Module 2: Designing for inclusivity

2.6 The road to decolonizing and Indigenizing a virtual course

Key principles: Looking within to take responsibility, looking forward to take action

Note

Readers should note that this section of this module was authored by a second-generation, female, able-bodied settler Canadian of central European descent and of middle-class upbringing, Jenny Stodola. I (Jenny) have summarized the discourse, principles, and strategies here as a snapshot representing my own journey towards decolonization and reconciliation undertaken as an intentional professional and personal development effort over the last three years. This work comes from my perspective as a white Settler instructional designer working in the post-secondary education (PSE) context and as a human being growing up, living, and working on the traditional territories of the Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee (Kingston and Napanee area) and unceded territories of the Algonquin (Ottawa area). I hope the lens I bring to the table can help others begin or continue their own reconciliation work. This does not represent a static piece of material, but as a springboard to further learning and understanding. It also attempts to privilege Indigenous perspectives, but I must disclose that in the process of writing this, I already am well aware that some important work by Indigenous scholars in the land we call Canada have not been included due to space and cognitive limitations. If this work speaks to you, consider searching for resources and scholars that tackle Indigenizing the academia, particularly in the Canadian context.

I am grateful for the opportunity to listen to and learn from Indigenous colleagues and Elders, learn from settler allies, and pass my growing and evolving understandings to those I collaborate with. I am grateful for the contributions of PSE colleagues to this work, but in particular for the guidance and support of Mitchell Huguenin and Blair Niblett for guiding the writing of this section.

It is well-recognized that colonization has had far-reaching effects on Indigenous Peoples in Canada, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis, from destruction of entire peoples, removal and displacement from traditional lands and legislation to resolve the “Indian Problem”’ (principally through the Indian Act, which further restricted freedoms of movement and removal of self-sufficiency). These colonizing acts have led to well-documented gaps in Indigenous health and wellness, related to the disconnection between Indigenous Peoples and their lands, governance, languages, and cultures, which includes their ways of knowing, teaching, learning, and being.

In the following video, Indigenous speaker and educator Eddy Robinson shares his story and explains why it is important that non-indigenous people of Canada listen to these stories and histories and not jump to solutions or try to help without understanding what has happened or without listening.

Transcript for What non-indigenous Canadians need to know is available on YouTube.

Credit: TVO Indigenous, 2019

As educators, we have a responsibility to walk a path of reconciliation and take action to do work to unravel detrimental and harmful colonial practices that have historically impacted the health, wellness, and vitality of Indigenous Peoples in Canada and continue to this day. This work is not just comprised of grand gestures, but much of the important work that needs to be done is through smaller and continuous acts of reconciliation. The ‘education’ of Indigenous children through Residential Schools and Indian Day Schools from the 1880s to 1996, through which “cultural genocide” (The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015, p. 1) was enacted, is of particular importance for the PSE sector in Canada to recognize, no matter the discipline.

. . . Reconciliation is about establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples in this country. In order for that to happen, there has to be awareness of the past, an acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behaviour.

(The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015, p. 6.)

For those of us who are settler Canadians, whether our ancestors arrived in Canada generations ago or are newcomers to Canada, we have the responsibility to ensure that we take steps to educate the next generation about our shared history and recognize the vibrancy and contributions of its original Peoples.

A quick word on the meaning of the term “settler”

As discussed in Beyond the Lecture: Innovations in Teaching Canadian History, a lot of people in Canada take offence to being called “settlers” even though the term is not derogatory.

Consider this excerpt from Beyond the Lecture:

Being a settler means that you are non-Indigenous and that you or your ancestors came and settled in a land that had been inhabited by Indigenous people (think: Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, etc.). However, it is important to recognize that while the term is not derogatory, it can often be very difficult to hear. Many people, particularly when first learning about the subject of settler colonialism, have strong and negative reactions to it. Most of us like to think that we are good people, and being told that we’re complicit in a colonial project can be emotionally wrenching. So we would like to encourage those who are interested in learning about this subject to make space for their feelings, recognizing them without judgement, and, whenever possible, to extend the same consideration to others. This is not to suggest that racist behaviour is acceptable under any circumstances, but, rather, that each person is on their own journey.

(Eidinger & York-Bertram, 2019. Used under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license)

Going deeper

To learn more about the term “settler colonialism” and guidelines related to learning and teaching about this topic, we recommend the following chapter from the Beyond the Lecture ebook, Imagining a Better Future: An Introduction to Teaching and Learning About Settler Colonialism in Canada.

Reconciliation as a settler responsibility

Educators have been implored to address the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC): Calls to Action, particularly the call to “integrate Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods into classrooms” (Call to Action #62).

The TRC Calls to Action #62–65 are specifically directed towards the education sector, but it is very important to note that the remainder of the 94 Calls to Action fall under all areas of life, including: child welfare, health, language and culture, justice, museum and archives, professional development, media and journalism, sports, and business/corporate, among others. Often these Calls to Actions are framed toward governments; however we can easily translate them to the PSE context given the often-publicly-funded aspect of the PSE sector as well as the fact that our graduates may work for governments or directly in these sectors in the future. The reality is that these Calls to Action touch all of Canadian society. No matter the discipline, there is real work to be done to reorient our perspectives of the country we call Canada and its history and contemporary reality, and to work for equity and justice in our disciplinary spheres.

Reconciliation is primarily a “settler responsibility,” though it benefits everyone. Indigenization and decolonization, which will be explored later in this section, is a shared responsibility among Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike.

Education got us into this mess and education will get us out.

(Justice Murray Sinclair, Head of Truth and Reconciliation Commission)

Reflect and apply: Stop and reflect on the TRC Calls to Action

Take a few minutes to read the Education for reconciliation sections in the TRC Calls to Action [PDF](62–65). If you have time, we strongly encourage you to also read or scan the 94 Calls to Action from the TRC, as you may find many of these overlap with your own work in PSE and with the learners you are teaching.

How to complete this activity and save your work:

Consider the questions and write out your initial ideas in the box below. Your answers will be saved as you move forward to the next question (note: your answers will not be saved if you navigate away from this page). Your responses are private and cannot be seen by anyone else.

When you complete the below activity and wish to download your responses or if you prefer to work in a Word document offline, please follow the steps below:

- Navigate through all tabs or jump ahead by selecting the “Export” tab in the left-hand navigation.

- Hit the “Export document” button.

- Hit the “Export” button in the top right navigation.

To delete your answers simply refresh the page or move to the next page in this course.

Going deeper

Indigenous history on Turtle Island

If you are unfamiliar with the colonial history of Canada, the first step is to do the emotional labour and take the time to do the research to educate yourself on these topics. There are a plethora of resources available out there, and many can be found online or at your local or institutional library.

The following keywords and links related to the history (particularly the post-contact history) of Indigenous Peoples on Turtle Island (the place we now call Canada) can help you in your research:

- First Nations / Inuit / Métis – Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada

- Treaties / Métis Scrip system

- Indian Act

- Residential schools / Indian day schools + intergenerational trauma

- Indian hospitals

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission Reports

- National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation – About NCTR

- Qikiqtani Truth Commission – Key Findings

- Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG)

- Implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada (UNDRIP)

A short readable article explaining the term “reconciliation” in the Canadian context:

Five national Indigenous leadership groups in Canada (not inclusively representing all Indigenous Peoples in Canada):

- Assembly of First Nations (AFN)

- Congress of Aboriginal Peoples (CAP)

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK)

- Métis National Council (MNC)

- Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC)

Note: If searching through video sites such as YouTube, we suggest that you privilege watching videos produced by Indigenous filmmakers, producers, or organizations, or first-person accounts/interviews so you can ensure to hear from Indigenous Peoples themselves rather than the standard Euro-Canadian-centric perspective. Finding such authors for content on websites/in scholarly articles may not be as easily discerned, so we recommend that unless seeking very specific governmental information, be sure to broaden your review beyond strictly government sources.

Some recommended multimedia resources include:

- Aboriginal Peoples Television Network

- Eagle Feather News

- CBC Indigenous (Indigenous reporters/producers such as Connie Walker, Duncan McCue, Ka’nhehsí:io Deer, etc.)

- Indigenous Cinema National Film Board

- imagineNative

- Many educational institutions now have an Indigenous resources or research guide offered through the central library which can act as a helpful launch point.

Key principles: Terminology

The term “Indigenous” is the most widely used, internationally-accepted, all-encompassing word used to refer to Indigenous peoples all over the world, and is the term used by the United Nations. Those living in Canada are legally referred to as “Aboriginal” in the Canadian Constitution, and these Peoples are represented by three distinct groups. These include the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit. However, prior to European contact, Indigenous Peoples in Canada were only comprised of First Nations and Inuit.

The terms “Indian” and “Aboriginal” still persist in our vocabulary due to the ongoing existence of government legislation such as the Indian Act, and, as mentioned, the inclusion of “Aboriginal” in the Canadian Constitution. However, “Indigenous” is the more widely used term in Canada today due to the colonial vestiges of the former terms. If one is referring to a broad range of groups, then “Indigenous Peoples” with a capital “I” and “P” and pluralized is often preferred as it acknowledges the diversity of Indigenous groups, and prevents “pan-Indigenous” thinking (i.e., the idea that all Indigenous Peoples are the same, where in reality, each group has a distinct culture and way of interacting with the world around them).

-

- Avoid “possessive” language such as “Indigenous Peoples of Canada” or “Canada’s Indigenous Peoples,” instead, use terminology such as “Indigenous Peoples in Canada.”

This terminology may seem confusing and overwhelming, but when in doubt, Indigenous Peoples generally prefer the most specific term available. This may be their Nation, their clan, or their community, among others. If in doubt, it is reasonable to ask for someone’s preference.

Going deeper

We can suggest a few resources for a deeper understanding of preferred terminology:

- Communicating Positively: A Guide on Terminology (Trent University)

- Indigenous Peoples terminology guidelines for usage (Indigenous Corporate Training Inc.)

- Briefing Note on Terminology (University of Manitoba)

- Terminology Guide (Queen’s University)

- Indigenous Terminology Guide (PDF, University of Waterloo)

- Use These Culturally Offensive Phrases, Questions at Your Own Risk (Indigenous Corporate Training, Inc.)

Key principle: Acknowledging our starting point

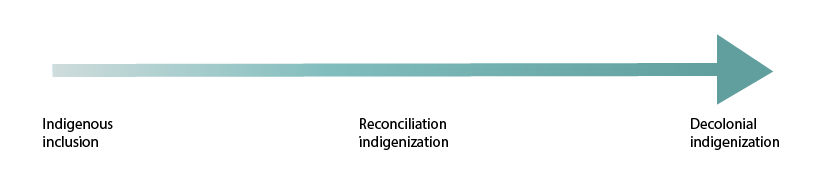

Generally speaking, decolonizing work in the Canadian academy is actually a misnomer and has been argued to actually represent a spectrum of three different uses for the term indigenization whose “meanings are not always compatible with one another, even if this incompatibility is obscured by an overlapping usage of the same terminology” (Gaudry & Lorenz, 2018).

Consider these important distinctions on the Indigenization spectrum:

Indigenous inclusion: “[A] policy that aims to increase the number of Indigenous students, faculty, and staff in the Canadian academy. Consequently, it does so largely by supporting the adaption of Indigenous people to the current (often alienating) culture of the Canadian academy.”

Reconciliation indigenization: “[A] vision that locates indigenization on common ground between Indigenous and Canadian ideals, creating a new, broader consensus on debates such as what counts as knowledge, how should Indigenous knowledges and European-derived knowledges be reconciled, and what types of relationships academic institutions should have with Indigenous communities.”

Decolonial indigenization: “[E]nvisions the wholesale overhaul of the academy to fundamentally reorient knowledge production based on balancing power relations between Indigenous peoples and Canadians, transforming the academy into something dynamic and new.”

Source: Gaudry & Lorenz, 2018

There are tensions in the work of Indigenization and decolonization as PSE struggles with how to ethically engage Indigenous communities and Indigenous knowledge systems. Although there have been Indigenous and settler scholars and educational support professionals trailblazing in these areas for many decades, we are still in the infancy of this work and often well-meaning policies are produced in a vacuum which can result in tokenism or in ultimately unsupportive situations. However, since the TRC Final Report release in 2015, momentum in PSE is growing and the beginnings of successful models are emerging. It is important that non-indigenous people take thoughtful steps towards Indigenous truth, inclusion, and reconciliation, as this is vital to Indigenization and lays the foundation for the development of robust systems, structures, and education spaces that can transform our education systems into something meaningful, vibrant, and new.

The following video highlights some Indigenous educators’ explanations of what they see as true reconciliation.

Transcript for What is reconciliation? Indigenous educators have their say is available on YouTube.

Credit: TVO Indigenous, 2019

We recognize it can feel incredibly intimidating and challenging to know where to start with this work, and to know how to actually start. The remainder of this section will explore some starting strategies to begin to incorporate reconciliation Indigenization principles into your work, not only to ensure any Indigenous learners in your courses feel seen and heard in your classes, but also so that we can ‘walk the walk and talk the talk’ of our responsibilities to reconciliation.

Quick tips and tricks: Understanding your motivations and the process

The Centre for Teaching and Learning at Queen’s University rightly points out that people often disagree about what the end goal of decolonization and Indigenization is or should be. Their suggestion to instructors is that rather than focusing on the end goal, you consider two elements:

- It’s important to think about the reasons you’re decolonizing: who are you doing it for and why are you doing it? This helps avoid issues of tokenism and recolonization.

- Remember that decolonization is a process, not a product. Instead of wondering where the finish line is, take a step along the journey and see where it leads you.

Credit: What is Decolonization? What is Indigenization? Centre for Teaching and Learning, Queen’s University,

Going deeper

Gaudry and Lorenz’s 2018 article provides for more in-depth explorations of Indigenization in the Academy. They also offer some additional readings for your further learning.

Tuck (2012) is a commonly referenced article that helps us understand that decolonization goes beyond thinking differently and that meaningful actions are required.

Strategies in action: Acknowledging our positionality and the approach to this work

Reflect and apply: Inspect the Indigenization levels

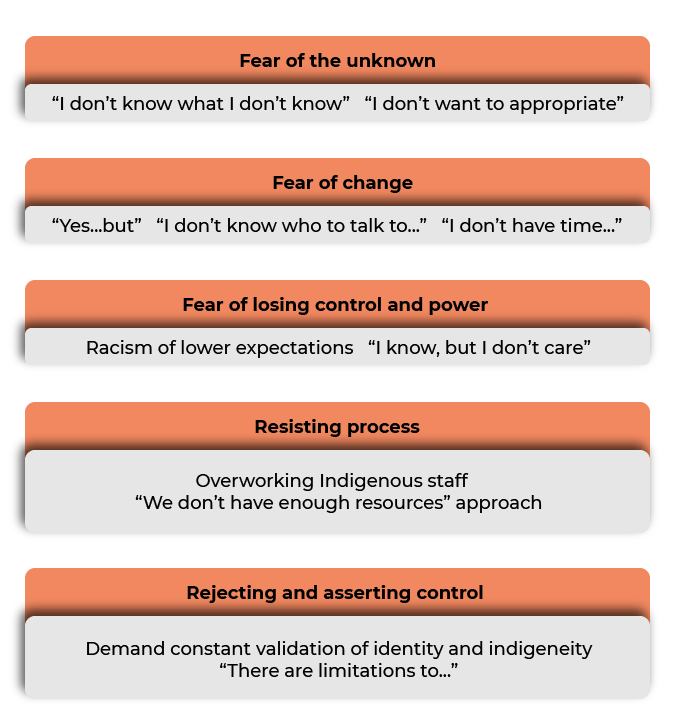

When doing decolonizing and Indigenizing work, it is important to continually reflect and situate yourself in your particular context. “We are all treaty people” is intended to emphasize that all people living in Canada have treaty rights and responsibilities. As educators our responsibilities include undertaking the work of Indigenization bravely, despite personal fears of concerns.

Using the levels of Indigenization offered by the authors of Pulling Together: A Guide for Teachers and Instructors, reflect on the questions posed and respond, either from your own perspective and how you feel yourself, or, from the perspective of how others are reacting to your work. Take a moment to sit with each set of questions but respond only to questions that resonate with you.

How to complete this activity and save your work:

Type your response to the question in the box below. Your answers will be saved as you move forward to the next question (note: your answers will not be saved if you navigate away from this page). Your responses are private and cannot be seen by anyone else.

When you complete the below activity and wish to download your responses or if you prefer to work in a Word document offline, please follow the steps below:

- Navigate through all tabs or jump ahead by selecting the “Export” tab in the left-hand navigation.

- Hit the “Export document” button.

- Hit the “Export” button in the top right navigation.

To delete your answers simply refresh the page or move to the next page in this course.

Wise practices in Indigenization

It is important to be honest on where you are along the reconciliation and Indigenizing journey.

How did you position yourself in the Indigenization levels above?

It is ok to have concerns and fears, even intense ones, but they must be confronted in order to move forward, for yourself and your learners. This leads us to three wise practices: knowing yourself, collaboration, and learning from mistakes.

In the following video, Ryerson professor Pamela Palmater shares her experience and approach to having honest, difficult, and often emotional conversations about reconciliation and Canada’s history with learners.

Transcript for Why do indigenous topics cause such emotional discomfort? is available on YouTube.

Credit: TVO Indigenous, 2019

Knowing yourself

Colonial systems persist in modern-day society, harming, ignoring, or disadvantaging Indigenous Peoples, often to the benefit (privilege) of non-Indigenous groups. Therefore, before the Indigenization process can begin, it is essential that instructors reflect critically on their own positionality. Unawareness of personal privileges and/or biases can hinder the ways in which they understand Indigenous approaches to teaching and learning – this is thus a critical first step (Huguenin, n.d.).

- Working through unlearning and relearning the collective histories of Canada is an emotional journey.

- Non-Indigenous instructors often feel anger, guilt, and shame for not having known about the atrocities levelled against a population in this country; confront these emotions and work through them.

- Instructors exploring ways to include Indigenous content have to reflect on and identify their own perceptions of Indigenous identity, along with their personal biases.

- Ask yourself the following questions:

- Whose truths are valued and represented in your course(s), discipline, institution?

- What counts as knowledge, and why is this?

- Jane Lew suggests to “[m]ake space, take space” (personal communication, 2017 in Pulling Together: A Guide for Teachers and Instructors). Give yourself time to explore and appreciate Indigenous worldviews and take the time to understand and disrupt beliefs and misconceptions.

Collaboration

Nothing about us, without us.

(Herbert, 2017)

This, or similar phraseology, has been used by many marginalized/oppressed peoples, especially in the disability activism community, but has most recently been used by a number of Indigenous, people of colour, and Black folks (Herbert, 2017).

It’s about building relationships

It is essential that the work of Indigenizing and decolonizing virtual education be done in partnership with Indigenous Peoples. Establishing relationships however, takes considerable time and effort, as many Indigenous People have experienced negative interactions with non-Indigenous institutions (e.g., the government, the education system, the healthcare system) in the past. Instructors will need to work hard to build relationships of trust that overcome the damage caused by colonization (Huguenin, n.d.).

Seek guidance and resources offered by your institutions

Most institutions have staff that can support this process—for example, Indigenous support services staff, or a colleague who has established strong, positive relationships with Indigenous partners. Also seek allies, persons such as yourself, who are on the reconciliation journey so you can learn from each other and build stronger support systems for Indigenization at your institution.

During an initial meeting, be it with an Indigenous staff member, Indigenous support services unit, Elder, Indigenous academic or community member, you should be clear about your goals, ask questions, be prepared to make mistakes and, as necessary, apologize for those mistakes. This is a lifelong process that can be challenging, but through patience and practice, relationships will grow.

- Professional humility is being aware that we cannot know everything.

- Indigenous knowledge is highly contextual and strongly grounded to the land; local knowledge is all around us – explore institutional and relational supports (e.g., communities themselves or community centres or organizations).

- Ask your questions with a kind heart and an open mind.

- Ask your questions with the understanding that some of the work required to answer them is yours.

Your (un)learning is your responsibility

It is important that we each take responsibility for our own (un)learning. When seeking guidance from Indigenous colleagues, staff, or community members, it is important that we not shift that burden onto those individuals. Understand that quite practically speaking there are fewer Indigenous than non-Indigenous persons in the postsecondary sector to begin with because of long-standing colonization policies and practices which creates a system that is difficult for Indigenous Peoples to enter. These persons who are in PSE are often overworked at their institutions, and while often willing and wanting to help, you need to be careful of how much you ask for, not only in workload but in terms of emotional labour. This is why your own learning journey is extremely important.

Going deeper

The following article provides a commentary on taking responsibility for our own (un)learning from Mel Lefebvre, a Red River Métis/Irish writer and visual artist living on Kanien’kehá:ka Territory: “It’s not My Job to Teach You About Indigenous People”

Before reaching out to Indigenous scholars, community members, or Elders, consider the ideas of relationality, reciprocity, and potential protocols that need to be attended to before you take the first step. Jesse Popp, an Indigenous scholar, offers 10 considerations to help those intending to reach out for information or collaboration.

Learning from mistakes

As alluded to previously, the fear of making a mistake inhibits necessary work. Learning from mistakes is a common aspect of Indigenous pedagogy; it involves experiential learning and self-development.

After the process of acknowledging and fixing a mistake, it’s then time to let go, move forward, and continue to work together.

You may feel uncomfortable when you make mistakes but try to also be grateful for the opportunity to learn and ask questions.

Going deeper

In building your Indigenized practice, the authors of Pulling Together: A Guide for Curriculum Developers provide additional insights from Indigenous and non-Indigenous educators and their experiences with mistakes. The following link will take you to this section of the book:

Key principle: Indigenous epistemologies and pedagogies

Indigenous epistemologies (how knowledge can be known) and pedagogies (how knowledge can be taught) have quite a different starting point from common Western approaches to knowing and teaching. However, if we gain an understanding of Indigenous approaches, we can thoughtfully interweave them into our curricula. While there is much diversity among Indigenous Peoples, and therefore among Indigenous way of knowing, teaching, or learning, many Indigenous education scholars have argued there are also some notable commonalities among Indigenous societies worldwide.

The following content has been adapted from the open educational resource, Pulling Together: A Guide for Curriculum Developers, Section 2: Meaningful Integration of Indigenous Epistemologies and Pedagogies to give you a brief overview of Indigenous epistemologies and pedagogies.

Indigenous epistemologies

Consider these Indigenous epistemologies

Relationality: Relationality is the concept that we are all related to each other, to the natural environment, and to the spiritual world, and these relationships bring about interdependencies. Instructors and course designers can apply the concept of relationality by creating learning opportunities that emphasize learning in relationships with fellow students, teachers, families, members of the community, and the local lands.

Sacred and Secular: According to Hoffman (2013), “Aboriginal ontologies and epistemologies are rooted in worldviews that are inclusive of both the sacred and the secular. [In Indigenous ontologies] the world exists in one reality composed of an inseparable weave of secular and sacred dimensions” (p. 190). In Western educational approaches, spirituality is often seen as taboo in the classroom. In an Indigenous approach, spiritual dimensions cannot be separated from secular dimensions, and spirituality is a necessary component of learning. This does not mean that students need to embrace a specific “religious” approach or practice, but rather, educators interested in incorporating Indigenous epistemologies into their course should consider spiritual development as a component of learning.

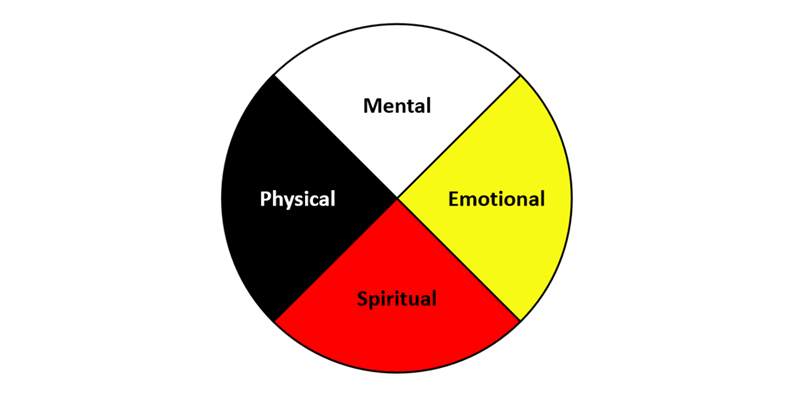

[W]holism: The principle of holism/wholism is linked to that of relationality, as Indigenous thought focuses on the whole picture because everything within the picture is related and cannot be separated. Cindy Blackstock (2007), the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, identifies four interconnected dimensions of knowledge that are common in Indigenous epistemologies: “emotional, spiritual, cognitive, and physical,” which are “informed by ancestral knowledge which is to be passed to future generations” (p. 4). In Indigenous epistemologies, these four elements are inseparable, and human development and well-being involves attending to and valuing all of these realms. Oftentimes, you may see this represented by the image of the medicine wheel/sacred hoop.

Credit: Yunyi Chen, Centre for Teaching & Learning, Queen’s University | Holistic Framework

Indigenous philosophies are underlain by a worldview of interrelationships among the spiritual, the natural and the self, forming the foundation or beginnings of Indigenous ways of knowing and being.

(Willie Ermine, 1995)

Indigenous pedagogies

A basic assumption of Indigenous education scholars is that there are modes of Indigenous pedagogy that stem from pre-contact Indigenous educational approaches and are still ingrained in Indigenous contemporary culture. The exclusion or devaluation of Indigenous pedagogies can create a barrier to academic success for Indigenous students, limit a genuine understanding of Indigenous culture and history for all students, and prevent people from learning how to exercise highly valuable and useful modes of thought which could potentially address many problems in the modern world. Some key commonalities among Indigenous pedagogical approaches are outlined below.

Consider these Indigenous pedagogies

Personal and holistic: As a result of the epistemological principle of (w)holism, Indigenous pedagogies focus on the development of a human being as a whole person. Academic or cognitive knowledge is valued, but self-awareness, emotional growth, social growth, and spiritual development are also valued. It is useful for instructors and course designers to keep this in mind when creating learning experiences that interweave both Indigenous and Western ways of knowing.

For example, Indigenous approaches can be brought to life by providing opportunities for students to reflect on the four dimensions of knowledge (emotional, spiritual, cognitive, and physical) when they engage in learning activities. This may also include allowing students opportunities to challenge dominant ideologies that neglect emotional and spiritual knowledge domains.

Experiential: Indigenous pedagogies are experiential because they emphasize learning by doing. In traditional pre-contact societies, young people learned how to participate as adult members of their community by practicing the tasks and skills they would need to perform as adults. In a contemporary setting, an emphasis on experiential learning means a preference for learning through observation, action, reflection, and further action. For instructors and course designers, this also means acknowledging that personal experience is a highly valuable type of knowledge and method of learning, and creating opportunities within courses for students to share and learn from direct experience.

Place-based learning: Indigenous pedagogies connect learning to a specific place, and thus knowledge is situated in relationship to a location, experience, and group of people. For curriculum developers, this means creating opportunities to learn about the local place and to learn in connection to the local place.

Intergenerational: In Indigenous communities, the most respected educators have always been Elders. In pre-contact societies, Elders had clear roles to play in passing on wisdom and knowledge to youth, and that relationship is still honoured and practiced today. Some Elders are the knowledge holders of 60 different Indigenous languages in Canada, and language is a key component of Indigenous culture that should be integrated in teaching practices if we are to move toward Indigenization of curriculum. Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students can learn a lot from Elders, and instructors and course designers can seek opportunities to engage with Elders as experts in Indigenous pedagogies.

Note

The appropriate use of Indigenous pedagogies

Misappropriation (using the intellectual property, traditional knowledge, or cultural expressions, from a culture that is not one’s own without permission) challenges Indigenous Peoples’ rights of expression, protection and transmission of cultural knowledge. As such, there are important protocols that instructors must follow to ensure the appropriate and respectful use of Indigenous pedagogies and resources:

In the mainstream academic system, copyright is used to ensure permission for written resources. In Indigenous cultures, oral permission is required to use cultural materials or practices such as legends, stories, songs, designs, crests, photographs, audiovisual materials, and dances.

(Antoine et al., 2020)

Permission to use such materials or practices may be considered in the context of one’s intent and relationship with the owners.

Instructors must therefore build connections with Indigenous communities so that they can incorporate Indigenous culture in ways that are not harmful or exploitative.

This may be harder work than simply adding an Indigenous text, speaker, or activity into a course, but it is the responsibility of all educators to engage in this work.

(Antoine et al., 2020)

Credit: Mitchell Huegenin, Trent University (Integrating Indigenous Pedagogy in Remote Courses)

Key principle: Connecting Indigenous ways of knowing, teaching, and learning to humanized learning

If you have worked through Module 1 you may have already started to make the connection between Indigenous ways of knowing, teaching, and learning with key principles of humanized learning, including Fink’s taxonomy of the six dimensions of significant learning and the three types of connection for significant learning (learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content).

When we thoughtfully and appropriately integrate Indigenous worldviews into our courses, we can create a more rich, deep, and inclusive learning experience for all students. At the same time, it provides an opportunity to pause, take a step back, and critically evaluate learning outcomes, content, and assessment design from a completely different perspective. This type of critical evaluation is by no means easy and takes a lot of personal development, learning, and support to achieve, however when framed in the context of humanizing the course experience, this can seem less daunting. Several approaches to this type of work are offered for your consideration the rest of this section, holistic frameworks for learning, assessments that align with Indigenous ways of teaching and learning, and connecting to the land in virtual spaces.

Strategies in action: Using holistic frameworks for learning

Creating holistic learning outcomes based on Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning

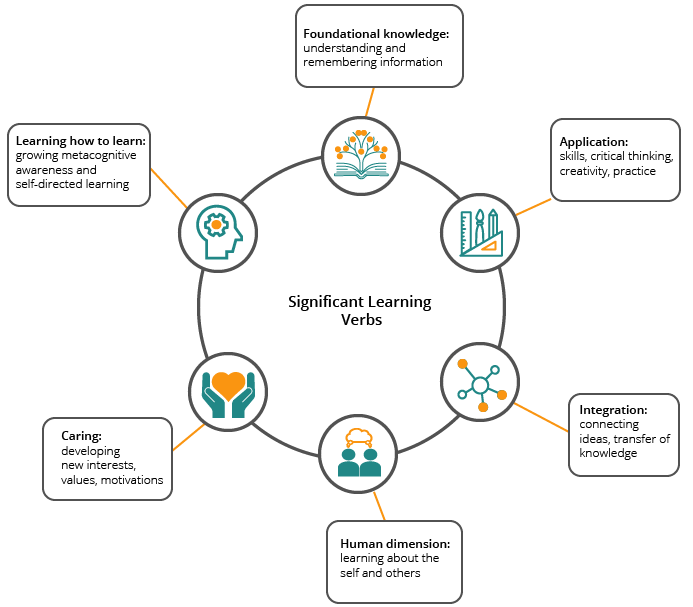

Recall that in Module 1.3 Setting the Stage for Significant and Courageous Learning, you were introduced to Fink’s taxonomy of significant learning which included six dimensions that focus on a change or transformation in the learner. The six dimensions include

- foundational knowledge,

- application,

- integration,

- human dimension,

- caring, and

- learning to learn.

While these form a strong foundation in humanizing the learning experience, there are still gaps in how the relational, emotional, and spiritual aspects of learning privileged by Indigenous ways of learning and teaching are represented.

Visit the following interactive resource which presents a decolonized and holistic approach to developing learning outcomes in the online context using the Haudenosaunee Four Directions teaching as a framework on which to incorporate Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning. The interactive tool begins with some educational material to understand the holistic framework and then provides examples of how to address each element and opportunities to attempt your own learning outcomes using this framework.

Creating holistic learning outcomes and rubrics based on Bloom’s taxonomy

Many PSE educators may be more familiar with Bloom’s taxonomy of learning. Marcella LeFever provides insightful documentation of her journey towards Indigenizing her classroom practices as a non-Indigenous educator. In her 2016 article, she documents how she found opportunities to incorporate elements of spirituality, honouring, attention to relationships, a sense of belonging, and self-knowledge of purpose to the typical PSE classroom by adapting the traditional three hierarchical levels of Bloom’s to the four domains of the Medicine Wheel used by many Indigenous cultures in Canada. She provides a detailed four-domain framework that balances physical, spiritual, emotional, and intellectual domains of learning. In addition, recognizing that non-Indigenous educators may find it a challenging area, she provides further guidance for documenting progression through the spiritual domain of the framework (LaFever, 2016). This resource could be helpful not only for creating holistic learning outcomes but also perhaps for consideration of a new holistic approach to (circular) rubric design and evaluation.

Going deeper

If you are not familiar with how to use Bloom’s taxonomy to write effective learning outcomes or require a refresher, we recommend the following unit from the ebook, High Quality Online Courses: How to Improve Course Design & Delivery for your Postsecondary Learners or you can also review section 1.6 Writing Effective Learning Outcomes (Event 2).

Strategies in action: Assessments aligned with Indigenous ways of teaching and learning

Indigenous assessment approaches integrate the epistemological and pedagogical approaches discussed earlier in this section. Some key considerations would be learning activities that are land-based, narrative, intergenerational, relational, experiential, and/or multimodal (e.g., rely on auditory, visual, physical, or tactile modes of learning). While assessments will not be exhaustively covered in this resource, as discussed in Pulling Together: A Guide for Curriculum Developers, adapting learning activities without changing other aspects of the curriculum is not a holistic approach to Indigenization, and in some cases can result in trivializing and misappropriating those activities. Interweaving Indigenous approaches should involve considering all of the following aspects of your course design:

- Goals: Does the course goal include holistic development of the learner? If applicable, does the course benefit Indigenous people or communities?

- Learning outcomes: Do the learning outcomes emphasize cognitive, emotional, physical, and spiritual development? Is there room for personalization, group and individual learning goals, and self-development?

- Assessment: Is the assessment holistic in nature? Are there opportunities for self-assessment that allow students to reflect on their own development?

- Relationships: Are there opportunities for learning in community, intergenerational learning, and learning in relationship to the land?

- Format: Does the course include learning beyond the classroom “walls”?

How to approach this type of work as a non-Indigenous instructor: A criminology case study

Many instructors are new to considering how they may reorient or reframe their course design to engage with decolonizing or Indigenizing efforts. It can be challenging to know where to start.

For your deeper (un)learning and appreciation, click to listen to a podcast featuring Dr. Stephanie Ehret, Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at Trent University. With her, we explore her (un)learning journey and process of incorporating Indigenous knowledge and worldviews and the beginnings of a decolonization approach into her undergraduate philosophy and criminology course as well as how she creates a safe community for learning about challenging and sensitive topics.

Discussions points include the following:

- An overview of her course and the process of why and how Dr. Ehret decided to incorporate Indigenous perspectives and local knowledge into the course structure and material (0:00 – 12:23);

- How to navigate the challenges and fears one might have when undertaking this type of process for the first time, and overcome them (12:24 – 16:05);

- Approaches in assignment design and facilitation approaches that aim to create a safe virtual learning environment for learners given the intrinsically challenging and sensitive nature of the material discussed throughout the course (16:06 – 20:22);

- Advice for others who are trying to undertake similar processes in their course design work (20:23 – 23:41).

Transcript (PDF)

Credit: Dr. Stephanie Ehret, Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology, Trent University

Going deeper

The following resources provide faculty perspectives, approaches, and strategies for Indigenization and decolonization of courses.

What I Learned in Class Today: Aboriginal Issues in the Classroom is a research project that explores difficult discussions of Indigenous issues that take place in classrooms at the University of British Columbia. In the following resource, faculty discuss their perspectives and strategies related to discussing Indigenous issues in the classroom.

Dr. Shauneen Pete provides a commentary for indigenizing and decolonizing academic programs.

The following resources provide more discipline-specific examples:

Strategies in action: Connecting to the land in virtual spaces

Virtual learning is often framed as “landless territory” and it can be difficult to conceptualize how one can bring the land, an important part of Indigenous pedagogy, into the virtual space. Indigenous pedagogies emphasize authenticity as a required condition for learning; however, virtual learning can often feel impersonal or detached from students’ personal and everyday lives, i.e., there is a gap between “internal” and “external” experiences (Huguenin, n.d.). The nuance of subtle energy generated from self-reflection and openly sharing with others provides a sense of community and interconnectedness that is not often present in most traditional classrooms and is especially difficult to duplicate in online settings (Huguenin, n.d.). A few simple approaches to bridge these challenges are suggested.

Learning about the land

Engage your learners in research about the land they are situated on, should this be at their institution or a place that is significant to them. Understanding which Indigenous territories they are located on, the historical Treaties or other agreement(s) that were enacted as part of colonization, and learning about local languages and culture can help learners connect to their environment.

A starting point for learning about traditional territories include Native Land and Whose Land.

Self-directed interaction with the land

Moving beyond research to learn about the land on which they are situated, virtual learners can be engaged with the land through self-guided reflective exercises and subsequent debrief through a sharing circle. This can be designed as a personal reflection, or, depending on the course topic, (e.g., urban planning, environmental science, biology, geography, agriculture, veterinary science, construction, engineering, language studies, creative arts, business, etc.) such an activity can be adapted to reflect on or interact with elements that learners in all regions would likely be able to access and would at the same time address the intersection of discipline-specific contexts and Indigenous holistic approaches.

For a sample activity that illustrates this idea as a personal reflection, click the following link:

Creating course content on the land

As an instructor for the course, an easy way to take the learning outside of the virtual space, is to situate yourself in the environment (when possible). Recording yourself with a smartphone beside a man-made or natural feature in your community that is related to course content is an effective way to ground learners in the physical world, rather than discussing abstract concepts. Even recording fieldwork or yourself in your workplace can be a helpful, humanizing element to the course.

Remember, no matter how urban a location that we live in might be, we remain connected to the land in the places we live, work, and play, as well as through the water we drink, the food we eat, and the air we breathe.

If it is not possible to record course content outside your office, consider recording a simple welcome message or weekly announcements outside to strengthen your connection to learners and the physical environment.

It is important to acknowledge that through this approach, as a non-Indigenous person, you would not be engaging in the practice of land-based learning. This is an entirely different pedagogical approach (commonly termed Indigegogy) and not something that can be appropriated or even considered without extensive consultation with community and Indigenous scholars. This is merely a small suggestion to help humanize and connect your learners to the physical space of the world around them even though the course material is being delivered via electronic methods.

Going deeper

For further support of your learning, six Indigenization Guides provide a set of professional learning guides offered by BCcampus as open educational resources. These guides are the result of a collaboration between BCcampus and the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training. The project was led by a steering committee of Indigenous education leaders from BC universities, colleges, and institutes, the First Nations Education Steering Committee, the Indigenous Adult and Higher Learning Association, and Métis Nation BC. The content in these guides is authored by teams of Indigenous and ally writers from across BC as open educational resources to be used in BC and across Canada. These are highly recommended resources for your own learning, and subsequent use and adaptation to specific contexts. Indeed, we have already highlighted some of their content in this module.

Access the learning guides:

- Foundations

- Teachers and Instructors

- Front Line Staff, Advisors, and Student Services

- Leaders and Administrators

- Curriculum Developers

- Researchers

These open resources are also found in the eCampus Ontario catalogue where you will also be able to find additional courses on Indigenization, decolonization, and associated topics for further in-depth learning.

References and credits

Blackstock, C. (2007, January). The breath of life vs. the embodiment of life: Indigenous knowledge and Western research. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237555666_The_breath_of_life_versus_the_

embodiment_of_life_indigenous_knowledge_and_western_research

Ermine, W. (1995). Aboriginal epistemology. In M. Battiste & J. Barman (Eds.), First Nations education in Canada: The circle unfolds. (pp. 101–112). UBC Press.

Gaudry, A., & Lorenz, D. (2018). Indigenization as inclusion, reconciliation, and decolonization: Navigating the different visions for Indigenizing the Canadian academy. AlterNative : An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 14(3), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180118785382

Herbert, C. (2017). “Nothing about us without us”: Taking action on Indigenous health. Longwoods. https://www.longwoods.com/content/24947/insights/-nothing-about-us-without-us-taking-action-on-indigenous-health

Hoffman, R. (2013). Respecting Aboriginal knowledge in the academy. Alternative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 9(3), 189–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011300900301

Huguenin, M. (n.d.). Integrating Indigenous pedagogy in remote courses. Teaching and Learning, Trent University. https://www.trentu.ca/teaching/integrating-indigenous-pedagogy-remote-courses

The section “A Quick Word on the Meaning of the Term ‘Settler'” was derived from original by Eidinger, A. and York-Bertram, S. (2019). Imagining a better future: An Introduction to teaching and learning about settler colonialism in Canada. In A. Eidinger & K. McCracken (Eds.), Beyond the lecture: Innovations in teaching Canadian history, which is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. The derivative work, “A Quick Word on the Meaning of the Term ‘Settler'” has been adapted through modification of text, images, and headings and retains the CC BY-NC-SA International 4.0 license.

The sections “Indigenous Epistemologies,” “Indigenous Pedagogies,” and ”An important note on appropriate use of Indigenous Pedagogies” are derived from original by Antoine, A., Mason, R., Mason R., Palahicky S., & Rodrigez de la France, C. (2018). Indigenous epistemologies. In Pulling together: A guide for curriculum developers, which is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. The derivative work, ‘Indigenous Epistemologies,’ ‘Indigenous Pedagogies,’ and ‘An important note on appropriate use of Indigenous Pedagogies’ have been adapted through modification of text, images, and headings and retains the CC BY-NC-SA International 4.0 license.

The sections “Navigating the Levels of Indigenization,” “Knowing Yourself,” and “Indigenous Pedagogies” are derived from original by Allan, B., Perreault, A., Chenoweth, J., Biin, D., Hobenshield, S., Ormiston, T… & Wilson, J. (2018). Respectfully opening your heart and mind to Indigenization and holding space and humility for other ways of knowing and being. In Pulling together: A guide for teachers and instructors, which is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. The derivative work, “Navigating the Levels of Indigenization,” “Knowing Yourself,” and “Indigenous Pedagogies” have been adapted through modification of text, images, and headings and retains the CC BY-NC-SA International 4.0 license.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf