Case: Japanese Food Identity

Maya Hey

Learning Outcomes

After reading and discussing this text, students should be able to:

- Name an example of a food identity and explain how one comes to embody it.

- Compare the internal and external processes of identifying with a food practice.

- Consider and critique at least one aspect of the (sometimes problematic) relationship between race/ethnicity/culture and authenticity, with regards to food.

Introduction

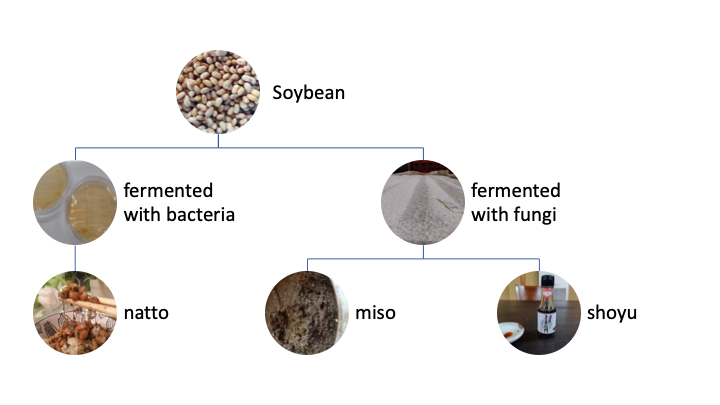

Natto is a fermented food made with soybeans. Originating in Japan, it is often served as a topping to rice. Natto is one of the many ways that Japanese food culture preserves soybeans—an important source of protein—through the process of fermentation. Historically, fermenting soybeans ensured that people had access to vital nutrients long after the bean was harvested, producing such products as miso or shoyu (better known as soy sauce in the West). Unlike miso and shoyu, however, natto takes a shorter time to ferment (two to four days versus several months). Part of this difference is due to the fact that natto is fermented with a bacterial species called Bacillus subtilis, whereas the other soy-based ferments tend to use fungi (of the Aspergillus and Rhizopus species). Originally, the bacteria that transform natto came from dried rice stalks when farmers would try to preserve the bean, although nowadays the commonplace nature of natto in Japan means that most of it is mass produced in styrofoam packets.

You might be thinking at this point, why is it that miso and shoyu are fairly internationalized while natto remains less known? Natto is unique in its texture and is often regarded with a mixture of fascination and disgust. On the one hand, natto is hailed as a superfood and probiotic due to its health benefits, helping to combat conditions such as neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s), cardiovascular diseases (e.g., hypertension, stroke), and intestinal distress (e.g., colitis, irritable bowel syndrome). On the other hand, natto looks stringy and has a slippery feel on the tongue, which tends to be a rare experience for eaters (aside from eating vegetables like okra and molokhia). As with other novel experiences, what remains unknown or unfamiliar to the eater may simply be written off as ‘weird’ or ‘suspect’.

What is peculiar about natto is that some folks in Japan do not enjoy its flavor, either. That is, natto is not universally loved by the Japanese people, yet it can be used as one of many yardsticks to measure someone’s Japanese identity. Like many food identities, the repeated acts of consuming a food can bolster a person’s sense of self: I am who I am because I/we eat this food. Or, on a collective scale: We are the people who eat these foods; they are the people who eat those foods. What we eat (or don’t eat) can define who we are, but more than that, the practices we regularly perform with those foods can inform our food identities.

Of course, this is not unique to Japan or to natto. Many foods can define individual values and collective belief systems, whether in vegan diets, Kosher dietary laws, or national dishes. Identities, especially food identities, are not fixed because they are subject to contextual differences that change the ways that food identities are practiced. Food practices, in all places, with all sorts of foods, can both create and undermine identity.

As a person of Japanese heritage, I recognize that eating is part of a whole host of identity performances informing who I am. Of all of the things I eat that connote my Japanese-ness, I am particularly drawn to how natto leverages identity: to what extent does natto connote Japanese-ness as a food or even connote Japanese-ness in food identities? The answers are not straightforward, partly because Japanese-ness is negotiated by a mixture of forces happening at the same time, some culturally rooted, some socially situated, others purely happenstance. I focus on natto because, as a ferment, it emerged out of necessity (i.e., food security), but as a contemporary food choice—and one that isn’t celebrated universally—it is an anomaly worth exploring, to analyze the socio-cultural dynamics that it brings out. These practices include choosing natto (over other foods), preparing it, and consuming it.

Grounded Observation

In this text, I examine the ways in which consuming foods like natto can inform one’s sense of self or subjectivity. Rather than generalize the current state of natto consumption, my approach to this chapter is based on a sample of one, myself. To accomplish this, I use some of the tools used in autoethnography because these methods allow me to study how and why natto gathers meaning on personal and societal scales. By keeping my observations grounded in the specific details that make up my lived experience, I can make claims without committing the error of speaking on behalf of others, or of reducing “natto” or “Japanese-ness” to a set of criteria. Importantly, a subjective approach sees knowledge as always being partial—both in terms of being part of a whole as well as being partial to (or inherently biased towards) something. In this way, my observations are seen as a truth, instead of the universal truth. As many feminist thinkers argue, accounting for this partiality is critical to demonstrate how subjective knowledge is not lesser than objective knowledge, but is rather an attempt to convey (one type of) reality. I also draw on interviews and fieldwork during a multi-sited ethnography of fermented foods in Japan.

The Slippery Materiality of Natto

Like many other food cultures, Japan boasts a legacy of fermented foods (besides the aforementioned miso, shoyu, and natto, there are a variety of pickles, sakes, and garums). Thus, fermentation is part of the cultural identity of Japan, making ferments like natto a unique opportunity to study how its preparation and consumption give meaning to the people who handle them.

Think about the fermented foods you might encounter: bread, kimchi, sauerkraut, wine, cheese, and yogurt. Most of these are acidic—as in sourdough bread, sauerkraut, fermented dairy from soured milk—because of the acid-producing bacteria that ferment them. The acid adds complexity in taste while also helping to preserve the fermented ingredient (e.g., most cheeses can last longer than a glass of milk). This is where natto differs, because it undergoes an alkaline fermentation process. Alkaline processes are the opposite of acidic ones, and many proteins and seeds in Asia and Africa are preserved in this manner (e.g., fresh poultry eggs are fermented into pidan, or “century eggs”). In alkaline fermentation, proteins are broken down into units of amino acids. And while this often leads to intense, unctuous flavors (umami), when left to ferment for too long, the broken chain of amino acids produce ammonia and can give off a putrid smell.

So even before one handles natto, the scent of it is already wafting through the air, usually in the form of a bleach-like or pungent odor (similar to old bloomy-rind cheeses, like Brie or Camembert). Some people mitigate the smell by adding other flavors to natto including alliums (e.g., green onions), seasonings (e.g., more shoyu), or other vegetables and herbs (e.g., radish, mitsuba). Others avoid natto entirely.

Another material reality of natto is its stringy texture, which some people characterize as sticky, gooey, and slimy. This stringiness is also an effect of the fermentation process, in which bacteria breakdown the soybeans to produce thin wisps of polyglutamic acid that have the weight and feel of a single strand of cotton candy or a spider’s web. (It is in these strings that the bioactive compound, nattokinase, is located, which is known to improve one’s heart health.) In fact, the act of stirring vigorously encourages the polyglutamic acid to come to room temperature and release glutamates, which help produce the sensation of umami or savory tastes in the human tongue.

Stirring the natto makes it easier to eat as well. Natto often comes in a square styrofoam container, similar in size to a deck of cards. The top opens up like a scanner lid, and on top of the natto beans lies a plastic liner with two sauce packets (one shoyu-based, one mustard). A common ritual for natto eaters like me is to carefully peel back the plastic liner so as not to take any of the beans with it. After adding one or both of the sauce packets, I grab a set of chopsticks in one hand, and with a firm grip, whir my hands around in a circle so that the natto strings start to wrap around itself. Since individual beans might be difficult to grasp with chopsticks, the stirring encourages the natto beans to clump together, making it easier to eat in bite-size portions.

Can You Stomach it? Gauging Authenticity and Foreignness

The mucilaginous texture of natto—and one’s ability to tolerate or enjoy it—grants a person membership inside Japanese culture, or so the belief goes, because it is considered to have a taste and texture that only a Japanese individual could enjoy. Here, I turn to my own experiences of eating natto as a Japanese hafu, a Japanese term used to describe half-Japanese people.

When I was growing up in Japan, I was often asked if I preferred bread or rice for breakfast, which, even in my young age, I knew was an indirect question about whether I identified more as Japanese (native) or Western (foreigner). In the context of late 20th-century modernization, bread at breakfast came to symbolize how Japan engaged with global food practices, and the rest of the Western world. When I would indicate my preference for rice, I would often be met with the follow-up question regarding my thoughts on natto—that is, whether or not I could stomach it. Because I had been eating it since my childhood, I considered it an ordinary rice topping, analogous to butter on bread. The reaction to my response was always one of approval and assurance, as if I had passed an unspoken test.

As I would eat the natto, I would twirl my chopsticks after each bite so as to cut off the stringiness of the natto beans. Seeing this, other Japanese would see this as a sign that I was in-the-know: I knew how to handle natto. To this Japanese audience, eating natto validated my Japanese identity.

How (Japanese) authenticity gets monitored and enforced can have consequences that range from solidarity to sinister gatekeeping, and much of it has to do with how we imagine degrees of cultural or ethnic identity. That I am part Japanese means that my identity fluctuates depending on the context. In Japan, I am often seen for my half-ness, which, by definition, means that I could never be whole or fully Japanese, so I am rendered an outsider—at least until practices like natto-eating grant me an exception. This follows a nationalistic rhetoric of always being ‘not enough’ to be let into a dominant culture, something that many mixed-race and multi-ethnic people experience. In a Western context, however, I am often seen only for my Japanese identity, and called upon to speak on behalf of “my people” as if I were their representative (e.g., “tell us why your people eat that slimy stuff”). This manifests into tokenism, exoticism, or being ‘good enough’ to conveniently use a person’s identity as the whole, usually for questionable purposes like racial profiling or commercial marketing. Context certainly matters, but perhaps more important than what I am in each setting is the fact that I consider my identity to be fluid, depending on place-based context and, to the extent that these places allow, the values that I practice.

These practices include what I eat and how. I enjoy natto both as a nostalgic taste and as a health food, but it is part of a greater constellation of other practices: how I slurp my noodles, how I bring a teacup to my lips, how I begin and end each meal with gratitude—some of which can be coded as ‘Japanese’ practices, some not. Alongside these food practices are others that one can also embody: language, dress, manners, and more. I choose to continue this range of practices because they ground me in a past that I share with my relatives and ancestors. By making a ritual out of these practices, I can continue to uphold these values as long as I carry these practices in my body and pass them on to generations after me.

Conclusion: How Embodiment Informs Food Identities

How we embody a food can define us in both literal and figurative ways. Embodiment refers to the process of incorporating things into one’s body, including foods and their practices. To embody a food means to ingest its molecules, which then become the building blocks of our physical being (e.g., soy proteins, nattokinase). Yet we embody the practices that accompany the food as well, especially as they help form a cultural identity with repetition (e.g., twirling chopsticks to cut off the stringiness of natto). For natto in particular, the materiality requires a different set practices compared to other fermented soybeans like miso and shoyu, slotting natto and its practices as a distinct food and ritual in Japan.

How we embody foods and their practices can lead to a sense of belonging to (or being foreign to) a given food culture. The sense of self that comes with eating natto is sometimes internally defined (e.g., I eat this because it reminds me of my family) or externally imposed (e.g., I won’t eat this because people will think I am different). Given the fact that other food cultures also have alkaline ferments (e.g., cheonggukjang in Korea, thua nao in Thailand, dawa dawa in Nigeria), I wonder to what extent these places also use the embodiment of these foods as part of reinforcing a racial, ethnic, or national identity.

Eating natto may not inherently make one Japanese, not in the sense that it can confer citizenship or fulfill a checklist to becoming Japanese. Instead, natto distinguishes itself as a ferment (even in Japan) such that one’s ability to prepare it, eat it, and enjoy it reinforces its singularity—a uniqueness that can be selectively called upon to include and exclude those who handle it. So whether natto is or isn’t a Japanese food is secondary to the fact that some people use it to make sense of Japanese-ness in an increasingly globalized world.

At the same time, ‘Japanese-ness’ cannot be flattened into one experience—not by natto or any other foodstuff we call Japanese. While I am mostly writing from my own experience in Japan, it is also worth noting how Japanese-American, Japanese-Canadian, and Japanese-Brazilians cannot be collapsed into a singular Japanese category because they neither share the same histories nor were subject to the same political forces around migration, internment, and land ownership. A similar caution goes for nuancing the phrase “of Japanese descent,” in that people who identify as nisei, sansei, and yonsei (terms for second-, third-, and fourth-generation, respectively) experience Japanese-ness differently, usually along the lines of language affordances, cultural adaptations, or lost connections from uprooted homes. Again, identities are not fixed. It is from repeating practices that meaningful identities can form and inform who we are.

Repeatedly practicing the nuanced rituals associated with natto thus make up my layered process of identifying with Japanese food culture. To think that I am who I am because I eat this food works only if we dig deeper into how the Self comes to understand itself. Philosophers call this subjectivity, and it is perpetually shaped and reshaped by how we engage with the world around us as we try to make sense of it. This is why philosophers often write of subjectivity as being produced, because it is an active process of the Self becoming an individual.

To embody something, be it food or an identity, connects the physical with the figurative. Eating ferments like natto is just as much a social and cultural way of being as it is a political encapsulation of embodied difference. Natto can be a slimy food known by its stench and stringiness that prejudice can write off as being unsophisticated or gross, while at the same time, it can be a nostalgic or culture-specific food that eaters celebrate as a kind of belonging. What matters is that these processes are always and already ongoing, affected by and affecting how we make sense of the world around us. And, even as we do so, we are making sense of who we are as we exist in this world.

Discussion Questions

- How does embodying certain foods define one’s identity? Name and explain a few examples of the food you embody and the meaning it provides to your identity.

- Consider the difference between self-identification and external labels in food identity. Who has the ability to define themself? Who decides what is a food identity and how is it enforced?

- Many foods and identities are essentialized (reduced to a single aspect). What makes this a problematic way of thinking? What would be a more respectful approach to understanding differences in foods/identities?

- This text relies on aspects of storytelling to present subjective experience. What is the role of personal narrative as the basis for how we come to know what we know?

Additional Resources

Fischler, C. 1988. “Food, Self, and Identity.” Social Science Information 27 (2). https://doi.org/10.1177/053901888027002005

Heldke, L. 2003. Exotic Appetites: Ruminations of a Food Adventurer. New York: Routledge.

Ikebuchi, S., & Ketchell, T. 2020. “It is food that calls us home: A multigenerational auto-ethnography of Japanese Canadian food and culture.” BC Studies, (207), 11–33.

a process in which food matter (and sometimes meaning) is transformed through the metabolism of microbial life (e.g., milk into cheese, grapes into wine).

the result of the way people constitute themselves by following a set of nutritional, cultural, symbolic, collective, and/or ethical values.

a qualitative research method that analyzes personal experience and sense-making through reflection; autoethnography differs from autobiography by taking a wider framework are the site of examination, i.e., one’s own experience.

the process of incorporating physical or abstract things into one’s body, such as food, race, or knowledge—so that they become part of one’s body.

the ways in which knowledge and selfhood relate to an individual; related to positionality and experience; often understood as ‘bias’ or the counterpoint of objectivity; see also human subjectivity.