Case: Superfood Advertising

Anne F. MacLennan and Irena Knezevic

Anne F. MacLennan is an Associate Professor in Communication and Media Studies at York University and editor of the Journal of Radio and Audio Media. She is co-author of Seeing, Selling, and Situating Radio in Canada, 1922–1956. Her research focuses on radio, media history, research methodologies, women, poverty, advertising, and labour. She is published in Media and Communication,Journal of Radio & Audio Media,Women’s Studies, Radio Journal, Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations,Urban History Review, and edited collections.

Irena Knezevic is an Associate Professor in the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University, and the director of the Carleton Food and Media Hub. She is a co-editor of Nourishing Communities: From Fractured Food Systems to Transformative Pathways and has published in CanadianJournal of Communication, Canadian Food Studies, Food, Culture and Society, and Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development.

Learning Outcomes

After reading and discussing this text, students should be able to:

- Identify some advertising strategies used to promote commercial food products.

- Describe historical precursors of “superfood” advertising.

- Articulate links between food, health, and advertising.

Introduction

Many cultures have versions of the sayings, “you are what you eat,” “a hungry person is an angry person,” and “let food be thy medicine.” Food, health, and well-being are inextricably linked, and advertising has long capitalized on this.[1] Promotional messages that describe food products as linked to diets, low in undesirable ingredients like added sugars, or high in desirable ones like fiber, always imply that such products improve health. While those qualities can be beneficial to human health, their impact is sometimes exaggerated as a magical solution to the pursuit of health and well-being.

In much of the world, the average person is exposed to thousands of advertisements every day. People receive information from advertising, alongside nutritional advice from news media, social media feeds, science reporting, and public health messaging. Competing interests, evolving nutritional science, and cultural trends shape the abundance and the complexity of available food information. That information is now made widely accessible with new media technologies, which have also enabled anyone—not just recognized experts—to offer opinions and recommendations to tell consumers how to choose their food. This—rather than making us more knowledgeable about nutrition—leaves us sifting through conflicting and confusing messages looking for shortcuts to wise food choices. We want simple, magical solutions to health and well-being. This desire is bolstered by promotional messages that highlight individual responsibility for personal health. Health and nutrition are often portrayed as individual choices, encouraging those practices that are deemed healthy as moral imperatives. Even for people who have little choice—for economic, mobility, geographical or other reasons—this view imposes a cultural norm of individual responsibility for managing diet and appearing healthy. Food products that promise to aid in dietary management benefit from this cultural norm.

The Bovril Example

In 1871, butcher and amateur food scientist John Lawson Johnston acquired the contract to supply canned meat to Paris after the Franco-Prussian War. Commercial production of his meat-extract paste commenced in Montreal in 1874.[2] The product was soon available widely and continues be sold to this day. The international promotion of Bovril in the early twentieth century offers a fascinating glimpse into the historical trajectory of food advertising that promises “health, strength, and happiness.” Bovril advertising evolved, but the core message has remained consistent—this food product offers an easy, convenient path to well-being through consumption.

We have been collecting and analysing Bovril advertisements for more than a decade. The product’s century-and-a-half long existence has generated hundreds of advertisements; many from the early 20th century are widely available in physical and digital archives.

A more focused sample from 1930 to 1940 was collected from major Canadian newspapers,[3] where a keyword for Bovril produced a sample of unique 288 advertisements. The decade of the Great Depression was a time of post–World War I recovery and unstable global politics that would eventually lead to World War II. It was also a decade of food precarity that made a meat substitute like Bovril more significant. Moreover, the early 1900s are considered the golden age of advertising, when transportation and printing technologies speedily evolved, and industrialization allowed for large-scale production and expansion of markets outside of manufacturers’ local communities. However, by the mid-1920s in North America, print media suddenly had to compete with radio for advertising revenue, and in response, print ads became increasingly catchy, intricate, and colourful. The archives from the decades that followed offer an abundance of diverse and clever print ads.

Health and Strength

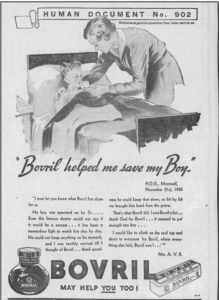

A close reading of the advertisements revealed that science, medicine, and health figured heavily in the campaigns. In the advertisement, “Yes, Doctor – Bovril is just what he needed” (Figure 1), a nurse is on the telephone. Bovril sits outside of the frame of her photograph, connecting it to the nurse and her report to the doctor. The advertisement’s claim that “Bovril Gives Strength Quickly” is expanded, indicating its “unique power of enabling convalescents to get more nourishment from other foods.”[4] Bovril’s Human Document campaign offered testimonials attesting how Bovril improved customers’ health. “Bovril helped me save my Boy” (Figure 2) chronicled a Montreal mother’s story about her worries after her son’s surgery, proclaiming “I would…shout to everyone ‘try Bovril, when everything else fails, Bovril won’t…’”[5] The campaign, with its numbered “document” entries, implied research-based evidence of Bovril’s success. This was at a time when scientific innovations, acceptance of germs, and the ability of people to influence their own health through practices like exercise, diet, anti-spitting laws, and initiatives other than prayer became important. Montreal, Canada’s largest city in the 1930s, was second only to Mumbai in tuberculous infections in the 1920s and 1930s.[6] Public health campaigns of the time worked to change traditional practices of sanitation and health.[7] In Canada, 1926 to 1930 infant mortality rates averaged 93 per 1000 live births, 75 from 1931 to 1935, and 64 from 1936 to 1940, making the health of surviving children a pressing concern.[8] Pablum, a prepackaged, vitamin-enriched cereal for children developed by Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children, is an example of a dietary innovation used to strengthen the body during an era when other remedies failed to safeguard children against polio, Scarlett fever, tuberculosis, measles, rickets, and other diseases.

- Figure 1: Bovril gives strength quickly

- Figure 2: Bovril helped me save my Boy

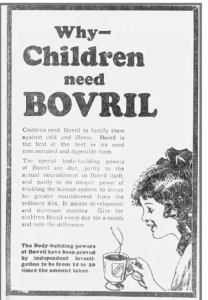

- Figure 3: Children need Bovril

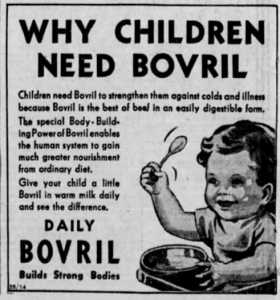

- Figure 4: Why children need Bovril

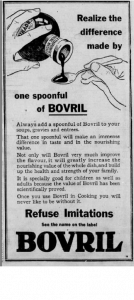

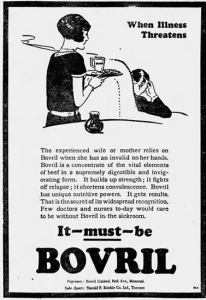

Echoing the concerns about childhood health, the campaign “Why Children Need Bovril” (Figures 3 and 4) featured toddlers and older children. It promoted Bovril’s “body-building powers” and encouraged parents to mix Bovril into milk and add it to their children’s daily diets.[9] The promotion of the body-building characteristics of the product extended to adults emphasizing “remarkable experiments upon human subjects” and the “astonishing body-building power of Bovril proved by famous Physiologist.”[10] The appeal to scientific research and medical authority in text was paralleled by visuals. “Realize the difference made by one spoonful of Bovril” (Figure 5) incorporated an image of Bovril being poured into a spoon like medicine.[11] While no medical claims were made in the advertisement, the daily use of Bovril was promoted. “It must be Bovril” (Figure 6) became the catchphrase of a Bovril campaign, reportedly quoting Sir Ernest Shackleton preparing for his Antarctic Expedition. Bovril was described as essential for homes and sickrooms attended by doctors and nurses.[12] The association with strength and health extended well into the 1970s with testimonial advertising from mountaineers[13] and elite athletes.[14] Health remained a constant element in the campaigns. While the imagery and text changed to reflect the sensibilities of each decade, Bovril advertising repeatedly featured notions of health, medicine, and science, over several decades.

- Figure 5: One spoonful of Bovril

- Figure 6: It must be Bovril

Magic and Transformation

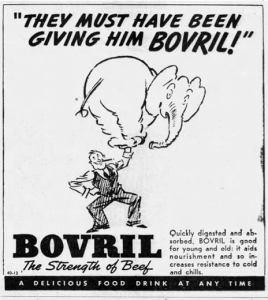

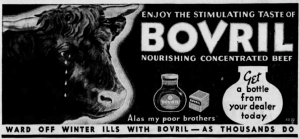

Magical, physical, and mental transformation was always a strong component of Bovril campaigns.[15] Canadian 1930s advertising portrayed Bovril as a comforting, hot drink, especially in the winter. The power of beef in the formula was credited with great feats of strength, such as the man in office attire holding an elephant above his head (Figure 7).[16] Advertising the power and stimulating taste of Bovril was crucial in a period when regular access to protein through meat was precarious. Concentrated beef was a key selling point in the advertisements, and the bull, a symbol of strength and authority (Figure 8), was a reminder of this ingredient and what it promised to deliver.[17] Avoiding the chills and ills of winter were routinely part of the advertising, whether it featured a sick or injured person, or outside gatherings. Further, meat was expensive and at the same time considered a necessity for nourishment and strength.[18]

- Figure 7: They must have been giving him Bovril

- Figure 8: Enjoy the strength of Bovril

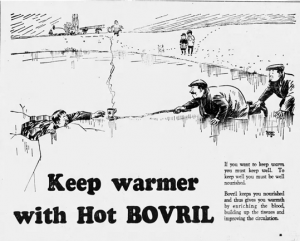

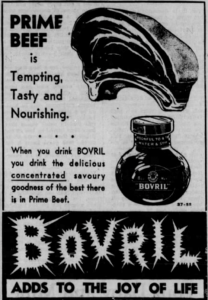

In the advertisement “Keep warmer with Hot Bovril” (Figure 9) the association with the heroic continued, with two men rescuing another man, who had fallen through ice, by offering him a hot cup of Bovril rather than pulling him from the icy water.[19] The magical qualities were reinforced with the image of a large cut of prime beef hovering over the tiny bottle of Bovril to show all the “concentrated savoury goodness of the best there is in Prime Beef” (Figure 10) packed into the small bottle.[20]

- Figure 9: Keep warmer with Hot Bovril

- Figure 10: Bovril is Tempting, Tasty, and Nourishing

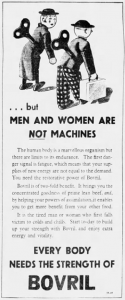

T.J. Jackson Lears, a cultural historian, argues that industrialization ushered neurasthenia, a type of depression associated with changes wrought by the modern working world.[21] Bovril captured that early-20th-century concern for mental health and well-being in its “Bovril Prevents that Sinking Feeling” campaign, and in advertisements such as “…but men and women are not machines… Every Body Needs the Strength of Bovril” (Figure 11).[22] Bovril’s advertisements illustrated the constant work, including women’s unending work (Figure 12), and the euphemistic visualization of sinking represented by a man clinging to a buoy at sea. Along with advertisements demonstrating physical strength to ward off physical illness, these showed how Bovril could make life brighter, as a cure and remedy, but also as a daily treat. It was promoted as an ingredient in soups and stews, mixed with milk, or as a sandwich spread (Figure 13).[23] Health, well-being, and Bovril were linked as a daily routine.

- Figure 11: Men and women are not machines

- Figure 12: A woman’s work is never done

- Figure 13: Bovril sandwiches

Discussion, implications, and conclusion

Advertising equates the purchase of food with a sense well-being and overall good health. Recent promotions of “superfoods” are examples of promotions that echo the tone of early Bovril advertising. In recent years, many foods like acai berries products, green tea, and fermented milk, like kefir and “probiotic yogurt,” have been touted as superfoods that can instantly improve health and extend lifespan. In 2021, OSU, owned by Mizkan in Japan, launched a campaign to promote its apple cider vinegar in the U.K. market. It cast three stylish nonagenarians from Tokyo to convey vitality and health.[24] The eternal quest for health and happiness continues to feature prominently in advertising.

Social theorists have long identified the link between dietetic management and capitalism. Bryan Turner[25] proposed that dietetic management of one’s body stemmed from two key characteristics of capitalism: (a) the privileging of Western science and medicine, and (b) the need for functioning, labouring bodies to participate in industrial commodity production. Mike Featherstone[26] expanded on this to include another tenet of capitalism—individualism. The emphasis on individual freedoms and responsibilities has made “body maintenance” both an individual responsibility and a requirement for economic participation. Together, these values have rendered dietetic management a pillar of being a good citizen.

The resulting cultural pressure on individuals to pursue “good” diets makes promises of easy solutions to healthy eating particularly appealing. Bovril’s longevity on the market suggests that their messaging has resonated with consumers, serving as a historical example of successful food advertising.

Contemporary advertising for various “superfoods” is but a continuation of promotional messaging that offers shortcuts to dietetic management. Bovril’s 1930s advertisements may seem laughable now, but a closer reading reveals that they were also trailblazing.

Discussion Questions

- How do current advertising campaigns convince consumers that their foods make them healthy and happy?

- What advertising messages have prompted you to buy a food product to improve your health?

- What do historical examples of food advertising tell us about the evolving understandings of health and nutrition?

Additional Resources

Readers can find numerous Bovril print and television ads with a simple internet search. Bovril even has its own Wikipedia page!

Product information about Bovril is available on the manufacturer’s website.

John Lawson Johnston’s papers are held by the City of Edinburgh Council Archives.

References

Adams, A., K. Schwartzman and D. Theodore. 2008. “Collapse and Expand: Architecture and Tuberculosis Therapy in Montreal, 1909, 1933, 1954.” Technology and Culture 49 (4): 908–942.

Bovril. “Bovril helped me save my Boy.” Advertisement. The Vancouver Sun. November 19, 1937, p. 7.

Bovril. “Bovril stands alone”. Advertisement. Vancouver Daily World. October 22,1920. p. 16.

Bovril. “Enjoy the stimulating taste of Bovril nourishing concentrated beef.” Advertisement. The Vancouver Province. December 14, 1938. p. 32.

Bovril. “Keep warmer with Hot Bovril.” Advertisement. The Ottawa Citizen. December 1, 1930. p. 17.

Bovril. “Men and Women are Not Machines” Advertisement. The Ottawa Citizen. February 1, 1940. p. 7.

Bovril. “Prime Beef is tempting, tasty, and nourishing.” Advertisement. Regina Leader-Post. January 5, 1938. p. 16.

Bovril. “Realize the difference made by one spoonful of Borvil.” Advertisement. The Regina Leader-Post. November 5, 1931. p. 4.

Bovril. “Tempting and Tasty Bovril Sandwiches are so delightfully different.” Advertisement. The Vancouver Province. August 5, 1932. p. 9.

Bovril. “They Must Have Been Giving Him Bovril.” Advertisement. The Ottawa Citizen. November 13, 1940. p. 5.

Bovril. “When Illness Threatens.” Advertisement. The Montreal Gazette. November 5, 1930, p. 11.

Bovril. “Why Bovril Prevents that Sinking Feeling.” Advertisement. The Montreal Gazette. February 3, 1931, p. 11.

Bovril. “Why Children Need Bovril.” Advertisement. The Vancouver Province. September 25, 1935. p.10.

Bovril. “Why- Children Need Bovril.” Advertisement. Edmonton Journal. October 3, 1935. p. 2.

Bovril. “A woman’s work is never done”. Advertisement. November 3, 1933. The Vancouver Sun. p. 11.

Bovril. “Yes, doctor – Bovril is just what he needed.” Advertisement. The Toronto Globe. January 17, 1933. p. 10.

Copp, T. 1974. The Anatomy of Poverty: The Condition of the Working Class in Montreal 1897-1929. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart.

Featherstone, M. 1982. “The Body in Consumer Culture.” Theory, Culture & Society 1 (2): 18–33.

“Great British Brands: Bovril – Created for the French army and used by Scott and Shackleton, Bovril has a rich past and retains consumer loyalty.” Advertising. (August 1, 2002): 11.

Lears, T.J.J. 1981. No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation American Culture. New York: Pantheon Books.

MacLennan, A.F. 1984. “Charity and Change: The Montreal Council of Social Agencies’ Attempts to Deal with the Depression.” Master thesis, McGill University.

McCuaig, K.E. 1979. “The Campaign Against Tuberculosis in Canada 1900–1950.” Master thesis, McGill University.

Poutanen, M.A., S. Olson, R. Fischler, K. Schwartzman. 2009. “Tuberculosis in Town: Mobility of Patients in Montreal, 1925–1950.” Histoire sociale/Social history 42 (83): 69–106.

Steinitz, L. 2014. “Making Muscular Machines with Nitrogenous Nutrition: Bovril, Plasmon and Cadbury’s Cocoa,” in Food & Material Culture: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2013. ed. Mark McWilliams: 289–303. Devon: Prospect Books.

Tetreault, M. 1983. “Les Maladies de la Misère: Aspects de la Santé Publique a Montréal 1880-1914.” Revue d’histoire de l’amerique française 36: 507–526.

Turner, B.S. 1982. “The Discourse of Diet.” Theory, Culture & Society 1 (1): 23–32.

Williams, R. 1960. “The Magic System.” New Left Review 4: 27-32.

- Due to the parallel development of print technologies and expansion of colonial trade in the 17th century, the earliest food ads featured imported spices and other non-perishable goods, and livestock auctions were frequently promoted in print as early as the 1600s. The imported goods were sometimes unfamiliar to the readers, and the ads had to convince the readers of the benefits of such foods, so even early food ads suggested these foods would support health, strength, and well-being. ↵

- “Great British Brands” 2002. ↵

- Winnipeg Tribune, Montreal Gazette, Vancouver Province, Windsor Star, Calgary Herald, Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, Victoria Times Colonist, Ottawa Citizen, and Globe/Globe & Mail. ↵

- Bovril. "Yes, Doctor – Bovril is just what he needed.” 1933 ↵

- Bovril. “Bovril helped me save my Boy.” 1937. ↵

- Copp 1974; MacLennan 1984; McCuaig 1979; Tetreault 1983. ↵

- Poutanen et al. 2009; Adams et al. 2008. ↵

- Statistics Canada. ↵

- Bovril. “Why Children Need Bovril.” 1935; Bovril. "Why Children Need Bovril.” 1931. ↵

- Bovril. "Bovril stands alone". 1920. ↵

- Bovril. "Realize the difference made by one spoonful of Bovril.” 1931. ↵

- Bovril. "When Illness Threatens." 1930. ↵

- Bovril. British television advertisement featuring Chris Bonington, who climbed Mount Everest. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LH3PHL6vTJw. ↵

- Bovril. British television advertisement featuring Wendy Brook, fastest swimmer to cross the English Channel. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u40ZhrZPOoU ↵

- Williams 1960. ↵

- Bovril. “They Must Have Been Giving Him Bovril." 1940. ↵

- Bovril. “Enjoy the stimulating taste of Bovril nourishing concentrated beef.” 1938. ↵

- Steinitz 2014. ↵

- Bovril. "Keep warmer with Hot Bovril." 1930. ↵

- Bovril. “Prime Beef is tempting, tasty, and nourishing.” 1938. ↵

- Lears 1981. ↵

- Bovril. "Men and Women are Not Machines" 1940; Bovril. "Why Bovril Prevents that Sinking Feeling.” 1931; Bovril. “A woman’s work is never done.” 1933. ↵

- Bovril. “Tempting and Tasty Bovril Sandwiches are so delightfully different.” 1932. ↵

- Kiefer 2021. ↵

- Turner 1982. ↵

- Featherstone 1982. ↵

a type of paid promotional messaging intended to compel consumers to purchase the promoted product or service.

commercial forms of communications that encourage consumption behaviors; includes advertising, public service announcements, political slogans and campaign elements, health promotion, and public relations efforts.

deliberate, day-to-day eating practices, in which the goal is to consume appropriate amounts of food that is deemed ‘healthy’.

a period of history that started with the Wall Street Stock Market Crash known as ‘Black Tuesday’ (on October 29, 1929) and ending when World War II began; a decade marked by conditions creating food shortages, unemployment, and poverty.

the process of state or regional planning and development of facilities, equipment, energy sources, and manufacturing processes that transform raw resources into manufactured products on a large scale, allowing for mass production.

foods considered to be so high in particular nutrients that they disproportionately benefit the eater’s health; generally a term used in marketing; typically not a term used by professional dietitians.

people aged 90 to 99 years old.

an approach to human health that emphasizes individual responsibility for eating well and getting adequate exercise, along with other individual practices that treat the human body as a machine.