Perspective: Agroforestry

Evelyn Nimmo and André E.B. Lacerda

Evelyn Nimmo is a multidisciplinary researcher, professional editor, and translator. She leads CEDErva, a non-governmental organization that supports research and development of traditional agroforestry systems in Southern Brazil. She has a PhD in Historical Archaeology from the University of Reading, a Master’s degree in Archaeology from Simon Fraser University, and a Joint Honours Bachelor of Arts degree in Anthropology and Rhetoric and Professional Writing from the University of Waterloo.

André E.B. Lacerda holds a bachelor degree in Forest Engineering from the Federal University of Paraná, Brazil, with a specialization in Environmental Management and Engineering, a master’s degree in Botany, and a PhD in Geography from the University of Reading. He is a researcher at Embrapa Forestry in the area of forest ecology and genetics. He has experience working in participatory forest management, environmental restoration, agroforestry systems, and population genetics.

Learning Outcomes

After reading and discussing this text, students should be able to:

- Explain the importance of local/Indigenous ecological knowledges and histories in supporting and developing sustainable food systems.

- Describe the impact that conventional industrial food systems have on traditional food cultures and ways of knowing the environment.

- Demonstrate an understanding of how researchers can integrate scientific approaches and traditional knowledge to develop innovative solutions to food systems challenges.

Introduction

Conventional agriculture applies a one-size-fits-all approach to agricultural production and has ignored the particular connection that small-scale farmers have with their land, the crops they produce, and the ecosystems that they rely on. In Brazil, the result has been massive deforestation, rural exodus, extreme impacts of droughts and other weather events, a significant loss of biodiversity, and a loss of the sense of belonging among farmers.

One of the ways that farmers, researchers, and other actors have begun to address these challenges within the current food system is by using the principles of agroecology. Agroecology is an area of scientific research and a set of practices or methods that uses the science of ecology to develop, design, and implement sustainable and environmentally sound agricultural practices. Agroecological approaches also look beyond the environment and agriculture to include social and cultural aspects of food systems. One example is the consideration of people’s connection and history with the land, and their traditional knowledge about native tree and crop species, as important factors in developing agricultural systems.

Traditional and agroecological erva-mate (yerba mate in Spanish) production systems refer to an assemblage of agricultural and agroforestry practices typical of family farming and traditional communities (such as Indigenous peoples, quilombolas, and faxinalenses) in Southern Paraná, Brazil. The dark green leaves of the erva-mate tree (Ilex paraguariensis; see Figure 1) are harvested, roasted, processed, and consumed as a tea, chimarrão (the regional name for mate, see Figure 2), or tererê, is an infusion that is consumed cold. The cultivation, harvesting, and consumption of erva-mate are practices that have deep cultural significance in southern Latin American countries, from Chile to Brazil, and the history of production and consumption of erva-mate dates back thousands of years. These systems originated in the cultural practices of the Guarani Indigenous people, yet they continued to develop over generations through the exchange of knowledge between Indigenous peoples and settler communities.

Erva-mate is a shade-tolerant species; it thrives naturally in the understory of the Araucaria Forest, a forest ecosystem that is part of the Atlantic Forest biodiversity hotspot. Its cultivation and management are based on traditional ecological knowledge and locally developed natural resource management practices. Precisely because of the way in which erva-mate is produced, in native forests and associated with traditional knowledge, it is a unique agroforestry system in Southern Brazil that integrates a variety of food crops and other non-timber forest products, such as native fruits, corn, beans, rice, and vegetables, as well as the raising of pigs, cattle, and poultry.

Since the production of traditional erva-mate is directly linked to forests, the amount of forest cover in regions where it is grown is highly relevant. This is a key point considering that the Atlantic Forest is a biodiversity hotspot, with high levels of diversity and endemism of associated flora and fauna, and that only about 1% of the original primary forest remains, with new or secondary forests covering between 20% and 25% of southern Brazil. The vast deforestation that occurred mainly in the 19th and 20th centuries is a consequence of an intense process of land use changes that continue throughout the country today. But in areas where traditional erva-mate production continues in Southern Paraná State, rates of deforestation have been less severe (see Figure 3).

Despite the important role of traditional erva-mate production systems in local and regional ecosystem services, cultural identities and histories, and agroecological food production, they are under increased pressure to modernize. These pressures come from the industrial food sector and government agricultural outreach and research agencies, which advocate for transitioning to commodity production (i.e., tobacco, soy, and corn), or abandoning traditional agroforestry practices altogether and increasing erva-mate yields through monoculture cultivation and heavy use of inputs, like pesticides, fertilizers, and other agrochemicals.

Nevertheless, farmers continue to use traditional systems for a range of reasons, including the affective relationships many small-scale erva-mate producers have with the forest and a recognition of the importance of maintaining not only the forest environment, but also the knowledge and practices associated with these management systems.

Central-South Paraná State, Southern Brazil

Over the past 30 years, an informal network has developed in Southern Paraná State that has been working together to support the continuation of traditional erva-mate growing systems. They help leverage and optimize these systems, to increase farmer income and autonomy, value the products that they produce, and better understand the benefits they bring culturally, ecologically, and economically. This network is made up of forest engineers, agronomists, historians, anthropologists, technicians, and outreach workers from universities and state and federal agricultural institutions (such as the State University of Ponta Grossa [UEPG], the Rural Development Institute of Paraná [IDR-PR], and Embrapa Forestry). Farmers from across the region who are engaged in agroecological production, activism, and experimentation are also involved in the network, as are other stakeholders, such as the newly created Centre for Education and Development of Traditional Erva-mate (CEDErva). The network includes people who have been working to support traditional agricultural systems for several decades, as well as newer additions, such as researchers from UEPG and CEDErva, who bring different insights and perspectives. In what follows, we focus on the recent work of this network to consider how interdisciplinary and participatory research and outreach are crucial to supporting the development or continuation of food systems, and how such systems can offer strategies to build resilience in the face of a changing climate and the industrial food system.

Research Methods

In Brazil, the majority of research and public policies support the expansion of the industrial agricultural food system, focusing on large-scale production of commodities such as soy and beef. Because of this, traditional and agroecological food knowledges are considered fringe or outdated, and tend to be marginalized in policy and practice. Therefore, evidence-based research is necessary to legitimize traditional knowledge as an important alternative. While there is much discussion concerning agroecology and sustainable food systems around the world, in Southern Brazil, agricultural research and outreach have mostly ignored these food systems, maintaining a focus on conventional, large-scale commodity production such as soy, corn, and tobacco.

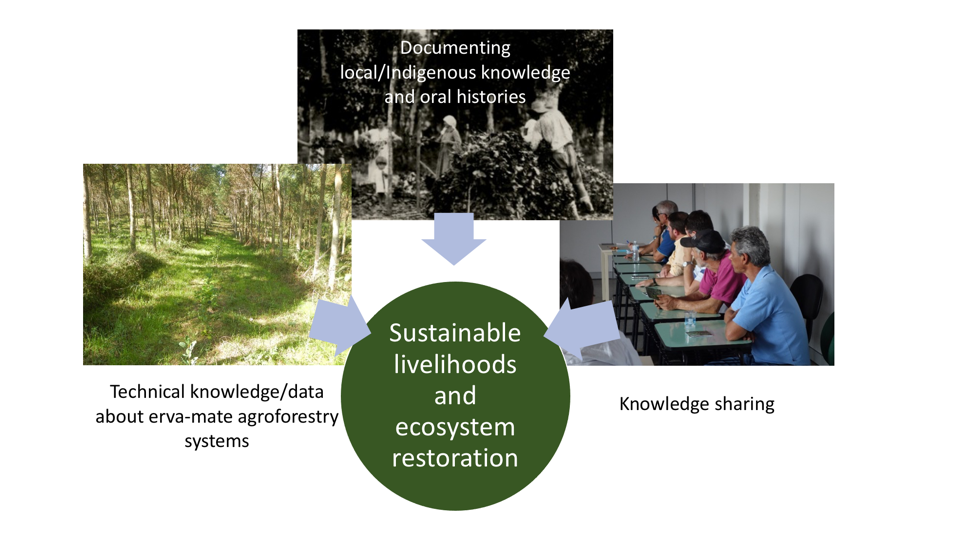

Building on the long-term engagement with communities, farmers, and outreach organizations, researchers in the network are using a wide range of participatory research methods to better understand the historical, social, cultural, and environmental aspects of traditional practices (see Figure 4). Members of the network are conducting workshops, focus group discussions, and field-days in communities to discuss the challenges and possible solutions that farmers experience when practicing agroecological and traditional agroforestry on small-scale farms.

Farmer-to-farmer and farmer-to-researcher knowledge exchanges are key aspects of these workshops and field-days, because they offer a space that values all types of knowledge brought to the discussion. This way of sharing experiences is central to participatory methods, as it ensures that farmers are active participants in the research and that the knowledge created is done collaboratively from the bottom up (rather than imposed on communities from a scientific perspective that is unaware of the realities of life on the farm). The farmers and communities who participate in these events have noted a range of opportunities, including the need to create co-operatives and other solidarity initiatives, a desire to conduct further participatory research to address gaps in knowledge, support for youth in farming, and increasing the participation of women, among others.

Researchers from the History Department at UEPG are also conducting environmental oral history interviews with traditional erva-mate producers to begin to document their knowledge related to the forest. This helps understand the memories, histories, and identities associated with erva-mate and the forest. Such methods are important, as they offer insights into the cultural and historical aspects of agricultural production and environmental protection, showing that the continuation of agroecological erva-mate production is not just an economic decision, but is also tied to how farmers understand their own history and identity as stewards of the forest.

Additionally, the forest engineers and agronomy researchers who are part of the network are testing and replicating traditional production systems, so that these systems can be monitored and measured over time. As a means of addressing some of the technical issues identified by farmers in oral history interviews and workshops, traditional agroforestry systems were replicated in the Embrapa Research Station in Caçador (ERSC), a 1100 hectare experimental area that includes primary and secondary forest and abandoned agricultural fields. Agroforestry systems based on traditional practices were implemented to test a range of strategies identified and developed with farmers, as well as opportunities and techniques for forest restoration. Research that measures the growth of erva-mate and other forest species in experimental areas provides important data on productive cycles. This data includes when to harvest and how much can be produced, as well as the role of forests in promoting ecosystem services, such as biodiversity conservation and the provision of clean water. Research projects also provide the opportunity to improve practices, test innovations developed with farmers in workshops, and develop roadmaps for implementation beyond the experimental area.

A Model for Productive Agroforestry

One of the outcomes of the research in the ERSC was the development of a Productive Agroforestry model that can be used to restore degraded areas. In Brazil, there are strict legal regulations that severely limit the exploitation of forests, such as gathering fuelwood and timber, or any other type of harvesting. Legal Reserves and Areas of Permanent Protection must make up at least 20% of the land cover on small-scale properties in Southern Brazil, and any infraction is met with steep fines. These restrictions have made increasing forest cover across the landscape extremely difficult because some landowners now view forests as worthless and untouchable. Once the forest grows, farmers believe they will no longer be able to use the land or its resources. Innovative productive systems are therefore needed that not only restore diverse and resilient ecosystems, but also follow legal requirements and generate income for the farmer.

Productive Agroforestry models were developed to respond to these needs. They enable the implementation of an agroforestry system using erva-mate and other native tree and crop species that incorporate farmer knowledge, the need for return on investment, and long-term sustainability.

One such model was established in the ERSC in a degraded area that had been cultivated with corn for more than 30 years (see Figure 5). In the first year, pioneer trees species such as bracatinga (Mimosa scabrella) were encouraged to regenerate in rows and were intercropped with beans and soy for interim income. After 12 months, the fast-growing bracatinga trees had established themselves and were thinned out by selective harvesting to sell as fuelwood. Erva-mate was then planted among the tree rows. By the third year, a full forest canopy was created, with erva-mate thriving in the understory. After five years, erva-mate harvesting began, with a range of native species regenerating in the forest environment.

The Strategic Council for Traditional and Agroecological Erva-mate Systems

Another key outcome was the creation of the Strategic Council for Traditional and Agroecological Erva-mate Systems (Observatório dos Sistemas Tradicionais e Agroecologicos de Erva-mate) in 2019. This Strategic Council is made up of representatives from 30 institutions, including state and federal agencies, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), universities, and local chapters of the Family Farmers’ Union, as well as small-scale industries. The aims of this council include supporting research and outreach to ensure the continuation of these systems, while also incentivizing cooperative and solidarity efforts to gain greater autonomy within the production chain. The Strategic Council advocates for traditional systems, working with local governments to develop public policies that support sustainable and agroecological farming practices.

One of the most important developments of this ongoing project has been consolidating the varied individual efforts by a range of different stakeholders through the Strategic Council. Uniting these organizations into one council has helped to focus activities and actions and create a common platform through which to engage farmers, local and regional government, and international organizations. Working together across the network, the Strategic Council has developed a proposal submitted to the Food and Agricultural Agency (FAO) of the United Nations, so that these traditional systems might receive recognition as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS). The GIAHS program recognizes agricultural systems that have evolved as a result of the interaction between humans and their environment, fostering intimate ties between the landscape, local cultures, and agricultural practices. The program supports the continuation of these traditional systems through dynamic conservation and innovation within agrobiodiversity, food security, and landscape management.

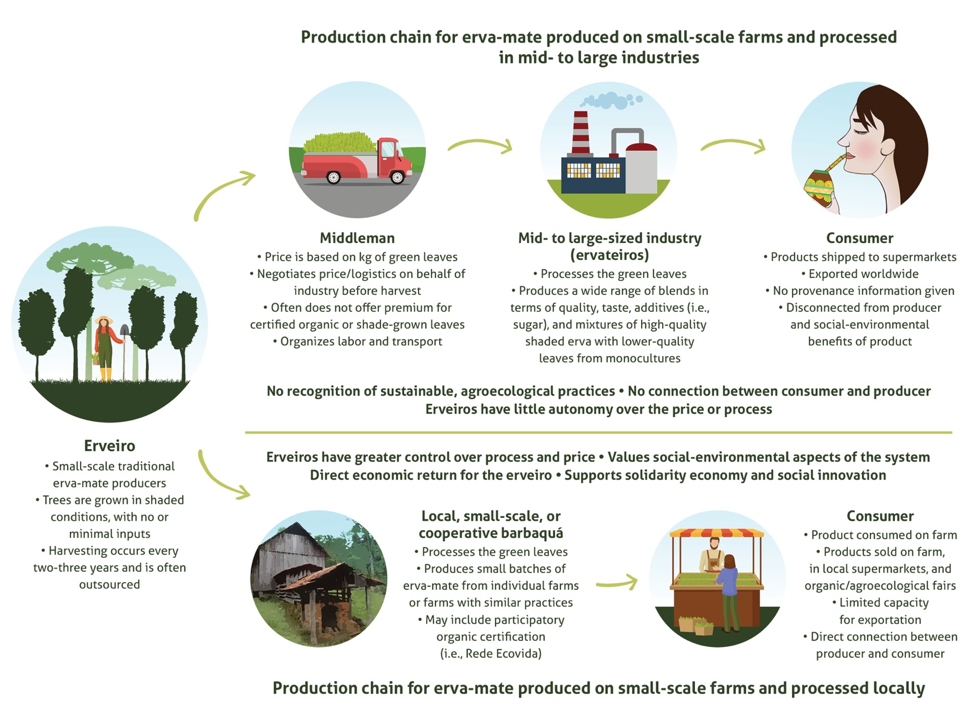

By gaining recognition of traditional erva-mate systems as a GIAHS, only the second in Brazil, the Strategic Council is supporting the consolidation of a community of practice through which farmers can work together to address the many challenges facing the system, including price, supply chain, processing, marketing, and end products (see Figure 6). This community of practice is already working to institute a co-operative for traditional erva-mate and develop a certification system that recognizes the sustainability of the system from ecological, economic, and cultural perspectives. Through these efforts, erva-mate producers are gaining greater autonomy to negotiate prices, diversify their production, and gain recognition for the superior products they produce. This, in turn, brings greater economic stability for farmers.

Perhaps most importantly, the GIAHS program will provide increased recognition of the social, cultural, and ecological value of these systems, which builds community resilience in the face of a range of threats, including rural exodus, a lack of youth engagement, changing climate, and the pressure to modernize and integrate into the industrial food system. In particular, gaining international recognition creates a sense of pride within traditional communities, valuing the knowledge and practices that have developed for generations. As one young farmer pointed out during a workshop to develop the Dynamic Conservation Plan for the GIAHS project, this recognition helps young people envision a future for themselves using these systems, creating possibilities for the continuation of these knowledge and practices.

Conclusion

This research, which involves experts from a variety of scientific disciplines, is documenting and highlighting the role that traditional communities play in forest and biodiversity conservation. Traditional erva-mate producers are not the uneducated, poor, outdated rural folk that many people assume them to be, but are instead stewards of the environment with a deep understanding of the forest. While there remains a distrust between traditional communities and environmental protection agencies, the data being gathered is helping to demonstrate that traditional erva-mate production has been key to providing a range of ecosystem services and benefits for society as a whole, such as protecting the water cycle and maintaining forests.

By creating an evidence base that highlights the important roles that traditional communities play in maintaining agrobiodiversity and forest landscapes, and in continuing traditional agroecological practices, this work is helping to change the relationship these farmers have with environmental and agricultural agencies. The actors in the network and Strategic Council are laying the groundwork to build a better understanding within environmental monitoring agencies of traditional practices, thus addressing the long-standing bias that small-scale farmers cannot be trusted to protect forest resources and strict laws and fines are the only way to deter deforestation.

Through research and advocacy in collaboration with farmers, changes are taking place, with environmental agencies participating in recent events and outreach activities organized as part of this project and becoming active members of the Strategic Council. What is promising is that these agencies are looking to update regulations supported by the data and experiences that such projects are sharing. What can come from advocacy and engagement with these agencies is collaboration with communities to develop public policies that recognize the value of the communities’ work and support their role as stewards of the important environmental and cultural resources the country needs to create resilient and sustainable communities and food systems.

Discussion Questions

- How can traditional ecological knowledge help to diversify food systems? Why might this be important for climate change?

- What are some of the benefits of taking a participatory, bottom-up approach when working with traditional communities?

- What other benefits can agroforestry systems offer, both ecologically and socially?

Additional Resources

Berkes, F., Colding, J., and Folke, C. Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as Adaptive Management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262.

Lacerda, André Eduardo Biscaia, Ana Lúcia Hanisch, and Evelyn Roberta Nimmo. 2020. “Leveraging Traditional Agroforestry Practices to Support Sustainable and Agrobiodiverse Landscapes in Southern Brazil.” Land 9 (6): 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9060176

Nimmo, Evelyn R., and João Francisco M.M. Nogueira. 2019. “Creating Hybrid Scientific Knowledge and Practice: The Jesuit and Guaraní Cultivation of Yerba Mate.” Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 44 (3): 347–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/08263663.2019.1652018

Nimmo, Evelyn Roberta, Alessandra Izabel de Carvalho, Robson Laverdi, and André Eduardo Biscaia Lacerda. 2020. “Oral History and Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Social Innovation and Smallholder Sovereignty: A Case Study of Erva-Mate in Southern Brazil.” Ecology and Society 25 (4): art17. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-11942-250417

Thevathasan, N. V. and A.M. Gordon (2004). “Ecology of tree intercropping systems North temperate region: Experiences from southern Ontario, Canada.” Agroforestry Systems 61: 257–268.

Williams, Brian, and Mark Riley. 2020. “The Challenge of Oral History to Environmental History.” Environment and History 26 (2): 207–31. https://doi.org/10.3197/096734018X15254461646503

A process of migration in which people, often youth, move away from rural areas to cities in search of improved economic opportunities and education, or due to other social and economic factors such as land dispossession.

Multi-functional agricultural production systems that integrate trees (for fuelwood, timber harvesting, or other products) and non-wood forest products (such as medicinal plants, fruits, and nuts) with the cultivation of food crops and sometimes livestock.

A biome or region that has extremely high levels of biodiversity and endemism, meaning that many of the species are only found in that biome. Hotspots are also at high risk of destruction from deforestation and other forms of environmental degradation.

Knowledge, practices, and beliefs that have developed over generations and that relate to the interactions between all living things—including humans (also called local ecological knowledge). The concept often refers to Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing, but can also be applied to settler communities that have developed continual, historical resource-use practices.

A species that is found in a unique and specific geographic location is said to be endemic to that place. Endemic species are more limited than species that are considered indigenous to a place, which means that they can also be found in other geographic locations.

Forests that have reached their most advanced stage of complexity or succession in terms of age and diversity (also known as old-growth or climax forests). Forests tend to go through several stages of dynamic succession, or development, from initial growth of shrubs and pioneer trees to states that are more biodiverse and well developed, finally reaching a final dynamic stage of complex, primary forests. These forests are some of the most dense and biodiverse biomes in the world and are responsible for a vast amount of carbon sequestration worldwide.

Forests in a stage of regrowth after disturbance, due to clear cutting, fire, or extreme weather events like hurricanes.

The wide range of contributions and benefits that ecosystems provide for human well-being, including: supplying food, fuel for cooking, and water; regulating functions of the environment such as pollination and maintaining a stable climate; creating cultural opportunities such as recreation; supporting functions like water cycling and photosynthesis.

the set of emotions and feelings that produce visceral and personal connections with other people, objects, and ideas

A research practice that involves a range of collaborative approaches to ensure that community members and other stakeholders are active participants in the design, implementation, and analysis of research results. Methods can include interviews, focus groups, community mapping, dialogues between communities and researchers, and many others. The goal of participatory research is to ensure that research activities and outcomes are inclusive and relevant to the communities involved, making the active participants in the process of creating and disseminating knowledge, rather than passive objects of academic research.

A discipline that combines methods and concepts from oral history (such as interviews, narratives, and memory) and environmental history (which focuses on the relationship between people and their environments throughout history). It is used to examine the range of perspectives people have on ecosystems, forests, conservation, among many other environmental issues. Environmental oral history focuses on peoples’ perceptions of, and relationships with, their environment, which enables an understanding of the ways people produce meaning from the places they inhabit, and how they perceive and value the natural world around them.

Intercropping is a practice used in agriculture in which two or more crops are grown together in the same field or area. These can be conventional species such as oats intercropped with rye, or they can include tree species—such as coffee trees—planted alongside chili peppers. Intercropping provides benefits such as improving the nutrient availability in the soil and pest management. It also takes advantage of the natural differences in plant growth, for example planting species that require greater levels of shade in the understory of tree crops.

A group of people who share a concern or an interest and come together to pursue common goals through a set of shared methods or processes.