Module 2: Designing for inclusivity

2.3 Social justice in virtual learning contexts

Key principles: Seeing identity and frames of social justice

Educationalist Parker J. Palmer (1998) posits that as designers and instructors of post-secondary education (PSE) experiences we cannot help but “teach who we are” (p. 2).

If students and subjects accounted for all the complexities of teaching, our standard ways of coping would do—keep up with our fields as best we can and learn enough techniques to stay ahead of the student psyche. But there is another reason for these complexities: we teach who we are.

(Palmer, 1997)

Working from Palmer’s assertion, it stands that where EDDI interfaces with issues of social justice and virtual teaching and learning, it is important that virtual learning designers have the capacity to and make time for self-reflection on their own positioning in relation to an ever-developing range of social justice frames and identities because those personal and professional positionings cannot help but become part of their course designs.

Definitions

Identities: groups or broad communities with which individuals might self-identify. For instance, members of the 2SLGBTQ+ community, Indigenous Peoples, environmental activists, cisgender women, or White men.

The last two examples are identities that generally experience privilege on one or more of the listed identities; these are legitimate identities that often become invisible as a result of the privilege that they experience.

Frames of social justice: social justice issues that have some degree of objective criteria for establishing membership, like socioeconomic status, older adults, or level of education (no high school diploma, high school graduate, advanced degree-holder, etc.). Individuals may or may not self-identify with a social justice frame, even if they fit the objective framing criteria.

In this section, we will engage with an exercise that helps us to reflect on our own social justice positioning relative to privilege and oppression so that we might develop some insight into how this manifests in the learning experiences that we design and deliver. Then, we will offer a high-level overview of a number of important social justice frames and identities, and look at how those aspects of social life intersect in complex ways. Finally, we’ll explore some practical strategies for humanizing learning across the range of social justice identities and frames.

Key principles: Understanding privilege and oppression

As designers of online courses, postsecondary faculty and academic support unit (ASU) staff hold positions of privilege within their professional context. As decision-makers about course content and structure, faculty and ASU staff exercise power as they make choices about how learners will experience virtual learning environments, and that power can have a significant “ripple effect” into all aspects of a learner’s life—emotional, social, financial, political, etc. While some people may experience a sense of discomfort or even shame associated with the suggestion that they occupy a privileged position, an important first step in humanizing learning experiences involves acknowledging the multiple and dynamic ways that educators experience both privilege and its opposite: oppression.

Acknowledging and naming privilege and oppression allows for the development of awareness of the kinds of ways that being privileged/oppressed impacts life experiences both broadly, and in the specific context of formal education. This acknowledging and naming is also a keystone aspect of both social justice and humanizing learning.

Note

The word oppression can seem strange in our contemporary society, as for many people it holds connotations of obvious, visible cruelty, or mistreatment. In modern western societies, however, the nature of oppression has shifted such that oppression functions structurally, meaning that people experience oppression as they interact with social systems (like education, social services, financial institutions, healthcare agencies, etc.) in ways that may not be obvious to other people who are not experiencing oppression, or not experiencing it in the same way or to the same degree.

By being more aware of their position within a social field of privilege and oppression, a course designer is in a position to leverage the privilege associated with their professional responsibility for course design. Through the process of course design they can make choices that help to break down status-quo aspects of privilege and oppression in their courses, and foster greater equity through taking steps to humanize learning in their virtual course.

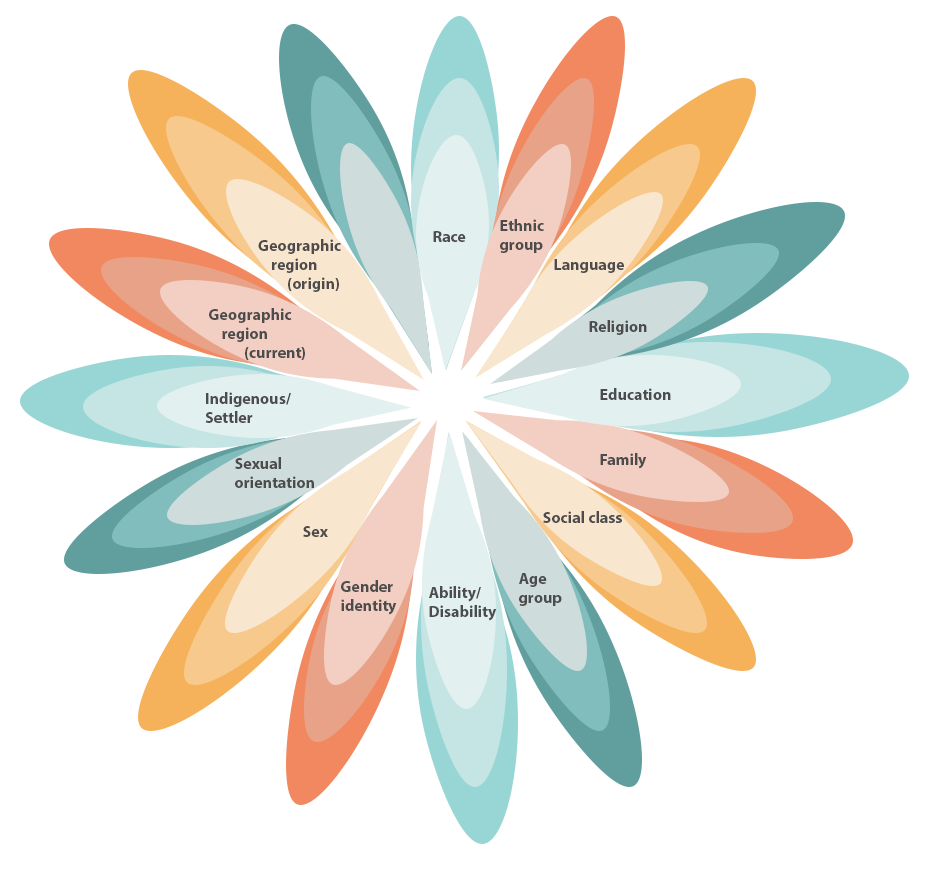

Key principle: Social justice self-reflection – The power flower

Self-assessment of privilege and oppression is a critical skill for course designers who aim to design courses that are responsive to social justice considerations. By self-assessment, we mean the ability to take inventory of the many ways that one experiences privilege or oppression in their own personal and professional life, in order to better understand how that privilege, through knowledge assumptions and other biases, may inadvertently be transferred into the design of online learning experiences.

One exercise for undertaking an inventory of personal and professional privilege is the power flower (Arnold et al., 1991). Designed in the early 1990s by a group of social justice educators, this activity asks participants to consider their own positioning relative to the dominant group across a range of social justice categories. By dominant group, we mean the social and/or cultural group that holds and maintains social and economic decision-making authority in a society or community.

Categories of social identities and frames include the following:

- race

- ethnic group

- language

- religion

- education

- family

- social class

- age group

- ability/disability

- gender identity

- sex

- sexual orientation

- indigenous/settler

- geographic region (current)

- geographic region (origin)

- a blank space left for the user to insert any categories that are relevant to their identity, but that weren’t considered by the activity developers

Credit: Adapted from Albert, Burke, James, Martin, & Thomas (1991), and Lee (1985).

To use the power flower, consider each element of social justice identity, and on the outside flower petal, indicate the nature of the dominant social group for this category (for example, in the category of race, White is likely to be the dominant group). Then, on the inside flower petal, indicate your personal identification for the given category. It may be helpful to colour code dominant and non-dominant group status to give visual power to the exercise.

It is important to remember when completing the power flower that on any given petal of the flower, a match or mismatch between one’s interpretation of the dominant group and one’s own positioning doesn’t necessarily indicate the de facto existence of oppression; an individual must reflect on their own experience to determine if they experience oppression.

Strategies in action: Power flower exemplar

To provide a concrete example of social justice self-assessment, one of the module co-authors, Blair Niblett, (Associate Professor, Trent University) offers his own completed self-assessment as an exemplar. After reviewing his completed power flower, Blair offered his reflection. Click the quote icon below to view his reflection.

As we can see from this exemplar, the simple exercise that is the power flower can be powerful and complex in terms of its capacity for enabling reflection on experiences of privilege and oppression.

Reflect and apply: Your own power flower

Using the downloadable power-flower template file (.docx or .pdf, so you can work offline on your computer or on paper), Power-Flower Activity (DOCX), consider your own identity in relation to the dominant group for each social justice category.

Guidance:

- Try not to rush through this exercise.

- Take time to think carefully about who you are as a person and an educator, where you come from (socially and geographically), and how you relate with the dominant group on each category of the flower diagram. This might be informed by your own experiences of disadvantage or exclusion related to social identities or social justice frames identified on the power flower, or not.

- It is perfectly fine if there are some aspects of social identity that you’re not sure how to complete. Simply fill in your best understanding of a dominant group, and your own identity for that aspect. You may choose to come back to this activity and update your thinking about dominant groups and your own positioning as you move through the module, or the rest of this course.

You will note that you are able to fill in a dominant group for each flower petal. While as course designers we could have filled this into the template, we have opted not to do so for two reasons.

- First, acknowledging and naming a dominant group is an important part of the exercise that we want learners to participate in.

- Second, some of the social identity petals have dominant groups that are regionally contextual, meaning that people in some places would reasonably choose a different dominant group.

- Beware of “reverse” oppression. If you are a dominant group member, it may be the case that you have experienced discrimination at some point in your life related to your dominant group membership. While any level of discrimination may have led to negative impacts or bad feelings for you, this kind of exclusion is not considered oppressive because it is not backed by a historical or pervasive power imbalance, as is the case for oppressed groups (e.g., racialized people, 2SLGBTQ+ people, women, etc.) (Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2012).

Download the Power-Flower Activity (DOCX).

Now that you have completed the power flower exercise, reflect on your experience of the exercise, and answer the two questions in the interaction below.

How to complete this activity and save your work:

Type your response to the questions in the box below. Your answers will be saved as you move forward to the next question (note: your answers will not be saved if you navigate away from this page). Your responses are private and cannot be seen by anyone else.

When you complete the below activity and wish to download your responses or if you prefer to work in a Word document offline, please follow the steps below:

- Navigate through all tabs or jump ahead by selecting the “Export” tab in the left-hand navigation.

- Hit the “Export document” button.

- Hit the “Export” button in the top right navigation.

To delete your answers simply refresh the page or move to the next page in this course.

Note: Social justice, as a part of humanizing learning, requires a lot of reflection on identity that can be intimate and personal. You may also leave these fields blank and record your responses elsewhere on your own device, or in your own offline journal or notebook.

Going deeper

The Wheel of Privilege, developed by the Intertwine Charter, offers a similar model to the power flower, but with additional categories and some greater emphasis on the intersectionality between social justice identities and frames (intersectionality is a concept we will explore further later in this module).

Why a flower?

You may wonder about the significance of the symbol of the flower in this exercise.

While the original designers of the activity were not explicit on why a flower was chosen, we posit three valuable reasons that the flower is a useful metaphor:

- The arrangement of interior and exterior petals in the flower illustrate that individuals exist within social systems that are controlled by a dominant social group (Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2012).

- The circular arrangement of the petals representing aspects of social identity means that the list of aspects is not hierarchical. This is important because a simple listing might convey an order of importance among markers like race, social class, and age group. Such an arrangement is not appropriate in the abstract; only an individual can decide the relative importance of each social identity in their own life.

- The arrangement of petals around a central point shows that each of the social identities exists in relation to the other aspects of identity. In other words, each aspect is not fully independent, but rather intricately connected to the other aspects also connected to the central hub of individual identity. This last point is a description of a concept often called intersectionality, (Crenshaw, 1989) which has become a popular term to describe the complexity of occupying multiple social identities that fall outside the dominant group for that aspect of social identity.

Key principles: Understanding intersectionality

As we noted above, the power flower is elegant in its design because it conveys a non-hierarchical and inter-related construct of multiple identities of privilege and oppression that any individual might subscribe to. A foundational concept for understanding this dynamic arrangement is Kimberlé Crenshaw’s notion of Intersectionality.

Definitions

Intersectionality: a concept developed by Black, feminist, legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989) to explain a compounding or multiplying effect experienced by people who occupy more than one identity or frame of oppression. In Crenshaw’s (2017) own words: “Intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects. It’s not simply that there’s a race problem here, a gender problem here, and a class or LBGTQ problem there. Many times that framework erases what happens to people who are subject to all of these things.”

In Crenshaw’s analysis, the multiple-burden is generally being both Black and a woman, though Crenshaw and others have expanded the notion of intersectionality to include the full range of identities explored here.

Because the intersectional experience is greater than the sum of racism and sexism, any analysis that doesn’t take intersectionality into account cannot sufficiently address the particular manner in which Black women are subordinated. Thus, for feminist theory and antiracist policy discourse to embrace the experiences and concerns of Black women, the entire framework has been used as a basis for translating ‘women’s experience’ or ‘the Black experience’ into concrete policy demands must be rethought and recast.

(Crenshaw, 1989, p. 140)

In the following video segment, Crenshaw illustrates the concept of intersectionality in clear terms. Also, pay attention to her articulation of the relationship between intersectionality and the context of multiple identities that are rooted in history and in the context of community.

Transcript for Kimberlé Crenshaw: What is Intersectionality? available on YouTube.

Credit: Kimberlé Crenshaw, 2018

Key principles: Aspects and intersections of social identity

Thus far, we have asked you to consider the aspects of social identity without providing any specific information about each one. Many adults have an implicit understanding of various social identities because we have inhabited and encountered them all our lives. However, especially for those who identify as members of a dominant group, it is possible for social identities to be an invisible aspect of our existence. Therefore, it can be helpful to have an explicit understanding of what each one is.

In this course, there isn’t time or space to explore each of the aspects of social identity with any depth; in fact, each aspect could take up an entire course of its own! Still, humanizing online learning calls on educational designers to have a basic working understanding of social identity aspects by which people might experience privilege or oppression.

Here we will offer a quick look at each of the aspects identified in the power flower. For each of the frames or identities, we’ll also name the ‘ism’ or kind of oppression that emerges in relation to the aspect of identity and offer some relevant information for that frame/identity within the context of post-secondary education (PSE).

Human dimension and caring

Knowledge of social identities and frames better enable virtual course design that responds to the human dimension and caring aspects of Fink’s taxonomy of significant learning (see 1.3. Setting the Stage for Significant and Courageous Learning).

Social identities, complexities, oppression, and the postsecondary context

In this power-flower interactive, you have the opportunity to dive a little deeper into each of the petals (social identities) in the power flower.

You can click through each of the identities listed in the left-hand navigation or choose to focus on a few that are of most interest to you. Each social identity is defined, some of the complexities associated with it are explored, as are forms of oppression and specific relevance to the PSE context.

Within this power flower interactive, we offer many “Going Deeper” resources to allow you to explore each concept of social identity and privilege/oppression more thoroughly. These possible areas for learning are an extension of this course but are not all required to achieve its learning outcomes. We suggest that you select one or two social identity categories for which to engage with the “Going deeper” resources, but you are welcome to explore as few or as many as you like based on time available to you.

Strategies in action: Social identity and justice through virtual course interactions

To introduce strategies for designing online learning experiences that are responsive to social justice elements of EDDI, we return to Parker J. Palmer’s (2017) assertion presented at the outset of this section that “we teach who we are.”

An important extension of Palmer’s missive is that while teaching strategies, engagement techniques, specialized resources, and innovative technologies may all play a role in designing high quality online learning experiences; designers and instructors are often too quick to reach for these kinds of external approaches for engaging learners and overcoming EDDI challenges, and too hesitant to look inward as an educator to overcome course design and implementation challenges through broader and deeper understandings of self across the range of social identities and frames that we have discussed above.

Following the logic of Palmer’s “we teach who we are” assertion, the work that has been undertaken in this section—completing the flower of power exercise, and exploring some of the “going deeper” resources related to social justice is a strategy of paramount importance in forwarding EDDI objectives in PSE. Still, we appreciate that the identity clarification work that has been taken up in this section is perhaps a less practical a strategy than designers might need to begin taking immediate action toward humanizing online learning.

With that in mind, we offer a few ideas below for concrete actions to humanize online learning by addressing social justice, across the three primary interactions of online learning. Be aware, however, that these strategies are likely to be more impactful in humanizing learning when used by a designer/educator who is working to develop self-awareness in relation to social justice privilege and oppression.

Strategies in action: Remind yourself and learners of your social justice commitments

In Module 1, we introduced Michelle Pacansky-Brock’s idea of a liquid syllabus, in which the instructor introduces themselves to learners in a more personal and less formal sense than is typically accomplished in the formal course syllabus. The liquid syllabus would be an excellent place to lay out commitments that you have to social justice principles. Consider situating your own identities of privilege and oppression, and commit to delivering the course in ways that promotes equity across all social injustices.

Additionally, frame yourself as a learner in relation to social justice. Especially if you occupy identities of privilege, positioning yourself as open to ongoing learning about marginalized identities may help learners who experience marginalization to view you as an ally.

A note on being an ally

Allyship is a fraught concept in social justice circles. Even when a person of privilege does excellent work in supporting communities experiencing social injustice, we suggest caution in publicly naming oneself as an ally. Taking on that label often serves to benefit the person of privilege more than those who they are allied to. The role of ally is best acknowledged and assigned by individuals who experience marginalized identities and frames.

Strategies in action: Social justice reading list, resource, and image audit

Social justice reading list and resource audit

Historically, reading lists and resources used in PSE have largely been made up of texts and materials created by men (Harris et al., 2020). We hypothesize that this bias in reading lists likely extends to many other aspects of social justice (race, sexuality, etc.).

When designing or redesigning an online learning experience to humanize learning, conduct an audit of the reading list or other resources used to deliver the learning outcomes to determine what social identities are represented in the creators of the texts and resources used to deliver the course.

Ask yourself the following questions:

- Are there authors on my reading list who represent Black, Indigenous, and/or people of colour?

- Are there 2SLGBTQ+ authors represented?

- Are there authors who experience disability?

Then, seek out readings and resource materials authored by diverse scholars and/or professionals who represent various social justice frames and identities. Each text that is included in a course that presents work from an author who represents a marginalized social group creates a potential opportunity for learners who occupy marginalized identities (racialized, 2SLGBTQ+, disabled, etc.) to see themselves in the course materials from which they are learning. This possibility represents a significant step towards humanizing virtual learning.

Credit: This exercise is inspired by Dr. Denise Handlarski and Dr. Karleen Pendleton Jimenez, School of Education, Trent University.

Going deeper

To understand the type of audit process one might undertake when redesigning a course, Dr. Walker, provides her experience in undertaking a redevelopment of a traditional undergraduate Eurocentric music course into one that was more global and inclusive in its scope. Her redesign was underpinned by data from a scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) project where Dr. Walker studied student perceptions of music and music history.

Transcript for Showcase 2021: Remote Opportunity for Inclusive Music History is available on YouTube.

Credit: Margaret Walker, 2021

Social justice image audit

Following an audit of your reading list, repeat the same steps for images that are included in your virtual learning designs.

Do the images in your design

- show range across the gender spectrum?

- illustrate gender in ways that do not reinforce binary (male/female) gender stereotypes (unless the purpose is to intentionally question gender stereotypes)?

- include racialized individuals equitably, and in ways that do not perpetuate racial stereotypes?

- include people with disabilities and different types of disabilities (e.g., other than physical disability requiring a wheelchair)?

- avoid stereotypes representations of social roles or professions?

- consider what power dynamics are implied between individuals in an image and ensure they do not perpetuate stereotypes?

Strategies in action: Create space for learners to talk about and act on issues of social justice

Given the opportunity and a little bit of encouragement, most learners are excited to talk about social justice and their own experiences. Issues of social justice crosscut our lives, and so it should be possible to integrate social justice learning within the broader context of learning in an online course in any academic discipline. Blogs, discussion boards, wikis, and other interactive tools in your LMS may be ways to enable learner interactions around issues of social justice.

When designing these course elements,

- encourage inquiry through questioning: Plan to begin a dialogue with a question rather than a statement of belief or position, as this may promote a more open exchange of ideas. Encouraging learners to pose questions “to the room,” as opposed to a specific individual, may also promote collegial exchange and avoid putting specific individuals “on the spot” in virtual discussions;

- encourage real-world action, even on a small scale: Online dialogue around social justice can be especially impactful if it is related to real-world actions that learners take in their own communities. If your course extends over weeks or months, consider adding (or modifying) an assignment such that learners are asked to identify a social justice issue that is important to them, observe that issue in their community, and design an intervention—even one that is tiny in scale or scope. Online dialogue can then become a check-in place for reporting back on developments, setbacks, or key learnings from their local community engagement. For an example, look back to the scaffolded assignments section in Module 1.4: Strategies in Action: Modelling and Inspiring Connections With Your Learners.

- discourage debate that calls into question the existence or seriousness of social marginalization or oppression: Framing debates about social justice can lead to denial of conditions of privilege and oppression that do not serve the aims of humanizing virtual learning; and

- recognize that learner dialogue around issues of social justice requires close instructional team facilitation: This is to ensure that the intention of inclusive learning is realized, and that oppressive conditions (sexism, homophobia, ableism, etc.) are not reinforced through learners’ posts and replies. Of course, sexist, racist, or other oppressive comments could arise in any learner-learner interaction, but interactions related specifically to social justice may be more likely to give rise to intentional or unintentional comments that work against the aims of humanizing learning. In Module 4, we offer more comprehensive guidelines to serve as ground rules for virtual discussion, but it is important to think about this at the design phase to ensure you, TAs, or other instructors of your course will have the time and resources to engage in these discussions with your students.

In designing community action projects and course dialogues, faculty and ASU staff are not alone! Connect with staff in a teaching and learning centre or community-based learning centre at your institution for support and advice on successfully leveraging community action and dialogue to humanize learning.

References and credits

Airton, L. (2018). Gender: Your guide. A gender friendly primer on what to know, what to say, and what to do in the new gender culture. Adams Media.

Alper, L. (Director), & Lesityna, P. (Producer). (2005). Class dismissed: How TV frames the working class [Film]. Media Education Foundation.

Arnold, R., Burke, B., James, C., Martin, D., & Thomas, B. (1991). Educating for a change. Between the Lines and the Doris Martin Institute for Education and Action.

Card, D., & Payne, A. A. (2015). Understanding the gender gap in postsecondary education participation: The importance of high school choices and outcomes. Higher Education Quality Council of Canada. https://heqco.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Gender-Gap-ENG.pdf

Council of Ontario Universities. (2018). Student voices on sexual violence climate survey, demographics breakdown report. https://www.ontario.ca/page/student-voices-sexual-violence

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139–168.

Crenshaw, K. (2017, June 8). Kimberlé Crenshaw on intersectionality, more than two decades later. Columbia Law School Story Archive. https://www.law.columbia.edu/news/archive/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality-more-two-decades-later

Edge, J., Kachulis, E., & McKean, M. (2018, April 19). Gender equity, diversity, and inclusion: Business and higher education perspectives. Conference Board of Canada. https://www.conferenceboard.ca/e-library/abstract.aspx?did=9620

Frideres, J. (2015). Being White and being right: Critiquing individual and collective privilege. In D. E. Lund & P. R. Carr (Eds.), Revisiting the great White north? Reframing Whiteness, privilege, and identity in education (2nd ed., pp. 43–53). Sense.

Golash-Boza, T. M. (2018). Race and racisms: A critical approach (2nd Ed.). Oxford University Press.

Harris, J. K., Croston, M. A., Hutti, E. T., & Eyler, A. A. (2020, October 28). Diversify the syllabi: Underrepresentation of female authors in college course readings. PLOS ONE, 15(10), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239012. Used under CC BY 4.0 license.

Jaschick, S. (2018). Race and gender bias in online courses. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/03/08/study-finds-evidence-racial-and-gender-bias-online-education

Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an anti-racist. One World.

Lee, E. (1985). Letters to Marcia: A teacher’s guide to anti-racist education. Cross Cultural Communication Centre.

McIntosh, P. (1989, July/August). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. Peace and Freedom Magazine, 10–12.

Palmer, P. J. (2017). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life (20th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Policy Options. (2007). Mind the access gap: Breaking down barriers to post-secondary education. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/ontario-2007-dalton-mcguinty/mind-the-access-gap-breaking-down-barriers-to-post-secondary-education/

Sapon-Shevin, M. (2007). Widening the circle: The power of inclusive classrooms. Beacon Press.

Sensoy, O., & DiAngelo, R. (2012). Is everyone really equal? An introduction to key concepts in social justice education (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Zook, M., Chan, K. B. K., Chabot, F., & Neron, B. (2017). Beyond the basics: A resource for educators on sexuality and sexual health (3rd ed.). Action Canada for Sexual Health and Rights.