Perspective: Food Insecurity

Mary Anne Martin and Michael Classens

Michael Classens is a White settler man and Assistant Professor in the School of the Environment at University of Toronto. He is broadly interested in areas of social and environmental justice, with an emphasis on these dynamics within food systems. As a teacher, researcher, learner, and activist, he is committed to connecting theory with practice, and scholarship with socio-ecological change. Michael lives in Toronto with his partner, three kids, and dog named Sue.

Mary Anne Martin is a White settler woman and adjunct faculty member in the Master of Arts in Sustainable Studies program at Trent University. Her interests include household food insecurity, the impact of community-based food initiatives, and intersections between gender and food systems. She actively participates in food policy initiatives and is dedicated to fostering social change through campus-community collaborations.

Learning Outcomes

After reading and discussing this text, students should be able to:

- Describe the systemic dynamics that contribute to food (in)security

- Be able to express the limits of food charity

- Interpret new paradigms that can reframe food insecurity and support its solutions

Introduction

The global COVID pandemic has had far-reaching food systems implications, including for those experiencing food insecurity and for food justice organizations, advocates, and activists. Community-engaged scholars witnessed first-hand how food justice and allied organizations shifted the focus of their work as COVID descended. In a moment of acute and cascading crisis, many organizations returned (if perhaps temporarily) to a charitable food bank model. This case, looking at an example from Ontario, Canada, provides reflections on a number of themes that emerged in the intervening months related to food insecurity, food systems change, and broader issues of social change.

Setting the table

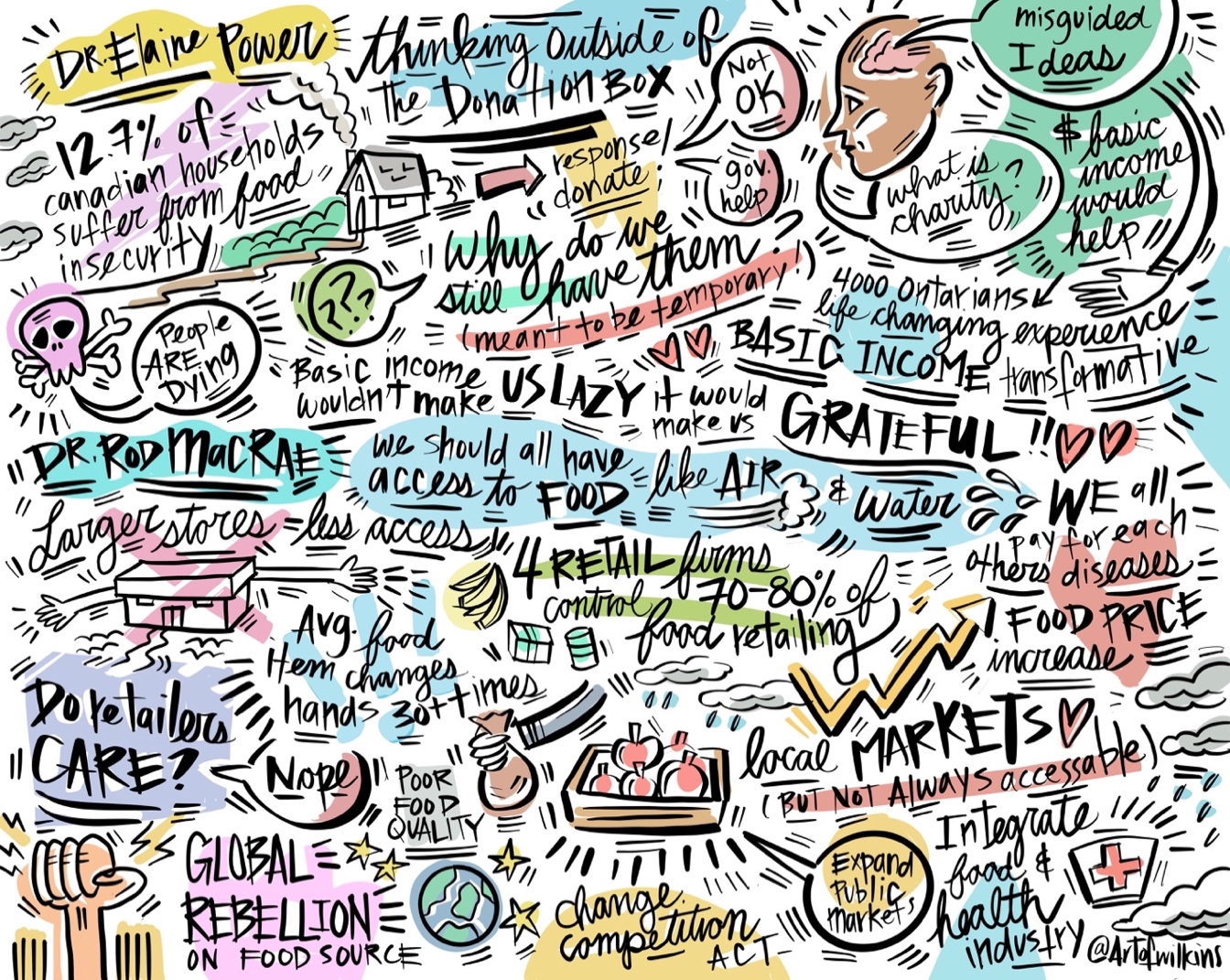

How we understand the problems associated with our food systems is a function, in part, of how we conceive of our food systems in the first place. For interdisciplinary food scholars and activists, understanding food systems means being attentive to a wide range of issues, including “historically specific webs of social relations, processes, structures, and institutional arrangements that cover human interaction with nature and with other humans involving the production, distribution, preparation, consumption, and disposal of food.”[1] What this means in practice isn’t always so clear, however. Nonetheless, thinking through food insecurity, and responses to it, can help provide some clarity and demonstrate why the way we think about food systems matters. For an illustration capturing some of the complexity of these dynamics, see Figure 1 below.

By any measure, food insecurity is a crisis in Canada, and around the world, and it has worsened during the pandemic. The United Nations World Food Programme estimates that there are nearly 700 million food insecure people worldwide, 270 million of whom experience crisis levels of hunger, meaning that they face severe calorie deficiencies and are at high risk of mortality.[2] In more stark terms, the organization estimates that between 6,000 and 12,000 people may be dying of hunger every day.[3] In Canada, about 4.4 million people were living with food insecurity before the global pandemic.[4] By May of 2020, just a few months into the pandemic, food insecurity had risen by 39%.[5]

It is important to keep in mind that these alarming food insecurity rates are unequally distributed across the population, so some demographic groups are much more likely to experience food insecurity than others. For example, a study conducted in Toronto found that Black households are about three-and-a-half times more likely to be food insecure than White households.[6] Indigenous populations throughout the territory known as Canada experience rates of food insecurity from as high as 33% off reserve[7] to 100% on reserve.[8] Among all income brackets, rates of food insecurity are highest for households in the lowest income bracket, and the prevalence of food insecurity declines as household income increases.[9] These numbers (and others) demonstrate that food insecurity isn’t just a food issue, narrowly conceived. Food access is structured within unequal socio-economic, cultural, and ecological systems. In other words, food insecurity is an issue of equity and justice.

One of the main ways we have attempted to address food insecurity in Canada is through food banks. While they may seem like timeless institutions, Canada’s first food bank opened in Edmonton in 1981 to provide temporary measures to support people struggling within the compounding context of high rates of inflation, recession, and scaled-back federal unemployment and provincial social supports.[10] These interventions were always intended to be short-term, stop-gap measures, and yet, by the mid-1980s, there were over 75 food banks across Canada.[11] This was just the beginning of the normalization and institutionalization of the charitable food banking model in Canada—Food Banks Canada reports that there are now more than 3000 food banks and frontline food-serving agencies in their network.[12] The problem is, there are far more food insecure people in Canada now than ever before. So, if the point of food banks is to provide food to those in need of it, they aren’t succeeding even on their own terms. In fact, research shows that only about one in five food insecure people even use food banks.[13]

In contrast to food banks, many organizations can be considered food justice organizations. These organizations don’t understand food insecurity as simply the absence of food, but rather they conceive of food insecurity as a result of broader, inequitable structures resulting from colonialism, White supremacy, misogyny, and unfettered capitalism. Consequently, they also frame food insecurity as more than simply a food issue. As a result of looking at the entire food system through interdisciplinary and equity lenses, many food justice organizations understand the root causes of food insecurity as comprising intersecting social, political, and ecological inequities, and therefore propose solutions beyond food banks.

FoodShare Toronto, a leading food justice organization in Toronto, Ontario, was founded in 1985. It was originally established as a temporary initiative to coordinate among the City of Toronto’s 45 front line emergency food service agencies. Very quickly, the organization understood that broader systems change was required to address the systemic and root causes of hunger. Today, FoodShare is dedicated to pursuing food justice in ways that centre the experience of those most impacted by poverty and food insecurity—Black, Indigenous, People of Colour and People with Disabilities through a variety of programs and initiatives that go far beyond the food bank model.

So, for example, rather than simply providing low-quality, highly processed food to those in need, some food justice organizations offer weekly fresh-produce box programs. Some support the establishment of farmers’ markets in low-income, marginalized, and racialized communities (communities that typically don’t have access to farmers’ markets). In some cases, these organizations buy directly from local growers, in an attempt to address food insecurity while also supporting local, small-scale growers—attending to the struggles of both marginalized eaters and growers.

Beyond providing food for those who need it, some food justice activists, organizations and networks also agitate for policy change. As an example, there have recently been various efforts by a diverse network of food justice and other organizations to compel the federal government to institute a basic income (BI) in Canada. This means that all Canadians would be provided with a sufficient and guaranteed income to meet their basic needs, including food. Research shows that when people have a reliable and sufficient income, rates of food insecurity are significantly reduced.[14]

Other research points to the political economy of our food system, noting that food is in fact a human right, and that Canada is legally bound by international agreements to fulfill the right to food.[15] In Canada just four companies—Loblaws, Metro, Sobeys, and Walmart—control upwards of 80% of the retail market.[16] And these companies prefer establishing larger stores typically in higher-income areas, resulting in an unequal distribution of food access across Canada. Food, many advocates argue, is too important to be treated as a commodity governed by a retail oligopoly.

When the impact of the COVID pandemic began to be felt across Canada, and rates of food insecurity began to spike, we saw many food justice organizations—at least temporarily—adopt a food charity/food bank model. In part, this reflects the efforts of food justice organizations to respond to the increasing intensity of the food insecurity crisis during the pandemic in whatever ways they could. However, this response was also the result of the federal government nudging organizations in the food bank direction. By December 2021, the federal government made $330 million available through the Emergency Food Security Fund. These funds were disbursed through a handful of national and regional emergency food and food justice agencies to smaller, front-line serving organizations. The money was earmarked for the purchase of emergency food provisions, personal protective equipment, and to hire additional workers.[17] In other words, the Canadian federal government conscripted food banks as well as food justice and community development organizations into its efforts to address dramatically increasing rates of food insecurity across the country through charity emergency food provisioning.

Solidarity, not Charity

The first six months of the pandemic were profoundly challenging for many food justice organizations as they adjusted to increased demand for basic food-provisioning services, a reduced volunteer base, emotionally exhausted staff, intense uncertainty, and increasingly marginalized community members. While these challenges persist, many organizations have recalibrated within this difficult context and, in ongoing recognition of the need for food justice, are redoubling their efforts to realize broader structural social change. FoodShare, a leading food justice organization in Toronto, for example, has recently underscored their commitment to food justice, democratic control, and political mobilization as we transition out of the global pandemic.[18]

The COVID pandemic—and the spectre of new, different pandemics resulting from our corporatized and globalized food system—makes the words of feminist philosopher Val Plumwood truer now than ever before, “If our species does not survive….it will probably be due to our failure…to work out new ways to live with the earth, to repower ourselves… We will go onwards in a different mode of humanity, or not at all.”[19] One way to reframe this sentiment within the context of food insecurity is to move beyond thinking about how to end food insecurity, to thinking about how we can create a world within which food insecurity is unthinkable.

As dissatisfying as it may be, there are no clear blueprints to direct us on how to do this. However, there are paradigms and ways of thinking that can inform the development of a comprehensive and integrated plan to transition toward more just and equitable food systems. The feminist economists J.K. Gibson-Graham[20] illuminate how ways of knowing and being in the world are already informing how we can move beyond the need for charity. They see hope in reciprocal relationships, mutual support, care work, and myriad other everyday occurrences that exist outside of the formal capitalist economy. In this, they see the beginnings of a new economic ethic for the Anthropocene—a way of reclaiming the economy as a site of equitable decision making, not simply the accumulation of profit.

The global peasant movement, La Via Campesina, similarly understands food systems as entanglements of human-nature relationships through which to advance equity and justice, a perspective that contrasts markedly with the dominant capitalist food system within which food is treated as a simple commodity. La Via Campesina advances food sovereignty and agroecology, food systems paradigms that promote equity, democratic control, and empowerment of traditionally marginalized groups of people. In various places around the world, these approaches espoused by La Via Campesina have demonstrably resulted in better overall nutrition and enhanced food security.[21]

Another paradigm that can help broaden our political imagination is the notion of mutual aid. This perspective contrasts explicitly with the charitable model by weaving ways of supporting each other into the very fabric of everyday life. It should also be noted that in contrast to some of the approaches summarized above, mutual aid assumes that it is unlikely that the state will ever substantively support food justice. However, the significant resources and policy levers of the state are still necessary for effecting change on a profound and universal basis. As the Big Door Brigade puts it, “Mutual aid is when people get together to meet each other’s basic survival needs with a shared understanding that the systems we live under are not going to meet our needs.”[22] The movement is gaining traction, and recently the United States Congresswoman Alexandrian Ocasio-Cortez collaborated on the development of a “how to” mutual aid strategy resource.[23] The trans-rights activist and lawyer, Dean Spade, argues that moving from charity to solidarity through mutual aid strategies “will be the most effective way to support vulnerable populations to survive, mobilize significant resistance, and build the infrastructure we need for the coming disasters.”[24]

(Re)setting the table

That the negative consequences of the global pandemic have been so disproportionately shouldered by those who are already struggling underscores the fundamental inequities in our world. In Canada, our initial response to deepening food insecurity was to double down on a 40-year-old food charity model that we already knew was ineffective. However, this acute crisis has also inspired many food justice organizations, activists, and scholars to intensify their commitment to food justice, and to imagine new ways of organizing our relationships with each other and nature in ways that make inequity unthinkable.

Discussion Questions

- Why might one’s social location have an impact on their level of food (in)security?

- What other food issues might be reframed by looking at them through interdisciplinary and equity lenses?

- How can we reframe our relationship with food in our everyday lives? What are the limits of individual actions on those relationships?

Exercise

Find and compare websites of a food bank and a food justice organization in your area. How does each frame food? What activities does each organization do? What differences do you notice?

Additional Resources

References

Agriculture and Agri-food Canada. 2021. “Emergency Food Security Fund.”

Big Door Brigade. n.d. “What is Mutual Aid?”

Food Banks Canada. 2020. “Relieving and Preventing Hunger in Canada.”

Food Secure Canada. 2012. “The Right to Food in Canada.”

FoodShare. n.d. “FoodShare’s Locally-Rooted Food Justice Approach to COVID-19 Response.”

Gibson-Graham, J.K. 2006. A Postcapitalist Politics. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Gibson-Graham, J.K. 1996. The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Health Canada. 2004. “Canadian Community Health Survey, Cycle 2.2, Nutrition (2004). Income-Related Household Food Security in Canada.”

Koç, M., J. Sumner, and A. Winson. Critical Perspectives in Food Studies. Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press.

Minister of Health, Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion, Health Products and Food Branch, Health Canada, Ottawa, Canada. 2006.

MacRae, R. 2021. “Equitable Access to the Food Distribution System.”

Ogle, B., H.T.A. Dao, M. Generose, and B.L. Hamnbraeus. 2012. “Micronutrient Composition and Nutritional Importance of Gathered Vegetables in Vietnam.” International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 52 (6): 485–99.

Plumwood, V. A review of Deborah Bird Rose’s Reports from a Wild Country: Ethics of Decolonization. Australian Humanities Review 42 (2007): 1–4.

Riches, G. 1986. Food Banks and the Welfare Crisis. Ottawa: Canadian Council on Social Development.

Roos, N., M.M. Islam, and S.H. Thilsted. 2003. “Small Indigenous Fish Species in Bangladesh Contribution to Vitamin A, Calcium and Iron Intakes.” Journal of Nutrition 133 (11) (Suppl. 2): 4031S–26S.

Simran, D. and V. Tarasuk. 2019. “Race and Food Insecurity: Fact Sheet.” Research to PROOF Food Insecurity Policy Research and FoodShare.

Spade, D. 2020. “Solidarity Not Charity: Mutual Aid for Mobilization and Survival.” Social Text 142 (1): 131-151.

Statistics Canada. “Food Insecurity During the COVID-19 Pandemic, May 2020.” June 24, 2020.

Tarasuk, V. 2017. “Implications of a Basic Income Guarantee for Household Food Insecurity. Research Paper 24.” Thunder Bay: Northern Policy Institute.

Tarasuk, V., A.-A. Fafard St-Germain, and R. Loopstra, R. 2020. “The relationship between food banks and food insecurity: Insights from Canada.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. 31, 841–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00092-w

Tarasuk, V. and A. Mitchell. 2020. “Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2017-2018.” PROOF Food Insecurity Policy Research.

Thompson, S., A. Gulrukh, M. Ballard, B. Beardy, D. Islam, V. Lozeznik, and K. Wong. 2011. “Is Community Economic Development Putting Health Food on the Table? Food Sovereignty in Northern Manitoba’s Aboriginal Communities.” The Journal of Aboriginal Economic Development 7 (2): 14–29.

Wakefield, S., J. Fleming, C. Klassen, and A. Skinner. 2012. “Sweet Charity, Revisited: Organizational Response to Food Insecurity in Hamilton and Toronto, Canada.” Critical Social Policy 33 (3): 427–450.

World Food Programme. 2020. “World Food Programme to Assist Largest Number of Hungry People Ever, as Coronavirus Devastates Poor Nations.” June, 29 2020.

- Koç et al. 2012, xiv. ↵

- World Food Programme, n.p. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Tarasuk & Mitchell 2020, 8. ↵

- Statistics Canada 2020, n.p. ↵

- Dhunna & Tarasuk 2019, n.p. ↵

- Health Canada 2006, 15. ↵

- Thompson et al. 2011, 24. ↵

- Tarasuk & Mitchell 2020, 10. ↵

- Wakefield et al. 2012. ↵

- Riches 1986, 22. ↵

- Food Banks Canada, 2020. ↵

- Tarasuk et al, 2020, n.p. ↵

- Tarasuk 2017. ↵

- Food Secure Canada 2012, n.p. ↵

- MacRae 2021, n.p. ↵

- Agriculture and Agri-food Canada 2021. ↵

- FoodShare 2020, n.p. ↵

- Plumwood 2007, 1. ↵

- See for example, Gibson-Graham 1996; 2006. ↵

- Ogle et al. 2001; Roos et al. 2003. ↵

- Big Door Brigade n.d., n.p. ↵

- See: Ocasio-Cortez. ↵

- Spade 2020, 131. ↵

the process of eliminating oppression and inequity in food systems; note that there are multiple definitions of food justice, depending on context.

a place where food—generally basic, non-perishable provisions such as rice, pasta and canned goods—can be accessed by those experiencing food insecurity.

the condition that exists when one or more people are not able to gain access to food in sufficient quality and quantity, often due to lack of economic resources, in order to live a healthful and active life; note that there are multiple ways that food insecurity has been defined, depending on context.

a condition of very limited market competition dominated by a small number of firms.

a proposed geologic epoch characterized by significant human impact on the natural world.

a political framework developed by the international peasant organization, La Via Campesina, emphasizing the rights of peoples to determine their own food systems, including the production and consumption of food through methods that are environmentally, culturally, and socially sustainable.

the organisms and environment of a cultivated agricultural area.

the groups to which people belong, due to their position in history and society.