Module 2: Designing for inclusivity

2.4 Universal design for learning and equitable access to online content

Key principles: Inclusive learning – A well-planned dinner party

Inclusive education theorist Mara Sapon-Shevin (2007) compares inclusive learning environments to that of a well-planned dinner party. When we plan a dinner party, we want guests to be able to enjoy tasty and nutritious food, as well as a positive social experience. Likewise, in creating inclusive virtual learning spaces, we want to create the opportunity for as many learners as possible to participate in interesting and engaging learning, which leverages the social and human components of learning.

The success of both a dinner party and virtual course depends on careful planning from beginning to end to ensure that the needs of each guest/learner are met, and no one is excluded. Because we typically plan dinner parties for our closest friends and family, we are quick to anticipate and respond to the unique needs of individual guests.

Conversely, because we plan virtual learning experiences for a broadly imagined “general public,” it can be easy to overlook unique individual needs—especially for learners who experience a disability or a social frame or identity that is often excluded (either directly or systemically). Just as we would adapt for, or accommodate, our dinner party guests (e.g., provide an alternative meal for a lactose-intolerant guest, eliminate all nut products to welcome a guest with a serious allergy, or rearrange furniture to ensure access for a friend using a mobility aid), humanizing learning calls on us to design experiences in ways that facilitate access, engagement, and inclusion. Universal design for learning is a framework for designing inclusive learning experiences that help ensure everyone feels welcome and is able to participate.

Key principles: Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

As explored in section 1.5. Learner–Content Connection: Designing Valuable Learning Experiences, UDL provides a framework for creating courses that are accessible for all learners, regardless of their disability status. UDL provides a

[f]ramework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn … [and] offer[s] a set of concrete suggestions that can be applied to any discipline or domain to ensure that all learners can access and participate in meaningful, challenging learning opportunities.

(CAST, 2018)

There are three key principles to keep in mind for UDL:

Multiple means of representation

Provide multiple means of representation or present content and information in different ways. This is the “what” of learning.

This includes providing content that is accessible through different modalities, such as ensuring that text information can be accessed through screen reading software but the size of the text can also be adjusted, or that multimedia (audio and video) has accompanying captions and transcripts. This makes it perceptible.

Multiple means of representation also means clarifying vocabulary, symbols, taxonomies, equations, etc., describing content in different ways, and using summary graphics, activities, videos, or multiple examples for the same topic to increase clarity and comprehensibility across all learners.

Finally, proper design and presentation of the information can provide the necessary scaffolds to ensure that all learners have access to knowledge. This can be achieved by activating or providing background knowledge to help build connections to prior understandings and experiences as well as highlighting patterns, critical features, big ideas, and relationships and relating them to the learning goal. Meaning-making can also be enhanced through models, scaffolds, and feedback, while reinforcement can be achieved by applying information to new contexts.

Multiple means of representation create expert learners who are resourceful and knowledgeable.

Multiple means of action and expression

Provide multiple means of action and expression or allow learners to express what they know in different ways. This is the “how” of learning.

Ensuring that your material is accessible through assistive technologies (e.g., screen readers) is one way that your learners can have multiple means of action to access your content. However, don’t feel overwhelmed with this point; offering multiple modalities in your communication of concepts, as described in the multiple means of representation section is a strong way to support this arm of UDL. In addition, connecting with your institution’s accessibility office can offer you support in this area as well as your learners, who may require specific services (e.g., paying for software for learners’ computers or having course content converted to braille).

Providing a variety of activities and assessments in the course, with different ways of communicating knowledge (e.g., allowing learners to create either an essay, podcast, or video presentation) can also provide learners with the ability to find the best way to express their knowledge in a way that complements the learning goal. Building in multiple means of expression supports learners’ multiple means of action with your content and assessments.

Further, learner expression is facilitated by gradually releasing scaffolds to support independent learning. This could mean that at the beginning of a course you may provide a lot of examples or guidance for content learning and assessment completion, but through instructor feedback and their own experience, learners can become more independent as the course proceeds. To complement this, structuring a course with clear learning goals and scaffolding weekly learner goals and tasks, helps learners structure their learning in a virtual learning environment with limited supervision and high independence. The various design strategies you have already explored in this course such as understanding the affordances and challenges of virtual courses explored in Module 1, and the facilitation strategies you will explore further in Modules 3 and 4, will intrinsically assist in this area.

Multiple means of action and expression create expert learners who are strategic and goal-oriented.

Multiple means of engagement

Provide multiple means of engagement or offer options to stimulate interest and motivate learners. This is the ‘why’ of learning.

This principle focuses not so much on the modality of the content presentation, but on the forms of interaction. To recruit interest and spark excitement and curiosity for learning, you can ensure the learner-learner, learner-instructor, and learner-content interactions have relevance, values, and authenticity. One cannot assume that all learners will find the same activities or information equally relevant or valuable to their goals but providing options and different perspectives can enhance engagement and motivation.

When interactions and sources of information are contextualized to learners’ lives and provide a diverse set of perspectives that are culturally or socially relevant and responsive, learners will be motivated and engaged. Designing activities with clear purposes, that are related to real-life or relevant problems, and allow for active participation, exploration, and experimentation, allows learners to engage with content, the instructor, and peers in meaningful ways. Deepening personal connections to courses by inviting personal responses, evaluation, and self-reflection on content and activities also strongly grounds learners in their learning process and community, increasing their motivation to be engaged. Facilitating and fostering a collaborative and engaged learning community is further explored in Modules 3 and 4.

Multiple means of engagement creates expert learners who are purposeful and motivated.

Key principle: UDL for equitable design

It is emphasized that UDL is designed to improve learning for everyone, however we have a particular ethical and legal responsibility to ensure learners with disabilities have equitable access to our learning spaces. The Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) is a statute enacted in 2005 by the Legislative Assembly of Ontario to improve accessibility standards for Ontarians with physical and mental disabilities to all public establishments by 2025.

The purpose of the AODA is to develop, implement, and enforce accessibility standards or rules so that all Ontarians will benefit from accessible services, programs, spaces, and employment. The standards help organizations to prevent or remove barriers that limit the things people with disabilities can do, the places they can go, and the attitudes of service providers toward them.

(Thomson, 2018, emphasis added)

While Ontario was the first province to enact such ground-breaking legislation, interestingly while there are five standards that all organizations (including educational institutions) must follow (information and communications; employment; transportation; design of public spaces; customer service), as of mid-2021 there was no explicit education standard.

Recommended AODA education standards for digital learning and technology

The AODA Postsecondary Education Standards Development Committee propose a number of recommendations for decreasing barriers and ensuring publicly-funded postsecondary education is more accessible to people with disabilities. Many different areas are covered, but highlighted themes are reducing barriers to accessible online learning and addressing accommodations through a UDL approach.

Six key AODA recommendations for virtual learning in higher education:

- Accessible technology

- Accessibility plan

- Accessible procurement support

- Accessibility training/practice

- Accessible and inclusive pedagogy/andragogy

- Accessible content

Going deeper

To learn more about the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act or the lack of standards for educational institutions see the following pages from the AODA website:

You can access the full report of the AODA standards development committee recommendations at the following link; however, for the purposes of the design of a virtual course, the UDL approach provides us with a strong foundation, and we will remain focused in this area for the rest of the section:

Understanding the difference between accessibility and accommodation

It is likely that if we do not experience a visible or hidden disability, then we might think that the terms “accessibility” and “accommodation” are interchangeable terms, but this is incorrect.

Definitions

Accessibility “is what we should expect to be ready for us without asking or planning ahead. It can be provided by following an easy to implement set of standards and practices that make ‘adaptation’ unnecessary. We can benefit from accessibility without announcing or explaining our disabilities” (Pulrang, 2013, emphasis added).

Accommodation “is for adaptations that can’t be anticipated or standardized. They are different for each individual. Although we should expect there to be a general willingness to accommodate us wherever we go, we can’t expect actual, specific accommodations unless and until we ask for them. We do have to announce, and may have to explain our disabilities a bit in order to get accommodations” (Pulrang, 2013, emphasis added).

Accessibility is the baseline of equal service, and accommodation is the second step to take when accessibility alone isn’t enough.

(Andrew Pulrang, 2013, emphasis added)

UDL provides a strong framework for proactively ensuring that a majority of our content and design is accessible, and the need for reactive individual accommodations is reduced.

Quick tips and tricks: Fundamentals in virtual accessible learning

If you are designing a humanized experience, you likely have already been implementing UDL principles in your content and assessment structures, however, presented are some design fundamentals to keep in mind.

- Consider font choice for readability (e.g., sans serif, no italics or shadowing, consider the relative font size for your medium to ensure it is readable).

- Consider the contrast of various elements (e.g., text on background, text over image, green-red colour blindness).

- Describe nontext elements (e.g., charts, tables, images, logos, including text on images, etc.); this is called descriptive or alt text.

- Ensure to provide captions and a transcript for all audio and video clips.

- Ensure as many elements in your content are controllable by the learner (e.g., audio can be started and stopped, an animation can be replayed, there is a way to enlarge images or text).

Going deeper

Want to ensure the materials you create are accessible to all your learners?

The POUR principles are a great place to start:

- Perceivable: Present information in multiple ways

- Operable: Provide options for navigation

- Understandable: Create an intuitive experience

- Robust: Ensure compatibility

The pages above from the National Centre on Accessible Educational Materials: Designing for Accessibility with POUR provides many tutorials on how to make Word, Google, and PDF documents accessible, how to write descriptive text (alt text), how to use built-in accessibility checkers, locate or create captions for videos, and more.

The POUR principles define four qualities of an accessible experience and they are at the foundation of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), an international standard for making web content accessible.

If you are looking for a nontechnical solution for accessible content creation, the University of British Columbia has created an OER Accessibility Toolkit. OERs are Open Educational Resources, and this toolkit aims to provide core resources needed to create truly accessible educational resources—ones that are accessible for all students.

Finally, the University of Toronto – Ontario Institute for Studies in Education offers an education commons page specifically on Accessibility Tools and Resources which offers a variety of accessibility checkers, checklists, and testing functionalities that allow you to gauge if your content is accessible. There are also many resources specifically dedicated to creating an accessible website.

Strategies in action: Multiple means of representation

With multiple means of representation, we aim to make the information perceptible to learners by presenting the same content, concepts, or ideas in different ways, either through different delivery modalities, different examples/metaphors (also through various modalities), or through clarifying language. We ensure that learners have the background knowledge they need to build up their skills to scaffold into higher-order learning as the course progresses. We aim to support resourceful and supported knowledgeable learners.

Example of multiple means of representation from Module 1:

- Providing assignment descriptions in text form, providing an exemplar assignment, and posting an announcement clarifying assignment expectations (either text or video), provide different means of representation for the assignment. (See 1.4. Learner–Instructor Connection: Designing Courses With Personality)

- Creating summary graphics for core concepts (e.g., images, tables, flowcharts, etc.) provides multiple means of representation of course content. (See 1.5. Learner–Content Connection: Designing Valuable Learning Experiences)

Creating multiple ways to access content

In this English course, students are provided with multiple ways in which they can engage with a text from an assigned reading. They have the option to listen to an audio of the text, they can read the text, or they can read the text while listening to the audio. The image below is a screenshot for illustrative purposes; no audio is available.

Credit: Suzanne Rintoul, Interdisciplinary Studies, Conestoga College | Image description

Multiple ways to experience content

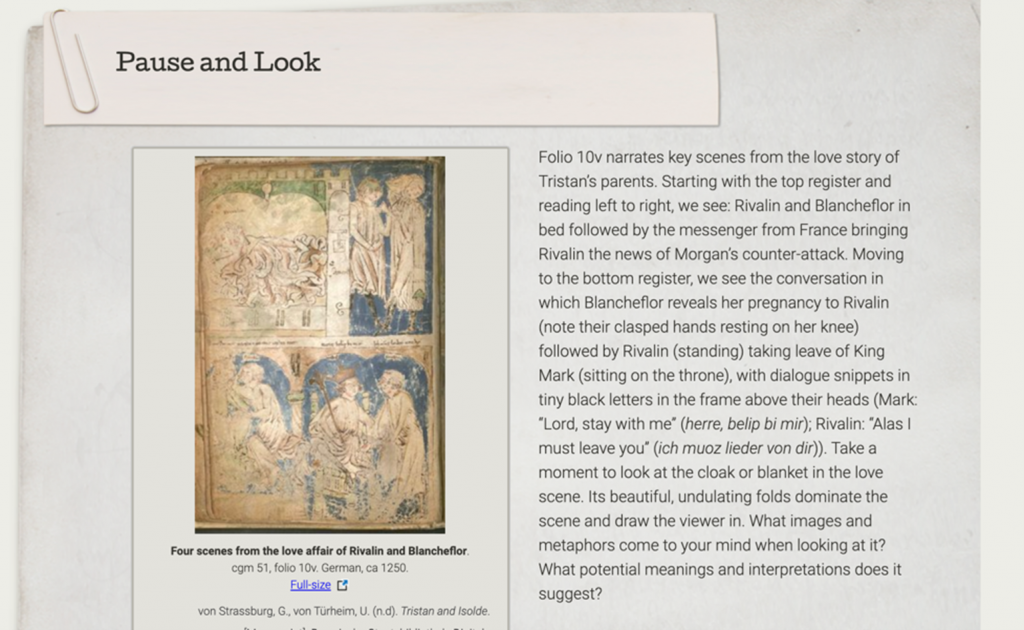

In a German literature and culture course, the course gives learners the opportunity to learn through reading, visually exploring, hearing, and watching.

Reading: the course content is presented on html pages, where the course author guides learners through the readings.

Credit: Ann Marie Rasmussen, German Studies, and the Centre for Extended Learning, University of Waterloo

Listening: while the readings are in English with German translations, the course author reads some sections of the text in German so learners can hear the beauty of the spoken German prose. They also explore other forms of German art in the way of music and opera.

Credit: Ann Marie Rasmussen, German Studies, and the Centre for Extended Learning, University of Waterloo

Visually exploring: Learners are shown images and guided through a text-based visual analysis of the images. Alternative text is provided for all images in the course.

Credit: Ann Marie Rasmussen, German Studies, and the Centre for Extended Learning, University of Waterloo

Watching: Videos and films are also part of the core content in this course. The videos also come with captions.

Credit: Ann Marie Rasmussen, German Studies, and the Centre for Extended Learning, University of Waterloo

Representation in a dementia course

In this open course on dementia, the approach to introducing knowledge and skills related to supporting seniors living with dementia is achieved by presenting learners with several stories of seniors living with dementia. These stories feature seniors with varied lived experiences that provide multiple different opportunities for learners to better understand the experience of seniors living with dementia and through accessible multimedia in a personable and authentic way. This example not only highlights multiple means of representation but also multiple and authentic means of engagement.

Strategies in action: Multiple means of action and expression

With multiple means of action and expression we allow learners to express what they know in different ways and with increasing independence so they can learn to be strategic and goal-oriented.

Examples of multiple means of action and expression from Module 1:

- The “See one, do one, teach one” assessment strategy provides opportunities for multiple means of representation of a course concept, via multiple means of action and expression by the instructor and the learner(s) as well as engagement by the learner(s). (See 1.4. Learner–Instructor Connection: Designing Courses With Personality)

- Providing learners with options in how they want to approach an assignment, which allows learners multiple means of expression.

- Individual advocacy assignment: Gives learners in a neuroscience course choice to follow a more traditional report-style format, or conduct an interview with someone. (See 1.5. Learner–Content Connection: Designing Valuable Learning Experiences)

- Group social intervention assignment: Gives learners in a psychology course the power to choose a topic that resonated with them and they go to choose the final product (intervention format) (See 1.6 Learner–Learner Connection: Designing Authentic Peer Teaching and Learning Opportunities)

Give learners choice in how they demonstrate their learning

In the same German culture course mentioned above, learners are given several different ways to demonstrate their learning, as well as some choice over how their grades will be calculated. The grade breakdown below shows the variety of different assessments and grade weighting. Notice where flexibility and options are provided to learners.

- My Thoughts are short writing prompts that are essentially graded as low-stakes pass/fail assessments designed to get learners writing and help them prepare for the discussions as well as the higher-stakes writing assignments. Learners can choose to skip two of these throughout the term, depending on their workload. This flexibility cuts down on learner requests for extensions and sick notes.

- Discussion reflections are two short discussion profiles, where learners highlight one or two discussions with their peers where they feel good about their contributions and can reflect on their interactions and discussion with their peers. This reduces some of the work of monitoring discussion for the instructor (just checking for participation/completion) and puts learners in charge of deciding which contributions they think best demonstrates their learning. The themes in the discussion are also linked to the writing assignments, so also serve to help prepare students for those higher-stakes assessments.

- Quizzes (three of them) are included in the course as an optional form of interaction, which test learners’ knowledge of content. These also help prepare learners for each of the three writing assessments and are linked to these writing assignments in an important way, which again gives learners some more control over how their learning is assessed. Learners can choose to complete the lower-stakes quizzes, which reduces how much the paired writing assignment is worth. This gives learners who may prefer to demonstrate their learning through tests, rather than writing the option to take a content quiz and reduce the stakes of the paired writing assignment and perhaps reduce some of the stress around these assessments. For learners who are short on time or enjoy writing, they can choose to skip any quiz and take a higher weight on the paired writing assessment. They get to make this choice three times in the course, once for each quiz/writing assignment.

- Writing assignments (three) in this course also provide learners with options in terms of what they write on, and learners should feel prepared to write these assignments, after the scaffolded assessments that lead up to each writing assignment (My Thoughts, discussions reflection, and optional quizzes).

Grade breakdown

The following table represents the grade breakdown of this course.

| Activities and assessments | Weight |

| Introduce yourself discussion board | Ungraded |

| My thoughts (submit 10 out 12) | 10% (10X 1% each) |

| Discussion reflection(2) | 18% (2 x 9% each) |

| Quizzes (3) (optional) | 12% (3 x 4% each)* |

| Writing assignment 1 | 15% (19% if quiz 1 is not submitted)* |

| Writing assignment 2 | 20% (24% if quiz 2 is not submitted)* |

| Writing assignment 3 | 25% (29% if quiz 3 is not submitted)* |

*Each quiz is paired with a writing assignment. If a quiz is not submitted, the weight of the quiz will be added to the corresponding writing assignment.

Credit: Ann Marie Rasmussen, German Studies, and the Centre for Extended Learning, University of Waterloo

Strategies in action: Multiple means of engagement

Multiple means of engagement emphasizes that learners should be stimulated and motivated through multiple means.

(CAST, 2018)

Motivating learners to persist and stay engaged in their learning throughout their online course is an important part of equitable course design.

Examples of multiple means of engagement from Module 1:

- By designing social and content-based interactions and discussions where learners can exchange ideas about core course concepts and extend them to their own lived experiences or connect them to real-world issues, learners understand the intrinsic value of what they are learning and are motivated to engage.

- Peer-to-peer teaching not only allows learners to build a stronger personal connection to the course community, a motivator in itself, but ensures that learners are motivated to understand concepts as they will have to work with/explain them to others. If at the same time we respect the natural life-cycle of learner-learner interactions (socially formative phase, socially instrumental phase, withdrawal phase), we can effectively work with typical learner behaviours to sustain persistent engagement throughout the course.

(See 1.6 Learner–Learner Connection: Designing Authentic Peer Teaching and Learning Opportunities)

Engagement with instructor, peers, and content

The German culture course example above also is an example of multiple means of engagement, as learners had the opportunity for learner–instructor, learner–learner, and learner–content interactions.

Reflect and apply: Setting three UDL goals for your course design

Based on what you have learned in this section regarding the principles of universal design for learning (UDL), write down three goals to increase the accessibility of your course to all learners. With each goal, you will also write three tasks or brainstorm three ‘next steps’ to help chart a path to achieve your UDL goals.

Remember, you are not alone! The principles of UDL can be sometimes challenging to envision in terms of what it may look like in practice. Don’t be afraid to discuss with your colleagues their experiences and best practices in this area or access accessibility centres or centres for teaching and learning at your institution for guidance and support.

How to complete this activity and save your work:

Type your response to the questions in the box below. Your answers will be saved as you move forward to the next question (note: your answers will not be saved if you navigate away from this page). Your responses are private and cannot be seen by anyone else.

When you complete the below activity and wish to download your responses or if you prefer to work in a Word document offline, please follow the steps below:

- Navigate through all tabs or jump ahead by selecting the “Export” tab in the left-hand navigation.

- Hit the “Export document” button.

- Hit the “Export” button in the top right navigation.

To delete your answers simply refresh the page or move to the next page in this course.

References and credits

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Pulrang, A. (2013, August 17). Accessibility vs. accommodation. Disability Thinking. http://disabilitythinking.blogspot.com/2013/08/accessibility-and-accommodation.html

Sapon-Shevin, M. (2007). Widening the circle: The power of inclusive classrooms. Beacon Press.

Thompson, G. (2018, October 2). What is the AODA? Accessibility for Ontarians with Disability Act. https://aoda.ca/what-is-the-aoda/

Thompson, G. (2019, August 26). AODA requirements for educational institutions. Accessibility for Ontarians with Disability Act. https://www.aoda.ca/aoda-requirements-for-educational-institutions/