experience.

Key principles: Characteristics of your virtual learners

While online and blended courses have been widely available at many universities and colleges around the world for over a decade, the number of online and blended course offerings significantly increased in the few years prior to the pandemic. The pandemic accelerated that growth drastically, as just about all learners experienced learning in virtual contexts while at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there are some important differences to keep in mind about virtual teaching in a pandemic, relative to virtual teaching before and after the pandemic:

- The pandemic was a period marked by a lot of anxiety and uncertainty for many, and isolation, loss, and trauma for some.

- Most instructors, academic support unit (ASU) staff, and learners had not planned for the pivot to virtual teaching and felt underprepared and overwhelmed.

- Many of us did not really choose to work, learn, and/or teach in these virtual contexts, but we did our best to rise to the challenges.

During the pandemic, most learners became virtual learners and with little choice in the matter; post-pandemic, learners have regained their agency, and with it, we’ll see the re-emergence of self-selection patterns. These patterns may mirror those of pre-pandemic times, in terms of who tended to select virtual learning contexts. For instance, research has shown that online learners typically

- chose the online format for its flexibility (Bolliger & Martindale, 2004; Braun, 2008; Troop et al., 2020),

- tend to be slightly older more mature learners ranging from about 25–50 years old (Moore & Kearskey, 2005),

- bring rich life experiences to the virtual classroom (Bostin & Ice, 2011; O’Shea et al., 2015), and

- have more commitments outside the classroom such as busy work schedules or family responsibilities, which can pose challenges to them (Greenland & Moore, 2014).

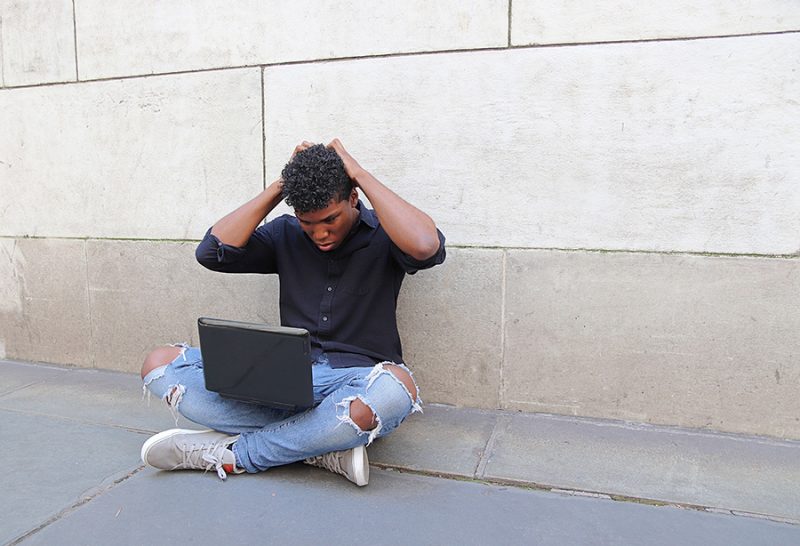

© JohnnyGreig/E+/ Getty Images (Copyrighted image. Do not copy, modify, or redistribute).

The pandemic shed light on and fed into some of the challenges in virtual learning, but as a result, people working in higher education have a greater awareness of the issues, tools, strategies, and resources to help mitigate some of these challenges.

This diversity in the virtual classroom can be a beautiful thing, but accommodating so many different learners, learning from home (which is not a safe or quiet place for all learners), across many time zones, with technology and bandwidth limitations has brought to the foreground some of the barriers that virtual learners face, which are often tied to and compounded by social and economic inequities. Understanding that these issues may be at play, to varying extents, for many of your learners is the first step towards mitigating the negative impact these can have on learning through your course design.

© RenysView/iStock/Getty Images (Copyrighted image. Do not copy, modify, or redistribute).

Reflect and apply: Getting to know your learners

When designing your course, including content, interactions, activities, and assessments, it is important to understand who your learners are.

Can you answer the following questions about your learners?

How to complete this activity and save your work:

Type your response to the question in the box below. Your answers will be saved as you move forward to the next question (note: your answers will not be saved if you navigate away from this page). Your responses are private and cannot be seen by anyone else.

When you complete the below activity and wish to download your responses or if you prefer to work in a Word document offline, please follow the steps below:

- Navigate through all tabs or jump ahead by selecting the “Export” tab in the left-hand navigation.

- Hit the “Export document” button.

- Hit the “Export” button in the top right navigation.

To delete your answers simply refresh the page or move to the next page in this course.

For more information on how to use surveys to get to know your learners see the Strategies in action section in 1.4 Learner–Instructor Connection: Designing Courses With Personality called “Getting to Know Your Learners with Surveys.”

Virtual learning requires a greater degree of self-regulation, self-motivation, metacognition, and self-direction from learners (Brown, 1997; Tsay et al., 2000; Khiat, 2015; Kırmızı, 2015; Johnson, 2015) and not all learners and instructors realize how difficult this aspect of online learning can be. There are, however, many design and facilitation strategies that have a big impact on learner motivation, persistence, metacognition, and academic outcomes and success in virtual learning contexts (Muilenburg & Berge, 2005; Jaggars & Xu, 2016).

Before we get into some high impact design strategies to help build authentic connection and learning, let’s take a closer look at a few of the big challenges and affordances of virtual learning.

Key principles: Challenges and affordances of virtual learning

Some instructors, teaching assistants (TAs), and learners thrive in the virtual teaching and learning environment, appreciating some of the affordances that virtual learning offers, such as the enhanced flexibility of providing content and interactions asynchronously, which can give both instructors and learners additional time to prepare, engage, process, integrate, and reflect. While others find virtual teaching and learning to be a lonely space, missing face-to-face interactions, and frustrated by struggles related to and requirements to learn many different technologies and tools. Instructors, TAs, preceptors, and learners can experience access challenges resulting from bandwidth limitations in different regions, which segregates learners based on geographical location and social-economic status (SES). The most significant access barriers occur during synchronous learning, interactions, and assessments.

Definitions

Asynchronous includes formats that are not live. Learners can interact with content, assessments, instructors, and peers in their own time, rather than at a specific time. Asynchronous design typically still includes deadlines, but learners are given a window of time.

Synchronous includes live formats. Learners are required to interact with content, assessments, and/or facilitators, and peers at a specific set time.

Source: Fostering Engagement: Facilitating Courses in Higher Education

The following table provides a summary of some of the challenges and affordances or benefits of synchronous and asynchronous approaches to

- course content delivery (e.g., synchronous video lectures vs. asynchronous self-paced modules),

- interactions (e.g., synchronous video discussions vs. asynchronous discussion forums), and

- activities and assessments (e.g., synchronous timed tests or oral tests vs. take-home open book test).

Challenges and affordances of synchronous aspects of virtual courses table (PDF)

Challenges and affordances of asynchronous aspects of virtual courses table (PDF)

Going deeper

For those wanting to take a deeper dive into the literature on synchronous vs. asynchronous virtual delivery before making design decisions, here is a literature review that provides more detail in this area. It focuses on factors for successful online courses, dimensions for comparing synchronous and asynchronous instruction, along with the research on affordances and limitations of both delivery methods:

If you’d like to explore more on how students develop online learning skills, see the following article:

Resources for students to help them learn how to learn in virtual learning contexts:

- “Study Tips for Online Classes Success” (article)

- Getting Ready to Learn Online (self-paced online module)

Strategies in action: Making the most of asynchronous delivery

Moving the laboratory into a virtual classroom

In this video, Dr. Cynthia Pruss, Queen’s University, outlines her experiences and lessons learned in moving a core undergraduate laboratory to the online space. She explains the important features of the course as it originally was run and how she ensured the online experience remained as equivalent as possible. She also reflects on how the process went and how students reported they engaged and enjoyed the course. This course is a higher resource and tool-intensive example.

Highlights include

- how a high degree of student support (office hours, questions and answer sessions) was organized and maintained,

- how early course surveys allowed for minor improvements as the course was running,

- how “live” science was translated into remote learning,

- how authentic online peer review was incorporated into the course,

- testimonials from students, and

- recognition that this is a high resource, tool-intensive experience where many collaborators worked together.

Teaching intro archeology via storytelling and videos

In this example, Dr. Barbara Reeves, Queen’s University, discusses how she converted her face-to-face course in introductory archaeological methods and techniques to an asynchronous online course. Using the proverb, “necessity is the mother of invention” she invented her own way to get over resource and time constraints. This is a limited resource and tool-conservative example.

Highlights include:

- creating “content storybooks” to support learning which included photos of graduate students and faculty ‘in action in the field’ so that students could imagine where they might be in a few years;

- releasing storybooks on a timed schedule to allow learners to focus deeply on a topic before moving on and to encourage active engagement with the course;

- how short, weekly assignments, weekly emails, and office hours increased engagement;

- videos created of the professor in the field (sometimes literally!) explaining course content and context;

- testimonials from students;

- how something as simple as a “punny” shirt or presence of a pet on course props can bring a lot of humor and enjoyment to students; and

- how she might re-adapt the material to bring it back to the physical classroom

Strategies in action: Making the most of synchronous delivery

When designing a new virtual course or redesigning a completely asynchronous course to include synchronous components, it can be difficult to visualize how this might be done for the most effective use of your and your learners’ time.

Common approaches are to have weekly or biweekly synchronous sessions for the whole class to conduct learning and collaborative work together. Tasks and activities may change week-to-week, but the expectation is that unless it is an optional Q&A/exam-prep session, participation is mandatory.

However, there could be value for learners to meet synchronously with the whole, or part of, the class just once or twice at a critical point in the semester. Meeting to present a summative assignment or debrief to discuss complex ideas at key points in the semester might help reduce cognitive load, reinforce key concepts, and allow learners to share their learning with the class, while keeping the overall course structure flexible and potential access and accessibility issues low.

Students mastering content through synchronous presentations

In a fourth year undergraduate neuroscience course, Dr. Susan Boehnke organizes her students (under 80 students) into groups of three. Students are tasked to complete an in-depth critical analysis of a scientific paper and prepare a 15-minute synchronous group PowerPoint presentation. The presentation is done over video-conference software and is followed by a 20-minute Q&A session where each student in the group is required to individually answer several questions from the instructor to demonstrate their knowledge and mastery of the content of the presentation and related concepts from the core course materials. This is good practice for a future thesis defence, or other such oral examinations.

Highlights of this approach:

- Flexibility: students are randomly assigned partners based on how they rank which weeks they would prefer to present; this forces them to learn to work with others who are not always their choice.

- High quality products: being in a group for the presentation allows students to produce a more complex product compared to if they worked alone. 2 to 3 students is ideal for this assignment.

- Targeted use of synchronous time: students only meet synchronously once during the semester; the presentation dates are known at the beginning of the semester and once students are in their groups and they have ranked their preferred presentation dates, the instructor organizes a specific time on that date to present.

- Balanced grade distribution, fairness, and reduced anxiety: most of the student’s grade is in the group mark; however, they must also be successful in individually answering questions in the live session. This can help high-performing students distinguish themselves from individuals who may have been carried by the group – a common source of anxiety and frustration from students.

- Real time connection: The students get to experience an almost one-on-one teaching and learning experience with the instructor, which is not very common in this type of learner’s context. The students get instant feedback on their presentation and can learn how rigorous scientific questioning works (and prepares them for graduate school, if that is their chosen path).

Students generally love the assignment as it is academically challenging and allows them to delve deeply into the discipline in small groups, but also allows them to control a part of their own grade.

What instructors have to say:

“These presentations are the highlight of my teaching in this online course – I get to meet each of my students one-on-one and have a deep conversation with them about a neuroscience topic. Students can demonstrate their oral presentation skills, and the TA and I can model appropriate scientific discussion and debate. The oral examination component often provides us with great insight into the student’s true knowledge and ability. Many students have reported that this is one of the most useful assignments of their undergraduate careers in terms of building real-world skills and increasing their confidence.”

(Dr. Susan Boehnke, online instructor)

What instructors have to say:

“We have also found it possible to implement student accommodations for live presentations. For example, students with anxiety have provided pre-taped narrations for their slides, or they choose to have their video off during the presentation. One student even provided answers to their oral examination questions in real-time by typing their answers in the zoom chat function. In rare cases we simply allow some accommodated individuals to present alone if it is their preference, though typically their partners have been supportive and empathetic.”

(Dr. Susan Boehnke, online instructor)

What learners have to say:

“Also, just wanted to thank for teaching this great course! Even with COVID and moving online, I felt like you and the TAs were all on top of things and cared about the success of the students. So thank you! Also, never get rid of the critical analysis assignment!! It was one of the most interesting assignments I’ve had to do, because I felt like it was really applicable to projects we would have to do in our life after graduation.”

(Julie, online learner)

Credit: Dr. Susan Boehnke, Centre for Neuroscience Studies, Queen’s Univerisity

Going deeper

If you are interested in exploring different activities for engagement and connection and how they could be implemented synchronously or asynchronously, the following resource from the Ontario College of Art and Design provides a quick overview of almost 40 activities with synchronous and asynchronous options:

Reflect and apply: Are you making the most of the delivery formats?

Reflect on your prior experiences teaching (and/or learning) in virtual contexts to identify pain points (opportunities for growth) in your course so you can more easily identify strategies that will help improve your and your learners’ experiences.

How to complete this activity and save your work:

Type your response to the question in the box below. Your answers will be saved as you move forward to the next question (note: your answers will not be saved if you navigate away from this page). Your responses are private and cannot be seen by anyone else.

When you complete the below activity and wish to download your responses or if you prefer to work in a Word document offline, please follow the steps below:

- Navigate through all tabs or jump ahead by selecting the “Export” tab in the left-hand navigation.

- Hit the “Export document” button.

- Hit the “Export” button in the top right navigation.

To delete your answers simply refresh the page or move to the next page in this course.

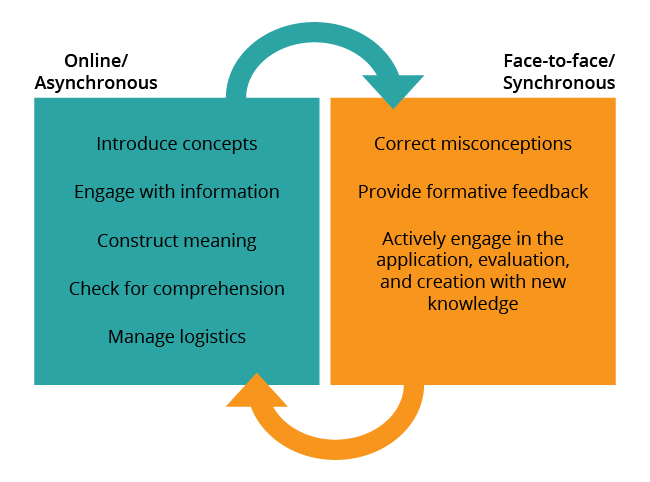

In conclusion, virtual courses have many affordances and challenges, but there remains lots of room to innovate, be creative, and be yourself with your students. If you are stuck in deciding how you might best use this method of teaching, viewing your course as a learning space that can be a combination of both synchronous and asynchronous could be helpful.

Consider the various course elements that are shown in the figure

Credit: Lauren Anstey, Centre for Teaching and Learning, Queen’s University

Even if your course cannot have synchronous elements, think about how you can make the higher-order thinking elements of your course ‘more human’ and more caring. The next sections of the module will explore these ideas in more detail.

References and credits

The sections “Virtual Learning Context,” “Characteristics of Your Virtual Learners,” and “Challenges and Affordances of Virtual Learning” are derived from original Fostering Engagement: Facilitating Online Courses in Higher Education, Unit 1. a by K.E. Wilson and D. Opperwall.

The original work is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, except where otherwise noted. This derivative work, “Virtual Learning Context,” “Characteristics of Your Virtual Learners”, and “Challenges and Affordances of Virtual Learning” has been adapted from the original through modification of text, images, and headings and retains the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.