Case: Food in Kyrgyzstan

Christian Kelly Scott and Guangqing Chi

Christian Kelly Scott is a postdoctoral associate in the Department of Geosciences at Mississippi State University. He holds a PhD in Rural Sociology and International Agriculture & Development from Pennsylvania State University. His research focuses on societal issues of hunger and food insecurity. His dissertation focused on the economic, environmental, and social determinants of household food security in the rural southern Kyrgyz highlands.

Guangqing Chi is a professor of rural sociology and demography and director of the Computational and Spatial Analysis Core at Pennsylvania State University. Dr. Chi is an environmental demographer with a focus on socio-environmental systems, aiming to understand the interactions between human populations and built and natural environments, and to identify important assets (social, environmental, infrastructural, institutional) to help vulnerable populations adapt and become resilient to environmental changes.

Learning Outcomes

After reading and discussing this text, students should be able to:

- Examine practices of food gathering, eating, and meaning-making using the principles of political ecology.

- Explain how food, environments, and identities are related.

- Describe the importance of everyday experience to food studies.

Introduction

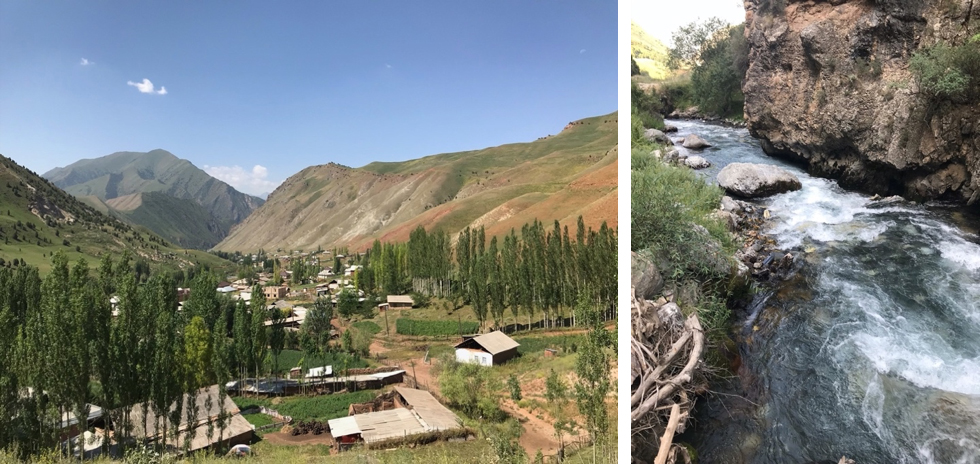

Cascading, poplar-lined rivers, along with glacier-peaked mountaintops and lush, fertile pastures are everyday aspects of rural life in southern Kyrgyzstan. The community members whose experiences are discussed in this text reside in a village that lies in a valley overlooked by steep mountains on both sides. To the north lies a brightly colored slope of red, yellow, and orange sediment and rocks. To the south are dark rock outcroppings with clusters of ancient, stoic, deep-green juniper and spruce trees. Both sides show the telltale markings of landslides in the distant and recent past. The surrounding ecology shapes what each day and night bring for the people in southern Kyrgyzstan. Life in the village and life in the mountain pastures are intimately tied to the passage of seasons. There is a close tie among humans, environment, and food, which lends itself to the application of political ecology theory—the study of environmental themes that are inherently tied to human political, economic, and social factors.

Livelihoods in these rural communities are centered on traditional agropastoral practices—a mixture of sedentary agriculture practiced in mountain valley villages and semi-nomadic livestock management in mountain pastures. Environmental subject making and identities, explained in detail below, are reproduced in the types of food that are prepared, preserved, shared, or traded, and consumed in the villages and pastures. This text outlines the ways in which the theoretical foundations of political ecology are demonstrated in the meaning of food for the people in a rural community. The principles of political ecology are demonstrated in ways that reflect the composite meanings of food in multiple contexts in this area. Drawing on data collected throughout four seasons of the same year in rural southern Kyrgyzstan, our examination of food demonstrates how diets and meals reflect the surrounding mountain environment.

Political Ecology

The theory of political ecology enables the analysis of humans and the environment as innately linked together through interactions among biophysical, cultural, economic, political, and social factors.[1] Five core concepts make up a framework for political ecology: environmental knowledge, environmental subjects and identity, environmental change, environmental governance, and environmental political objects and actors.[2] Environmental subject making and identity means that “people’s behaviors and livelihoods (their actions) within ecologies influence what they think about the environment (their ideas), which in turn influence who they think they are (identities).”[3]

In food studies, political ecology is useful for situating the experience that people have in their food relationships within the spatio-temporal context of their environment. This concept is brought to light here by examining how people perceive food in agropastoral Kyrgyz communities. By applying this framework to the study of food, we were able to focus on ways in which people derive meaning from what they eat, how they eat it, and where it comes from. We reached beyond the surface of merely analyzing interviews and embraced the connections and complexity of political ecology. With this focus in mind, we analyzed interviews of local residents conducted in their homes and yurts (a round mobile dwelling used by nomads), villages, and pastures to shape our understanding of food as a source of identity and practice.

Research Process

We conducted 44 interviews with adults in a rural southern Kyrgyz community. The interviews took place throughout the winter, spring, summer, and fall of 2019, and aimed at understanding seasonal aspects of food security. Interviews were recorded in Kyrgyz and translated into English for analysis. The semi-structured interviews allowed for an open discussion about rural life, food systems, and relationships with the surrounding mountain environment.[4] Transcripts were coded to focus on identifying, describing, and linking themes.[5]

Pastures and livestock

Traditional livelihoods in rural Kyrgyzstan are oriented around agropastoral practices. These include sedentary agriculture produces a small yield of mountain-friendly crops (such as potatoes, which can grow in the harsh conditions with the limited growing season) and seasonal vertical transhumance (i.e., movement from higher pastures in the summer to lower pastures in the winter). The latter takes place with livestock (mostly horses, cattle, and sheep) in mountain pastures. One mother of five highlighted the importance of livestock by saying, “Well, our life revolves [a]round the livestock, each day, repeatedly. That’s the reality in [the] village… That’s the way we live. [We have] no other income apart from that.”

The mountain pastures are therefore key places of environmental interaction. This interaction takes the form of spatial movement when traveling in pasture and staying in yurts and villages, as livestock is grazed, slaughtered, herded, breed, sheared, and milked. The foundation of seasonal diets is derived from livestock and livestock products. These ideals were voiced by one mother as she was baking bread with her daughter: “People love dairy products here in the village. Dairy products are our main diet. People call it aktyk, which means ‘white food.’ The times when cows produce less milk we say, ‘We are having a tough time without white food.’ Today our cows are out in pasture, so we are having tough times. To cope with the shortage of milk, once in a while we go to pasture to bring some milk, ayran, and kymyz [examples of white foods].”

But the adaptive food preparation strategies that households deploy to make it through times of scarcity are also tied to cultural identity and the historical legacy of the community. One father of six said, “You can also preserve jukka [a mixture of yogurt, butter, and flour] for years. This is why we’re called the nomad nation. [Our ancestors] practiced a lot of these preservation methods because it was easy to take [those foods] everywhere.” Movement in pastures and the intergenerational legacy of nomadic movements are tied to the meaning of food preservation and food consumption. In this way, food preservation takes on a meaning not only as a source of resilience to food shortage but also as a celebration of the proud heritage among the Kyrgyz people.

Seasonal diets

The passage of seasons in the mountains of the southern Kyrgyz highlands influences the precise makeup of household diets. Another mother of five articulated this by saying, “Of course, [household diet] changes [seasonally]. During autumn we have high harvest, so we have a lot to eat, and we eat a lot. In February and March our preservations are over, so we have difficulties. Not difficulties actually, [because] we know spring is coming, so we will have food [then].” The local environment changes starkly with the season. Winter is characterized by thick snow cover, and summer is accompanied by lush pastures, so the food security status of households also changes. Diets are closely related to the relationship that the community has with the environment through these changes. In winter, food is in short supply and diets need to change to consume fewer fresh foods.

Community members said that the utilization and availability of foods often coincide with the processes of raising livestock in the mountain pastures. Another mother of five explained, “When the fall comes, our livestock gets fat, times of abundance, everything is ripe. We cook a variety of dishes. In the winter and spring, [consumption of] meat and nutritious [food decreases]… In general, spring is [a time] of scarcity.” Here we see how livestock and pastures relate to the perceived abundance or scarcity of food throughout the year. The reference to fall and summer abundance is in stark contrast to the previous mother’s reference to times of difficulty when there may be an acute shortage of food in winter and spring.

The importance of meat

Food can take on a meaning reflective of the Kyrgyz ethnic identity that links the mountain environment and pastoral movement through explicit statements that community members made about meat: “Meat is the most important ingredient in our meal. It should always be available. A meal without…meat is like a low-calorie food. We can’t live without meat. If we eat food with no meat in it, we can feel a weakness.” With those words, this mother explained how meat is vital to making life possible in the mountains and, without it, survival would be difficult. Meat comes from livestock that are well suited to life in the mountains: sheep, horses, cattle, and goats. The type of meat that was available was also seasonal, depending on whether the livestock were in distant pastures during summer or in village stables during winter.

But meat is about more than just survival—it also links the ethnic identity of the Kyrgyz people to the surrounding mountain environment: “First of all, we consume the Kyrgyz food—meat—as all Kyrgyz people do.” And, when asked about the foods they eat, one young mother of two said, “Mainly we eat boorsok [fried dough], oromo [rolled dough with cube-cut, steamed potatoes], etc. We fry potatoes, meat. You know, Kyrgyz foods. These are our main foods.” To these community members, to be Kyrgyz, at least in these communities in the mountainous rural highlands, is to eat meat.

Nature provides

The final observation that demonstrates the meaning of food as a source of environmental identity among community members is how the respondents articulated their relationship with and utilization of nature as a source of resilience and sustenance. One grandfather of eleven stated, “We, Kyrgyz people, are ancient people. We are resourceful. Even if we do not have flour today, for example, we will find a way to make it work somehow… If we have no imported groceries, we can go to the mountains, hunt mountain deer, and still get by. Or we can set bird traps to hunt for meat.” This grandfather linked their identity and ancestral heritage to the resilience that the environment enables through wild-sourced foods. Another community member discussed the importance of nature in providing nutritious, wild-sourced foods. Likewise, a young father of one son linked natural foods to previous generations and traditional medicines: “Today they also collect from the mountains. There are things to collect, thanks to God. For example, they collect black currant, rosehip, green onions. They save some for winter, they eat some. In the old times, everything depended on the mountains… People eat more things that are natural… There are [also] special herbs for medical purposes.”

Discussion

Our observations and interviews show how the idea of environmental subject making and identity is linked to the meaning of food in a real-world setting. The livelihoods and personal identities of these Kyrgyz community members are shaped by their surrounding mountain environment. One community member, a father of four, perhaps said it best and most simply: “Here everything is connected to…nature. We eat clean. We have clean air.” The fundamental implication of this research is that the meaning of food, as seen through a political ecology lens of environmental subject making and identity, is not an abstract ideal. Community members stated clearly that food took on a meaning that reflected how the surrounding ecology shaped their lives and their own environmental identities. It also speaks to the importance of incorporating everyday experience into food studies, especially when examining something as complicated as the meaning of food and the role of food in shaping identities.

Conclusion

This study provides a practical example of how food is conceptualized in a unique environmental and sociocultural context. The observations of pastures and livestock, seasonal diets, the importance of meat, and foraging from the landscape demonstrate the interconnected relationship between food, identity, and the environment. Food may not mean the same thing to everyone in the same community, let alone to different populations in completely different geographic contexts. It is therefore helpful to bring critical perspectives to the forefront, particularly for research conducted in places that are under-represented in scientific studies, such as Central Asian countries and, specifically, communities in rural Kyrgyzstan.[6]

Discussion questions

- What does food mean to the members of communities in rural Kyrgyzstan? How do the meanings of food, the environment, and personal identity relate to each other in this context?

- Drawing on your own experience(s), identify a food that is connected to both identity and the environment. How do the meaning of food, the environment, and personal identity relate to each other in this context? How does this relationship differ from example from rural Kyrgyzstan described in the chapter above?

- How does each of the four observations—pastures and livestock, seasonal diets, the importance of meat, and nature provisioning—exemplify the connection of food to everyday life in the Kyrgyz highlands? What are some potential observations about everyday life and food that shape your identity?

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the J. William Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board, the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and Multistate Research Project #PEN04623 (Accession #1013257), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Award #NNX15AP81G), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Award # P2C HD041025), Pennsylvania State University Libraries (Whiting Indigenous Knowledge Student Research Award), and the Social Science Research Institute, the Department of Agricultural Economics, Sociology, and Education (M.E. John Memorial Endowment Graduate Student Thesis/Dissertation Research Award), the College of Agricultural Science’s Office for Research and Graduate Education, the Office of International Programs, and the Institutes for Energy and the Environment of the Pennsylvania State University. The findings and conclusions do not necessarily reflect the view of the funding agencies.

References

Bridge, G., J. McCarthy, and T. Perreault. 2015. “Editors’ Introduction.” In The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology, edited by Tom Perreault, Gavin Bridge, and James McCarthy. New York, NY: Routledge: 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.11.004

Ellis, J., and R. Lee. 2005. “Collapse of the Kazakstan Livestock Sector.” In Prospects for Pastoralism in Kazakstan and Turkmenistan: From State Farms to Private Flocks, edited by C. Kerven. London, UK: Routledge Curzon: 52–76.

Neely, A.H. 2015. “Internal Ecologies and the Limits of Local Biologies: A Political Ecology of Tuberculosis in the Time of AIDS.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 105 (4): 791–805.

Robbins, P. 2012. Political Ecology: A Critical Introduction. 2nd Ed.. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Robie, T. S., Tyler, V. Q., Al-Omair, A., Ahmed, S. E. H. E. T., Schaffer, T., Imanalieva, C., … Harvey, P. 2011. Situational Analysis Report: Improving economic outcomes by expanding nutrition programming in the Kyrgyz Republic. Washington, DC: World Bank/UNICEF.

Saldana, J. 2016. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEST.2002.1041893.

Scott, C.K. 2021. “The Pasture, the Village, and the People: Food Security Endowments and Abatements in the Southern Kyrgyz Highlands.” Dissertation. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University.

UNICEF. 2015. “Situation Analysis of Children in the Kyrgyz Republic.”

the relationships of humans and their environments, manifested through interactions between biophysical, cultural, economic, political, and social factors.

inclusive of both space and time.